Meditations: The Assorted Prose of Barbara Guest, ed. Joseph Shafer

I’m so pleased to be hereand of course one of my difficulties in life is not just writing poetry; it’scollecting my particles and wondering what I’m supposed to do where, so I thoughttoday was going to be a discussion, of what the poem is about, so I brought apoem on Anne-Marie Albiach. About two weeks ago, at home, I was looking throughsome old diaries that of course weren’t completed but still had white pages andI saw at the top of one page—oh this was ten, fifteen years ago—“Wrote a letterto Prynne,” “Received book from Anne-Marie Albiach,” and, in little brackets, “Sheinspires me,” and now that I know her and know her work more, she inspires memore. So there was a birthday celebration for Anne-Marie in San Francisco and Iwrote a poem to her in celebration of this, of her, of her poetry, and after I’dfinished it, I realized that what I’d written about, because she is very muchon my horizon, that I’d written about the process of writing a poem. So I’mgoing to read this [poem, “Startling Maneuvers”] and we’re going to discuss it—Mei-mei’sgoing to tell you what it means… [laughter]. (“A Talk on ‘Startling Maneuvers’,”1998)

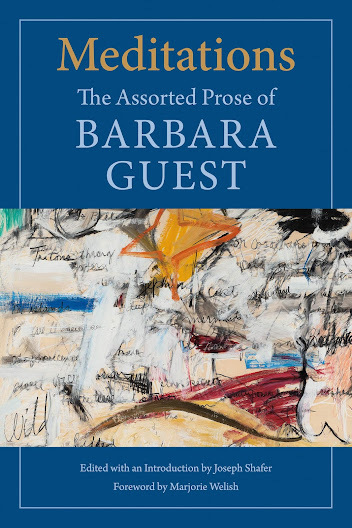

Thereis a lot to admire across the three hundred-plus pages of heft in

Meditations: The Assorted Prose of Barbara Guest

(Middletown CT: Wesleyan UniversityPress, 2025), edited with an introduction by Joseph Shafer and foreword byMarjorie Welish. Assorted, it is called, as it is neither collected norselected, a process of assemblage, “six decades of writing on literature andart by one of the most significant poets of our time,” the late Brooklyn poet Barbara Guest (1920-2006), a poet who first came to prominence as one of theNew York School. “Barbara Guest is a poet, first and foremost. And so, whenreading her writings otherwise, it is with this vocation in mind.” writes MarjorieWelish, to open her “Mysteriously Defining the Foreword.” “A celebrated NewYork School poet, Guest assumes that daily life, the intimacy of conversation,and friendship real or imagined are ever at hand. Presupposed also is thecultural life of the city: cafés, painters’ studios, bookshops—at least as NewYork was in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. But she sees all these as prompts forwriting through an imaginative style that invents worlds she knows are out ofreach as projected fantasies of another time and place, and yet worth thechallenge: the challenge to make of style a palpably lived atmosphere.”

Thereis a lot to admire across the three hundred-plus pages of heft in

Meditations: The Assorted Prose of Barbara Guest

(Middletown CT: Wesleyan UniversityPress, 2025), edited with an introduction by Joseph Shafer and foreword byMarjorie Welish. Assorted, it is called, as it is neither collected norselected, a process of assemblage, “six decades of writing on literature andart by one of the most significant poets of our time,” the late Brooklyn poet Barbara Guest (1920-2006), a poet who first came to prominence as one of theNew York School. “Barbara Guest is a poet, first and foremost. And so, whenreading her writings otherwise, it is with this vocation in mind.” writes MarjorieWelish, to open her “Mysteriously Defining the Foreword.” “A celebrated NewYork School poet, Guest assumes that daily life, the intimacy of conversation,and friendship real or imagined are ever at hand. Presupposed also is thecultural life of the city: cafés, painters’ studios, bookshops—at least as NewYork was in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. But she sees all these as prompts forwriting through an imaginative style that invents worlds she knows are out ofreach as projected fantasies of another time and place, and yet worth thechallenge: the challenge to make of style a palpably lived atmosphere.”Thebook is assembled into thematic sections—“LECTURES, ESSAYS, & POETICPIECES,” “PROFILES,” “H.D.,” “OTHER FICTION” and “REVIEWS”—the breadth of suchshowcase a writer and thinker deep in the trenches of artistic engagement. Shewrites on her own practice, and the work of numerous writers and artists surroundingher, including Frank O’Hara, Charles Olson, Richard Tuttle, Helen Frankenthaler,Piet Mondrian, Anne Waldman, Kenneth Koch, Dennis Phillips, Robert de Niro (Sr.),Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, Harry Mathews, Anna Balakian, James Schuyler, LouiseBourgeois, Robert Duncan and numerous others. Her work displays a curious mind,one deep in the thick of it. As Guest quotes from Plato in her piece “Forces ofImagination,” cited as a “talk delivered in April 1999 at Guest’s award ceremonyfor the Robert Frost Medal for Lifetime Achievement in Poetry by the PoetrySociety of America”: “If any poet were to come to us and show his art we shouldkneel down before him as a rare and holy and delightful being, but we shouldnot permit him to stay. We should anoint him with myrrh and set a garland of woolupon his head and send him away to another city.”

