TTR: the out-of-control metric

I’m currently reading The Machine That Changed The World. This is a book written back in 1990 comparing Toyota’s approach to automobile manufacturing to the approach used by American car manufacturers. It’s one of the earlier books that popularized the concept of lean manufacturing in the United States.

The software world has drawn a lot of inspiration from lean manufacturing over the past two decades, as is clear from the titles of influential software books such as Implementing Lean Software Development by Tom Poppendieck and Mary Poppendieck (2006), The Principles of Product Development Flow: Second Generation Lean Product Development by Don Reinersten (2009), The Lean Startup by Eric Ries (2011), Lean UX by Jeff Gothelf and Josh Sieden (first published in 2013), and Accelerate: The Science of Lean Software by Nicole Forsgren PhD, Jez Humble, and Gene Kim (2018). Another signal is the proliferation of Kanban boards, which are a concept taken from Toyota. I’ve also seen continuous delivery compared to single-piece flow from lean manufacturing, although I suspect that’s more a case of convergent evolution than borrowing.

In The Machine That Changed The World, the authors mention in passing how Toyota uses the five-whys problem identification technique. I had forgotten that five whys has its origins in manufacturing. This post isn’t about five whys, but it is about how applying concepts from manufacturing to incidents can lead us astray, because of assumptions that turn out to be invalid. For that, I’m going to turn to W. Edwards Deming and the idea of statistical control.

Deming & Statistical controlDeming is the famous American statistician who had enormous influence on the Japanese manufacturing industry in the second half of the twentieth century. My favorite book of his is Out of the Crisis, originally published in 1982, which I highly recommend.

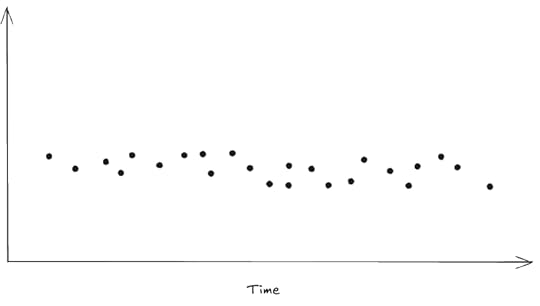

One of the topics Deming wrote on was about a process being under statistical control, with the focus of his book being on manufacturing processes in particular. For example, imagine you’re tracking some metric of interest (e.g., defect rate) for a manufacturing process.

(Note: I have no experience in the manufacturing domain, so you should treat this is as a stylized, cartoon-ish view of things).

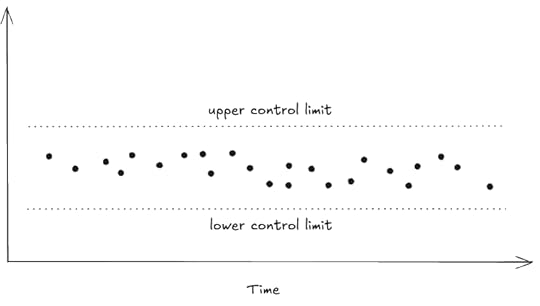

Deming argued that when a process is under statistical control, focusing on individual defects, or even days, where the defects are higher than average, is a mistake. To make this more concrete, you can compute an upper control limit and lower control limit based on the statistics of the observed data. There is variation inherent in the process, and focusing on the individual data points that happen to be higher than the average won’t lead to actual improvements.

The process with computed upper and lower control limits. This graph is sometimes called as a control chart.

The process with computed upper and lower control limits. This graph is sometimes called as a control chart.Instead, in order to make an improvement, you need to make a change to the overall system. This is where Toyota’s five-whys would come in, where you’d identify a root cause, a systemic issue behind why the average rate is as high at is. Once you identified a root cause, you’d apply what Deming called the Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle, where you’d come up with an intervention, apply it, observe whether the intervention has actually achieved the desired improvement, and then react accordingly.

I think people have attempted to apply these concepts to improving availability, where time-to-resolve (TTR) is the control metric. But it doesn’t work the way it does in manufacturing. And the reason it doesn’t has everything to do with the idea of statistical control.

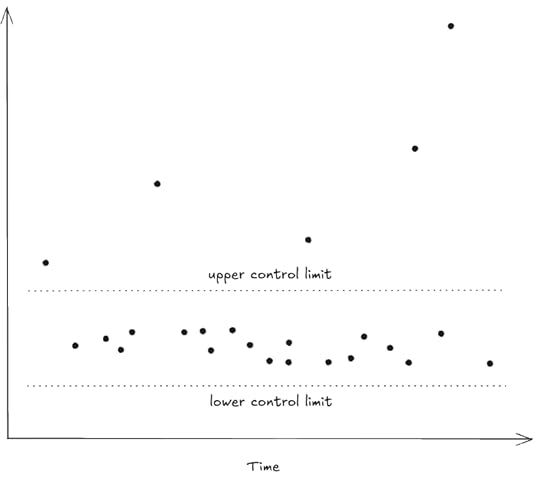

Out of controlNow, let’s imagine a control chart that looks a little different.

In the chart above, there are multiple points that are well outside the control limits. This is a process that is not under statistical control.

Deming notes that, when a process is not under statistical control, statistics associated with the process are meaningless:

Students are not warned in classes nor in the books that for analytic purposes (such as to improve a process), distributions and calculations of mean, mode, standard deviation, chi-square, t-test, etc. serve no useful purpose for improvement of a process unless the data were produced in a state of statistical control. – W. Edwards Deming, Out of the Crisis

Now, I’m willing to bet that if you were to draw a control chart for the time-to-resolve (TTR) metric for your incidents, it would look a lot more like the second control chart than the first one, that you’d have a number of incidents whose TTRs are well outside of the upper control limit.

The reason I feel confident saying this is because when an incident is happening, your system is out of control. This actually is a decent rough-and-ready definition of an incident: an event when your system goes out of control.

Time-to-resolve is a measure of how long your system was out of control. But because your system was out of control, then it isn’t a meaningful metric to perform statistical analysis on. As per the Deming quote above, mean-time-to-resolve (MTTR) serves no useful purpose for improvement.

Anyone who does operations work will surely sympathize with the concept that “a system during an incident is not under statistical control”. Incidents are often chaotic affairs, and individual events (a chance ordering by the thread scheduler, a responder who happens to remember a recent Slack message, someone with important knowledge happens to be on PTO) can mean the difference between a diagnosis that takes minutes versus one that takes hours.

As John Allspaw likes to say, a large TTR cannot distinguish between a complex incident handled well and a simple incident handled poorly. There are too many factors that can influence TTR to conclude anything useful from the metric alone.

ConclusionTo recap:

When a system is out of control, statistical analysis on system metrics are useless as a signal for improving the system.Incidents are, by definition, events when the system is out control.TTR, in particular, is a metric that only applies when the system is out of control. It’s really just a measure of how long the system was out of control.

Now, this doesn’t mean that we should throw up our hands and say “we can’t do anything to improve our ability to resolve incidents.” It just means that we need to let go of a metrics-based approach.

Think back to Allspaw’s observation: was your recent long incident a complex one handled well or a simple one handled poorly? How would you determine that? What questions would you ask?