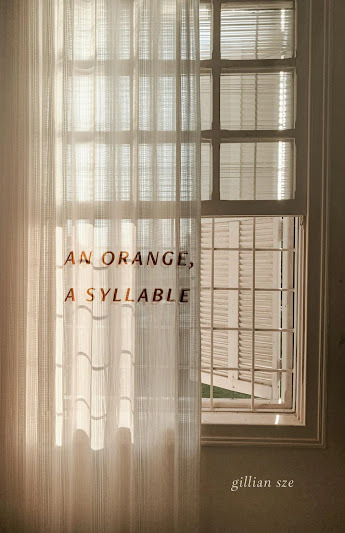

Gillian Sze, An Orange, A Syllable

My comparison of languageacquisition to some train, some countable linearity, is embarrassingly wrong. Babylanguage, I soon found out, was catachrestic. The child’s speech laid bareassociations and accidents. In the tub, she would point to the eye of the toywhale and say, Moon. She would clamber up the stepstool and say, Tree.And when the child pointed to the cracks in the floorboards, she would say, Hole,followed by, Ow. Point to the hole in my sock and say, Hole. Pointto the circles in the rug and say, Hole. Ow. All was lace. From thechild’s small mouth, she undid the world around me.

Havingbeen startled by how quietly good I thought her prior title,

quiet nightthink: poems & essays

(Toronto ON: ECW Press, 2022) [see my review of such here], I was intrigued to see Montreal poet Gillian Sze’s latest, thepoetry collection

An Orange, A Syllable

(ECW Press, 2025). As quietnight think: poems & essays was a blend of meditative, first person lyricprose and poems around the swirls and reconsiderations of self, culture andbeing that accompanied her new motherhood, this latest shifts those leaningsback into the shape and approach of the poem a bit further down Sze’s narrative/parentingline. This is very much a sequel to that prior collection, offering furtherinsights into culture, language, self and possibility through the ongoing lensof motherhood, partnership and domestic patter. “What were your words when thehome was at a standstill? My love / is limited. The last dish fell from a cupboard.At a talk about love, a / scholar spoke about agape. I never consideredthe ordered and clean / conditions of agape, the superior, transcendent, unconditionallove. I / did not know it.”

Havingbeen startled by how quietly good I thought her prior title,

quiet nightthink: poems & essays

(Toronto ON: ECW Press, 2022) [see my review of such here], I was intrigued to see Montreal poet Gillian Sze’s latest, thepoetry collection

An Orange, A Syllable

(ECW Press, 2025). As quietnight think: poems & essays was a blend of meditative, first person lyricprose and poems around the swirls and reconsiderations of self, culture andbeing that accompanied her new motherhood, this latest shifts those leaningsback into the shape and approach of the poem a bit further down Sze’s narrative/parentingline. This is very much a sequel to that prior collection, offering furtherinsights into culture, language, self and possibility through the ongoing lensof motherhood, partnership and domestic patter. “What were your words when thehome was at a standstill? My love / is limited. The last dish fell from a cupboard.At a talk about love, a / scholar spoke about agape. I never consideredthe ordered and clean / conditions of agape, the superior, transcendent, unconditionallove. I / did not know it.”An Orange, A Syllable is built as an accumulationof lyric prose blocks, seventy-six in sequence. Occasionally there might be asymbol set atop one of these blocks, as to suggest a new line of thinking, anew sequence or cluster, five in total across the collection. Throughout, Szewrites of love, of language and the new ways she’s learned to approach and encounter,both within and beyond a domestic space that almost sounds set within theCovid-19 era: “What is out there? I think I have forgotten. My world thicksdown / to the sweetness in each fold of laundry. The growing tower of cotton, /tidy and eversteady. For a while, I can stop thinking and let the hands /spread across the sleeves, the hems, the stitches. The hands know where / smoothnessis right, know where to put the parts and when the folds / are finished.” Again,as a furthering of her prior collection, Sze writes of engaging language, herown background and self in new ways, engaging with the immediacy, and thelayers one gains through attempting to communicate such to one’s children (withfamiliar echoes, certainly, of my own accumulation, through the book of smaller, of prose poems through and amid a similar period of domestic,parenting small children). To attempt to speak on any of this requires one’sown understanding, after all. This is a sharp and meaningful collection, andreason, once more, to go through that prior collection as well.

Dougong is an ancientChinese method of interlocking wood. Watchtowers and temples and dynasties havebeen built completely without bolts, screws, or nails. All the wooden parts—beams,brackets, pillars—fit with precise carpentry. A dialogue, too, is putting apicture together, closing all the gaps. When one speaks and the other replies,words snap together. Meanings are understood and there is a satisfying “click.”