The Tortoise and the Hare in Alloy

If you’ve done your share of leetcode-style interviewing, and you’re above a certain age, you may have been asked during a technical screen to write a program that determines if a linked list contains a cycle. If the interviewer was really tough on you, they might have asked how to implement this in O(1) space.

There’s a well-known O(1) algorithm for finding cycles in linked lists, attributed to Robert Floyd, called the tortoise and the hare. I’ve previously written about modeling this algorithm in TLA+. In this post, I’m going to do it in Alloy. Version 6 of Alloy added support for temporal operators, which makes it easier to write TLA+ style models, with the added benefit of Alloy’s visualizer. This was really just an excuse for me to play with these operators.

You can find my model at https://github.com/lorin/tortoise-hare-alloy/

Brief overview of the algorithmBasic strategy: define two pointers that both start at the head of the list. At each iteration, you advance one of the pointers (the tortoise) by one step, and the other (the hare) by two steps. If the hare reaches the tail of the list, there are no cycles. If the tortoise and the hare ever point to the same node, there’s a cycle.

With that out of the way, let’s model this algorithm in Alloy!

Linked listsLet’s start off by modeling linked lists. Here’s the basic signature.

sig Node { next : lone Node}Every linked list has a head. Depending on whether there’s a cycle, it may or may not have a tail. But we do know that it has at most one tail.

one sig Head in Node {}lone sig Tail in Node {}Let’s add a fact about the head, using Alloy reflexive transitive closure operator (*).

fact "all nodes are reachable from the head" { Node in Head.*next}You can think of Head.*next as meaning “every node that is reachable from Head, including Head itself”.

Finally, we’ll add a fact about the tail:

fact "the tail is the only node without a successor" { all n : Node | no n.next <=> n = Tail}We can now use Alloy to generate some instances for us to look at. Here’s how to tell Alloy to generate an instance of the model that contains 5 nodes and has a tail:

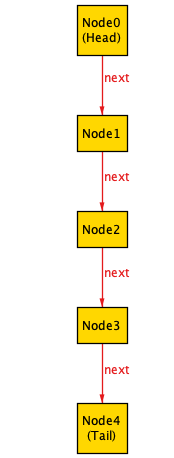

acyclic: run { some Tail } for exactly 5 NodeThis is what we see in the visualizer:

We can also tell Alloy to generate an instance without a tail:

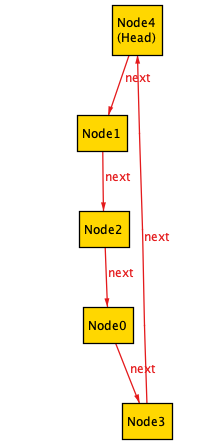

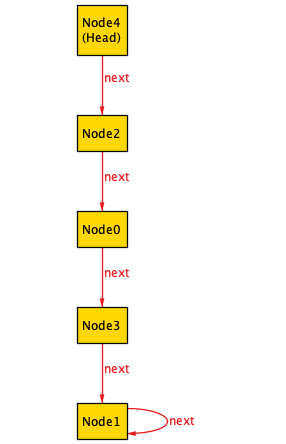

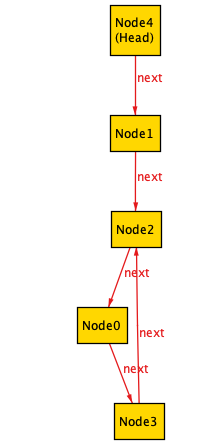

cycle: run { no Tail } for exactly 5 NodeHere are three different instances without tails:

Tortoise and hare tokens

Tortoise and hare tokensThe tortoise and the hare are pointers to the nodes. However, I like to think of them like tokens moving along a game board, so I called them tokens. Here’s how I modeled them:

abstract sig Token { var at : Node}one sig Tortoise, Hare extends Token {}Note that the Token.at field has a var prefix. That’s new in Alloy 6, and it means that the field can change over time.

As in TLA+, we need to specify the initial state for variables that change over time. Both tokens start at the head, which we can express as a fact.

fact init { Token.at in Head}Next, as in TLA+, we need to model how variables change over time.

Here’s the predicate that’s true whenever the tortoise and hare take a step. Alloy uses the same primed variable notation as TLA+ to refer to “the value of the variable in the next state”. In TLA+, we’d call this kind of predicate an action, because it contains primed variables:

pred move { Tortoise.at' = advance[Tortoise.at] Hare.at' = advance[advance[Hare.at]]}This predicate uses a helper function I wrote called advance which takes a pointer to a node and advances to the next node, unless it’s at the tail, in which case it stays where it is:

fun advance[n : Node] : Node { (n = Tail) implies n else n.next}We can run our model like this, using the always temporal operator to indicate that the move predicate is true at every step.

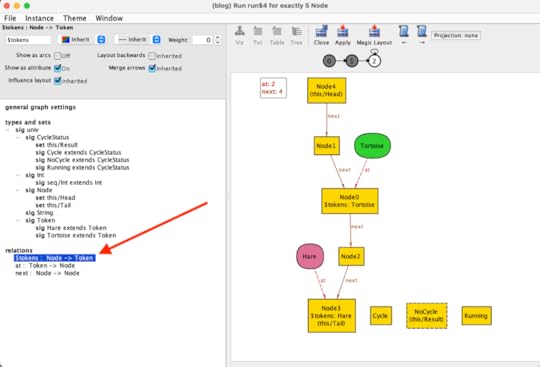

run {always move} for exactly 5 NodeHere’s a screenshot of Alloy’s visualizer UI for one of the traces. You can see that there are 5 states in the trace, and it’s currently displaying state 2.

