RISKING IT ALL FOR AN ENEMY OFFICER

Do you think it was crazy to risk four crew members, two passengers and a perfectly good aircraft and fly into a HOT LZ in an attempt to save a wounded enemy’s life. This pilot did, and this is his story:

By Robert B. Robeson, LTC, USA (Retired)

“If a man hasn’t discovered something that he will die for, he isn’t fit to live.”–Martin Luther King Jr.

It was Sunday, March 7, 1970, at our 236th Medical Detachment (Helicopter Ambulance) headquarters at Red Beach in Da Nang, South Vietnam where my flight crew of four was on 24-hour standby duty. I’d recently been promoted to unit commander as a captain the previous month. Combat action had been quiet that morning in our area of operation and no medevac missions had yet been received.

After returning from chapel service, a half-block away in The Viking compound, I’d had lunch and then returned to my hootch across from operations to get out of the blazing sun. At about 1:00 p.m., Gunter Stiller, a West German chief reporter for the Bild am Sonntag Berlin newspaper was driven up to our operations building by a U.S. Marine bodyguard in a Jeep, along with the newspaper’s German photographer.

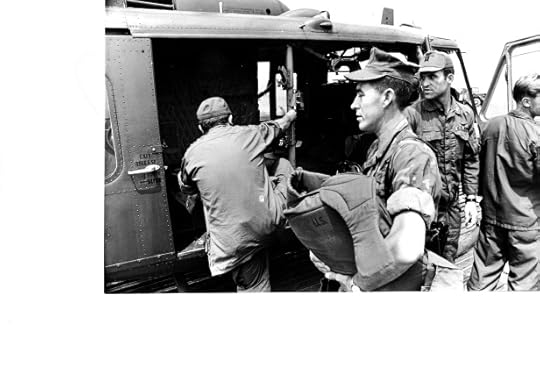

Bild am Sonntag Chief Reporter Gunter Stiller climbs into the “hell hole” on right side of the Huey’s jet engine, while his Marine bodyguard is directed to the left side “hell hole,” by Captain Robeson. Flight medic, SP5 Tom Franks, gets ready to close pilot’s door.

Stiller introduced himself and said he had permission and a recommendation from both U.S. and Vietnamese authorities to do a story on our unit because of the heavy action we’d been involved with in the past few months. He asked for permission to accompany us should a mission be called in during the following few hours. I told him that if we did receive one, his request to accompany us would depend on how many patients we’d have to evacuate, since three additional bodies might create a weight dilemma with a full load of fuel in high heat conditions. I also informed him that I had no problem if the three of them wanted to risk their lives along with us.

Then, in an effort to be frank and forthright, I mentioned that I’d had seven aircraft shot up by enemy fire and had been shot down twice in my first eight months in-country, which included around 850 medevac missions for over 2,200 patients. I emphasized that in our line of work, in a dangerous and bloody combat environment, our flight crews always had the opportunity to make a name for ourselves…postumously. Stiller, short and nearly bald, confirmed that he still wanted to fly with us and began interviewing me, taking notes and asking questions about our mission, unit personnel and how many patients we’d evacuated.

About a half-hour later, our operations specialist knocked on my hootch door to inform me that an infantry full-colonel wanted to talk to me on our landline phone. As Stiller listened to my side of the conversation, and his photographer was busy taking pictures, this colonel explained that an infantry company was in heavy contact with what was believed to be a North Vietnamese Army (NVA) battalion-sized force sixty kilometers northwest of Da Nang. He said these U.S. troops were surrounded in a remote V-shaped valley in dense jungle. During the fighting our soldiers had seriously wounded and captured an enemy officer.

“Captain,” the colonel said, “I’m told the landing zone (lz) is insecure and really tight, they’re taking a lot of small arms fire, but this guy isn’t going to make it unless you can get to him in a hurry. Having to guard him and deal with his wounds is compounding the problems our guys are having in continuing to fight in their outnumbered position. And you’ll probably need to take along a hoist because they say there may not be enough room to land.”

