Making A Scene

Hello everyone, Winnie Griggs here. As part of our Back To Basics series, I’m reprising a post I did here on Seekerville over 10 years ago as a guest - the importance and construction of story scenes

.

The workhorse of a story is not words, or sentences or even paragraphs – rather it’s the scene. It’s in a scene that we see the key element of any good story - namely relevant change.

It is the elements of both relevance and change that makes a scene a scene.

So with that in mind I’d like to discuss eight elements I believe make comprise the checklist for an effective scene:

For purposes of this discussion, let’s imagine we’re working on a scene where our heroine, Deanna Deeva, is recently divorced. She’s struggling with what impact the label of divorcée will have on her social standing. She’s been invited to a party hosted by a longtime acquaintance and the scene opens when Deanna arrives and parks her car.

1. In an effective scene - something happens

The ‘something’ doesn’t have to be remarkable - it can be as simple as a single activity or as complex as several dozen story beats rolled together.

For instance, in our scene with Deanna Deeva, if the scene revolves around her fear of going out in public again, the ‘beats’ to this scene might stop with her making the decision to leave her car and walk up to the front door. The party itself may be transitioned over entirely since in this case it was her decision to actually join the party that was important to the story and to showing some aspect of her character.

On the other hand, if the thrust of the scene is to show how she handles being out among her friends, the scene could be composed of a number of beats - arriving at the party, a few awkward conversations, perhaps an overheard catty comment, catching the eye of an intriguing-looking gentleman, and the unexpected arrival of the ‘other woman’.

2. An effective scene should have a focus or goal

In other words, our character(s) will strive to achieve something. Note, the author needs to look at this on two very different levels:

One, is to view it from the character’s perspective - what does the character hope to accomplish during the course of this scene?

The second is the reader perspective. What do you as the author want the reader to come away from this scene with?

In our scene with Deanna Deeva, the character’s goal might be to prove to herself that her social standing was not adversely affected by the divorce. The author’s goal for the reader, however, may be to deepen her understanding of some aspect of Deanna’s character, either a strength or a weakness.

3. An effective scene should elicit a reaction

A well-crafted scene will evoke emotion of some sort, both in the characters on the page and in the reader. Note, these won’t necessarily be the same emotions.

Again, in our previous scene with Deanna Deeva, depending on how the author plays it out, the reaction of our focal character could be one of mortification, determination, depression, irritation, or even victory.

On the other hand, the reaction of the reader might be one of sympathy, amusement or even annoyance. A good writer will choreograph her scene to tease the emotions she wants from both the characters and the readers.

4. An effective scene will have a story purpose

The whole crux of your scene’s reason for being is to move the story forward in some fashion. There are many different kinds of scenes - fight scenes, flashbacks, love scenes, opening scenes, turning points, climactic scenes - but no matter the type, a scene must have some effect on the focal character or overall storyline . Something necessary to the story as a whole must be contained within the scene to warrant its existence, otherwise it should be rewritten or ruthlessly cut. In order to pull its weight effectively your scene should Ideally perform at least two story functions - three or four would be better.

5. An effective scene should have structure

• As in a full-blown story, each scene must have a well-defined beginning, middle and end. It’s a mini-story of sorts - there is an inciting incident, a series of actions or beats, and then a resolution that tells us we’ve extracted everything we can from this particular scene. However, with the exception of the final scenes, the scene resolution does leave some unanswered questions, some loose ends that nudge the reader into the subsequent scenes to try to find the answers.

6. A scene should show logical, believable progression

The scenes should flow one from the other, sculpting and shaping your story in an aesthetically satisfying way that is entertaining and relevant.

Since scenes are the building blocks of your story, they must be carefully placed and arranged with every other scene in order to construct a pleasing, functional whole. Each scene builds on the one that came before and leads to the next - enhancing, changing, or redirecting your through line in some way, either subtly or forcefully - always pushing inexorably forward to the story’s resolution.

CAUTION: Logical doesn’t mean predictable, but given what the reader knows about the characters and the situation, it must be a believable next step.

