Weird Fiction Old, New, and In-Between II: Weirding the World We Know – Rafe McGregor

The second of six blog posts exploring the literary andphilosophical significance of the weird tale, the occult detective story, and theecological weird. The series suggests that the three genres of weird fiction dramatizehumanity’s cognitive and evolutionary insignificance by first exploring thelimitations of language, then the inaccessibility of the world, and finally thealienation within ourselves. This post introduces the mismatch betweenconception and reality.

Weird Tales

I concluded part I by endorsing literary critic S.T. Joshi’s definitionof the weird tale as essentially rather than superficially philosophical invirtue of presenting or representing a fully-fledged and fleshed-out worldviewand identifying the canon of weird fiction as the work of: Arthur Machen(1863-1947), Algernon Blackwood (1869-1951), William Hope Hodgson (1877-1918), EdwardPlunkett (1878-1957, writing under his aristocratic title Lord Dunsany), and H.P.Lovecraft (1890-1937). Joshi’s definition also restricts the weird tale tofiction published within a sixty-year period that begins in 1880 and ends in1940 and he deals with subsequent publications in The Modern Weird Tale: ACritique of Horror Fiction. The ‘modern’ or ‘new’ weird and its relation to the‘ecological’ weird will be discussed in part V. Benjamin Noys and TimothyMurphy concurwith Joshi’s dating and identify the source of the name of the genre as thepulp magazine Weird Tales. Before introducing this magazine, I want tomention three of Lovecraft’s less-talented contemporaries. Edgar Rice Burroughs(1875-1950, writing under the penname Norman Bean) is best known for Tarzanof the Apes (serialised in The All-Story in 1912), but also authoredthe John Carter series, which began with Under the Moons of Mars (serialisedin The All-Story in 1911). Similarly, Robert E. Howard (1906-1936) is bestknown for Conan the Barbarian (short stories published in Weird Talesfrom 1932), but is also the creator of Solomon Kane (short stories published inWeird Tales from 1928). Finally, Fritz Leiber (1910-1992), is best knownfor Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser (short stories published in Unknown from 1939),but published some outstanding weird fiction, beginning with the collection Night’sBlack Agents (1947).

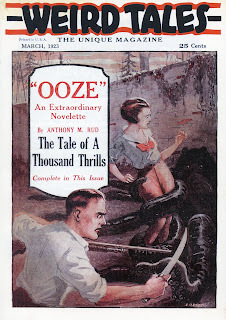

Weird Tales was founded in 1922, during the peak of the pulp era and twoyears after its famous crime fiction counterpart, Black Mask (whichlaunched the career of Raymond Chandler). Its first issue (pictured) waspublished in March 1923 and within a decade the magazine was publishing theLovecraft Mythos, Solomon Kane, Conan, and Seabury Quinn’s Jules de Grandin, anoccult detective series that would run to nearly one hundred instalments. Thefirst Lovecraft Mythos story published was ‘The Hound’, in February 1924. Asidefrom the significance of the magazine in naming and consolidating the type ofnarrative we now refer to as the weird tale, it is also significant inindicating the need for a supplement to Joshi’s definition. Weird fiction notonly explores, expresses, and experiments with the worldviews of its authors,but is also essentially rather than superficially hybrid in character,crossing, slipping, and bending between and among genres. The Carter, Kane, andFafhrd and Mouser series are all weird fiction, but Fredric Jameson regards Carter as theorigin of American science fiction, Fafhrd and the Mouser are (along withConan) acknowledged as inaugurating fantasy fiction, and Kane is as much historyas fantasy. The pulp era died a slow death after the Second World War,initiated by first a wartime paper shortage and then the rise of television asthe dominant medium of light entertainment in the nineteen fifties. WeirdTales published its final issue in September 1954.

In-Between Old and New

The five decades between the folding of Weird Tales and thecoining of the label ‘New Weird’ (by John M. Harrison in 2002 or 2003) are complex whenit comes to the development of weird fiction and I make no pretence to insiderknowledge or even of being able to produce convincing evidence of my take onthis period. That take has two key features: the influence of August Derlethand a second division of the genre into US and UK traditions. Derleth was apulp fiction author and correspondent of Lovecraft who, along with DonaldWandrei (another pulp fiction author and Lovecraft correspondent), founded Arkham House in 1939 in order to publish Lovecraft’s workposthumously and self-publish their own work. Joshi is particularly critical ofDerleth, who invented the ‘Cthulhu Mythos’, and his misrepresentation ofLovecraft’s work and worldview. I am once again largely in agreement, but wemust also accept that if Derleth had not appropriated Lovecraft’s legacy hewould be as unknown now as, for example, Quinn is. While Lovecraft imitatorsthrived on both sides of the Atlantic following the Weird Tales era, Ithink it helpful to identify two traditions of canonical weird fiction,understood as having unquestionable literary merit (however one chooses todefine that quality).

In the UK, a tradition influenced less by Lovecraft and more by Machenand Blackwood – as well as Walter de la Mare – emerged in the work of JohnWilliam Wall (1910-1989, writing under the penname Sarban) and Robert Aickman(1914-1981). Wall published very little and is best known for his novella, TheSound of His Horn (1952). Aickman is best known for the forty-eight storieshe referred to as ‘strange’ tales, the first three of which were published in WeAre for the Dark: Six Ghost Stories (1951, the other three in thecollection were by the novelist Elizabeth Jane Howard). To these two, I shalladd J.G. Ballard (1930-2009). Although Ballard, to whom I shall return in partV, is usually considered to be a literary rather than popular fiction author (adichotomy I regard as not only erroneous, but malicious), he began his careeras a science fiction writer, part of the ‘New Wave’ of experimental and politicalscience fiction in the nineteen sixties and seventies. The novella The Windfrom Nowhere (1961) and the collection The Terminal Beach (1964) areexemplary weird fiction.

