A Load Of Golf Balls

G K Chesterton called it “an expensive way to play marbles” but in 2024, according to a survey conducted by Our Sporting Life, more than one in twenty of those aged 16 or over in the UK planned to indulge at least once a month. Men were three times more likely than women to play at least once a month while those most likely to pack a bag of clubs and a box of balls into the car are aged between 25 and 34.

In essence, golf requires a combination of skill, strength, and accuracy to hit a ball over several hundred yards and finish by sinking it into a hole 4.25 inches in diameter. Counterintuitively, it is one of the few sports where the worse you are, the longer the game lasts. One of the least considered components of a golfer’s equipment, the ball itself, has a fascinating history of its own involving technological advances and a developing understanding of aerodynamics.

While the original balls might have been wooden, the point is as highly controversial as the evidence is slight, by the start of the 16th century the Scottish pioneers were using a hand-sewn round leather ball filled with cow’s hair or straw, imported from the Netherlands. By the middle of the century, though, these balls, known as “hairy balls” were being manufactured by the “cordiners or gouff ball makers of North Leith”.

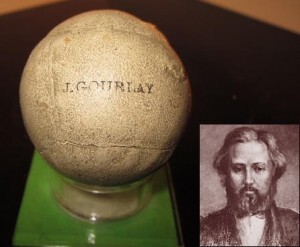

The next step forward came in 1618 with the introduction of the “featherie” golf ball which was stuffed with goose or chicken feathers rather than hair. The feathers and leather would be shaped when wet and allowed to dry. When the ball dried, the leather would shrink and the feathers expand, creating a hard ball. It would then be painted and the ball-maker would add their mark.

While the ”featherie” was harder and could fly further than the “hairy”, it was difficult to make them perfectly round, they had a tendency to lose distance when wet, and often split open upon impact. It was also an extremely time-consuming process to produce them, something reflected in the comparative costs of the two types of balls and they co-existed for some time, the “hairy” becoming known as the “common ball”.

Historians call 1848 the year of revolutions and it certainly was in the world of golf balls with the development of the Gutta-Percha ball or Guttie by Dr Robert Paterson. It used the dried sap of the Malaysian Sapodilla tree which had a rubber-like quality and, when heated, could be formed into a sphere. They were cheaper to make than the featherie and could be repaired if damaged, although golfers soon realized that the marks left on a guttie when struck by a club actually improved its aerodynamic properties.

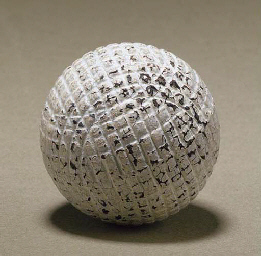

Manufacturers began to eschew smooth surfaces and intentionally indented their balls to attain better and more consistent flight. By 1890 gutties were being produced from moulds, improving their consistency and bringing down their price. A common mould pattern was the bramble, whose raised spherical bumps along the surface resembled the fruit of a bramble.

In 1898 Coburn Haskell, while whiling a few moments, wound some rubber thread into a ball and bounced it. Impressed by the degree of bounce it had, he put a cover over it and the rubber Haskell golf ball was born. Initially deploying the bramble pattern like guttie balls, they had a thin outer shell made of balata sap which covered a liquid-filled or solid core, around which was wound a layer of rubber thread.