Since the safety of the lz couldn’t be guaranteed by our ground force, and the patient was an enemy soldier, we both understood (though it was left unstated) that no one could order me to fly the mission. As aircraft commander, it would be my call alone. If I agreed to go, I’d have to risk seven souls: our four crew members, three passengers, plus an expensive and critical aircraft. Although I’d always had a stubborn desire for living longer, I told the colonel we’d do our best to evacuate this officer.

That’s when my biblical upbringing in the home of a Protestant minister caused me to reflect on what caring for others meant regarding his teaching and fatherly guidance as I grew up. My role in Vietnam combat was ultimately attempting to save as many lives as possible, even when it involved a wounded foe. The fact that North Vietnam had never signed the Geneva Convention Rules of War agreement, as the U.S. had, it was still my responsibility as a medevac pilot and unit commander to ensure any prisoner of war received humane treatment and medical care to the best of my ability. Other military branches, such as the Marines, Special Forces, infantry and artillery personnel, had different roles to fulfill that required them to seek, find and finish the enemy in a kill or be killed scenario. Our mission was supposedly to be as “noncombatants.”

We flew unarmed helicopters. If a landing zone was considered insecure we’d request gunship cover in an attempt to protect both us and our patients. Sometimes they weren’t available and we’d have to go in alone by ourselves. And often having gunships along wasn’t always enough to keep us from being shot up or shot down. Since the other side wasn’t bound by the same international warfare restrictions as we were, it was mostly open season on medevac aircraft and personnel. The large red crosses on our birds could often turn into major targets and aiming points if the enemy so chose…and they chose a lot. That’s why so many of our evacuation missions were reminiscent of the Wild West on steroids. Taking ground fire and confronting death in close combat on a daily basis, for our flight crews and patients, was as common as a pencil point breaking. Our unit personnel still acknowledged, among ourselves, that “grunts” on the ground had it the toughest of all due to how they were forced to live and endure “humping the boonies,” day after weary day, in every kind of weather, terrain and environmental circumstances imaginable.

As our crew and three potential passengers were driven, in a 3/4-ton truck, down to our flight line above the beach on the southern shore of Da Nang Harbor, I thought about our potential patient lying out in the jungle in a life-threatening situation. Although he undoubtedly had loved ones up north who cared whether he lived or died I had to admit, at that precise moment, that I felt he had less in common with me than almost anyone else in the world.

While the rest of my crew got the aircraft ready for flight, I directed our passengers to one side for a quick briefing.

“Listen,” I began, “I want you to be aware about what’s going on out there and that our troops on the ground are surrounded by a much larger ‘bad guy’ force. There’s always the possibility that we could be shot up or shot down. The colonel said this is supposed to be a jungle-covered V-shaped valley we’ll have to go down into that won’t give us much maneuvering room. If we run into trouble, and find ourselves down in that kind of terrain, there’ll be no idea of how long it might be before help arrives,” I added, emphatically. “And if we’re forced to use a hoist to get this guy out, we’re going to be exposed to whoever is out there while hovering 100-150 feet in the air for five or more minutes, like some dangling target in a shooting gallery. Just so you understand.”

That’s when Stiller’s photographer handed Gunter one of his cameras. Apparently risking his life along with us wasn’t any longer one of his main priorities after my truth session.

“Let’s go,” Stiller said, hanging the camera around his neck and heading for our aircraft. “Where do you want my Marine friend and I to sit?”

I told them they needed to take seats in the “hell holes” on each side of our UH-1H “Huey,” jet engine compartment. There wasn’t time to explain how these two canvas seats facing outward got their names. I’d already provided enough negative possibilities for them to contemplate.

As we climbed to altitude over Hai Van Pass north of the harbor, I said my usual silent prayer for our safety, for the grunts on the ground…and even for my enemy counterpart. I didn’t want to risk our lives and aircraft for a dead man. If he lived, he’d be my responsibility until we could deposit him at the Special Forces Hospital in Da Nang. That was based on the premise we weren’t going to get ourselves “hosed-down” or blown away in the process.

Two “Black Cat,” AH-1G “Cobra,” helicopter gunships, that were stationed on the east side of Da Nang at Marble Mountain Airfield along China Beach and the South China Sea, caught up with us en route. Our operation specialist had called them to cover us. My copilot coordinated with them and the infantry radio-telephone operator (RTO) at the pickup site over our FM radio. When we finally arrived over the deep and steep V-shaped valley, I realized that both fighting forces had chosen a lousy location to get into a brawl.

