Simina Banu, I Will Get Up Off Of

this monobloc but I fear Iam becoming experimental with my attempts. Last night I tried to hoist myselfup by gripping onto bananas taped all over the walls. They couldn’t bear theweight of something: me? Sometimes the tape would peel the paint right off thewall, revealing a horrifying yellow undercoat, and aother times the bananawould just split, leaving me banana-handed but utterly seated.

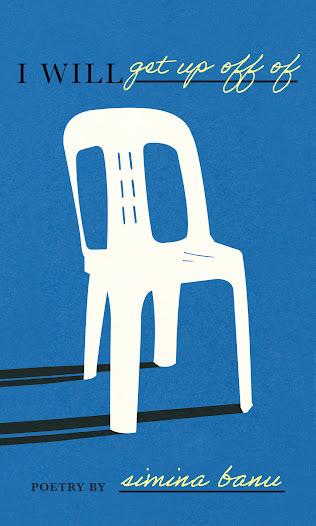

Thesecond full-length collection by Montreal poet Simina Banu, following

POP

(Toronto ON: Coach House Books, 2020) [see my review of such here], is

I Will Get Up Off Of

(Coach House Books, 2024), a book-length suite akin to a deckof cards, working through layers of depression, regression and response. As theback cover writes: “How does anyone leave a chair? There are so many musclesinvolved – so many tarot cards, coats, meds, McNuggets, and memes. In thisbook, poems are attempts and failures at movement as the speaker navigates heranxiety and depression in whatever way she can, looking for hope from socialworkers on Zoom, wellness influencers, and psychics alike. Eventually, thepoems explode in frustration, splintering into various art forms as attempts atexpression become more and more desperate.” From the cluster of lyricexplorations of her full-length debut, Banu shifts into a structure of proselyrics that cohere into a book-length structure, the first page of which openswith a single fragment—“I will get up off of”—before the following pagefurthers that thought, leaving the space where the prior page, that priorphrase, had left off:

Thesecond full-length collection by Montreal poet Simina Banu, following

POP

(Toronto ON: Coach House Books, 2020) [see my review of such here], is

I Will Get Up Off Of

(Coach House Books, 2024), a book-length suite akin to a deckof cards, working through layers of depression, regression and response. As theback cover writes: “How does anyone leave a chair? There are so many musclesinvolved – so many tarot cards, coats, meds, McNuggets, and memes. In thisbook, poems are attempts and failures at movement as the speaker navigates heranxiety and depression in whatever way she can, looking for hope from socialworkers on Zoom, wellness influencers, and psychics alike. Eventually, thepoems explode in frustration, splintering into various art forms as attempts atexpression become more and more desperate.” From the cluster of lyricexplorations of her full-length debut, Banu shifts into a structure of proselyrics that cohere into a book-length structure, the first page of which openswith a single fragment—“I will get up off of”—before the following pagefurthers that thought, leaving the space where the prior page, that priorphrase, had left off:this monobloc butI’ve been sentenced and now I am running through a field of memes. I treadsoftly, and they bite at my feet, relatably, godless. The memes are mycompanions, and I want to tell them how I’ve felt these days, because the memeswill understand. They’ve been here too. They’ve felt like this, just like this.I know because they talk about their psychotherapists and their debts and theirSSRIs and their exes and their microwaves and their possums. I trip. The memesencircle me, mouths agape like baby birds, and I feed them flesh from my eyes,and I feel loved.

Composedin a sequence of prose blocks, there is something less of the prose poem to thisstretch of pieces than a poetry book’s-worth of prose extensions across thelyric sentence, each broken up into blocks, each returning to that same GroundhogDay moment. “this monobloc but Goya’s dog drowned in mud.” she writes, afew pages in. “It’s true the dog gazed upward, but she was looking at mud, andguess what, the mud wasn’t looking at her. If we want to be accurate, she waslooking at oil, she was oil, and everyone was plastered. Me too, over and overand over: the oil fills my stomach, and the mud fills me.” There is somethingcompelling in how Banu rhythmically returns each lyric opening to “thismonobloc,” offering book title as the presumed opening phrase of each poem, perpetuallyreturning to the beginning, to begin again, offering a tethered andunsettlingly stressed variation on Robert Kroetsch’s structure of composing thelong poem; by continually returning to the beginning, one can keep goingindefinitely, after all. And yet, Banu’s seemingly-unbreakable narrative tetheris entirely the crux of the problem her narrator wishes to address, reducingthe complexities of depression and anxiety down to the simplest, anddeceptively so, of questions, asking: How does one get up from a chair?