CAPTAIN VOSTERLOCH AND THE LONG PLAYING SPONGE

by William Sutton

and John Sutton

Do you sing to your sponge? Beware.

If a mysterious Parisian pamphlet of 1632 [see panel] can be credited,

your warblings may be played back the next time it is squeezed.

“A certain Captain Vosterloch has discovered a sponge

used by natives of the southern seas to communicate across long distances. Simply squeeze and the message spoken into it

is be replayed exactly.” [1]

Can a sponge really record sound? Where the legend lies on the scale between

bald fact and pure fiction requires debate:

the source material seems as obscure as the science.

But if Vosterloch did not exist, it seems a tremendous

lark to have invented him. For, as myth,

this fantastic portrayal of sound and porosity forces us to re-examine not only

the humble sponge, but also the history of sound recording, and our notion of

memory itself.

The phonographic poriferum, regarded as myth, takes its

place in a venerable tapestry of historical science fiction.

Ancient China, Greece and Egypt all produced magical

devices to duplicate sound or make statues speak, involving bellows, for

instance, or simply a hidden person. [2]

The 1589 speaking tube of Giovanni Battista Porta prefigures the thousand

mile speaker, a sealed wooden tube invented by Chian Shun-hsin in the

seventeenth century. [3]

Most grotesque is Rabelais’s idea [4]: the death throes of soldiers who died in

freezing icefields are gruesomely replayed when spring thaw the ice. Cyrano [5] convincingly describes talking

books with watch-like gears instead of pages.

A needle placed on the desired chapter produces a quasi-human voice –

speaking the lunar language, of course.

Whereupon we remember that Cyrano also claimed to have visited the moon.

Our South Sea setting raises familiar questions about the

colonial fascination with wonders. Why

do we project such fantasies on to the exotic other? To aggrandise our exploration,

certainly. To claim conquest of things

beyond our ken, perhaps.

What places our myth beyond the stock mythological topoi

is its pseudo-technological status. What

other myth of the exotic is so civilised?

So communicative? So modern?

Neither terrifying like dragons nor awe-inspiring like

the world’s edge, the recording sponge makes its (one and only?) appearance

just as Shakespeare’s Folio is starting to sell like hot cakes across the

channel. If printing techniques could

preserve and disseminate written words and pictures too (in the form of

engravings), why should speech – the most immediate form of communication –

prove recalcitrant?

We know that people were already fantasising about

recording sound. [6] What other

suggestions, besides our sponge, were being made? Let’s remember how easily technologies can be

invented and forgotten. Leonardo’s

helicopter is famed; but who remembers

Valdemar Poulsen? The Dane’s answering

machine, presented at the Paris Exhibition of 1900, was lauded by the press for

a quality of sound reproduction far outstripping the phonograph. [7]

Besides its value as myth and technological barometer,

our supersponge is also a historical metaphor for memory. As we strive to account for the vagaries of

remembering, our metaphors relate intriguingly to prevalent technologies. Nowadays, we tend to draw comparisons with

hard drives and their crashes, websites and their glitches. Not so long ago, we talked of filing things

away in the mind, like index cards and folders into boxes and cabinets.

But memory has been likened to such diverse containers as

the rooms of a house and the stomach of a cow. [8] If a sponge seemed a credible way to record

sound, what light does that cast on seventeenth century neurology and

psychology?

These primitive metazoa provide a familiar folk image for

forgetfulness [9], rather than retaining information. But Porifera – a group successful

since pre-Cambrian times via reproduction both sexual and asexual, viviparous

and oviparous – are valued and studied by biologists for clues as to how more

complex systems have evolved. [10] They

also provide, with their extraordinary cellular structure, fruitful comparison

with current models of the brain. Just

as our neural pathways form and reform in a fluid evolution, so their mobile

cellular systems carry out all vital functions, without developed tissue

organisation.

Perhaps we should hesitate, however, before writing off

the spongiform ansaphone as myth or metaphor.

Consider, behind fantastical sightings of sea monsters, the core

phenomena of whales and giant squid. And

how fanciful dragons sound … until you arrive on Komodo.

Can any spongologists help us uncover the grain of truth

in this pearl of a story? Or is it to historians of sound we should turn? Such a porous tape-recording requires sound

to be liquid: Vosterloch saw voices

soaked up, just as Rabelais described them freezing and thawing. What is the nature of porosity? Solid matter with holes like Swiss

cheese? Or must the stuff itself be

permeable?

Have we been too busy scrubbing ourselves down to

remember the more abstruse qualities of the spongiform? Think twice next time you catch yourself

singing in the bath. Perhaps one day

I’ll buy the White Album again, but on long-playing sponge.

