12 or 20 (second series) questions with Danielle Vogel

Danielle Vogel is a poetand interdisciplinary artist working at the intersections of queer and feministecologies, somatics, and ceremony. She is the author of the hybrid poetrycollections

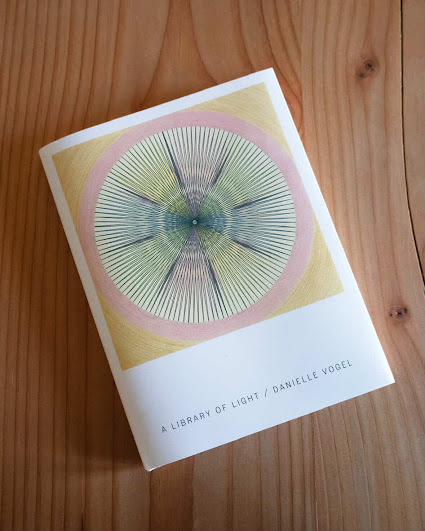

A Library of Light

(Wesleyan University Press2024),

Edges & Fray

(Wesleyan University Press 2020), The Way a Line Hallucinates Its Own Linearity (Red Hen Press 2020),and

Between Grammars

(Noemi Press 2015).Vogel’s installations and site responsive works have been displayed atRISD Museum, among other art venues, and adaptations of her work have beenperformed at such places as Carnegie Hall in New York and the TjarnarbíóTheater in Reykjavík, Iceland.

Danielle Vogel is a poetand interdisciplinary artist working at the intersections of queer and feministecologies, somatics, and ceremony. She is the author of the hybrid poetrycollections

A Library of Light

(Wesleyan University Press2024),

Edges & Fray

(Wesleyan University Press 2020), The Way a Line Hallucinates Its Own Linearity (Red Hen Press 2020),and

Between Grammars

(Noemi Press 2015).Vogel’s installations and site responsive works have been displayed atRISD Museum, among other art venues, and adaptations of her work have beenperformed at such places as Carnegie Hall in New York and the TjarnarbíóTheater in Reykjavík, Iceland.Vogel is committed to anembodied, ceremonial approach to poetics and relies heavily on field research,cross-disciplinary studies, inter-species collaborations, and archives of allkinds. Her installations and site-responsive works—or “ceremonies for language”—areoften extensions of her manuscripts and tend to the living archives of memoryshared between bodies, languages, and landscapes.

Born in Queens, New York, andraised on the South Shore of Long Island, Vogel earned a PhD in literature andcreative writing from the University of Denver and an MFA in creative writingand poetics from Naropa University. She is currently associate professorat Wesleyan University where she teaches workshops in experimental poetics,investigative and documentary poetics, ecopoetics, hybrid forms, memory andmemoir, the lyric essay, and composing across the arts.

Vogel lives in the ConnecticutRiver Valley with her partner, the writer and artist Renee Gladman, where shealso runs a private practice as an herbalist and flower essence practitioner.Learn more at: https://www.danielle-vogel.com/

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recentwork compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

When Carmen Giménez andNoemi Press picked up Between Grammars for publication back in 2015, after the initial immense joy andgratitude, I was flooded with an intense fear of being seen in a new way. I wasestranged from my family and felt that the published book-object would be a rawextension of my own form, a conduit through which they would have access to mein a way that filled me with a kind of terror. This fear became conflated with afear of the reader, a reader who might possibly not like the book.

When Between Grammars came out, I had to really ground myself in a newkind of poetics, one that included “the audience” in a way I hadn’t had toconsider before. I was no longer a poet without a book. And this book, BetweenGrammars, was a book about a book. About an author being met by areader through the unique and intimate ecosystem a physical book-object cancreate. I had to transmute that fear into intention. And this intention ispresent in each of my subsequent books: how can the book become a haven for myown story and the reader’s? This question is, in varying forms, at theroot of all of my collections.

A Library of Light, published nearly ten years later, is very directly about myfamily and maternal lineage, my motherline, as I say in the book. Thatfear, which grew from estrangement, that I mention above became a kind ofchapel I climbed inside of to write this book.

2 - How did you come to hybrid writing, as opposed to, say, a stricterdelineation of literary forms?

Honestly? Through the linernotes on a Bob Dylan album called, Desire. When I was 19 or 20, I pickedup this album from some hole-in-the-wall record shop in Manhattan. On theinside sleeve, the envelope that holds the LP, is a lyric essay, “Songs ofRedemption,” about the album written by Allen Ginsberg. Ginsberg’s signaturesays:

Allen Ginsberg

Co-Director

Jack Kerouac

School

of Disembodied

Poetics,

Naropa Institute

York Harbor, Maine

10 November

1975

I was like, hmmm, I know and love Ginsberg’s work and I’m totallydisembodied and I’m sort of a poet, what the heck is Naropa Institute? Itwas the early days of the internet, so I was able to find Naropa’s website,which was, by then, a university in a state (Colorado) I had never in my younglife considered moving to or even visiting. I knew I needed to leave home if Iwas going to survive my life. I requested an application, applied (in fiction),was accepted, settled in Boulder, and within a few weeks had met the phenomenalAnne Waldman and felt safe enough to come out as a lesbian. It was at Naropathat I was introduced to hybrid writing, book arts, and where I met and studiedwith writers like Akilah Oliver, Cecilia Vicuña, and Mei-mei Berssenbrugge,among endless other luminaries of hybrid and experimental forms.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Doesyour writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first draftsappear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out ofcopious notes?

I work like a birdbuilding her nest. But instead of that nest being built fairly quickly, as thebird must lay her eggs, my nests often take around a decade to be plaited intotheir final and sustainable forms.

4 - Where does a poem or hybrid text usually begin for you? Are you anauthor of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are youworking on a "book" from the very beginning?

Each of my texts begin with a question glowingat its center. If tended, this question acts as guiding and organizing force. Inever want to answer this question, only live with it devotionally letting mydays and manuscripts be sculpted by the ceremony. Because I think of the bookas a ceremonial container, a place within which a kind of transformation cantake place, I am always working on “a book” or “a ceremony” from the verybeginning.

I tend to write book-length poems or hybridmeditations. Often these are composed of a series of longer pieces. Althoughright now, I’m working on brief “veils,” “visions” and “drifts” in two of mymanuscripts-in-process. I let the project shape itself through the ceremony ofongoing attention.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Areyou the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I would say publicreadings are neither a part of nor counter to my creative process. But because,ideally, the book-as-intimate-object is central to all of my collections, Ioften wonder what is lost (or activated) when I become, in a way, the bookembodied or the object at a remove, not in the hands and minds andbreathing bodies of my readers.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kindsof questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even thinkthe current questions are?

Oh, yes. As mentionedabove, each of my books has a question glowing at its center. Some of myearlier questions were: What is language’s relationship withtrauma and embodiment? (for TheWay a Line Hallucinates Its Own Linearity) What is my responsibilityas a weaver of books, of habitations, for the bodies of others? (for Edges &Fray) If light had a translatable syntax, what would it be? (forA Library of Light) While those will always resound through my writing, oneof the questions I am holding close now is: What happens when we returnlanguage to Land, when we invite Earth into our bodies, when we remember thatlanguage weaves us (by way of breath, light, and consciousness) with others,with place?

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in largerculture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer shouldbe?

To remember. To weave. Ina time when many are hopelessly and infuriatingly watching the devastatinglive-streaming of multiple genocides, particularly of the Palestinian people,their homeland and ecosystems, it is more important than ever that we find waysto remember. What needs to be remembered is a very individual question.But that we, as artists, find ways to remember our shared humanity, ourconnection with lineage, place, language, one another, especially acrossdistances and differences, feels vital.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficultor essential (or both)?

I love the editor/authorrelationship and have been blessed by working with Suzanna Tamminen of Wesleyan University Press for my last two collections. She understands my work on acellular level and her editorial advice, instead of being line-based orstructural, is often what I think of as essential energy based. It’s asif she’s reading the vibrational field of my collections. She gives me thatlevel of editorial advice, which has been essential to my editorial rituals atboth macro and micro levels.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily givento you directly)?

Give your body whatit needs. Told to me very recently by the brilliant poet and astrologerSara Renee Marshall. I needed that reminder, especially in this time ofpolitical overwhelm where the powers that be are trying to flood and disorientus. As an herbalist and professor/mentor, I’m always helping others findbalance and nourishment in how they tend to their creative projects and living.I can forget to turn that care and attention toward myself.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (hybrid writingto installation)? What do you see as the appeal?

My practice has alwaystaken place both on and off the page. It is what my manuscripts and theirquestions necessitate of me. Each of my manuscripts have in-the-field companionprojects through which I explore the core concerns and mysteries of amanuscript. These are often ephemeral, durational, private, and site-responsiveworks. Because so much of my work, once published, has to do with my devotionto reintegrating a reader within their inner and outer environments, I seeinstallation or any of the work I do off the page as essential. My hope isalways to activate both inner and outer terrains, the visible and invisible,the conscious and subconscious, the known and unknowable and to bring them intosymbiosis. Right now, a lot of that work is made manifest through mycollaborations with plants and with/in herbals.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you evenhave one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

On a day when I don’thave to be on campus or go somewhere, I like to wake early. I press my herbalinfusion that I always set to steep overnight before heading up to bed, pour aglass, and sip it as a kind of morning prayer. Renee makes us a moka pot ofcoffee. Then I’ll light a candle and get to some kind of creative work for afew hours. Maybe I write. Edit photos. Blend client formulas. Then we oftenclose the morning’s work with a family hike in the woods. And then we come homeand cook a beautiful meal.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (forlack of a better word) inspiration?

Each of my manuscriptshas a journal or a series of journals within which I’ve traced the evolution ofits central question or intention. I think of these journals as living altarsfor the book. I always return to the beginning. Tend the altar. Relight thetaper of the earliest question. And see what rises in the glow of that renewedintimacy.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Shallots and garlicsauteing in a rich extra virgin olive oil. Wild roses. Sandalwood.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but arethere any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, scienceor visual art?

Oh, yes! I can’t helpbut think here of The Poetics of Space by Gaston Bachelard. Everythingfrom a cupboard to a nautilus shell to the contracting spiral of DNA to abird’s nest to a crystalline grain of pollen. In terms of A Library of Light,I held the drawings of Emma Kunz, Swiss healer and researcher, close over thedecade of writing. Epigenetic theory and the science of biophotonics were alsocentral avenues of research while I was writing the collection. I’m also anherbalist and flower essence practitioner and what I learn about poetry as ahealing modality through my ongoing collaborations with plants are at the rootof a lot of what I compose.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, orsimply your life outside of your work?

I mentioned some of themearlier, but the work and lives and devotions of writers like Cecilia Vicuña, Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, and M. NourbeSe Philip are incredibly important to me. I’m inawe of what their work, which feels inseparable from a kind of sacred practice,makes manifest. And then there are numerous brilliant friends who I write incommunity with like a. rawlings, fahima ife, Jen Bervin, Carolina Ebeid, Lucía Hinojosa Gaxiola (among many others!) and, of course, my love, Renee Gladman.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I would like to meetAntarctica.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be?Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you notbeen a writer?

Something in ecologicalrestoration. I’m very moved by the work of United Plant Savers and have oftenfantasized about joining them.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Writing is essential.It’s kept me alive.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

It was a while ago, butLauren Groff’s Matrix really still has a hold of me. I also can’t stopthinking about the film Petite Maman.

20 - What are you currently working on?

Iwork on many projects at once, but for the last couple of years I’ve beencollaborating with the multidisciplinary artist and director Samantha Shay, herSourceMaterial collective, and the Icelandic musician Sóley on a film project,which has my heart and attention this summer. As a part of that collaboration,I’ve been working on a manuscript tentatively titled Oracle Net, as wellas a lineage of flower and mineral essences that work with/in the text.