When we were about thirty seconds out from their eight-digit ground coordinate, our gunships asked the ground troops to “pop” a series of colored smoke so they’d know where all of our “friendlies” were located and where not to direct their fire. I’d already asked them to make one low-level pass using their mini-guns and rockets to let the enemy know these escorts would be taking names and packing plenty of firepower if they decided to interrupt and engage our patient extraction in progress.

CW2 Sandy Letcher (now deceased) provides last minute information to Captain Robert Robeson before liftoff to evacuate captured and seriously wounded NVA officer. CW2 Tim Yost is in the process of starting the helicopter.

After this initial gunship run, and once they’d swung around up the valley to get ready to lead us in, Tim asked the RTO to pop another smoke exactly where our patient was located and where they wanted us to land. It would also show us which way the wind was blowing. I’d been circling above the valley rim waiting for this final approach moment to begin.

Immediately, a cherry-red plume began to rise from a small clearing at the bottom of the valley. As I watched, it appeared that there was a short tree just off-center in this tiny lz. Tim identified the smoke’s color to the RTO, who confirmed it was correct, and I then radioed our gunships to request that they make their second gun run over the lz to draw attention away from us. I told them we’d be right on their tails. Then they could swing around and cover us again on our way up and out of the lz and valley.

Once again it was show time for our flight crew. The combat curtain was about to go up, or come down, for the final time before an enemy audience hostile toward the actors on stage, under less than desirable conditions.

When we were directly over the lz and red smoke, at 1,500 feet, I pulled the nose of our bird nearly straight up with my cyclic control stick, kicked the pedals out of trim, bottomed the collective control with my left hand, then dumped the nose into a dive. We fell out of the sky like one of those Acme safes Wile E. Coyote was always getting crushed by in his contentious interaction with the Road Runner in their TV cartoons.

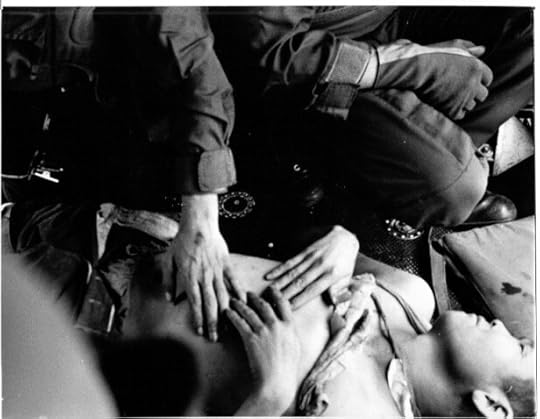

I began a series of evasive maneuvers hopefully designed to confuse any enemy watching in our rapid descent behind the Cobras. On the way down, I made the command decision not to use our hoist since I guessed I’d be able to squeeze our bird between that lone tree and the rest of the jungle. Fortunately, this time I was right. We received sporadic enemy fire going in and coming out, but didn’t take any “hits.” Our medic and crew chief quickly began to work on this officer who’d been shot in the back and one leg. We dropped him off at the Special Forces Hospital in Da Nang about 25 minutes later.

That’s when I experienced an exhilarating moment, a feeling of reverence, that I’d often felt after rescuing other patients from dangerous locations and situations.

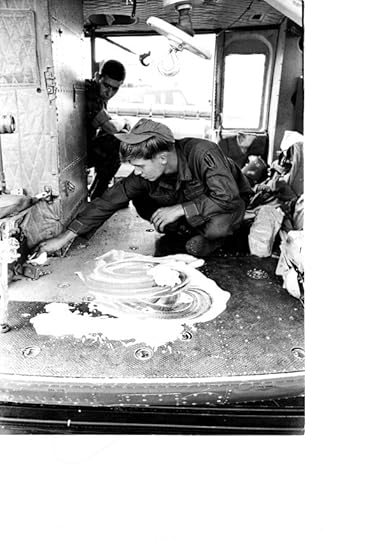

Captured and wounded NVA officer is placed on a litter at the Special Forces Hospital in Da Nang, South Vietnam.

