Finding Pulp Fiction – Rafe McGregor

Last week I reviewed (and recommended) two of MarkValentine’s essay collections, Borderlands& Otherworlds and Sphinxes & Obelisks. Several of the essays in theformer, which was published by Tartarus Press in June, began as posts for Wormwoodiana, a fantasy,supernatural, and decadent literature blog he runs with Douglas A. Anderson (alsohighly recommended). A few of Mark’s recent posts have been about the changinglandscape of the second-hand book market, focusing on the perceived decline ofthe brick-and-mortar bookshop and the role of charity shops in eitheraccelerating or ameliorating that decline. In TheGolden Age of Second-Hand Bookshops (11 April), he argues that there hasbeen no such decline and that we are in fact in the middle of a Golden Age of second-handbook shopping, even if one discounts (no pun intended) charity shops that havesizable book sections. I should say straightaway that Mark has a great deal ofexpertise in the subject, the product of not only decades of finding books inunusual places, writing about forgotten books that deserve to be remembered,and writing about forgotten books found in unusual places, but also contributingto The Book Guide, whichis (I believe) the UK’s most reliable and most up to date directory ofbrick-and-mortar second-hand bookshops. I also agree with Mark’s claim that therise of charityshop bookselling has neither caused nor contributed to the perceiveddecline of the second-hand bookshop. What I am not so sure about is whether this is a Golden Age for book collectors – that has certainly not been my experience.Let me explain.

For a decade and a half one of my great pleasureswas browsing the shelves of chain, independent, and second-hand bookshops…then oneday I realised I’d stopped and had no desire to return to the pastime, in spiteof highlights such as: Waterstones (Glasgow), Leakey’s (Inverness), Murder One(London), what I think might have been Alan Moore’s basement (Northampton), StMary’s (Stamford), Foyles (London), Blackwell’s (Oxford), Richard Booth’s(Hay-on-Wye), Bookbarn (Midsomer Norton, in Somerset), Borders (York), BarterBooks (Alnwick), and Broadhurst (Southport). The reason I stopped frequenting bookshopswas no doubt a combination of multiple factors, some of which were: a belatedcompetence with both Amazon and ABE; an increased amount of reading and writingat my day job, which was wonderful but meant that I shifted most of reading forpleasure to audiobooks; and perhaps just being spoilt for choice – my wife andI lived in York for much of this time, which had the highest concentration ofbookshops in England outside of London (or at least the highest within easywalking distance of one another). After a hiatus of about another decade, forreasons that were probably also related to life changes, I slowly picked upwhere I’d left off, beginning with Hay-on-Wye and moving on to London and then backto York.

In York, the magnificent (and labyrinthine) Borders on ParliamentStreet was long gone (having closed several years before we left) and so wereat least two each in Walmgate and Micklegate. Thisproved to be a repeat of my experience in Hay-on-Wye, which had thirty-three bookshopswhen I last visited (the interval was about two decades) and now has twenty-five.The same is also true of Charing Cross Road and Stamford (in Lincolnshire),which both have significantly less bookshops (of all varieties) now than theydid a decade or more ago. From my list of favourites, Murder One, Bookbarn, andBroadhursts have all closed. It may not be book Armageddon, but every place I’veassociated with a plethora of bookshops seems to have fewer than before. Markattributes the widespread failure to acknowledge the present as a Golden Age tonostalgia, to mostly middle-aged people remembering their early book browsingdays with a fondness that has more to do with its circumstances (typically,being at university or exploring new places with friends instead of family forthe first time) than the actual number of bookshops. I take his point, but itdoesn’t apply in my case as my book browsing only began in earnest in my latetwenties, a period for which I have no nostalgia whatsoever. Which is why I haveyet to be completely convinced.

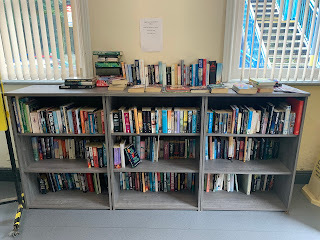

Perhaps neither Mark nor I are in error and it’s acase of more second-hand bookshops overall, but more widely spread with fewer and/orsmaller clusters like those I mentioned. Mark also draws attention to the widervariety of book vendors – beyond second-hand and charity shops – as part ofthe Golden Age, which brought my local train station to mind. For the last fewyears (since the end of the pandemic, if I remember correctly), the ticketoffice has boasted a mini-library of about two hundred and fifty books(pictured top). They aren’t sold, but the idea is that you bring one and takeone and you’re free to keep the one you took as long as you replace it withsomething else…which makes it a source for the book collector as much as any of theothers Mark lists. I recently picked up a copy of Jim Butcher’s StormFront (2000), the first of his Dresden Files, which I’d been meaningto read for years. (I replaced it with another occult detective title, freshfrom Theaker’s Paperback Library.) Now this is a nostalgic experience becauseit reminds me of the first second-hand bookshop I ever patronised. The place wastiny and the science fiction titles so popular that the owner wouldn’t allowyou to buy one unless you brought one in to sell to her first. (And no, I’m notmaking that up.) The idea of a railway library seems to be relatively newbecause when I searched online, the only related result was in Hartlepool, wherea local author donated books to the station in February. In America,I’m reliably informed, some people have taken to doing the same in their gardens(pictured above). If that trend is ever imported, I might have to revisemy opinion on the Golden Age…