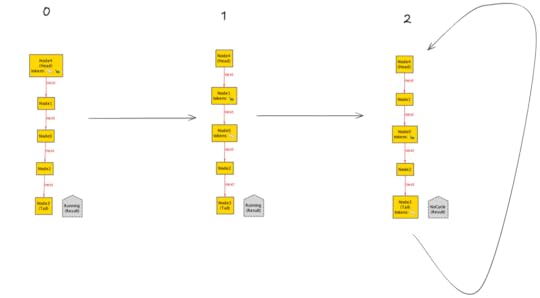

Here are all of the states in the trace:

It’s confusing to follow what’s happening over time because Alloy re-arranges the layout of the nodes at the different steps. We’ll see later on this post how we can configure the visualizer so to make it easier to follow.

Output of the algorithmSo far we’ve modeled the movement of the tortoise and hare tokens, but we haven’t fully modeled the algorithm, because we haven’t modeled the return value, which is supposed to indicate whether there’s a cycle or not.

I modeled the return value as a Result signature, like this:

abstract sig CycleStatus {}one sig Cycle, NoCycle, Running extends CycleStatus {}var one sig Result in CycleStatus {}You can think of Result as being like an enum, which can take on values of either Cycle, NoCycle, or Running.

Note that Result has a var in front, meaning it’s a variable that can change over time. It starts off in the Running state, so let’s augment our init fact:

fact init { Token.at in Head Result = Running}Let’s also define termination for this algorithm. Our algorithm is done when Result is either Cycle or NoCycle. Once it’s done, we no longer need to advance the tortoise and hare pointers. We also don’t change the result once the program has terminated.

pred done { Result in Cycle + NoCycle Tortoise.at' = Tortoise.at Hare.at' = Hare.at Result' = Result}We need to update the move action so that it updates our Result variable. We also don’t want the move action to be enabled when the algorithm is done (no need to keep advancing the pointers), so we’ll add an enabling condition. As a result, move now looks like this:

pred move { // enabling condition Result = Running // advance the pointers Tortoise.at' = advance[Tortoise.at] Hare.at' = advance[advance[Hare.at]] // update Result if the hare has reached the tail // or tortoise and hare are at the same node Hare.at' = Tail implies Result' = NoCycle else Hare.at' = Tortoise.at' implies Result' = Cycle else Result' = Result}The syntax for updating the Result isn’t as nice as in TLA+: Alloy doesn’t have a case statement. It doesn’t even have an if statement: instead we use implies/else to achieve if/else behavior.

We can now define the full spec like this:

pred spec { always ( move or done )}And then we can ask the analyzer to generate traces when spec is true, like this:

example: run { spec } for exactly 5 NodeImproving the visualizationFinally, let’s make the visualization nicer to look at. I didn’t want the tortoise and hare to be rendered by the visualizer as objects separate from the nodes. Instead I wanted them to be annotations on the node.

The analyzer will let you represent fields as attributes, so I could modify the Node signature to add a new field that contains which tokens are currently occupying the node:

sig Node { next : lone Node, var tokens : set Token //But I didn’t want to add a field to my model.

However, Alloy lets you define a function that returns a Node -> Token relation, and then the visualizer will let you treat this function like it’s a field. This relation is just the inverse of the at relationship that we defined on the Token signature:

// This is so the visualizer can show the tokens as attributes // on the nodesfun tokens[] : Node -> Token { ~at}Now, in the theme panel of the visualizer, there’s a relation named $tokens.

You can also rename things. In particular, I renamed Tortoise to  and Hare to

and Hare to  as well as making them attributes. Here’s a screenshot after the changes:

as well as making them attributes. Here’s a screenshot after the changes:

Here’s an example trace when there’s no cycle. Note how the (Result) changes from Running to NoCycle

Much nicer!

Checking a propertyDoes our program always terminate? We can check like this:

assert terminates { spec => eventually done}check terminates for exactly 5 NodeThe analyzer output looks like this:

Solving...No counterexample found. Assertion may be valid. 9ms.In general, this sort of check doesn’t guarantee that our program terminates, because our model might be too small.

We can also check for correctness. Here’s how we can ask Alloy to check that there is a cycle in the list if and only if the program eventually terminates with Result=Cycle.

pred has_cycle { some n : Node | n in n.^next}assert correctness { spec => (has_cycle <=> eventually Result=Cycle)}check correctness for exactly 5 NodeNote that we’re using the transitive closure (^) in the has_cycle predicate to check if there’s a cycle. That predicate says: “there is some node in that is reachable from itself”.

Further readingFor more on Alloy 6, check out the following:

Alloy 6 official release announcementThe online book Formal Software Design with Alloy 6 by Julien Brunel, David Chemouil, Alcino Cunha and Nuno MacedoHillel Wayne’s post: Alloy 6: It’s About TimeThe Time section in Hillel’s Alloy docsAlloy’s very easy to get started with: I recommend you give it a go!