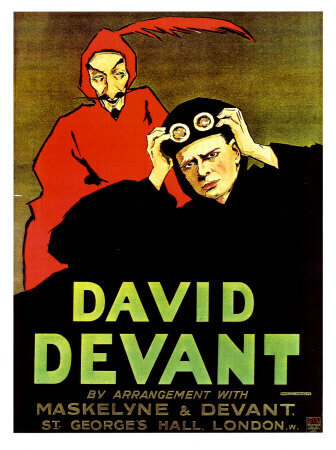

David Devant

David Devant, the stage name of David Wighton taken from the title of a painting David devant Goliath, was a successful magician, hugely popular with the British public. “The Mascot Moth” is considered to have been his masterpiece, created in 1905. In full view of the audience and in the centre of a fully lit stage, a woman, dressed in a moth-like costume, vanishes out of sight as she folds her wings in and the conjurer tries to grasp her, even though the figure is not concealed in any way during the illusion.

Part of Devant’s appeal was his desire to incorporate his illusions into short magical plays, based upon a deeply held conviction that the magician was “a story teller and should hold the attention of the audience by telling them the most impossible fairy tales, and by persuading them to believe that these stories are true”. By the standards of the day when magicians were often lofty and pretentious, his style was informal, witty and charming.

Devant became the first president of the Magic Circle in 1905 and appeared in the first royal command variety show in 1912. However, he was also no stranger to controversy. One of the golden rules amongst magicians is that the secrets of their trade, the precise mechanics of each trick or illusion, should be a closely guarded secret. Indeed, the Magic Circle had a rule prohibiting its members from “exposing to the public, in any manner whatsoever, any secret of the Art of Magic”.

However, between 1908 and 1909 Devant wrote a series of articles entitled “Tricks for Everyone” which were published in the Royal Magazine. His audacity earned him the disfavour of some of his colleagues and he was forced to resign, but such was his status as a magician that his departure cause a deep division in the ranks which was only healed when he was reinstated as an ordinary member in 1912.

Forced to retire from performing in public in 1919 because of a debilitating progressive palsy, by 1936 Devant was almost totally paralysed and confined to a wheelchair. He courted controversy once more that year by publishing Secrets of My Magic in which he disclosed the secrets of the magic tricks he had invented. The Magic Circle once more demanded his resignation.

In his defence Devant argued in the Sunday Express that “the tricks I had exposed were my own, so I did not think I had broken any rule. I owe it to posterity to give to the world my secrets before I die. I don’t think I shall live much longer. Exposing tricks or illusions—providing they are not someone else’s new invention—is good for the profession. It stimulates public interest in magic and forces magicians to seek new tricks rather than to stagnate with some that are centuries old. The Magic Circle seems to think that it is the mechanics of a trick that are the secrets of its success. In my view, it is only the artistry of the performer that can make it magic.”

The Magic Circle felt that it had no option but to uphold its rule “with the greatest regret” and expel Devant from membership, although in 1937, by which time he had been admitted to the Royal Home for Incurables at Putney, he was offered an Honorary Life Membership, which he graciously accepted.

A statue in his honour was unveiled at the Centre for Magic Arts in Euston in 1998 and his name lives on with the David Devant Award, which, since 1999, has recognised those who have made a significant contribution to the world of magic. The winner this year (2024) was Gay Blackstone.