7. A scene should have a mood or attitude

This is the underlying emotion in your story. Is it comedic, solemn, dark, light? Are there underlying urges or desires that drive your characters? These will play into your scene in subtle or overt ways, coloring the actions and goals, informing the responses of both the characters and the reader. Again, using our scene with Deanna Deeva at the party, even using the same action beats in the scene, they will play out very differently in a romantic comedy than they would in a romantic suspense or women’s fiction work

8. The final element an effective scene must have is the one I’ve mentioned before, the all-important element of change.

The change can be big or small, but you should be able to both identify it and see how it moves your storyline forward. This forward motion can come either through revelation or a relevant honing of character, world or plot. Deanna Deeva, or her situation, must be different at the end of the scene than she/it was at the beginning.

Again, if something doesn’t change, then no matter how lyrical and elegantly crafted, no matter how invested you as a writer are in it, the scene must be ruthlessly deleted.

One final thought - the clearest test of a scene’s effectiveness is to use what Raymond Obstfeld, in his book “Crafting Scenes”, calls the so-what factor. When you finish reading over your scene, ask yourself “so what?” Is this scene necessary? If you remove it will it actually affect the outcome of the story ? Does it fit with the scene before and the one after? Did something change? Was it significant enough for its own scene or could the key points be folded in one of the neighboring scenes?

If you answer those questions it will become obvious whether or not you've nailed the scene.

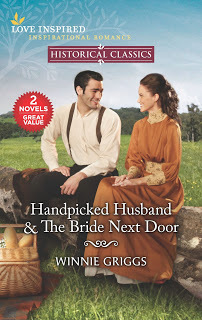

For a chance to win a copy of any book from my backlist, Including the new 2-in-1 re-release below, please leave a comment.

Handpicked Husband

Handpicked Husband

Regina Nash must marry one of the men her grandfather has chosen for her or lose custody of her nephew. But Reggie knows marriage is not for her, so she must persuade them—and Adam Barr, her grandfather’s envoy—that she’d make a thoroughly unsuitable wife. Adam is drawn to the free-spirited photographer, but his job was to make sure Regina chose from the men he escorted to Texas—not marry her himself!

The Bride Next Door

Daisy Johnson is ready to settle in Turnabout, Texas, open a restaurant and perhaps find a husband. Of course, she’d envisioned a man who actually likes her, not someone who offers a marriage of convenience to avoid scandal. Newspaper reporter Everett Fulton may find himself suddenly married, but his dreams of leaving haven’t changed. What Daisy wants—home, family, tenderness—he can’t provide…

BOOK LINK

.

The workhorse of a story is not words, or sentences or even paragraphs – rather it’s the scene. It’s in a scene that we see the key element of any good story - namely relevant change.

It is the elements of both relevance and change that makes a scene a scene.

So with that in mind I’d like to discuss eight elements I believe make comprise the checklist for an effective scene:

For purposes of this discussion, let’s imagine we’re working on a scene where our heroine, Deanna Deeva, is recently divorced. She’s struggling with what impact the label of divorcée will have on her social standing. She’s been invited to a party hosted by a longtime acquaintance and the scene opens when Deanna arrives and parks her car.

1. In an effective scene - something happens

The ‘something’ doesn’t have to be remarkable - it can be as simple as a single activity or as complex as several dozen story beats rolled together.

For instance, in our scene with Deanna Deeva, if the scene revolves around her fear of going out in public again, the ‘beats’ to this scene might stop with her making the decision to leave her car and walk up to the front door. The party itself may be transitioned over entirely since in this case it was her decision to actually join the party that was important to the story and to showing some aspect of her character.

On the other hand, if the thrust of the scene is to show how she handles being out among her friends, the scene could be composed of a number of beats - arriving at the party, a few awkward conversations, perhaps an overheard catty comment, catching the eye of an intriguing-looking gentleman, and the unexpected arrival of the ‘other woman’.

2. An effective scene should have a focus or goal

In other words, our character(s) will strive to achieve something. Note, the author needs to look at this on two very different levels:

One, is to view it from the character’s perspective - what does the character hope to accomplish during the course of this scene?

The second is the reader perspective. What do you as the author want the reader to come away from this scene with?

In our scene with Deanna Deeva, the character’s goal might be to prove to herself that her social standing was not adversely affected by the divorce. The author’s goal for the reader, however, may be to deepen her understanding of some aspect of Deanna’s character, either a strength or a weakness.

3. An effective scene should elicit a reaction

A well-crafted scene will evoke emotion of some sort, both in the characters on the page and in the reader. Note, these won’t necessarily be the same emotions.

