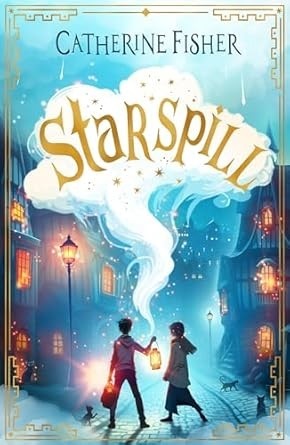

Review of Starspill by Catherine Fisher, pub. Firefly Press 2024

“Zac buried his head under the pillow. ‘Go away. I’m asleep.’

“It’s freezing out here. Hurry up!’

He knew it was the kitten. The cats of Starspill were cool and haughty and rarely spoke to humans if they could help it…”

At this point a lesser writer would waste time inventing an explanation for how it comes about that the cats of Starspill can speak to humans at all. Fisher simply gives it for a fact: this is how things are in the world I have made, where fog permanently smothers the town so that artificial light is always needed; where a wolf has swallowed the sun and where stars, or pieces of stars, hot enough to burn the hand but small enough to fit in a pocket, periodically fall and are made into lamps. Says the Storyteller; ‘And thus is my tale told. Yet there is no end, for the tale goes on and we are inside it.’

When one has created a story-world, the next necessary thing is to imagine convincingly how things work inside it. The lack of natural light, and the inadequacy and price of the substitutes (candles and the star-lamps, which mostly don’t function much better than oil-lamps, or are beyond people’s means), have had a predictable effect; “hardly anyone read much now, as light was so expensive”. In consequence school ends at an early age for most, and though his friend Alys is still there, our protagonist Zac, who must be somewhere in his early teens, has left to work for his brother Gryff, star-collector and lamp-maker.

It is a novel of several linked quests, and in that way reminiscent of the old Welsh legend of Culhwch and Olwen, of which Fisher published a retelling for children earlier this year. The plot concerns how Zac and Alys (the A-Z as one might say), helped by a mysterious bookseller and under orders from the town’s imperious cats, try to find and win three embers of the lost sun, which if combined will defeat the fog – an end unpopular with some, who have come to worship darkness and a wolf-cult, while others have ceased to believe that things were, or ever could be different:

“’Would you like it if the Sun came back?’ Zac said suddenly.

She stared at him. ‘Not much chance of that.’

‘But if?

‘Blue sky, heat, green things growing, birds singing? It’s a myth, Zac, just a story. It could never happen. Things were never that good.’”

If you wanted, you could easily enough see allegory in this novel. The map which illuminates the labyrinth through which the questers must travel is in a bookshop. Aurelian the bookseller explains:

“It was a secret way of travelling, a system of hidden ways through the world. […] They say there is no time there, that you can enter and be a hundred miles away in a moment. There are certain secret entrances – they are called Thresholds and the Map shows where they are”.

But it isn’t as simple as “books = doors into new worlds” or “fog = ignorance” (or perhaps, given Zac’s divided feelings about it, “familiarity”). It makes more sense to see fog, wolf etc as folk-tale archetypes that can have many different incarnations in the real world. In this particular real world, there is a basic conflict between those who fear the light because it “will show you all the foolish and dangerous things that should not be seen” and those who believe that “we need to see and understand our world”. This conflict has been going on throughout history and it is not hard to think of other examples of it. I should imagine the Taliban dislike most books, but if they were capable of understanding this one, they would be especially averse to it.

Zac is a likeable protagonist, but for most readers the star will be the self-possessed kitten who shares his adventures. It is also oddly pleasing that while the humans in the story have various more or less complex motives for wanting or not wanting the sun back, the motivation of the town’s cats is simple: they just want to be able to bask in sunlight. Fittingly, the book is dedicated to the author’s own two cats.