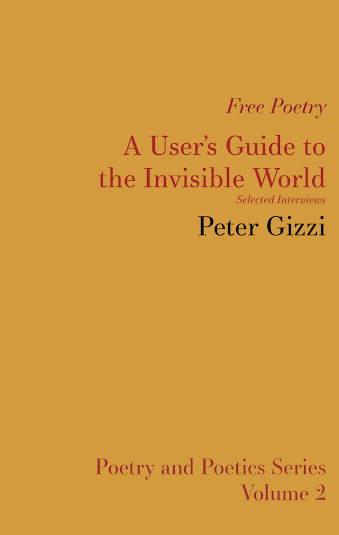

Peter Gizzi, A User’s Guide to the Invisible World: Selected Interviews, ed. Zoe Tuck

Though I’ve given yousome of my personal backdrop of the periods in which I composed some of mywork, it’s not that I narrate my biography in any of these poems. I don’t reallywrite about my life. I write out of my life and where I am at agiven moment of thinking and feeling. I mean to say, you don’t need to know mystory to get the work, i.e., to fully engage with it. I’d like to call it a feelingintellect. I feel it’s more useful, and more honest, to interrogate rather thanexplain away an ungovernable, complex emotional state. I favor sensation overautobiography. It’s like I’m an ethnographer of my nervous system. (YALE LITERARYMAGAZINE—2020 “NATIVE IN HIS OWN TONGUE: AN INTERVIEW WITH POET PETER GIZZI”JESSE GODINE)

I’mappreciating the insight into American poet and editor Peter Gizzi’s writingand thinking through

A User’s Guide to the Invisible World: Selected Interviews

(Boise ID: Free Poetry Press, 2021), edited with an introductionby Zoe Tuck. Gizzi is the author of numerous books and chapbooks, including

Fierce Elegy

(Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2023) [see my review of such here],

Now It’s Dark

(Wesleyan, 2020) [see my review of such here], Sky Burial: New and Selected Poems (Carcanet, UK 2020), Archeophonics(Wesleyan, 2016),

In Defense of Nothing: Selected Poems 1987-2011

(Wesleyan, 2014),

Threshold Songs

(Wesleyan, 2011),

TheOuternationale

(Wesleyan, 2007) [see my review of such here],

SomeValues of Landscape and Weather

(Wesleyan, 2003),

Artificial Heart

(Burning Deck, 1998), and Periplum (Avec Books, 1992), as well asco-editor (with Kevin Killian) of

my vocabulary did this to me: The Collected Poetry of Jack Spicer

(Wesleyan University Press, 2008) [see my review of such here]. Moving through his website, it is frustrating to bereminded how much of his work I’m missing (I’ve reviewed everything of his I’veseen, if that tells you anything), but interesting to realize that Wesleyan UniversityPress published

In the Air: Essays on the Poetry of Peter Gizzi

(2018),a further title I’d be interested to get my hands on, especially after goingthrough these interviews.

I’mappreciating the insight into American poet and editor Peter Gizzi’s writingand thinking through

A User’s Guide to the Invisible World: Selected Interviews

(Boise ID: Free Poetry Press, 2021), edited with an introductionby Zoe Tuck. Gizzi is the author of numerous books and chapbooks, including

Fierce Elegy

(Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2023) [see my review of such here],

Now It’s Dark

(Wesleyan, 2020) [see my review of such here], Sky Burial: New and Selected Poems (Carcanet, UK 2020), Archeophonics(Wesleyan, 2016),

In Defense of Nothing: Selected Poems 1987-2011

(Wesleyan, 2014),

Threshold Songs

(Wesleyan, 2011),

TheOuternationale

(Wesleyan, 2007) [see my review of such here],

SomeValues of Landscape and Weather

(Wesleyan, 2003),

Artificial Heart

(Burning Deck, 1998), and Periplum (Avec Books, 1992), as well asco-editor (with Kevin Killian) of

my vocabulary did this to me: The Collected Poetry of Jack Spicer

(Wesleyan University Press, 2008) [see my review of such here]. Moving through his website, it is frustrating to bereminded how much of his work I’m missing (I’ve reviewed everything of his I’veseen, if that tells you anything), but interesting to realize that Wesleyan UniversityPress published

In the Air: Essays on the Poetry of Peter Gizzi

(2018),a further title I’d be interested to get my hands on, especially after goingthrough these interviews.I’mintrigued with what American poet and editor Martin Corless-Smith is doing withthis venture, the handful of titles he’s published to date through the Free Poetry’s “Poetry and Poetics Series” [see my review of Cole Swensen’s And AndAnd (2022) from the same series here], apparently accepting manuscripts andpitches on a case-by-case basis. A User’s Guide to the Invisible World: SelectedInterviews, produced as volume two in this ongoing series, compiles nine previouslypublished interviews with Peter Gizzi from 2003 to 2021, from The Paris Review,Poetry Foundation, jubilat and Rain Taxi, conducted by writers,critics and poets such as Ben Lerner, Aaron Kunin, Levi Rubeck, Matthew Holmanand Anthony Caleshu. As editor Tuck writes as part of their introduction: “Whyinterviews? Biography can too easily become hagiography (Gizzi would be the firstto insist that he’s a person, not a saint), and memoir carries with it the impulseto smooth life’s unruliness into a single consistent narrative. If readings arepoetry’s official ritual, interviews are the cigarette outside: intimate andunrehearsed. What’s more, the interview is a relational form. And the variousinterlocutors in this collection—a precocious undergrad, notablecontemporaries, life-long friends, people from places where Gizzi has traveled—callforth distinct facets of his life and work.” There is something reallyinteresting about hearing the author’s thoughts in their own words, as well as,as Tuck suggests, a directed thinking through not only conversation, but multipleconversations. The portrait that emerges of Gizzi is one that shouldn’t surpriseanyone familiar with his work, providing a deeply thoughtful and engaged readerand thinker, one who has read widely, is open to new influences and ideas, andholds firm to his influences, as well as providing curious echoes betweeninterviews (given the range of dates is within a particular boundary of sixteenyears, that certainly makes sense). As Gizzi responds as part of an interview conductedby Ben Lerner:

As Ted Berrigan said, “I writethe old-fashioned way, one word after another” or, to quote Pound, “put on atimely vigor.” As long as there is soldiery, there will be poets: “I sing ofarms and the man,” Virgil begins his tale of the west; sadly, the relationbetween war and song is a venerable tradition. I own it. There is no easy “app”to the muses. I suspected that your original question about the “perils ofsinging” was connected to the many discussions, debates, and attacks on thelyric as a substantial form of thinking (I almost wrote “thinking”). Why shouldI apologize for, or give up on, one of the most flexible and dynamic forms ofpoetry? So I can download my work? I mean, what do they call the guy whograduates last in his class at a fancy med school? Doctor. It’s scary. But it’sthe same for poetic practice. And as is the case with all disciplines, it’salways a question of ambition, of how well it’s done, right? Like every goodpoet before me, I accept my responsibility to my vocation.