from the green notebook,

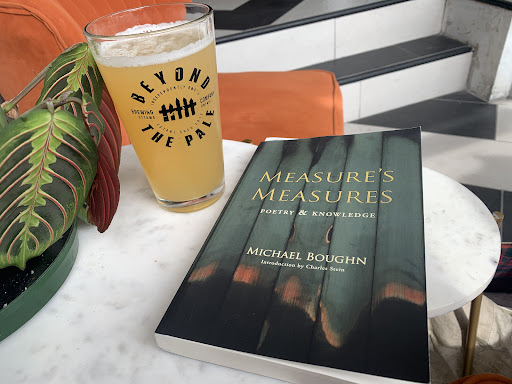

, reading Michael Boughn, Audrey Thomas, Maggie Nelson, Maggie Smith + Vladimir Nabokov

, further (spring 2024) notes from awork-in-progress,

[see multiple other sections from this project over at my substack]

Today is Aoife’s penultimate day of grade two. Rose finishedgrade five last week, and she is currently in Picton with Christine’s fatherand his wife, most likely in their pool as we speak. Christine is laid flatwith a cold, a trickling virus that has tendrilled through the house over thepast few days. It ignores Aoife, and Rose seems to have missed it, but I swatat the potential of impending summer cold with both hands. I will not get sick.

Reading through elements of MichaelBoughn’s new Measure’s Measures: Poetry & Knowledge (2024), I’mstruck by his descriptions of some of those “poetry wars” during and around theperiod of American poetry that developed The New American Poetry (1960).The term “poetry wars” has come up a bit again recently, in reference toconflicts in Prince George, British Columbia a decade or two back, as JeremyStewart and Donna Kane were putting together their folio of poetry and prose tocelebrate the life and work of Barry McKinnon (1944-2023) that I was postingonline at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics. Nothing any ofthe three of us wished to re-ignite.

I’ve never been interested inparticipating in wars. Ken Norris used to speak of poetry wars, some of whichhe got caught up with in the 1970s, with a kind of resigned inevitability. As Iunderstand them, most of these conflicts didn’t seem to stem beyond someonesaying something confrontational and others responding, or simply a matter ofdifferent aesthetics falling into the perceived requirement of a personalclash. What does it matter that one person writes a poem in a different way?There is work I am interested in and work I am less interested in; people I aminterested in and people I am less interested in. I think you’d be surprisedhow often those considerations blend into different configurations.

For the longest time, one of my absolutefavourite humans was Toronto writer Priscila Uppal (1974-2018), her early deatha devastating loss for everyone that knew her. A particular favourite spot ofhers in Ottawa was Zoe’s, the bar lounge of the Chateau Laurier, where we’dalways meet up when she came through town. She quite literally glowed withenergy, enthusiasm and creativity, and we were able to support and encourageeach other despite having little overlap, it seemed, in reading or writinginterest. Most of the writers and writing she admired and was influenced by Ihad little to no interest in, so how much could I really appreciate her work,no matter the quality?

There are numerous writers it would belovely to be able to sit down and have a beer with, and conversation; butsomehow, for some, aesthetics prevents us. There is so much that can be learnedfrom alternate perspectives on writing and thinking, and it becomes far tooeasy to fall into our bubbles. Is the goal not to expand our thinking? Is ourgoal not to improve, and make new? Why have a war?

*

Today is Aoife’s final day of grade two.Rose remains in Picton, for at least two more days. She is older, there.

I am moving slowly through final proofsfor these short stories, and thinking about how words get shaped on the page.Simultaneously, I am going through a recent reminiscence by Canadian writerAudrey Thomas on the late Alice Munro, sent out by email newsletter to membersof The Writers’ Union of Canada. Thomas writes of heading to do research inEngland in 1987, and convincing Munro, simultaneously aiming herself toScotland for the sake of her own research, to not fly to Scotland, but to joinThomas by boat. Thomas makes the trip sound delightful enough it almost makesme consider the same. Thomas writes of their sea-faring adventure, the two ofthem learning a handful of daily words in Polish, until a storm at the very endof the trip, upon entering the English Channel.

“I’m sorry it turned out tohave such a terrifying ending,” I said. “I wouldn’t have missed it for theworld,” said Alice.

*

Los Angeles writer Maggie Nelsonreferences Alice Munro as part of The Argonauts (2015). I had pulled thebook from yesterday’s shelves, opened it seemingly at random, and there it was:Munro’s work providing Nelson’s teenaged-self a perspective on sexualexperience, violation, lust “and how such ambivalences can live on in an adultsexual life.” The gift of clarity the greatest one can offer, after all.

I’ve been thinking of Nelson againrecently, having caught inklings via social media that she might have a newtitle either out or forthcoming, which made me curious. Naturally I haven’t yetset down to verify this. I’ve enough other reading in-progress I shouldprobably attend to, first. What of those essays on Sheila Heti and Lydia Davis?But I am curious.

This morning, reading through a recentpoem by Andy Weaver. He was good enough to comment upon my work-in-progresselegy for Barry McKinnon, “I wanted to say something,” so it just seems fairfor me to do the same for him. Sometimes one simply requires another eye.

“There’s a moral / here or there //isn’t,” he writes, as part of this sequence, “Cut,” “how a straight / edgecreates the curved // cut that will heal / in a crescent shape.” There hasalways been something quietly powerful about Weaver’s work, comparable to thework of Ottawa poet Jason Christie for their stretches of lyric concretenessacross lengthy meditative stretches, considerations of writing the complexitiesof fatherhood, the long form and their own modesty. I’ve been attempting to getthese two to interview each other for some time now, to clarify, perhaps, someof their overlap, but as of yet, I have been unsuccessful.

*

In a recent substack post, American poet Maggie Smith writes:

The writing life is one withmany paths. There’s no one way. I wish I’d thought more about this when I wasstarting out; it would have relieved a lot of pressure. And I wish I hadrealized how many writers—most of us!—have jobs outside of writing books. We’reteachers, editors, arts administrators, and technical writers. We’retherapists, receptionists, and childcare providers. We’re doctors, yogateachers, and small business owners.

When I say, “I’m a writer,” I’mtelling you about more than what I do for a living. I’m telling you who I am.

There’s a lot swirling around in those fewsentences worth commenting upon, at least from where I’m sitting: a variety ofresponses of what I might think, or have thought, or might say, or have said.Smith is entirely correct, obviously: as many ways to write as there might bepractitioners. As many grains of sand on the beach, say, or stars in theheavens. The first decade or so of my own foray into serious writing includedhaving to figure out how best to approach my own writing. It isn’t enough to learnhow to write, but learn how best I should be writing the things I should bewriting. There are no clear paths, nor across-the-board solutions. What mightwork for one might be anathema to another.

I work best through routine, and byscratching out attempts to figure out shape. My first drafts can often beleagues away from where the poem, the story, the manuscript, might finallysettle. Although, I say “settle” as though the process inevitable and smooth,of which it is neither; there are drafts upon drafts upon drafts, includingmultiple on paper and those through my own head. I used to take thirty to fiftyhandwritten drafts to make it to a single page, a single poem. Now the processis much more internalized, but my literary archive still grows in leaps andbounds, in pages scribbled upon and reworked. There is an endless array, evendown to the copy-edit. A word, moved. A word, excised. The occasional typo.

*

Someone posts a paragraph by VladimirNabokov to social media, on how he attempted to discern the difference of tastebetween a poisonous and non-poisonous butterfly. Why did he do this? And whathave we, as readers, learned through his experience?