Keep Your Eyes on Your Own Plate (Guest Post by Linda B. Davis)

Think about the meals you’ve eaten in the past week.Probably at least half of them were eaten with other people, because eating isa familial and social activity. And when we share a meal with others, or eveneat in close proximity to others in a restaurant or cafeteria, we have a close-upview of the food that is sitting on someone else’s plate.

What people eat and don’t eat is based on all sorts offactors—including personal preferences, cultural heritage, religious beliefs,and health concerns. We’re all accustomed to hearing I’m vegan. I’mgluten-free. I’m lactose-intolerant. I keep kosher. I’mdoing keto. I have food allergies…and we generally accept and accommodatethese needs without question.

But what about picky eaters? We tend to be a lot lesstolerant when it comes to a picky eater, whether that picky eater is an adultor a child. We don’t consider picky eating to be legitimate. In fact, we tendto treat picky eaters as though they are difficult, stubborn, unsophisticated,or overindulged.

And we couldn’t be more wrong.

The first picky eater I knew was my own nephew. Whatseemed to be a manageable inconvenience when he was young became increasinglycomplicated when he started middle school. Like most middle schoolers, hisworld was expanding to include all sorts of new social experiences away fromhome—and most of those experiences involved food. At a time when kids are typicallyfocused on trying to fit in, his extremely limited diet made him stand out, andhe was on the receiving end of unwanted attention from his peers and adults.

I didn’t understand his situation, and I hate to admitit, but sometimes I was a bit judgmental. And I should have known better,especially since I have master’s degrees in developmental psychology and socialwork. When I finally saw the acronym ARFID (Avoidant/Restrictive Food IntakeDisorder) I realized I had a lot to learn.

ARFID, a relatively new diagnosis, is an eatingdisorder often characterized as extreme picky eating, but it is actually quite seriousand can cause significant medical, social, and self-esteem issues in kids andadults. ARFID is described as a lack of interest in eating or avoidance of foodbased on its sensory characteristics including texture, smell, color. ARFID issometimes defined as a food-related phobia. Some people living with ARFID simplysay that most food doesn’t seem like something they could put in their mouthand eat.

Consequently, people with ARFID have a very smallrepertoire of foods that feel “safe” to eat, and those foods are oftenprocessed or fast foods because that is the kind of food that is the sameevery single time. (Think goldfish crackers, McDonald’s French fries, orDomino’s cheese pizza compared to bananas, homemade macaroni and cheese, orhamburgers, which can differ considerably depending on the chef or the recipe.)Unfortunately, processed/fast foods are also considered unhealthy, and peoplewith ARFID are often shamed for eating what is commonly referred to as “junkfood.” What many people don’t understand is that people with ARFID do not chooseto eat only “safe” foods—these are the only foods they can eat.

I was beginning to recognize that for kids with ARFID,social gatherings of any sort can be overwhelming and anxiety producing—Can youthink of a special event you’ve attended recently that did not include ameal or at least a slice of birthday cake? And bigger or more formal functions canbe even more catastrophic for a kid with ARFID because celebrations andholidays are rooted in tradition and traditional foods, creating a real recipefor disaster. (Imagine a Thanksgiving dinner featuring cornbread stuffing,pumpkin pie, and creamed spinach. Now imagine how it might feel for a kid withARFID to sit at the table with an empty plate or an untouched plate of food andthe things even well-meaning relatives might say.)

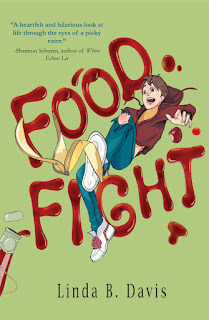

My research led me to quite a bit of informationtailored to parents of ARFID kids, but I wasn’t finding anything created for thekids themselves. This is what led me to write Food Fight, a middle gradenovel about an eleven-year-old boy named Ben who is living with ARFID. I wantedto explore the social complications ARFID can cause and its impact onself-esteem, self-confidence, and relationships with peers and parents. My hopeis that kids living with ARFID will see themselves on the page and possiblyfeel less alone, and readers who are unfamiliar with ARFID will relate to acharacter who struggles to accept himself and be accepted by his peers.Although ARFID is a relatively rare condition, the types of challenges itpresents are universal in the world of middle graders as they confront thenever-ending question of How do I fit in?

Food Fightalso features more typical middle grade fare such as first crushes, bullying,friendship changes, unexpected allies, and an overnight class trip, and all ofthose potentially challenging experiences are even trickier for Ben when foodis in the mix—and it’s always in the mix for Ben and his peers as they doregular middle school things like share fries at the mall, walk into town forice cream, roast marshmallows on a class trip, and eat pizza at their firstboy/girl party.

Ultimately, I hope Food Fight encourages peopleto react to picky eating and ARFID with empathy rather than judgment. I thinkwe’re all better off when we keep our eyes on our own plates.

Bio

Linda B.Davis holds master's degrees in social work and developmental psychology. As asocial worker in a community mental health setting, Linda became passionateabout the need for accurate and accessible mental health information in children'sliterature. Linda lives outside Chicago and enjoys traveling with her family,buying more books than she can possibly read, and maintaining her Little FreeLibrary. Her middle grade novel, Food Fight, is the story of anovernight class trip that becomes a survival mission for an eleven-year-old boywith ARFID. Food Fight will be released by Regal HousePublishing on June 27, 2023.