The power of enemies and the dangers of “friends”

James G. Blaine and Roscoe Conkling benefited from the enemies they made. Their allies? Not so much.

Enemies were often more useful for James G. Blaine and Roscoe Conkling than friends.

The rivalry between Blaine and Conkling helped define the 1870s and early 1880s, but their 18-year battle for supremacy in the Republican Party is replete with examples of how they took aim at other opponents to define and position themselves on the great issues of the day.

These spats often proved more useful than allies who were foisted on them by circumstance. Attack, whether the target was Andrew Johnson or Ben Butler, strengthened their standing with Republicans. At the same time, friends of Blaine and Conkling proved to be serious liabilities at key moments in their careers.

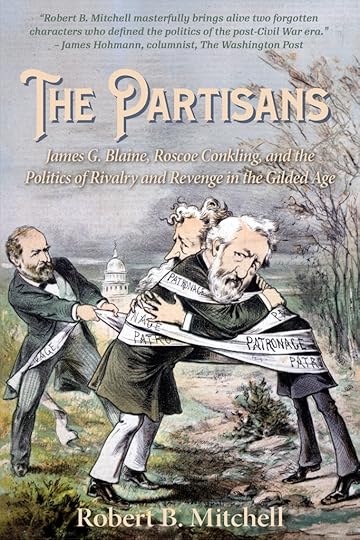

The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age is coming out Oct. 15 from Edinborough Press.

The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age is coming out Oct. 15 from Edinborough Press.Andrew Johnson: In the aftermath of the Civil War, no figure in American politics infuriated Republicans quite like the Tennessee Democrat chosen by Abraham Lincoln as his vice-presidential running mate in 1864.

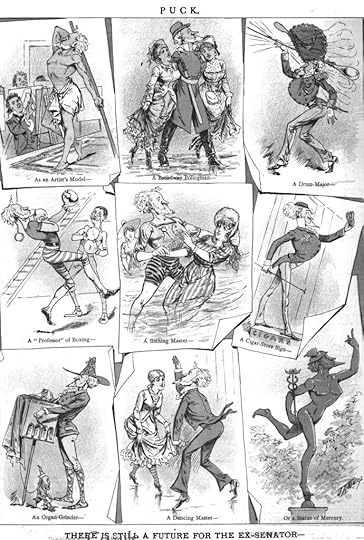

Roscoe Conkling as rendered in Puck

Roscoe Conkling as rendered in PuckAlthough he signaled in the days after Lincoln’s assassination that he would be tough on defeated rebels, Johnson pursued a conciliatory policy toward the former Confederacy. He pardoned thousands of former Confederates and rushed to readmit rebellious Southern states to full participation in national affairs. He fought bitterly against congressional Republicans, who were infuriated with his lenient approach.

Johnson took his case to the people in the infamous “Swing Around the Circle” speaking tour of 1866. It didn’t go well, as Blaine observed in the second volume of his Twenty Years of Congress. “Wit and sarcasm were lavished at the expense of the president, gibes and jeers and taunts marked the journey from its beginning to its end.”

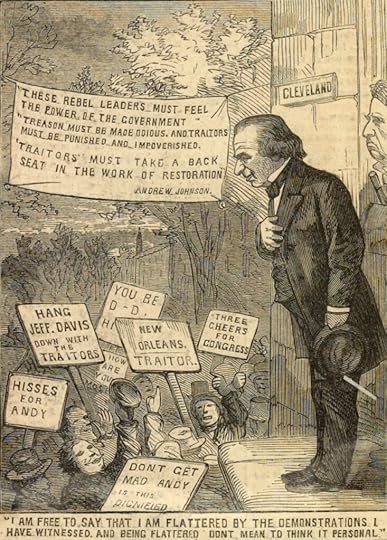

Thomas Nast’s rending of Andrew Johnson’s “Swing Around the Circle” stop in Cleveland. Library of Congress.

Thomas Nast’s rending of Andrew Johnson’s “Swing Around the Circle” stop in Cleveland. Library of Congress.Campaigning that year for reelection to the House (and simultaneously for his election to the U.S. Senate by the New York state legislature in January), Conkling left no doubt of his contempt for the deeply unpopular Johnson and his policies. He compared the president to French Emperor Louis Napoleon and called him “an angry man, dizzy with the elevation to which assassination has raised him.” When voters cast their ballots, Conkling predicted, “Andrew Johnson and his policy of arrogance and usurpation will be snapped like a willow-wand.”

Conkling didn’t stop there. Noting that the congressional Joint Committee of Reconstruction’s documentation of widespread violence against formerly enslaved Black Southerners foreshadowed racial violence in Memphis and New Orleans, he charged that Johnson’s policies dishonored Union war dead.

