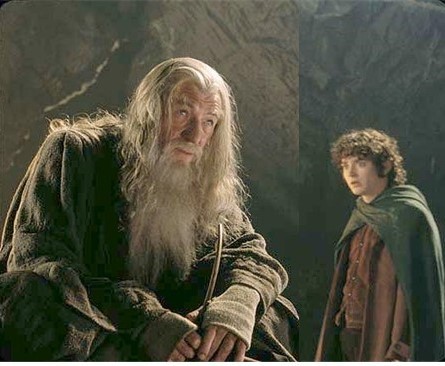

What To Do With the Time

“I wish it need not have happened in my time,” said Frodo.

“So do I,” said Gandalf, “and so do all who live to see such times. But that is not for them to decide. All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us.”

JRR Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring

If someone had told me in January 2020 that there would be a pandemic, I never would have thought that things would play out as they have. I would have expected the quarantine, masks, and upscaled sanitation, but I would never have imagined the controversy these measures could excite, nor the other social and natural upheaval that has played out alongside the pandemic.

I don’t think anyone can fully prepare for the future, even with a lot of facts to guide them. I figured I’d be ok during this pandemic because I’m a low-key prepper (just food and essentials storage—no bunker in the backyard—unless you count my hobbit-hole), we have computers with webcams, and my husband works at a job that would continue during a quarantine. I knew I was lucky.

But I didn’t foresee the depression that having kids lose their outlet of playtime with friends would produce, nor the anxiety over what the heck to expect from this virus that seems to hit very randomly—some just feel sick, others languish for weeks or months, and others die, and no one seems able to tell who will fall where. I also didn’t foresee the hatred that would seethe all over social media, nor the intensity of opinion that would split us as a nation, and how it all would affect my sense of well-being and humanity.

It seems so overwhelming, but we aren’t alone in this. Throughout history, people have grappled with the unknown, being forced to slog through unforeseen challenges to reach their goals. But if we’re going to learn anything from history (and I feel that’s the whole point of looking back at all) then I think it is this: they didn’t give up.

Take for example the lower classes of the Regency era. They made up more than 45% of the population, and yet they made less than 15% of the income (hmmm, looks like things haven’t really changed much worldwide). The normal avenues of improvement (education, promotion, investment) were denied them, generally from lack of funds (either personal or charitable), or lack of opportunity.

But while their lives were not easy, and we wouldn’t want to put ourselves in their shoes, people back then had something that we squint at today: a strong work ethic. If they were able to work, they would work, and they would work as hard and as long as it took to provide for their responsibilities. Though there will always be those willing to get something for nothing, there was a strong sense of pride in the laboring classes which kept the majority of them from accepting handouts or favors. They wanted to succeed on their own terms, and on their own power.

This is kind of a foreign concept today. With welfare, socialized medicine, and parents paying for their kids’ expenses well into their adulthood, it’s no wonder that we gape at the idea of someone refusing monetary help. We see the hardworking poor of the Regency as downtrodden—and many undoubtedly were—but there is a lot of evidence that they tended to take pride in the work of their own hands, and were happy.

The Penny Wedding by Sir David Wilkie

The Penny Wedding by Sir David WilkieWhich brings me full circle to what Gandalf said, which I can’t help linking with the quote from the Bible regarding lilies: sufficient is the day to the evil thereof. I think we can expect that our time will fill itself with plenty of evil, but we still have a choice of what to do about it.