__________________________________________________________ Fortean Times 2004

SIDE-PANELS,

ILLUSTRATION, AUTHOR INFORMATION

ENGRAVING

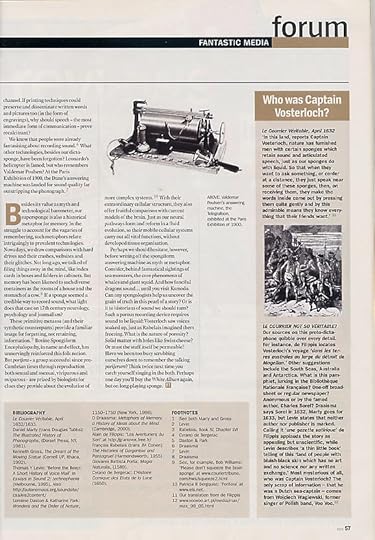

Draaisma’s book lifts a

wonderful engraving from Marty’s article.

This is footnoted as “A nineteenth century engraving from Le Courrier

Véritable of 1632,” so I can only assume there is no copyright.

SIDE PANEL 1 Le Courrier Véritable,

April 1632

“In this land, reports Captain Vosterloch, nature has

furnished men with certain sponges which retain sound and articulated speech,

just as our sponges do with liquid. So

that when they want to ask something, or confer at a distance, they just speak

near some of these sponges, then, on receiving them, they make the words which

were inside come out by pressing them quite softly and by this admirable means

they know everything that their friends want.”

[11]

“En ce pays, rapporte le capitaine Vosterloch, la nature

a fourni aux hommes de certains esponges qui retiennent le son et la voix

articulée comme les nostres font les les liqueurs. De sorte que quand ils veulent mander quelque chose, ou conférer de

loin, ils parlent seulement de près à quelqu’unes de ces esponges, puis les

ayant reçues, en les pressant tout doucement font sortir ce qu’il y avait

dedans de paroles et scavent par cet admirable moyen tout ce que leurs amis

désirent.”]

SIDE PANEL 2 Le Courrier Not So

Véritable?

Our sources on this proto-dictaphone quibble over every

detail. For instance, de Filippis

locates Vosterloch’s voyage “dans les terres australes au large du détroit de

Magellan,” but others suggest the South Seas, Australia, Antarctica, or South

America.

What is this pamphlet, lurking in the Bibliothèque

Nationale Francaise? One-off broadsheet

or regular newspaper? Is it anonymous or

by the famous Charles Sorel? Draaisma

says Sorel in 1632, Marty goes for 1633, but Levin states that neither author

nor publisher is marked. Calling it “une

gazette satirique” de Filippis applauds the story as appealing but unscientific,

while Levin describes “a thin little book” telling of this “land of people with

bluish-black skin which has no art and no science nor any written exchange.”

Most mysterious of all, who (if anyone) was Captain

Vosterloch? The only scrap of information

– that he was a Dutch sea-captain – comes from Wojciech Waglewski, former

singer of Polish band, Voo Voo. [12]

AUTHOR INFORMATION

Writer/musician, William Sutton, appeared in Ken

Campbell’s fortean epic, ‘The Warp,’ and has just moved to Brazil. wgq42@hotmail.com John Sutton, author of ‘Philosophy and Memory Traces,’

teaches at Macquarie University, Sydney, and presents ‘Ghost in the Machine’ on

East Side Radio. http://www.phil.mq.edu.au/staff/jsutton/

___________________________________________________________(150

words)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Le Courrier Véritable, April 1632/1633.

Daniel Marty (trans Douglas

Tubbs): The Illustrated History of Phonographs, (Dorset Press, NY, 1981).

D. Draaisma: Metaphors of Memory, a history of ideas about

the mind (Cambridge, 2000).

Thomas Y. Levin: ‘Before the

Beep: A Short History of Voice Mail’ at http://autonomous.org

Alain de Filippis: ‘Les Aventuriers du Son: sur l’emploi du son

et du bruit au fil des siècles et des civilisations …’ at

http://granuvox.free.fr./

Francois Rabelais (trans J.M.

Cohen): The Histories of Gargantua and Pantagruel (Harmondsworth, Penguin,

1955)

Giovanni Battista Porta: Magia Naturalis, 1589.

Cyrano de Bergerac: L’Histoire Comique des Etats de la

Lune (1650).

FOOTNOTES

1 Le Courrier Véritable

2 Marty

3 Levin

4 Rabelais, Book IV, Chapter LVI

5 Cyrano de Bergerac

6 Draaisma

7 Levin

8 Draaisma

9 See for example Bob Williams:

‘Please don’t squeeze the brain sponge’ at

http://www.courier-tribune.com/nws/sq...

10 Patricia R Bergquist: ‘Porifera’ at www.els.net.

11 Our translation from de

Filippis’ excerpt

12

http://www.voovoo.art.pl/media/max/ma...

OTHER POSSIBLE

TITLES

Is there a spongologist in the house?High

Fidelity SpongeSpongiform

Audio TapeDictaspongeListen very carefully, I will squeeze this only once

Please Feel Free to Share: