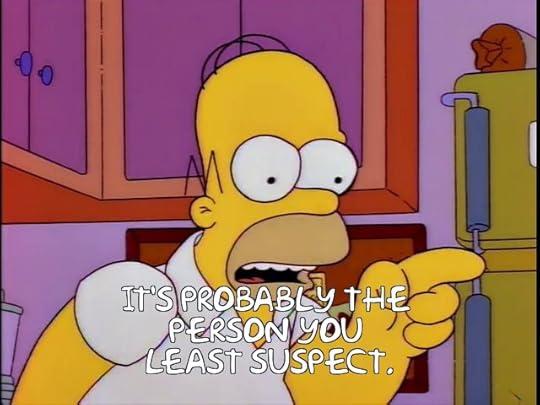

Expect it most when you expect it least

Homer Simpson: philosopher

Homer Simpson: philosopherYesterday, CrowdStrike released a Preliminary Post-Incident Review of the major outage that happened last week. I’m going to wait until the full post-incident review is released before I do any significant commentary, and I expect we’ll have to wait at least a month for that. But I did want to highlight one section of the doc from the section titled What Happened on July 19, 2024, emphasis mine

On July 19, 2024, two additional IPC Template Instances were deployed. Due to a bug in the Content Validator, one of the two Template Instances passed validation despite containing problematic content data.

Based on the testing performed before the initial deployment of the Template Type (on March 05, 2024), trust in the checks performed in the Content Validator, and previous successful IPC Template Instance deployments, these instances were deployed into production.

And now, let’s reach way back into the distant past of three weeks ago, when the The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) posted an executive summary of a major outage, which I blogged about at the time. Here’s the part I want to call attention to, once again, emphasis mine.

Rogers had initially assessed the risk of this seven-phased process as “High.” However, as changes in prior phases were completed successfully, the risk assessment algorithm downgraded the risk level for the sixth phase of the configuration change to “Low” risk, including the change that caused the July 2022 outage.

In both cases, the engineers had built up confidence over time that the types of production changes they were making were low risk.

When we’re doing something new with a technology, we tend to be much more careful with it, it’s riskier, we’re shaking things out. But, over time, after there haven’t been any issues, we start to gain more trust in the tech, confident that it’s a reliable technology. Our internal perception of the risk adjusts based on our experience, and we come to believe that the risks of these sorts of changes are low. Any organization who concentrates their reliability efforts on action items in the wake of an incident, rather than focusing on the normal work that doesn’t result in incidents, is implicit making this type of claim. The squeaky incident gets the reliability grease. And, indeed, it’s rational to allocate your reliability effort based on your perception of risk. Any change can break us, but we can’t treat every change the same. How could it be otherwise?

The challenge for us is that large incidents are not always preceded by smaller ones, which means that there may be risks in your system that haven’t manifested as minor outages. I think these types of risks are the most dangerous ones of all, precisely because they’re much harder for the organization to see. How are you going to prioritize doing the availability work for a problem that hasn’t bitten you yet, when your smaller incidents demonstrate that you have been bitten by so many other problems?

This means that someone has to hunt for weak signals of risk and advocate for doing the kind of reliability work where there isn’t a pattern of incidents you can point to as justification. The big ones often don’t look like the small ones, and sometimes the only signal you get in advance is a still, small sound.