I realized that this enemy’s desire to live was as strong as mine. His cries proved that he felt pain as intensely as I did. And the pool of drying blood that had accumulated beneath his body on our cargo deck was a reminder that it was the same color as mine. This awareness caused me to appreciate, once more, how precious a human life is…even an enemy’s. It was later relayed to us that this officer survived after undergoing emergency surgery.

There have been many moments of speculation in the past half-century when I’ve wondered if this officer survived the war. I often imagined him sitting in a hootch somewhere surrounded by his family while reliving many of his combat experiences. I visualized them clustered together as he recounted his memories of that medevac mission where his enemies, that he’d never met before and undoubtedly hated, had helped save his life. Perhaps he might have said, “You know, maybe our leaders in Hanoi were mistaken when they told us to hate all Americans because they were all bad. Why would some of them risk their lives to save mine while my own comrades were shooting at them and the helicopter that would fly me to a modern hospital for surgery that wasn’t available in the jungle? Maybe they all weren’t so bad after all.”

Captured North Vietnamese Army officer loaded aboard UH-1H Huey from remote jungle valley as flight medic, SP5 Tom Franks begins en route treatment of his wounds.

At the end of this Sunday afternoon in March 1970, that infantry colonel had gotten his valuable intelligence source (which I supposed was what he was most interested in from the beginning), our ground troops had gotten relief from their heavy burden of having to guard and initially care for this enemy officer, Gunter Stiller had gotten his unique newspaper story and photos, my crew had gotten our patient and our patient had gotten lifesaving medical care. It appeared to have been a profitable day for everyone involved.

There may be those who possibly think it was crazy to risk four crew members, two passengers and a perfectly good aircraft in an attempt to save one wounded enemy’s life. Since this mission was successful, I don’t believe it should be considered to be just another crazy medevac moment in a guerrilla war half-a-world away. I’m guessing that NVA officer would probably have agreed.

(From left to right) SP5 Tom Franks (flight medic), SP5 Dave Farnum (crew chief), unidentified Marine reporter bodyguard, Gunter Stiller (Chief Reporter for Bild am Sonntag newspaper), Captain Robert Robeson (aircraft commander), and CW2 Tim Yost (copilot), at Red Beach after the flight to evacuate captured and wounded NVA officer.

Postscript

I left South Vietnam, upon completion of my one-year combat tour, on July 10, 1970. After a 30-day leave, where I was reunited with my wife of 15 months, we left the U.S. for my next assignment with the 63rd Medical Detachment (Helicopter Ambulance) for four years in Landstuhl, West Germany.

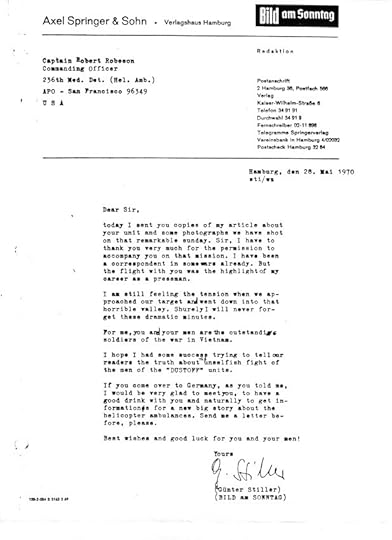

After settling in government housing on base, I wrote a letter to Gunter Stiller at Bild am Sonntag and informed him we’d arrived in Landstuhl and invited him to visit us for dinner, when he could, to reunite and reflect on that special mission. He’d already sent me a packet of 8″ x 10″ photos shot that day and copies of the three-page, 15 1/2″ x 11 1/2,” spread he’d written for his newspaper. He quickly accepted our invitation, we set a date and he drove all the way from Berlin to Landstuhl with his attractive, redheaded fiancee for dinner one evening. We reminisced for hours about what we’d experienced together on that mission. Sharing those unique and dangerous medevac moments together on another faraway continent is something I will always remember.

Letter to Captain Robert Robeson from Gunter Stiller a few months after this NVA officer mission:

This post was recently published online in Logbook Magazine

###

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video, or change occurs on this website—the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!