I’mstruck by numerous lines throughout this collection, including her openingcommentary on a poem by French poet and translator Anne-Marie Albiach(1937-2012), the opening paragraph of that particular lecture I quote above, atthe offset of this particular review. Further along in the same piece, respondingdirectly to that particular poem by Albiach, Guest offers: “My interpretationof this is that when you come to the point in a sensibility when you’reapproaching a poem, that is the preparation, and there is always a stasis,which contains balance and then non-movement. You are prepared to move but you’restill balancing yourself. And the pull in the composition, which is physical becauseit has to announce itself and it announces its frailty, its physical presence,and that’s why its tug is phantom-like. And it’s beginning to have its phantom-shadowon the poem. And this pull is so extraordinarily important because if you don’tfeel the pull between the poem and you, then you somehow or other don’t manageto produce anything that has much energy.”

Asmost books of this nature, this scale, have worthy stories to tell of how theycame to be, this particular project’s timeline is a bit longer than most, as editorJoseph Shafer writes to open his introduction:

In the summer of 2004,Barbara Guest signed two contracts with Suzanna Tamminen, the editor atWesleyan University Press. One was for a collected poems and the other for acollected prose. The projects were actually proposed together five yearsearlier in 1999, after Wesleyan published Guest’s Rocks on a Platter: Noteson Literature, a turn-of-the-century quasi-manifesto in the spirit of StéphaneMallarmé’s Un coup de dés. But several years went by between that initialproposal and the eventual signing because Guest and Tamminen were busy publishingMiniatures and Other Poems (2002). Once those contracts were filed,conversations about what either a collected prose or poems would entail had tobe postponed as their attention was directed back toward the release of TheRed Gaze (2005). Thus, when Guest passed away on February 15, 2006, neithera collected poems nor a collected prose had taken shape.

I’lladmit, I’ve been aware of Guest’s work for some time, but have only takencursory glances at The Collected Poems of Barbara Guest (Wesleyan, 2013),a project begun while the author was still alive, but completed by herdaughter, Hadley Baden-Guest, for the sake of publication. A collection such asMeditations, offering her conversation and thinking on writing andvisual art, I would argue, makes for a remarkable entry point to her work, onerife with stellar lines and numerous prompts into other directions. Her work onH.D. (1886-1961) alone is intriguing, and would make for an interestingcounterpoint to the extensive work by Robert Duncan (1991-1988) [discussed at length by Toronto poet and critic Michael Boughn through his own essays, which I reviewed here], which she references as well, within her pieces assembled here.“Since the completion and publication of my biography of H.D.,” she writes, toopen “The Intimacy of Biography,” “I now realize that I have been seeking thatspecial state of grace I had experienced while writing this book, and this hasdeparted with the disappearance of H.D. and her companions from my immediatelife. I reach out in search of that powerful light, or that sombre candle thatlit the landscape of my own life as I struggled through the successive vales ofa heretofore uncharted realm.”

Separately,I’ve heard talk of Norma Cole co-editing a forthcoming new volume of collectedor selected poems of Guest’s poems, which is intriguing, given the fact thatthe prior volume assembled all of Guest’s published work. It makes me curiousat the framing, the argument, of this upcoming collection. Will it include workpreviously uncollected, unpublished or otherwise unseen? Or will it focus moreon certain aspects of her larger publishing history, certain collections, witha refreshed or expanded framing? Either way, I am intrigued.