Losing the South “to save the North”

In his history of the post-Civil War South, Mississippi Republican John R. Lynch recounted the thinking that drove Republicans to back away from their support for Reconstruction.

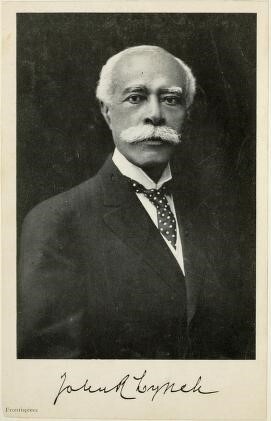

He began life in slavery and served in Congress. He knew James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling and President Ulysses S. Grant. In the early 20th century, when conventional wisdom dismissed the post-war Republican plan to rebuild the political order of the South as hopelessly flawed, he wrote a thoughtful and illuminating rebuttal, The Facts of Reconstruction, published in 1913.

John R. Lynch was one of the most remarkable political figures of the Gilded Age. Born in Louisiana to a white father and Black mother, Lynch and his mother were sold to a Mississippi enslaver following his father’s death, according to Maurine Christopher’s Black Americans in Congress. After the Union Army liberated Natchez during the Civil War, Lynch taught himself to read, worked as a photographer, attended night school, and became an active Republican, Christopher wrote.

John R. Lynch, from The Facts of Reconstruction.

John R. Lynch, from The Facts of Reconstruction.Lynch served four years in the Mississippi legislature and was elected Speaker before coming to Washington after winning a seat in the House in 1872. A skilled orator and writer, he was re-elected in 1874 but defeated two years later. Lynch returned to the House for two more years after winning an election in 1880. Four years later he was elected temporary chairman of the Republican National Convention in Chicago after he was nominated by Theodore Roosevelt. In 1896, Lynch was admitted to the Mississippi Bar after studying to become a lawyer, according to his congressional biography.

His first two terms in Congress provided a unique perspective as congressional Republicans — and Grant — began to move away from wholehearted support for the multi-racial Reconstruction state governments of the South.

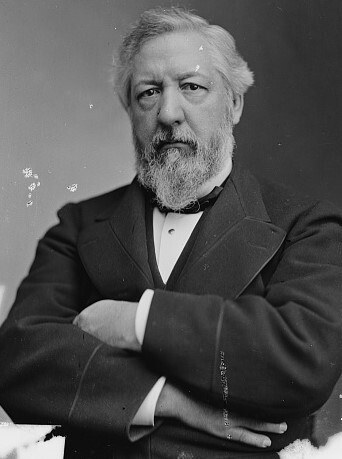

In 1874, with the economic devastation caused by the Panic of 1873 still top of mind for millions of voters, Democrats rode a wave of popular discontent with Republican economic policies to take control of the House for the first time since 1858. “The victory in the presidential election of 1872 had been so sweeping,” James G. Blaine wrote in the second volume of Twenty Years of Congress, “that it seemed that no re-action were possible for years to come.”

The midterm elections of 1874 demonstrated that the aftermath of the war no longer ranked as the primary concern for millions of Northern voters, who were now more worried about keeping a roof over their heads than conditions in the former Confederacy. Northern Republicans took note and adjusted accordingly, Lynch concluded. The Republican Party in the South, Lynch wrote, was “young, weak, and comparatively helpless,” he wrote. It continued to need the support of its Northern “parent,” which had been “carried away from the battlefield seriously wounded and unable to administer to the wants of its Southern offspring.”

James G. Blaine. Library of Congress.

James G. Blaine. Library of Congress.What that meant quickly became clear. In January 1875, federal troops were dispatched to the Louisiana state legislature to prevent Democrats from violently taking control. Outraged Northern public opinion signaled that support for Reconstruction was in rapid decline. In March, during the closing hours of the Forty-Third Congress, the House debated legislation that would allow the prosecution of election violence in federal courts and the president to suspend habeas corpus in areas plagued by terrorism. Blaine, in one of his last acts as House Speaker, allowed debate on the bill to drag on until it was no longer possible for the measure to get on the Senate calendar. The House passed the bill, but with time running out and Democrats poised to take control of the House, it was dead.

Lynch was stunned and sought an explanation.

“In my judgment, if that bill had become law the defeat of the Republican Party throughout the country would have been a foregone conclusion,” Blaine said. “In my opinion it was better to lose the South and save the North, than to try through such legislation to save the South, and thus lose both North and South.”

Blaine wasn’t the only Republican thinking that way.

“White-line” Democrats in Mississippi launched a campaign of terror directed at Black Republicans during the during the 1875 state election campaign in Mississippi. “Democratic clubs were organized in all parts of the state, and the able-bodied members were also organized into military companies with the best arms that could be procured in the country,” a Senate report would later find. Riots in Vicksburg and Clinton “were the result of a special purpose on the part of the Democrats to break up the meetings of Republicans, to destroy the leaders, and to inaugurate an era of terror, not only in those counties but throughout the state, which would deter Republicans, and particularly the Negroes, from organizing or attending meetings, and especially deter them from the free exercise of the right to vote on the day of the election.”

As the violence intensified, Republican Gov. Adelbart Ames asked for federal assistance in assuring peace at the polls. To the surprise and disappointment of Ames and Lynch, the Grant administration did nothing.

“In my opinion it was better to lose the South and save the North, than to try through such legislation to save the South, and thus lose both North and South.”

James G. Blaine

After the election, Lynch asked Grant why he withheld assistance. The president said he had drawn up orders for the deployment of federal troops but before it was issued a delegation of Ohio Republicans predicted that it could lead to the party’s defeat in fall elections. Grant said the Ohio Republicans warned “in the most emphatic way that if the requisition of Governor Ames were honored, the Democrats would not only carry Mississippi — a state which would be lost to Republicans in any event — but that Democratic success in Ohio would be an assured fact.”

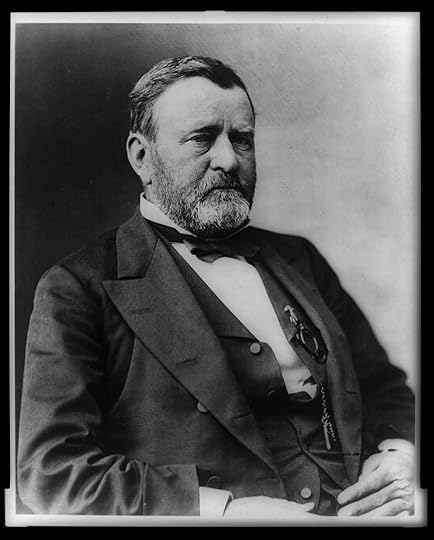

President Ulysses S. Grant. Library of Congress.

President Ulysses S. Grant. Library of Congress.Grant, Lynch wrote, said he regretted his decision.

“I should not have yielded” to the Ohio Republicans, he told Lynch. “I believed at the time I was making a grave mistake. But as presented, it was duty on one side and party obligation on the other. Between the two I hesitated but finally yielded to what was believed to be party obligation. If a mistake was made, it was one of the head and not one of the heart.”

As recalled by Lynch, Grant continued the discussion by sharing his foreboding about what was ahead.

Grant said he believed one consequence of the war was the creation of “national citizenship” that allowed the federal government to act “to protect its own citizens against domestic and personal violence” whenever states failed to do so. “But there seem to be a number of leading and influential men in the Republican Party who take a different view of these matters,” Grant added. “What you have passed through in the state of Mississippi is only the beginning of what is sure to follow. I do not wish to create unnecessary alarm, nor to be looked upon as a prophet of evil, but it is impossible for me to close my eyes in the face of things that are as plain to me as the noonday sun.”

“It is needless to say,” Lynch wrote, “that I was deeply interested in the president’s eloquent and prophetic talk which subsequent events have more than fully verified.”

*****

Lynch is among the personalities featured in my latest book, The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge, coming this fall from Edinborough Press. My other books on the politics, scandals and personalities of the Gilded Age are available at amazon.com: