Book Review: Not All Fairy Tales Have Happy Endings: The Rise and Fall of Sierra On-Line as Told by the Ultimate Insider by Ken

I’m going to do that thing that lots of people, myself included, really don’t like. You know, that journalistic habit of inserting themselves into the thing they are reviewing or talking about and making the discussion about them and not the work in question. But I can’t help myself because (a) this is my personal blog, and (b) the topic of this book is incredibly near and dear to me.

You see, Sierra games were a huge part of my childhood, and dare I say it, an influence on me.

When you saw this logo come up on your computer and heard that jingle, you knew you were in for something good.

When you saw this logo come up on your computer and heard that jingle, you knew you were in for something good.My dear, late grandfather always loved technology. In the mid-1980s he hopped on board the home computer bandwagon and learned DOS like a pro. My uncle, who is considerably younger than my father, was still living with my grandparents at the time, and he bought some games for this system, including Police Quest, Space Quest, and King’s Quest III.

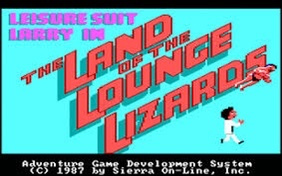

He also bought Leisure Suit Larry in the Land of the Lounge Lizards when that game came out. Needless to say, once my parents figured out what that game was about, they were not pleased.

Yes, Larry is chasing a blow-up doll. Yes, this happens in the game. No, I’m not going to tell you how Larry loses it.

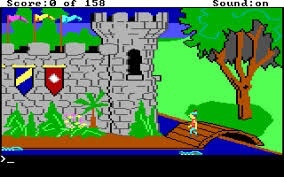

Yes, Larry is chasing a blow-up doll. Yes, this happens in the game. No, I’m not going to tell you how Larry loses it.In any event, these games were mind-blowing to a five-year-old me and my six-year-old brother. Faster watching my uncle and grandfather show our father King’s Quest III–and cracking up as dad typed in some decidedly not-safe-for-work commands just to see what the game would say–my brother and I asked Papou if we could try. He, of course, said yes, and we were on our way to adventure-gaming heaven.

If you’re not familiar with Sierra’s graphical adventure games, they were the outgrowth of the old text-based adventures from the late 1970s and early 1980s. Text adventures are how they sound: you are given a textual description of the room you are in and you type commands into a parser like “Look room,” “Get shovel,” “Go north,” and so on, to accomplish some objective. Sierra’s big innovation upon their founding in 1979 was adding graphics to a text adventure, thereby creating the first graphical text adventure called Mystery House.

The first screen of Mystery House. Groundbreaking at the time.

The first screen of Mystery House. Groundbreaking at the time.The graphics were crude, but Mystery House was a resounding success. More followed. Sierra would then add color. Amazing! But the biggest, most impactful innovation was the addition of 3-D graphics and a character you could move throughout an imaginative landscape.

To say Sierra was the king of computer games in the 1980s is a serious understatement. The amazing thing is that the company was the brainchild of a married couple in their early 20s: Ken and Roberta Williams.

Roberta and Ken Williams

Roberta and Ken WilliamsKen learned computers, and Roberta had an imagination that spurred Ken to do unheard of things with them. When Roberta played one of the first big text adventures, Colossal Cave Adventure, it was she who got Ken to add graphics. She later got Ken to figure out how to add color–and Ken later wrote a book about creating graphics for the Apple ][. And Roberta kept coming up with new narrative possibilities for home computers, which eventually led to her asking “Why can’t we create a little guy that can walk around the screen and actually interact with things so we can show the player what they’re doing when they type commands instead of just telling them?”

Ken was the brains, and Roberta was the heart. Ken was the business guy and Roberta was the imagination woman. To say that Roberta is one of the most influential women in the history of gaming is another understatement. And to say that Ken was one of the most influential men is . . . well, you get the idea.

