An open question about speculative fiction.

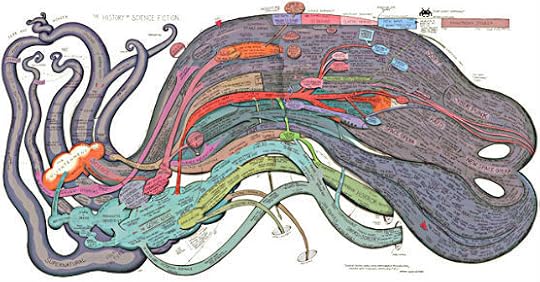

Click for a link to a high-res version of Ward Shelley's brilliant "The History of Science Fiction." I love this image so much that I hung it over my desk.

In an earlier post, I ventured a functional definition of speculative fiction. I said that a manuscript is "speculative" (i.e., fantasy, sci-fi, or anything in between) if it requires the writer to invent a rule or condition for their world that acts as a metaphor for the novel's theme. In other words: If you make something up, that something has to offer the reader a clue to what the book is about. Otherwise it's gratuitous.

Yet as I plan my next novel, I am reminded of Occam's Razor, which says that the simplest explanation for anything is usually the truest one. The problem with my earlier definition is that it doesn't always work; there are lots of books about dragons, fairies, and/or outer space that use speculative elements just for the fun of it. Some readers like to read about dragons, for instance, so a market exists for writers who enjoy telling dragon stories. Simple as that. There is no rule that says all dragon stories must be important social commentary.

So let me try a simpler definition. Where all fiction involves five basic elements–premise, theme, voice, character, plot, and style–speculative fiction also involves a sort of sidecar to premise: the concept.

So, if premise is what the story is about in a few simple sentences, the concept is the invented-but-believable element that separates the story world from reality. The concept could be anything: vampires and why they exist (Interview with a Vampire), a medieval world inhabited by dragons (The Dragonbone Chair), a future America in which fertile women are required to reproduce (The Handmaid's Tale), or a alter-reality in which Irish immigrant spirits are at war with Native American spirits (Forests of the Heart). If your novel uses a concept, then it has a speculative element. Simple as that.

So, here's my question. What is the difference between realist fiction and speculative fiction?

And a bonus question: Where is the line that separates books shelved in a store's "general fiction" section and its "sci-fi and fantasy" section?

newest »

newest »

I don't think that there are always clear lines between speculative and realist fiction, and it seems to me that Shelley's map helps us see a fluid and organic relationships between different literary genres. It often seems to me that my favorite works cannot be pigeon-holed: they borrow from so many different wells.

I like Philip K. Dick's definition of science fiction, however, because it is broad enough to include speculative works outside the spaceman mold:

"We have a fictitious world; that is the first step: It is a society that does not in fact exist, but is predicated on our known society -- that is, our known society acts as a jumping-off point for it; the society advances out of our own in some way, perhaps orthogonally as with the alternate-world story or novel. It is our world dislocated by some kind of mental effort on the part of the author, our world transformed into that which it is not or not yet. This world must differ from the given in at least one way, and this one way must be sufficient to give rise to events that could not occur in our society -- or in any known society present or past. There must be a coherent idea involved in this dislocation; that is, the dislocation must be a conceptual one, not merely a trivial or a bizarre one [ . . . .] so that as a result a new society is generated in the author's mind, transferred to paper, and from paper it occurs as a convulsive shock in the reader's mind, the shock of dysrecognition."