“Not satisfied with betraying the country by official action and by secret plotting; not satisfied with conniving at the robbery and murder of Unionists, and the exaltation and reward of traitors at the South, he comes now to buffet and slander the Union people of the North, and to blacken the memory of their dead,” Conkling thundered. His passionate rhetoric paid off. Conkling easily won reelection in November and, two months later, was elected to the U.S. Senate by the New York state legislature.

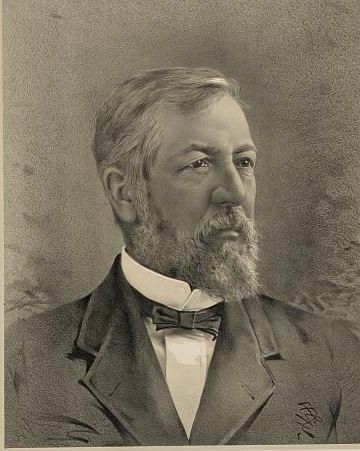

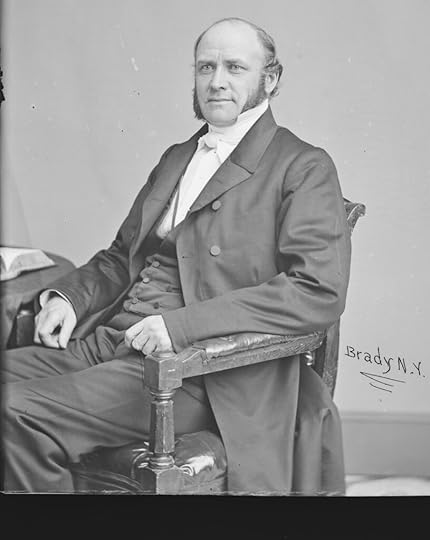

James G. Blaine. Library of Congress.

James G. Blaine. Library of Congress.Benjamin Butler: Blaine lacked Conkling’s taste for confrontation but — as he proved in 1866 when he mocked Conkling’s “grandiloquent swell” and “overpowering turkey-gobbler strut” — he could open fire on an opponent when antagonized.

Butler of Massachusetts was a radical Republican and former Union Army general reviled in the South for his treatment of civilians following the Union capture of New Orleans. So-called “liberal” Republicans opposed his approach to Reconstruction and loathed his support for monetary policies that favored paper money. He had plenty of enemies — and Blaine became one of them.

With terrorist violence against Black Southerners roiling the South in the early 1870s, Butler wanted the federal government to take vigorous action to ensure peace at the polls and protect civil rights. The general thought he had won the support of the House Republican caucus for legislation that would do so but was infuriated to discover that Blaine favored an alternative proposal. The Speaker’s plan — formation of a committee to investigate conditions in the former Confederacy — won passage in the House. Butler’s proposal never reached the floor.

Benjamin Butler. Library of Congress.

Benjamin Butler. Library of Congress.Furious, Butler circulated a letter to fellow Republicans denouncing Blaine and charging that the Speaker’s bill passed thanks to a backroom deal with pro-tariff Democrats. “Butler is more enraged to-night than during the proceedings to-day, if that were possible,” the Chicago Tribune reported. “He attributes his discomfiture not only to the connivance but to the actual assistance rendered by Speaker Blaine.”

Blaine reacted decisively and angrily. He stepped down from the Speaker’s chair — a dramatic parliamentary maneuver that signaled how seriously he regarded Butler’s allegations. He reminded the House that before the war Butler was a Democrat who supported the nomination of Jefferson Davis for president. Although Butler was an “astute lawyer,” his criticism showed that he was “extremely ignorant of the rules of the House.”

Most of all, Blaine took exception to what he believed was the insulting nature of Butler’s letter to the House. “As such I resent it. I denounce the letter in all its essential statements, and in all its misstatements, and in all its mean inferences and meaner innuendos,” the usually amiable Maine lawmaker declared.

Blaine’s friends in the congressional press gallery hailed his “passionate eloquence” the next morning. The Chicago Tribune said nothing like it had been heard in the House since Blaine’s famous retort to Conkling five years earlier.

President Ulysses S. Grant rendered Blaine’s investigative committee moot when he demanded congressional action to stem Southern violence. Congress obliged, and Grant came to Capitol Hill to sign what became known as the Ku Klux Klan Act. Nevertheless, Blaine’s colorful display of indignation signaled his eagerness to align with Republican moderates and liberals who loathed the Massachusetts radical and everything he stood for.

Thomas C. Platt: Conkling faced the greatest political crisis of his career with an ally who encouraged him to make a bad decision and made matters worse with a stunning lapse of judgment as Conkling fought for his political life.