These games were so fun because of the care and passion that went into them. I’ll get into why this is later, but whether you’re playing the fairy-tale inspired fantasies of King’s Quest, the loving sci-fi spoofs of Space Quest, the raunchy though light-hearted Leisure Suit Larry series, the by-the-book procedurals of Police Quest, the dark and gothic Gabriel Knight supernatural mysteries, the historical Conquest duology, or the adventure/RPG hybrid Quest for Glory games, you were getting a product that was a true labor of love. From the puzzles and the plots to the graphics and the music, Sierra was always pushing the boundaries of the day’s technology while making sure the games were fun.

King’s Quest I

King’s Quest I

Sierra did more than just adventure games, as you’ll find out in Not All Fairy Tales Have Happy Endings. But these games were what put them on the map. Personally, as a little kid who was already a voracious reader, these games taught me how to type, to think critically, to think laterally, and to think abstractly in order to solve puzzles.

Not all of these puzzles were great, however. Most gamers of this era will know what I mean by “Get glass” in Space Quest or only having three trips across the bridge in King’s Quest II.

Sierra’s games had a magic and a character that only LucasArts–makers of hits like The Curse of Monkey Island, Loom, and Maniac Mansion–came close to replicating, though some gamers say that LucasArts was the superior company. And there were, of course, pretenders: for example, the execrable Les Manley series took everything that made Leisure Suit Larry charmingly raunchy and did it wrong.

Sierra’s Oakhurst, CA headquarters

Sierra’s Oakhurst, CA headquartersFor a time, Sierra was on top of the world. Theirs is an “overnight success” story twenty years in the making . . . and then in the space of a year, it was all over. Ken Williams was ousted from the company he started, Roberta’s design for the latest installment of the groundbreaking franchise she created were being ignored, and soon they cashed out and left. Sierra would exist as a shell of its former self before succumbing to the limbo of corporate rights purgatory, and there would be no more games. No more innovations. No more quests.

So what on Earth happened to bring this gaming juggernaut to its knees?

That’s the question Williams seeks to answer in his self-published memoir Not All Fairy Tales Have Happy Endings. Now, this isn’t an autobiography of Williams’s life, though he does get into that to the degree necessary. This is an autobiography–and an autopsy–of Sierra On-Line.

Williams begins with his hardscrabble beginnings in rural Kentucky, his subsequent move to California, and the fact that school wasn’t for him. It bored him. Ken was a doer, and he liked to learn on the job. He did spend a year in college where he got bitten by the computer bug . . . and the love bug, where he met the more affluent Roberta Heuer, who would shortly thereafter become his wife. In these early days, you see how Williams was a go-getter who refused to take no for an answer. He dreamed of being rich and successful, and his life was bent towards that goal.

This early era of the Williams’s life is fascinating because it shows how the 1970s and 1980s were an America that doesn’t exist anymore. Computers were coming into their own, our cities hadn’t become dangerous urban war zones, and our institutions weren’t yet totally corrupt and incapable of performing their core functions. Ken was a very hard worker and an autodidact, the classic Baby Boomer who worked while putting himself through computer programming school, but that doesn’t take away the fact that the economic environment was like that of a better, foreign country to my thirty-nine-year-old self. The way Williams jumped from job to job, always getting paid more, is stunning. Back in those days, you could fart and land a sweet gig.

Anyway, it was at these various business, learning coding and programming and getting to play with the latest new technologies, that Roberta discovered text adventures, inspired Ken to push the limits of the hardware, began designing games, and setting Sierra on its path to glory.

This chunk of the book is really great because you get to see Ken’s business philosophy explained fully. His inspirations were Microsoft and Walt Disney, and he envisioned Sierra as a combination of the two: a forward-thinking, envelope-pushing technology company with a diversified portfolio that encompassed the total entertainment and productivity landscape, with a strong brand identification that was synonymous for “quality.”

And it was.

The list of Sierra firsts is pretty staggering, and I also appreciated Ken’s aggressive marketing strategy. The section on the risqué text adventure Softporn–the precursor to Leisure Suit Larry–and the subsequent controversial advertisement featuring three topless attractive young ladies in a hot tub (one of them was Roberta!) is a riot.

