From a Gilded Age senator’s home to a 1920s speakeasy, the unusual life of a faded Midtown brownstone

Over the years I’ve often wondered about the brownstone at 14 East 44th Street, a faded dowager hidden in the shadow of the office towers around Grand Central Terminal.

Snug between its glass and limestone neighbors, it likely started out as part of a posh row of upper middle class dwellings in the 1860s or 1870s. In those decades, blocks of uniform brownstones rose all over Manhattan, especially in the upper reaches of Murray Hill and today’s Midtown.

And what’s with the three-story facade covering the original stoop and parlor windows, slapped on to give the brownstone a more stylish appearance, I gather? It’s as if a new owner began redoing the brownstone with Romanesque touches and then gave up.

The research didn’t lead me to the brownstone’s origin story or an explanation of its strange facade alteration.

But it did reveal stories about the prominent New Yorker who occupied the house in the Gilded Age, and then the bizarre turn the brownstone took in the 1920s as a speakeasy set up by the federal government to trap bootleggers bringing liquor to Gotham.

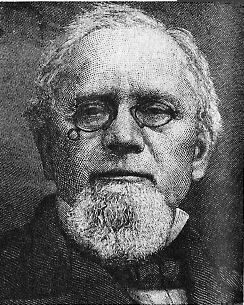

First, the late 19th century owner who lived here with his family. Webster Wagner (at left) was a state senator who made his fortune in the railroad business—not by buying rail lines (like his close friends, the Vanderbilts) but as the inventor of the sleeping car.

A native of upstate New York, Wagner had a spectacular mansion in Palatine, near Albany, and a “very nice house in New York City, in which his family spent winters,” notes this biography.

When Wagner and his family—his wife, son, and four daughters—took up residence in this uptown brownstone isn’t clear. But they held a splendid wedding reception for his youngest daughter, Annette, here on December 2, 1880 after a ceremony at Holy Trinity Church on Madison Avenue and 42nd Street.

With 1,500 invitations sent out, it was deemed by the New York Times as one of winter’s foremost society nuptials.

“The reception from 8:30 until 11 o’clock was almost a crush,” the Times reported, after chronicling the stunning floral decorations in the house’s two parlors. “One could scarcely move without running against a senator, elbowing a railway president, or nudging a millionaire.”

As he did with his other married offspring, Wagner gifted the newlyweds with a house of their own, “a magnificent up-town residence in the immediate neighborhood of his own,” wrote the Times.

Wagner lived in the brownstone until his death in 1882, ironically in a terrible train collision at Spuyten Duyvil as he was returning home from Albany. His grief-stricken family received throngs of guests in the same parlors where Annette’s wedding was joyously celebrated two years earlier, reported the New York Times.

Through the end of the Gilded Age and the early decades of the 20th century, the brownstone changed hands. by 1920, Prohibition arrived. Taverns and bars were forced out of business—and hundreds of speakeasies appeared in the city with no shortage of thirsty customers eager to enjoy New York nightlife with alcohol.

That began the former residence’s second life as a secret bar (above, in 1927). When it opened in 1925 as “The Bridge Whist Club,” it seemed like a regular Midtown speakeasy—even somewhat chic, as this newspaper illustration above shows. The place was close to the action on Broadway, and the “club rooms” operated on the second floor.

“The saloon was filled with smoke and the jabbering of customers lining the mahogany bar,” wrote a reporter for a wire story. “Bartenders buzzed about filling schooners with real beer, chipping ice for martinis and Manhattans. In the curtained back room, men with girls whose cheeks were coated with rouge yelled drunkenly for more champagne.”

But apparently, bootleggers began to catch on that something wasn’t right with the place. Every time they came to deliver alcohol, it was “mysteriously seized,” as one 1926 news story put it.

Soon a story emerged. After the owner sublet the profitable speakeasy, it fell into the hands of A. Bruce Bielaski, part of a Treasury department prohibition enforcement unit that used wiretaps and eavesdropping devices stashed in lamps to snare “Prohibition violators,” according to Burton W. Peretti in his book, Nightlife City: Politics and Amusement in Manhattan.

The Bridge Whist Club “violated the Volstead Act in the name of its enforcement of too many pathbreaking ways for Washington or the public to accept,” wrote Peretti. “Those arrested at the club were ultimately set free.”

By the 1940s, 14 East 44th Street went in another direction: it became the site of a restaurant and club called Gamecock. Through the 20th century, the upper floors seem to have transformed into office space, and in recent years the ground floor served as a deli-restaurant, now closed.

These days, the brownstone has its cornice and window lintels intact, though the glamour that attracted Webster Wagner and the speakeasy crowd has faded away. It’s the lone surviving brownstone on the block and witness to more than 150 years of city life, and the house has more stories to tell.

[Third image: The Silent Forgotten via Findagrave.com; fifth and sixth images: Elmira Star Gazette; seventh image: The Brooklyn Citizen]