GREEN PIGS THROUGH THE LOOKING-GLASS - MUSING ON THE MOME RATHS AND OTHER CARROLLIAN CREATURES.

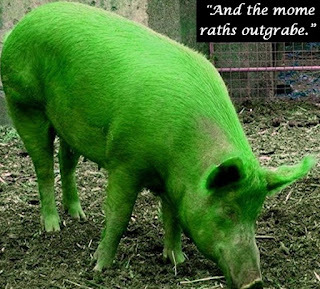

InLewis Carroll's Looking-Glass Land, mome raths are small green pigs with longsnouts (© Dr Karl Shuker)

InLewis Carroll's Looking-Glass Land, mome raths are small green pigs with longsnouts (© Dr Karl Shuker)Down through the years, I've documentedhere on ShukerNature, and subsequently in various of my books, a number ofmysterious creatures featured in certain famous works of literary fiction,investigating their possible origins, in particular the real-life animals thatmay have inspired their creation.

Such book-dwelling beasts chronicled byme include (but are by no means limited to): the Cheshire cat and the mockturtle from Lewis Carroll's classic children's book Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (click here and here to read my respective accounts ofthem); the tiny but deadly snakeling Karait from Rudyard Kipling's stand-aloneshort story 'Rikki-Tikki-Tavi' (click here); the rather larger but no lesslethal Indian swamp adder (aka the Speckled Band) and the giant rat of Sumatraconfronted by the great detective Sherlock Holmes (click here and here); the dream-like hound of thehedges from Charles G. Finney's celebrated fantasy novel The Circus of Dr Lao (click here); the wild were-worms of the LastDesert as referred to by Bilbo Baggins in J.R.R. Tolkien's The Hobbit (click here); Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's huge Brazilianblack cat (click here); Ron Weasley's giant spidernemesis in a Harry Potter novel (click here); plus a veritable menagerie ofscientifically-unrecognised fauna, from a purple bird of paradise and giganticluna moths that really are from the moon to some shy living dinosaurs, a giantpink sea snail, and the incredible bicranial pushmi-pullyu, all inhabiting the delightfulDoctor Dolittle novels written by Hugh Lofting (click here, here,and here).

The1969 Bancroft Classics #47 hardback edition of Through the Looking-Glass that I owned as a child (© Bancroft Books– reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis foreducational/review purposes only)

The1969 Bancroft Classics #47 hardback edition of Through the Looking-Glass that I owned as a child (© Bancroft Books– reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis foreducational/review purposes only)

As it's been a quite while since I lastwrote about any such literary cryptids, however, I feel that it's high time Idid so again – and what better source to choose from than Lewis Carroll'ssecond Alice book, Through theLooking-Glass, and What Alice Found There (to give it its full title),which was published in 1871, six years after Alice's Adventures In Wonderland. As a child I enjoyed this sequelnovel even more than the original, afore-mentioned Alice book, because itsstoryline and characters were far less familiar to me.

In particular, I was fascinated by thepoem 'Jabberwocky', one of the world's best known nonsense poems. Aliceencounters it quite early in Through theLooking-Glass, but as it is written in mirror-image format, she initiallyfinds its verses difficult to read. Moreover, even when she is able to readtheir reflection in the titular looking-glass, she still cannot understand thembecause she discovers that they are packed with bizarre made-up words – wordsthat confused but captivated me just as much as they did with Alice, until sheencountered the nursery-rhyme character Humpty Dumpty, a self-proclaimedetymological expert, who explained many of them to her.

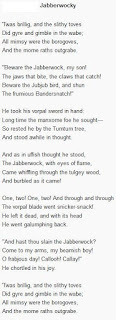

Thefull version of Lewis Carroll's self-penned nonsense poem 'Jabberwocky', asfeatured in his second Alice novel, Throughthe Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There – please click this poem'spicture here to enlarge it for reading purposes (public domain)

Thefull version of Lewis Carroll's self-penned nonsense poem 'Jabberwocky', asfeatured in his second Alice novel, Throughthe Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There – please click this poem'spicture here to enlarge it for reading purposes (public domain)

Moreover, the latent cryptozoologiststirring within me even as a youngster meant that I was additionally fascinatedby this poem's tantalizingly brief, ambiguous references to a number ofstrange-sounding beasts that seemed endemic to Looking-Glass Land – creatureslike the slithy toves, for instance, or the bandersnatch, the borogoves, themome raths, and, needles to say, the eponymous monster itself, the jabberwock.Some of these were succinctly described by Humpty Dumpty, but others were not,thereby remaining enigmatic and elusive. Consequently, down through the yearsmy childhood memories of this poem have inspired me to seek out furtherinformation concerning its fabulous if fictitious fauna in the hope ofdetermining what kinds of creatures they were – and here is what I've foundout.

