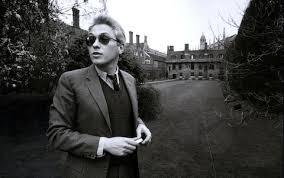

Once In A Lifetime: Eric Griffiths (1953 –2018)

I was one of Eric Griffiths’ first students at Trinity, back in 1980. I remember the excitement at the prospect of a very young new English fellow arriving. He was known to be brilliant and a protégé of Christopher Ricks, with a slightly dark reputation for having a wild side.

I was one of Eric Griffiths’ first students at Trinity, back in 1980. I remember the excitement at the prospect of a very young new English fellow arriving. He was known to be brilliant and a protégé of Christopher Ricks, with a slightly dark reputation for having a wild side.

He certainly enjoyed being a Cambridge maverick. But he did also prove an extraordinary brilliant teacher and this of course is his true legacy.

A sometimes partial one – he could be unfair to those he excluded from his circle and I will always remember the shocked tones with which he once told me a student was doing a thesis on Tolkien – but if he engaged with you, it was a life transforming experience.

For Eric, the study of English literature mattered: in a heuristic way, in a way that constantly questioned one’s own responses and assumptions, in a way that affirmed what it is to be alive and to process mute swirls of consciousness into words on the page.

He had a passionate engagement compared to the bland ministrations of much of the English literature industry and was impatient with the narrowness of their specialist vision – just as, after his conversion to Catholicism, he came to dislike the criticism of metropolitan literary papers with what he saw as their dull modernist orthodoxy and lack of true moral compass. Eric was an academic, but was never an academician. He never played the game of career advancement. He was a true scholar in the sense that all he wanted in life was a room in which to keep his books.

He had a passionate engagement compared to the bland ministrations of much of the English literature industry and was impatient with the narrowness of their specialist vision – just as, after his conversion to Catholicism, he came to dislike the criticism of metropolitan literary papers with what he saw as their dull modernist orthodoxy and lack of true moral compass. Eric was an academic, but was never an academician. He never played the game of career advancement. He was a true scholar in the sense that all he wanted in life was a room in which to keep his books.

The figure that inevitably comes to mind is that of Coleridge, standing in his study at Greta Hall with its big windows, looking out at a vista of mountains and space in which all seemed possible, but nothing ….was quite within reach. The central image in Eric’s biographia literaria would be of him pacing his study over Neville’s Court, listening to Talking Heads, chain-smoking and chain-drinking gin and tonics, engaging with his writers like a shaman summoning up spirit gods from the past with the aid of hallucinogenics (although harder drugs were one of the few vices Eric did not aspire to) but never quite able to wrestle them to the floor.

For Eric was suspicious of theory and suspicious of any critical conclusion that tied up a writer in a neat cardboard box and delivered it in gift wrapping to the reader. To use a theoretical term that he might not have approved of – now that he is no longer here to give a despairing glance at any solecism – he was suspicious of closure.

And this is not closure for Eric, despite the cruel, cruel way he was taken from us.

He lives on in the minds and hearts of those he taught. He was a mesmeric and powerful influence on many. He was a truly Socratic presence. And often a very funny and loyal one.

As we grow older, we collect the voices of those who’ve passed inside our own heads. I will hear him in my mind until the day I die, cajoling, exhorting and above all questioning, which surely is the true role of a critic in a world so complacent in its own certainties.

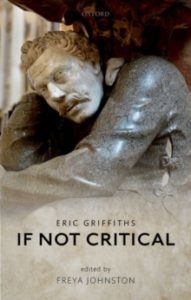

By great good fortune, Oxford University Press have recently published a volume of his lectures, If Not Critical, retrieved from his computer after his stroke, for which the editor Freya Johnston is to be much commended. My copy arrived on the night that he died after his long illness. They capture perfectly what she describes as the ‘fast, sardonic, protesting and exact’ tone of his public voice. There are apparently many more of these essays. I suspect they will be his true legacy.

By great good fortune, Oxford University Press have recently published a volume of his lectures, If Not Critical, retrieved from his computer after his stroke, for which the editor Freya Johnston is to be much commended. My copy arrived on the night that he died after his long illness. They capture perfectly what she describes as the ‘fast, sardonic, protesting and exact’ tone of his public voice. There are apparently many more of these essays. I suspect they will be his true legacy.

Posted on the day of Eric’s funeral in Cambridge, November 9, 2018