Again, in our previous scene with Deanna Deeva, depending on how the author plays it out, the reaction of our focal character could be one of mortification, determination, depression, irritation, or even victory.

On the other hand, the reaction of the reader might be one of sympathy, amusement or even annoyance. A good writer will choreograph her scene to tease the emotions she wants from both the characters and the readers.

4. An effective scene will have a story purpose

The whole crux of your scene’s reason for being is to move the story forward in some fashion. There are many different kinds of scenes - fight scenes, flashbacks, love scenes, opening scenes, turning points, climactic scenes - but no matter the type, a scene must have some effect on the focal character or overall storyline . Something necessary to the story as a whole must be contained within the scene to warrant its existence, otherwise it should be rewritten or ruthlessly cut. In order to pull its weight effectively your scene should Ideally perform at least two story functions - three or four would be better.

5. An effective scene should have structure

• As in a full-blown story, each scene must have a well-defined beginning, middle and end. It’s a mini-story of sorts - there is an inciting incident, a series of actions or beats, and then a resolution that tells us we’ve extracted everything we can from this particular scene. However, with the exception of the final scenes, the scene resolution does leave some unanswered questions, some loose ends that nudge the reader into the subsequent scenes to try to find the answers.

6. A scene should show logical, believable progression

The scenes should flow one from the other, sculpting and shaping your story in an aesthetically satisfying way that is entertaining and relevant.

Since scenes are the building blocks of your story, they must be carefully placed and arranged with every other scene in order to construct a pleasing, functional whole. Each scene builds on the one that came before and leads to the next - enhancing, changing, or redirecting your through line in some way, either subtly or forcefully - always pushing inexorably forward to the story’s resolution.

CAUTION: Logical doesn’t mean predictable, but given what the reader knows about the characters and the situation, it must be a believable next step.

7. A scene should have a mood or attitude

This is the underlying emotion in your story. Is it comedic, solemn, dark, light? Are there underlying urges or desires that drive your characters? These will play into your scene in subtle or overt ways, coloring the actions and goals, informing the responses of both the characters and the reader. Again, using our scene with Deanna Deeva at the party, even using the same action beats in the scene, they will play out very differently in a romantic comedy than they would in a romantic suspense or women’s fiction work

8. The final element an effective scene must have is the one I’ve mentioned before, the all-important element of change.

The change can be big or small, but you should be able to both identify it and see how it moves your storyline forward. This forward motion can come either through revelation or a relevant honing of character, world or plot. Deanna Deeva, or her situation, must be different at the end of the scene than she/it was at the beginning.

Again, if something doesn’t change, then no matter how lyrical and elegantly crafted, no matter how invested you as a writer are in it, the scene must be ruthlessly deleted.

One final thought - the clearest test of a scene’s effectiveness is to use what Raymond Obstfeld, in his book “Crafting Scenes”, calls the so-what factor. When you finish reading over your scene, ask yourself “so what?” Is this scene necessary? If you remove it will it actually affect the outcome of the story ? Does it fit with the scene before and the one after? Did something change? Was it significant enough for its own scene or could the key points be folded in one of the neighboring scenes?

If you answer those questions it will become obvious whether or not you've nailed the scene.

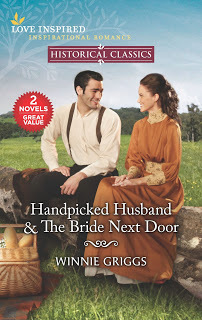

For a chance to win a copy of any book from my backlist, Including the new 2-in-1 re-release below, please leave a comment.

Handpicked Husband

Handpicked HusbandRegina Nash must marry one of the men her grandfather has chosen for her or lose custody of her nephew. But Reggie knows marriage is not for her, so she must persuade them—and Adam Barr, her grandfather’s envoy—that she’d make a thoroughly unsuitable wife. Adam is drawn to the free-spirited photographer, but his job was to make sure Regina chose from the men he escorted to Texas—not marry her himself!

The Bride Next Door

Daisy Johnson is ready to settle in Turnabout, Texas, open a restaurant and perhaps find a husband. Of course, she’d envisioned a man who actually likes her, not someone who offers a marriage of convenience to avoid scandal. Newspaper reporter Everett Fulton may find himself suddenly married, but his dreams of leaving haven’t changed. What Daisy wants—home, family, tenderness—he can’t provide…

BOOK LINK

Published on July 16, 2020 22:56

No comments have been added yet.