In Praise of the Paragraph!

Pilcrow: Pilcrow symbol.

Pilcrow: Pilcrow symbol. Source at Image:Pilcrow.svg

One of the most important punctuation marks goes aboutquietly, doing its job without any notice or fanfare. It’s also the oldestof all punctuation marks, dating back to ancient Greece. It’s used a thousandtimes in every book. As Noah Lukeman (A Dash of Style: The Art and Mastery ofPunctuation, 2006) suggests, “…it alone can make or break a work.”

What is it?

The paragraph break!

As Lukeman reminds us, there is an underlying rhythm to alltext. Sentences crash and fall like thewaves of the sea. Indeed, punctuation is the music of language. And just as amelody inspires certain responses from a listener, so it goes with sentences,and by extension, punctuation. Note: I’m notspeaking of grammatically correct sentences.

“By controlling the speed of a text, punctuation dictateshow [the story] should be read.”

Once upon a time, reading was hard work. There was nopunctuation, no white-space, no lower case letters. There was nothing toindicate when one thought ended and the next one began.

The pilcrow was the first punctuation mark. The wordoriginated from the Greek paragraphos, (para=beside and graphos=towrite). This led to the Old French, paragraph. This evolvedinto pelagraphe, and then to pelegreffe. Middle Englishtransformed it into pylcrafte, and finally to pilcrow.

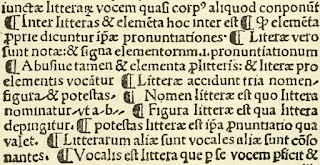

Around 200 AD, paragraphs were very loosely understood as achange in topic, speaker, or stanza. But there was no consistency in thesemarkings. Initially, some used the letter K, for Kaput, which isLatin for head. By the 12th century, scribes began using C,for Capitulum, Latin for little head or chapter. This C evolvedbecause of inconsistencies in handwriting. By late medieval times, the pilcrowwas a very elaborate decoration in bright red ink inserted in between shapelessparagraphs.

Villanova, Rudimenta Grammaticæ. Published 1500 in Valencia (Spain)..

Villanova, Rudimenta Grammaticæ. Published 1500 in Valencia (Spain).. Licensed under Public Domain

As printing technology improved, and whitespace was deemedvaluable in the reading process, pilcrows were dropped down to indicate a newline. Eventually the pilcrows were abandoned, and the paragraph indent wasborn. It wasn’t until the mid-1800s that a standard method was devised to helporganize paragraphs. Alexander Bain introduced the modern paragraph in 1866,defining it as a single unit of thought, and stressing the importance of anexplicit topic sentence.

Just as a period divides sentences, a paragraph divides groups of sentences.But as the period is often hailed as the backbone of punctuation, the paragraphbreak is largely ignored.

The primary purpose of a paragraph is to define a theme, but there are nostandard rules that dictate how that process plays out. Paragraphs tend to beorganic, subject to the writer’s idiosyncrasies.

In a perfect world, a paragraph has a beginning, the main point stated in anexplicit topic sentence. It has a middle, in which the writer elaborates onthis one main point. And it has an ending, which wraps the entire package in aneat bow.

But the world isn’t perfect. Sometimes the writer places the topic sentence asthe last line of a paragraph, playing “gotcha” like a punchline of a joke.Sometimes the topic sentence is a mere whisper, implied in the action. And thenthere’s the prankster, who places the topic sentence in the middle of aparagraph. Blink and you miss it.

Further complicating the process, there is no designatedlength that defines a paragraph. Some insist that a paragraph be fivesentences, even when the concept is so complex, it demands more explanation.They call this being succinct, but when I ask them for clarification, it takesthem several minutes to explain one sentence. I remind them, succinct does notmean short. Succinct means precise. Meanwhile, others go to the oppositeextreme. A paragraph expands across one – and sometimes more – pages. Ideas trample over each other,undistinguished from each another, in one stampeding info dump. Both of thesewriter types reflect a common issue: they don’t understand, and therefore arenot connected to, their own ideas. As Lukeman states, messy breaks reveal messythinking.

The long and short of it (and all puns intended), paragraphs affect pacing,showing the reader how to approach the text. This is especially true infiction.

Short paragraphs tend to be action-oriented, focusing on moving theplot forward. Long paragraphs slow the action down, and tend to be reflective,either setting the stage for the next chase or revealing character. Too manyshort paragraphs strung together can wear the reader out. Too many longparagraphs put readers to sleep. But with the right combination, the paragraph fades into the background, allowing the reader to experience the action.

For example, can you hear the drum beat -- illustrated by the paragraph breaks -- in this passage (as the Ninth Infantry of the Confederate Army starts marching across the cornfield in what becomes the ill-fated Pickett’s Charge) from my book, Girls of Gettysburg (Holiday House, 2014)?

Bayonets glistening in the hot sun, the wall of men stepped off the rise in perfect order. The cannoneers cheered as the soldiers moved through the artillery line, into the open fields.The line had advanced less than two hundred yards when the Federals sent shell after shall howling into their midst.

Boom! Boom! Boom!

The shells exploded, leaving holes where the earth had been. Shells pummeled the marching men. As one man fell in the front of the line, another stepped up to take his place. Smoke billowed into a curtain of white, thick and heavy as fog, stalking them across the field.

Still they marched on. They held their fire, waiting for the order.

Boom! A riderless horse, wide-eyed and bloodied, emerged from the cloud of smoke. It screamed in panic as another shell exploded.

Boom! All around lay the dead and dying. There seemed more dead than living now. Men fell legless, headless, armless, black with burns and red with blood.

Boom! They very earth shook with the terrible hellfire.

Happy [Paragraph] Writing!

-- Bobbi Miller