Williams never shied away from controversy

Williams never shied away from controversyNot All Fairy Tales Have Happy Endings doesn’t discuss the games themselves all that much, but that’s okay because it’s very entertaining to read about how Williams grew Sierra, fought various legal battles, expanded into sectors where competitors weren’t, and how running a free-wheeling young business is very different when shareholders and venture capitalists get involved.

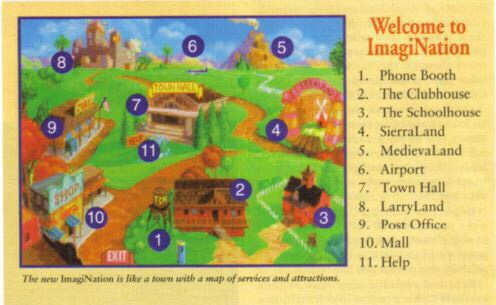

Speaking of venture capitalists and shareholders, this is where the downfall of Sierra begins. After running through business successes and failures, most notably The Sierra Network, Sierra’s proprietary online gaming/social networking community that was years ahead of its time. Interestingly, Williams had the idea to target seniors first to see if they were interested in playing card games with other seniors around the country, and the world. They were, and other party games as well as multiplayer role-playing games followed. However, an ill-fated partnership with AT&T and a loss of control killed The Sierra Network–later renamed The ImagiNation Network–and left a sour taste in Williams’s mouth, a sense of “What if I did this differently?”

Way ahead of its time

Way ahead of its timeThere’s a lot of this sentiment throughout Not All Fairy Tales Have Happy Endings. For every Sierra success, and there were many, it seems like Williams made a decision he regrets. A merger with Brøderbund almost happened, but management styles clashed a bit too much. Here are some more:

In the early 1980s Sierra declined to get into the console video gaming market. It seemed like a good idea at the time to avoid that sector, but time has proven otherwise.

Sierra had the Ultima license but gave it up after only publishing two games (Ultima II and the awful spin-off Escape from Mount Drash).

The founders of id Software, gaming legends John Romero, John Carmack, and Tom Hall, met with Ken and Roberta and expressed their interest in selling id to Sierra. Ken declined because, while the asking price of a few million wasn’t too much, he did not want to front id the $100,000 they were asking for. Williams claims there were legal issues with providing this cash up-front, but I’m skeptical. Williams was also sensitive to the violence of Wolfenstein, but thought the game was great. So id went their own way and became super-profitable superstars when Doom hit the scene. Still, Williams did get in on the first-person-shooter genre some years later by buying Valve and publishing Half-Life, which worked out for Sierra.

Williams turned down a young Jeff Bezos’s offer to partner on automating a way to scan book covers for this thing he was working on called Amazon. Oops.

This underscores another aspect of Sierra’s business strategy that I appreciated the insights into: Williams loved buying smaller studios and letting them retain their unique cultures. These subsidiaries would design the games and Sierra would provide the same level of promotion, production, and marketing they’d give to their in-house games. This worked great, and allowed Sierra to expand into genres such as flight simulation and sports.

Further, Williams was passionate about letting his designers have relatively free reign to make the products they were passionate about. The Two Guys from Andromeda, aka Scott Murphy and Mark Crowe, made Space Quest very differently than musician/comedian Al Lowe made Leisure Suit Larry. Both were different than former California police officer Jim Walls’s Police Quest series, or Christy Marx’s historically and mythologically accurate Conquests of Camelot and Conquests of the Longbow, Jame Jensen’s supernatural Gabriel Knight series, or husband and wife Lori and Corey Cole’s epic Quest for Glory games. The rule was, if you sold a lot, you got Williams’s attention and trust . . . and you got the budget you wanted.

Gabriel Knight: Sins of the Father

Gabriel Knight: Sins of the FatherSome games were flops. Strategy simulation Outpost was a much-hyped game that Williams greenlit on the promise of features to come that never materialized. The game was rushed for the all-important Christmas season but was nearly unplayable. Sierra’s credibility took a hit, and all of those glowing advance reviews left Sierra with serious egg on its face for perhaps the first time.

