Bob’s Bridge Game

The problem with games such as snooker, pool, billiards, and bagatelle, popular as they may be, is that a full-size table together with sufficient room to enable the players to address their shots from any point means that you need a considerable amount of space to play them. Only the well-off were able to allocate a separate room to which the men could retire after dinner to play a game. The lower orders had to resort to playing in club premises established for the purpose or on smaller versions of the tables in public houses and clubs. As a consequence, opportunities to play at fairs and fetes on outdoor tables were eagerly seized upon.

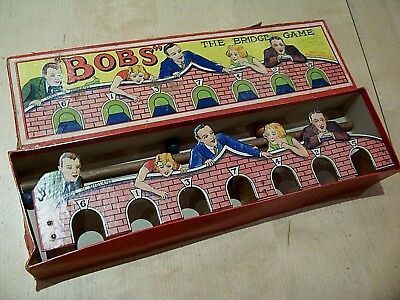

Indoor games manufacturers realised that there was a ready market for an indoor version of a cue and ball game, if they could only develop one that was relatively simple and space efficient. One such that emerged in the early 20th century was Bob’s Bridge Game, which, if the labelling on the top of the box in which it came is to be believed, was “a popular colonial pastime for any number of players”. It is not clear whether this meant that the game originated from one of the outposts of the British Empire or whether those sent to some far-flung outpost of the empire whiled away their hours playing it.

On opening the box, the players would find a wooden bridge with a number of arches, usually between seven and nine, cut into it. Above each arch was painted a number which represented the number of points you scored if you spotted a ball through it. The bridge had two side flaps which allowed it to stand up. There was also a cue, in two parts which fitted together, usually with red trim and a blue end. To complete the equipment supplied there were seven balls, one of which was red while the others were uncoloured. Regrettably, in early versions of the game the balls were made of ivory.

The game was simplicity itself. You would place the bridge at one end of the table with the side showing the numbered arches facing the players. The red ball would then be place in the centre of the table, about six inches away from the bridge. Taking the cue, a player would strike one of the uncoloured balls with the intention of striking the red ball or any other ball in play and placing it through one of the arches. If the player failed to put a ball through an arch, the ball was left in play and the next player took their shot.

If an uncoloured ball went through an arch, the player scored the number of points allotted to the arch. If they managed to put the red ball through, their score was doubled. If their ball went through an arch without striking another ball, then the points allocated to the arch were deducted from their score. The winner was the one who had the most points when only one ball remained in play.

I wonder how much damage was caused when the balls shot through the arch and fell off the end of the table. A fourth piece of wood, attached to the flaps so that it made an enclosed area, would not only have given the structure extra rigidity but also would have held the balls. This simple solution didn’t seem to strike the manufacturers, probably because it would have made the structure unwieldy for packing into a box of a size that would appeal to shopkeepers.