The Fall Of The Society For The Diffusion Of Useful Knowledge

Laudable as the aims of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (SDUK) may seem to us today, the prospect of an educated working class struck terror in the hearts of certain sectors of the upper classes. They envisaged the prospect of them getting ideas above their station and even challenging the social and political status quo.

Winthrop Mackworth Praed typified this attitude when he penned a piece for the verse the Morning Chronicle, published on July 19, 1825, lambasting the recently opened Birkbeck College and Mechanics’ Institutes for welcoming the lower classes. He wrote “but let them not babble of Greek to the rabble/ nor teach the mechanics their letters;/ The labouring classes were born to be asses,/ and not to be aping their betters”.

The SDUK became an easy target for the critics, not least because its principal movers, all Whigs, were already controversial public figures, none more so than Henry Brougham. He had earned the enmity of the King, George IV, when in 1820 in the House of Lords he successfully defended Queen Charlotte’s right to attend the coronation of her estranged husband.

Thomas Love Peacock took satirical aim at the impact of the SDUK’s educational campaign to better the servant class in Crotchet Castle (1831). In chapter two the Reverend Doctor Follett declares that he is “out of patience with this march of mind” because his cook “taking it into her head to study hydrostatics, in a sixpenny tract, published by the Steam Intellect Society”, falling asleep over it and knocking over a candle, setting the curtains light.

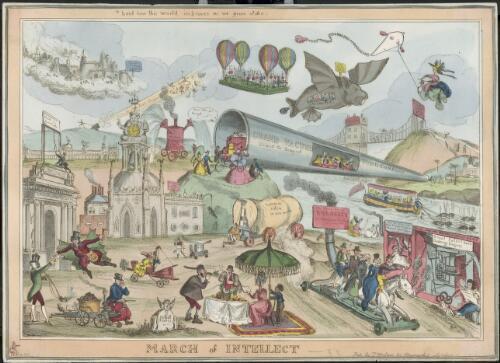

Brougham did indeed pen a pamphlet on hydrostatics, published as part of the Society’s Library of Useful Knowledge in 1827 and Peacock’s nickname for the SDUK, the Steam Intellect Society, associated the aim to spread knowledge amongst the population with the new technological advances such as the steam engine. This was a theme picked up by the caricaturists. Both George Cruikshank and William Heath produced several “March of Intellect” cartoons in which flying machines and other contraptions were displayed alongside a working man in rags reading a book.

The SDUK ploughed on but by the mid-1830s found itself in financial difficulties, having overstretched itself in establishing new publications and its subscribers reducing from 500 in 1828 to less than forty in 1843. It folded in 1846 but within the twenty years of its existence the country had seen significant social and political reforms which went some way towards improving the lot of the ordinary people.

The Society’s archives contain many letters from grateful readers and sales figures suggesting that its pamphlets and journal were widely read. It certainly had played a part in 19th century Britain’s educational history and made an indelible mark on many.