As Humpty Dumpty explained to Alice, manyof those weird words in 'Jabberwocky' are portmanteaus, i.e. they have beenformed by combining two or more separate, well-known words together to yield atotally new albeit far less familiar one. 'Slithy', for instance, arises fromthe combination of 'slimy' and 'lithe', 'frumious' from 'fuming' and 'furious','mimsy' from 'flimsy' and 'miserable', 'chortled' from 'chuckled' and'snorted', and so forth (Humpty Dumpty elucidating most of these for Alice). Thenthere are some that are simply extrapolations from existing words, such as 'beamish',defined by Carroll as beaming radiantly with joy or happiness (though,interestingly, scholars have subsequently discovered that this is onepeculiar-sounding word in 'Jabberwocky' that Carroll did not invent, its usagehaving been traced back as far as 1530).

Achortling mome rath beneath a beamish moon!

Achortling mome rath beneath a beamish moon!

For the most part, however, such forms ofword derivation do not assist in revealing the respective natures of thevarious anomalous animals mentioned in 'Jabberwocky'. Consequently, it is fortunatethat between Humpty Dumpty's in-book revelations, the accompanyingillustrations prepared by Sir John Tenniel (who had previously prepared thosethat had illustrated the first Alice book), and various explanatory notes madeby Carroll in a publication that preceded Throughthe Looking-Glass's first printing by almost 20 years, much of the mysterysurrounding them can be dissipated.

The publication preceding Through the Looking-Glass was aperiodical entitled Mischmasch,written and illustrated by Carroll himself, which was published in 1855. It washere in which the original, significantly shorter version of 'Jabberwocky'first appeared, consisting of just the first verse of what would subsequently becomethe full multi-verse version in Throughthe Looking-Glass, published 16 years later. Needless to say, therefore, asthe jabberwock itself is not actually mentioned in the first verse, thatoriginal single-verse version was not titled 'Jabberwocky'. Instead, Carolldubbed it 'Stanza of Anglo-Saxon Poetry'. And as will be seen, it is veryintriguing how Carroll's concept of what some of his fictional creatures looklike changed quite dramatically from his descriptions of them in thisperiodical to his descriptions of them (as verbalized via Humpty Dumpty) in thenovel.

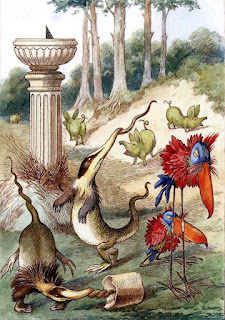

Avintage colorized version from 1927 of Tenniel's illustration depicting some ofthe cryptic creatures alluded to in Carroll's poem 'Jabberwocky' - the two badger-faced animals withcorkscrew-shaped muzzles and webbed feet are toves; the two long-legged birds(one of them is kneeling with legs bent) are borogoves; and the four smalllong-snouted pigs are mome raths (green in colour, according to Humpty Dumpty,hence tinted here accordingly), of which three are in the foreground above thetoves and borogoves, with the fourth one just visible in the background to theleft of the sundial) (public domain)

Avintage colorized version from 1927 of Tenniel's illustration depicting some ofthe cryptic creatures alluded to in Carroll's poem 'Jabberwocky' - the two badger-faced animals withcorkscrew-shaped muzzles and webbed feet are toves; the two long-legged birds(one of them is kneeling with legs bent) are borogoves; and the four smalllong-snouted pigs are mome raths (green in colour, according to Humpty Dumpty,hence tinted here accordingly), of which three are in the foreground above thetoves and borogoves, with the fourth one just visible in the background to theleft of the sundial) (public domain)

So let's begin our annotated checklist ofthe 'Jabberwocky' wildlife. The creatures first mentioned in it are the slithytoves, which as noted earlier are apparently slimy and lithe, and are thesubjects of the most detailed description of any creature name-checked in thepoem. According to Humpty Dumpty:

Toves are something likebadgers, they're something like lizards, and they're something likecorkscrews...Also they make their nests under sun-dials, also they live oncheese.

And that is still not all. For as notedin the poem, they "gyre and gimble in the wabe", which as defined byHumpty Dumpty means that they go round and round like a gyroscope, and boreholes like a gimlet. As for the wabe, he states that this is the grass plotaround a sundial (where the toves make their nests) and is so named because it"goes a long way before it, and a long way behind it".

Onlyin Looking-Glass Land – a green pig beneath a blue moon!

Onlyin Looking-Glass Land – a green pig beneath a blue moon!

Conversely, back in 1855 Carrolldescribed the toves quite differently in Mischmasch,stating that they were "a species of Badger [which] had smooth white hair,long hind legs, and short horns like a stag [and] lived chiefly on cheese".Moreover, rather than defining the wabe as the grass plot around a sundial, heclaimed that it was the side of a hill.