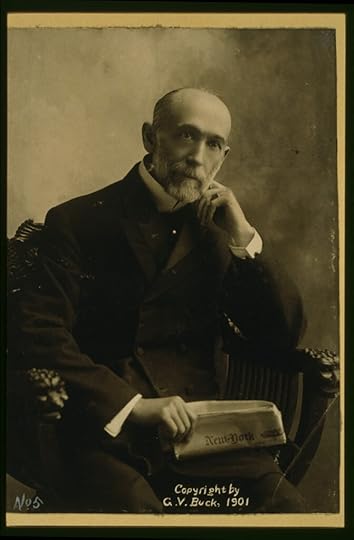

Thomas C. Platt in 1901. Library of Congress.

Thomas C. Platt in 1901. Library of Congress.A two-term member of the House, Platt came to the Senate in 1881 with a secret that, of revealed, would have put him at odds with Conkling. To win the support of dissident Republicans in Albany, Platt promised to vote for any nominations made by new president James A. Garfield, even if they were opposed by New York’s senior senator. That promise suddenly became problematic when Garfield nominated Conkling foe William Robertson to run the patronage-rich Port of New York — the basis of Conkling’s political power.

Faced with making good on his promise and antagonizing Conkling, Platt settled on a drastic course of action: He would resign his Senate seat only weeks after taking office. He shared the idea with Conkling, without disclosing his reasons for doing so. While it is unlikely that Platt talked the Conkling into resigning, he put the idea on the table. In the biggest mistake of his political career, Conkling followed suit. Conkling and Platt resigned May 16, 1881.

Weeks later, both changed their minds and resolved to win reelection to their Senate seats. But New York Republicans who had long chafed under Conkling’s imperious leadership balked at sending the man dubbed “Lord Roscoe” by the press back to Washington.

Their joint campaign took a severe jolt at the end of June when scandal engulfed Platt. Opponents spotted him entering his hotel room with a woman who was not his wife. Word of the apparent indiscretion spread and a stepladder that allowed his foes to peep into his room was procured. “The details of the scene are unfit for publication,” the Chicago Tribune sniffed. Platt “has been brought before the public gaze in a manner which has filled his friends with shame and humiliation.”

Platt dropped out of the race July 1, complicating Conkling’s bid for reelection. A day later, Charles Guiteau shot Garfield in a Washington train station. Widely blamed for creating the political tensions that stoked the fury of the deranged gunman, Conkling lost his bid to return to the Senate three weeks later.

Puck speculates about Conkling’s future after leaving the Senate.

Puck speculates about Conkling’s future after leaving the Senate.Rev. Samuel D. Burchard: The 1884 presidential campaign pitting Blaine against New York Democratic Gov. Grover Cleveland was nearing its end. Blaine had just completed an exhausting whistlestop campaign tour of New England, the Midwest, and western New York and prepared to receive what promised to be a relatively routine endorsement from a gathering of clergy on Oct. 29.

The spokesman for the ministers gathered at the Fifth Avenue Hotel in New York City was a Presbyterian cleric, Rev. Samuel Burchard. He greeted Blaine with standard boilerplate about how the clergy expected Blaine to “do honor” to the presidency (a not-so-veiled allusion to disclosures that Democrat Grover Cleveland had fathered a child out of wedlock). Burchard concluded with a pointed condemnation of Blaine’s foes. “We are Republicans, and don’t propose to leave our party and identify ourselves with the party whose antecedents have been rum, Romanism, and rebellion. We are loyal to the flag, and we are loyal to you.”

Rev. Samuel D. Burchard. National Portrait Gallery.

Rev. Samuel D. Burchard. National Portrait Gallery.Perhaps Blaine, worn out by the campaign, was too tired to respond. Perhaps, as many have suggested, he didn’t hear what Burchard said (although others did). Blaine himself confided to Supreme Court justice John Harlan that he chose to ignore the comment in the hopes that the press wouldn’t pick up on it. It was a huge mistake, and Democrats quickly attacked.

“It is amazing that a man as quick-witted as Blaine, accustomed to think on his feet and meet surprising changes in debate, should not have corrected the thing on the spot,” Democratic campaign operative Sen. Arthur Gorman marveled. Gorman made sure Burchard’s comments circulated widely.

Cleveland narrowly defeated Blaine by carrying New York state — the biggest electoral prize in the election — by 1,047 votes. In the years that followed, whispers that Blaine had been the victim of vote fraud in New York gained credence among some Republicans, although Blaine himself never challenged the results. Even those who suspected Democrats stole votes in New York acknowledged that the ill-considered alliteration of the enthusiastic Protestant minister was just as responsible for Blaine’s defeat in the Empire State. “I suppose also,” Massachusetts Republican George Frisbie Hoar conceded as he recounted charges of fraud at the polls, “that but for the utterances of a foolish clergyman named Burchard, Mr. Blaine’s majority in that State would have been so large that these frauds would have been ineffectual.”

My author’s website, RobertBMitchellbooks.com, is now live. Check it out for biographical information and links to my previous works about the Credit Mobilier scandal and Iowa Populist James B. Weaver.