The book is full of inside stories like this. They’re instructive and fascinating. Generally, Sierra’s story is one of steady, sometimes explosive growth. The Williams’s got rich and Ken was able to live the lifestyle he fantasized about as a poor young Kentuckian. They treated their employees well, and soon the remote California mountain town of Oakhurst was a hub of activity with Sierra its main employer.

They eventually had to move to Seattle as the company grew. In order to get the top C-suite talent they wanted, they needed to be in a major metropolitan area. Things were looking up, until they weren’t. Isn’t that the way things always go?

What precipitated Sierra’s stunning, rapid collapse was the sale to Comp-u-Card (CUC), later Cendant, a giant company whose CEO Walter Forbes had been a good member of Sierra’s board since the early 1980s. Forbes was everything Williams aspired to be . . . except, perhaps, a hard worker. Williams recounts that meetings with Forbes and his inner circle involved discussing vacations and golf scores and little else.

Walter Forbes

Walter ForbesAnyway, Forbes approached Ken and Roberta about selling Sierra to him. His offer was so good that it would have been a dereliction of duty for Williams to not even bring it up to the rest of the board. Ultimately, despite Roberta’s bad feeling about both Forbes and the deal, Williams pulled the trigger in 1997.

Sierra was essentially over by 1998.

It turned out that Forbes and much of his crew had been cooking the books and overinflating stock prices due to some “creative” accounting. This was bad enough, but the fact that Sierra became a subsidiary of Cendant, and Williams had to share CEO duties with Bob Davidson of educational software giants Davidson. Needless to say, styles did not mesh, and while Williams was promised an equal voice, Davidson was promised full power. Which he had.

At the end of the day, Ken was ousted from his own company, Roberta finished King’s Quest VIII after a tear-filled development process that would be her last, and then the Federal government got wind of Forbes and company’s shenanigans and brought the whole house of cards down. So many Sierra employees lost everything they had, a fact that eats at Williams to this day. I do not find his pain over this contrived. Ken treated Sierra and its employees like extended family, and his agony over Sierra’s demise is palpable.

Vice.com, of all places, has a great piece about the corporate fraud that killed Sierra if you want to read something that goes into a little more detail than Williams does. https://www.vice.com/en/article/z3vem8/inside-story-sierra-online-death-cuc-cendant-fraud The Vice article is somewhat of a companion to the book, and I recommend reading it in conjunction with Not All Fairy Tales Have Happy Endings, or afterwards.

At the end of the day, though, Williams made out very well for himself. He and Roberta sail around the world and seem happy, though for my money the world is poorer for not having Sierra–wonderful, free-wheeling, unique, idiosyncratic, and innovative Sierra–and its games in it.

Williams has a very conversational, easy-going style that doesn’t get bogged down in too much technical or business jargon. Nor does he belabor the points he tries to make–for such a lengthy book, Not All Fairy Tales Have Happy Endings is an easy read. Interspersed into the main narrative are what Williams calls “Interludes” where he riffs on topics he didn’t think fit anywhere else. Some, like writing code, were beyond me but I read them anyway because they gave insight into Williams’s overall management philosophy and work ethic. Others, like his approach to marketing, game designers, and the pitfalls of working with family, were easier to understand. On the whole, it’s a little chaotic and stream-of-consciousness, but it works and really lets you peek into Williams’s head. Fascinating stuff.

Not All Fairy Tales Have Happy Endings is an excellent, candid, and uncensored look into one of computer gaming’ s most legendary companies. I highly recommend this for anyone who played a Sierra game, or anyone who is interested in this period of technological history. Hopefully Ken and Roberta get the chance to make more games in some way . . . and bring some of Sierra’s legendary game designers like Crowe and Murphy, the Coles, Lowe, Marx, and Jane Jensen with them.

Before games got all corporate and samey . . . before budgets got bloated and graphics became more important than gameplay and fun . . . before designers became political crusaders and all developers chased trends and created the same thing with a different name . . . there was Sierra. And they are sorely missed.

When you’re done with this book, read my book about Rush fandom.