Moving on to the borogoves, they aredescribed merely as mimsy in the poem itself, which as we have seen earlierindicates that they are flimsy and miserable. However, Humpty Dumpty expandsupon this briefest of accounts by stating that a "borogove is a thinshabby-looking bird with its feathers sticking out all round, something like alive mop". Tenniel's picture illustrates them as vaguely stork-like, withvery long legs (one of them is kneeling, so its lengthy legs are largelyconcealed beneath its body). Conversely, again, in his Mischmasch periodical Carroll had described this species as: "Anextinct kind of Parrot. They had no wings, beaks turned up, and made theirnests under sun-dials: lived on veal". Interestingly, therefore, it wouldappear that when writing Through theLooking-Glass, Carroll transferred to the toves the distinctive habit ofmaking their nests under sundials that he had originally attributed in Mischmasch to the borogoves.

Youlookin' at me? Is this mome rath feeling rather wrathful?

Youlookin' at me? Is this mome rath feeling rather wrathful?

Now we come to my favourite members ofthe 'Jabberwocky' zoo (though you've probably already guessed that, by virtueof their pictorial preponderance in this blog article!). Namely, the momeraths. Humpty Dumpty merely describes them as "a sort of green pig",whereas in perhaps his single most dramatic change of identity for any animal referredto in this poem, Carroll stated in Mischmasch:

'Rath' is "a species ofland turtle. Head erect, mouth like a shark, the front forelegs curved out sothat the animal walked on its knees, smooth green body, lived on swallows andoysters.

Transforming from a green land turtle toa green pig in just 16 years is quite a metamorphosis, that's for sure! Havingsaid that, I personally consider a small long-snouted green pig to be a muchmore delightful concept than a shark-mouthed, knee-walking land turtle,green-coloured or otherwise. And speaking of long-snouted: Tenniel appears tohave been wholly responsible for giving that particular characteristic to thequartet of mome raths depicted by him, an example of artistic licence, perhaps,as it certainly does not feature in either of the verbal portraits quoted abovefor this porcine species.

Amome rathlet (or green piglet, if you prefer!) – how cute is that??

Amome rathlet (or green piglet, if you prefer!) – how cute is that??

Perhaps the most unexpected of allportrayals of the mome raths, however, appears in Walt Disney's classic 1951animated feature film Alice in Wonderland.One rather sad, downbeat scene features a tearful Alice having inadvertentlybecome lost in the dark, forbidding Tulgey Wood, home of the jabberwock (butnever seen in this movie version). Suddenly, a voice breaks the somberstillness, warning Alice somewhat peremptorily not to step on the mome raths.Shocked, she looks down, and there all around her are small entities resemblingflowers but walking on two tiny legs. These very atypical mome raths dulyassemble themselves in various shapes, culminating in a large arrow that pointsto the route leading out of Tulgey Wood, which a very thankful Alice swiftlyfollows. Although these floral mome raths are certainly endearing (albeitinexplicable!), I feel that some animated green pigs would have been moreappealing to this movie's viewers, as well as being far more in-keeping withits somewhat psychedelic visuals.

But now to the descriptive component ofthis creature's name – from where is the 'mome' in 'mome rath' derived? Here,for the first time, we find little (if any) satisfactory explanations. Even theetymological egomaniac that is Humpty Dumpty confesses to Alice that he isuncertain regarding the derivation of 'mome' – an admission indeed! – offeringonly this vaguely hopeful suggestion: "I think it's short for 'from home',meaning that they'd lost their way, you know". Rather like Little Bo Peep'ssheep, then? As for 'rath': whenever I read 'Jabberwocky' as a child, 'rath'always reminded me of the word 'rasher' – who knows, perhaps I was ontosomething!

Acouple of seriously strange mome raths!

Acouple of seriously strange mome raths!

And with regard to this poem's claim that"the mome raths outgrabe", Humpty Dumpty reveals that"'outgribing' is something between bellowing and whistling, with a kind ofsneeze in the middle" (with 'outgrabe' being the past tense of 'outgribe').So now we know!

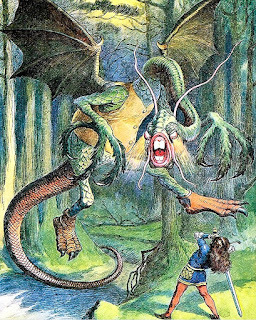

Moving now into the second verse of'Jabberwocky', it includes three more mystery beasts, the first, and also theforemost, of these being this poem's eponymous beast itself – the jabberwock. Yetin spite of its being the title character, very little descriptive informationis provided for this monster. It is said to have "jaws that bite" and"claws that catch", which apart from confirming that it does indeedpossess these particular anatomical accoutrements is of very little use,bearing in mind that their respective, exceedingly succinct one-verbdescriptions fit the activity of the jaws and claws of most animals thus equipped.