In the US, a tradition more obviously influenced by Lovecraft and eitherexplicitly part of his mythos or self-consciously an extension or revisionthereof emerged in the work of Thomas Ligotti (b.1953), Caitlín R. Kiernan(b.1964, pictured), and Victor LaValle (b.1972). Ligotti has publishedrelatively little and I return to his work in the next section. In contrast,Kiernan has published a vast oeuvre since 1995, including more than ten novelsand over two hundred and fifty works of shorter fiction. Their TinfoilDossier (2017-2020) trilogy of novellas is my favourite at the time ofwriting, but The Drowning Girl: A Memoir (2012) demonstrates anall-too-rare ability to extend the weird tale to novel length withoutstretching either quality or credibility. LaValle has published a dozen or sonovels, novellas, graphic novels, and short story collections since 1999. Hisnovella, The Ballad of Black Tom (2016), is a magnificent reimaginingof Lovecraft’s ‘The Horror at Red Hook’ (first published in Weird Talesin January 1927) and, in my opinion, far superior to Matt Ruff’ssimilarly-themed Lovecraft Country, published in the same year.

Conception and Reality

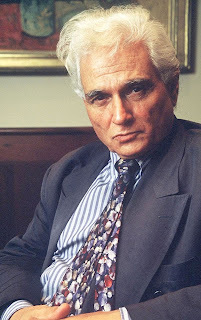

In my review of Songs of a Dead Dreamer andGrimscribe(2016), I described Ligotti as exploring, expressing, and experimenting with aworldview that could be called deconstructive, after the French philosopherJacques Derrida (1930-2004, pictured). There has been a great deal of nonsensewritten about (and some would say by) Derrida, who developed theapproach in the nineteen sixties and was a global public intellectual by thetime of his death, but the basic idea behind deconstruction is simple: humanbeings (subjective experience) can only gain access to the real world (objectivereality) through concepts, which are articulated through language. The worry,which stems from curiosities such as the fact that languages not only usedifferent words for the same concept, but have different concepts that cannotbe translated in their entirety, is that no human language and therefore nohuman conception maps perfectly onto reality. There is obviously plenty ofoverlap – otherwise we would not be able to build bridges, cure diseases,invent the internet, and fly to the moon – but there is no identity relationbetween concept and reality. This insight about the limitations of language,the way in which words fail to make the concrete and abstract objects they identifypresent, originated with the Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure (1857-1913).Derrida’s innovation was to demonstrate that the system of signs constituting aparticular language (such as Modern English) is unstable because that system isinconsistent over both space (such as the differences between contemporary UKand US English) and time (such as the difference between Shakespeare’s earlyModern English and contemporary Modern English in the UK).

The upshot of this is that there is a difference between the world as wethink it is and the world as it really is, where aspects of the latter remainpermanently inaccessible to us. I shall have more to say about thisinaccessibility in part IV. In consequence of language failing to providedirect access to reality, the world in which we live is co-constructed by humanintelligibility and inaccessible reality, a dichotomy very roughly equivalentto the distinction between culture and nature. This space between the world wecreate for ourselves and the real world is both frightening and liberating. Ifmuch more of our reality than commonsense suggests is a question of culturerather than nature, then much more of our reality can be changed for thebetter. I emphasised this emancipatory potential in my own introduction to literarytheory, butLigotti focuses on the fear and disgust the mismatch between conception andreality evokes. He scrapes away at the difference between subjective perceptionand objective reality to make it larger and more frightening and this is theworldview that emerges in Songs of a Dead Dreamer and Grimscribe, MyWork Is Not Yet Done: Three Tales of Corporate Horror (2002), TeatroGrottesco (2006), The Spectral Link (2014), and his other work.Ligotti’s short stories are not only the most disturbing I have ever read, but distiland hone something was present to a lesser extent in Machen, Blackwood,Hodgson, Plunkett, and Lovecraft. With Ligotti in mind, I propose a furtheramendment to define weird fiction as: philosophical in virtue of presenting orrepresenting a fully-fledged and fleshed-out worldview, generically hybrid incharacter, and foregrounding the difference between the world as we think it isand the world as it actually is. This latter quality is precisely what thereferences to the uncanny or unhomely mentioned in part I are trying to convey,but ‘weird’ seems a much more accurate description to me.

Recommended Reading

Fiction

Thomas Ligotti, Teatro Grottesco, Durtro Press (2006).

Caitlín R. Kiernan, The Drowning Girl: A Memoir, Roc Books (2012).

J.G. Ballard, The Crystal World, Jonathan Cape (1966).

Nonfiction

H.P. Lovecraft, Notes on Writing WeirdFiction, AmateurCorrespondent (1937).

Alan Moore, Preface, The Call of Cthulhu and Other Weird Stories, TheFolio Society (2017).

Mark Bould & Steven Shaviro (eds.), This is Not a Science FictionTextbook, Goldsmiths Press (2024).