"Bewarethe Jabberwock, my son!"

"Bewarethe Jabberwock, my son!"

The only other details provided are the statementsin the fourth verse that the jabberwock has "eyes of flame", that it"came whiffling through the tulgey wood", and that it"burbled". The first statement is self-explanatory, and so, in asense, is "whiffling" – for instead of being a Carrollian invention,this is a real word whose usage can be traced back as far as 1568, and isdefined in the Merriam-Webster Dictionaryas emitting or producing a light whistling or puffing sound. As for"burbled", Carroll stated in a letter dating from 1877 (six yearsafter Through the Looking-Glass waspublished) that he didn't remember creating it, but surmised that it may be acomposite of 'bleat', 'murmur', and 'warble'. Interestingly, 'burble'subsequently entered the English language as an accepted word, and today isdefined in the Merriam-Webster Dictionaryas a verb that means to make a bubbling sound, and also to babble or prattle,plus a noun that means prattle. So, surprisingly, it looks like when ponderingthe origin of 'burble', Carroll didn't consider two words that seem much morelikely to have been bona fide components of it, namely 'bubble' and 'babble',than either 'bleat' or 'murmur' (though his third proposed component, 'warble',does still seems promising as a contender in this capacity).

Due to the scarcity of morphologicaldetails provided in thje poem, Tenniel was evidently given free rein whenpreparing his detailed full-page illustration of the jabberwock, which isreproduced in vintage colorized form below. As can be seen, Tenniel's terror isa most curious creature – combining a very lengthy elongate neck and tail, apair of insect-like antennae, and a pair of catfish-like mouth barbels withhuge bat-like wings, long bushy side-whiskers, and the incisors of a rabbit,plus, just for good monstrous measure, no doubt, it is wearing a very natty waistcoat!

Vintagecolorized version of Tenniel's original illustration of the jabberwock, from Through the Looking-Glass (publicdomain)

Vintagecolorized version of Tenniel's original illustration of the jabberwock, from Through the Looking-Glass (publicdomain)

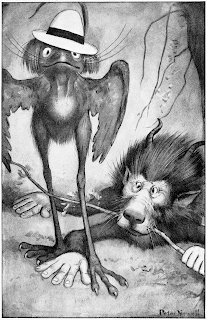

The other two mystery beasts name-checkedin the second verse are the jubjub bird and the frumious bandersnatch. Nodetails whatsoever are given in it regarding the jubjub bird, but as the fatherin the poem tells his son to beware both of these entities, we must assume thatthey were dangerous ones. The only additional clue regarding the bandersnatchis Carroll's use of the portmanteau adjective 'frumious' to describe it. Thisis a word that Carroll deferred from defining until a few years later, in thepreface to his lengthy stand-alone nonsense poem The Hunting of the Snark, published in 1876, and in which both thejubjub bird and the bandersnatch reappear. Two of this latter poem's maincharacters hear the jubjub bird's very scary cry (described as a shrill andhigh scream), whereas a third main character is attacked by the bandersnatchand is driven insane after trying to bribe it. In this composition's preface,Carroll states that 'frumious' is a composite of 'fuming' and 'furious', soclearly the bandersnatch is a beast best avoided!

Meanwhile, here is a very charming butsomewhat idiosyncratic illustration from 1902 depicting the jubjub bird and thebandersnatch, prepared by Peter Newell (1862-1924), an American artist andwriter of children's books, in which neither of these creatures seems even remotelybelligerent, let alone frumious:

Illustration of the jubjub bird and the bandersnatch by PeterNewell in a 1902 edition of Through theLooking-Glass (public domain)

Illustration of the jubjub bird and the bandersnatch by PeterNewell in a 1902 edition of Through theLooking-Glass (public domain)

No further creatures appear in'Jabberwocky', but those that are present there have frustrated and fascinatedgenerations of readers eager to learn more about them, and no doubt willcontinue to so for the foreseeable future.

Except for this ShukerNature blogarticle's opening photograph of a mome rath, which I created by digitallymanipulating a public-domain stock photo of a typical shorter-snouted pink porker, all mome rath illustrations included here (as well as the firstjabberwock illustration) were created by MagicStudio.

Ina mome rath galaxy far, far away, Throughthe Looking-Glass meets The Lord ofthe Rings, or could it be Planet ofthe Pigs?

Ina mome rath galaxy far, far away, Throughthe Looking-Glass meets The Lord ofthe Rings, or could it be Planet ofthe Pigs?

Karl Shuker's Blog

- Karl Shuker's profile

- 45 followers