“The Waking” in Slaughterhouse-Five

For many of us, Kurt Vonnegut’s “Slaughterhouse-Five” is a brilliant example of post-modern writing meeting science fiction. His anti-war novel’s non-linear structure and lack of heroes shows the desperate attempts of Billy Pilgrim to come to terms with catastrophic events that are beyond his control. But Vonnegut is also notorious for jumping into his texts, both as a character and as himself. So even if we’re not too sure what the point is of post-modern writing, we cannot help but figure out it must have something to do with an ongoing dialogue between us readers, the author, and the characters in the story.

What is “The Waking” doing in S-5?

Much has been written about S-5 and I don’t want to add to the noise around free will versus determinism or whether the Tralfamadorians were “real”. What I do want to focus on is the little stanza from Theodore Roethke’s poem “The Waking” that appears in the first chapter of the story.

Recall what the first stanza of the poem is:

I wake to sleep, and take my waking slow.

I feel my fate in what I cannot fear.

I learn by going where I have to go.

It is an odd thing, isn’t it? And what possible purpose could it serve in Vonnegut’s novel?

Well, as astute readers, we recognize that while it may be easy to skim over this part of the first chapter, the poem was not thrown in just for fun. There is always something interesting and compelling in these types of novelistic insertions, so let’s have a closer look at the meaning of “The Waking” in the context of Slaughterhouse-Five.

First, let us recall that the first and last chapters act as bookends to this non-linear adventure of Billy Pilgrim during the fire-bombing of Dresden and his life afterwards as an optometrist. In fact, other than the first and last chapters, you could begin the story anywhere and still get it. That’s the fun on non-linearity in literature.

But it’s in the first chapter where Vonnegut outlines his reasons for writing the “lousy” book at all. He wanted to write an anti-war novel that dealt with the reality of Dresden and his own survival in a slaughterhouse. He wanted to show the absurdity of war, human fragility and whether we can live as deterministic beings. Of course, the story is much more than just that.

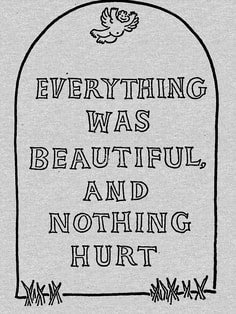

Just as Billy Pilgrim awakens to his own social reality – whether on Earth or on the planet Trafalmadore – Vonnegut too awakens to his own need to deal with his Dresden demons. In this way, Roethke’s poem begins to make more sense and in fact sets the tone for the rest of the story.

I wake to sleep, and take my waking slow.

Let’s look at the first line of the poem: I wake to sleep and take my waking slow. What does it mean to “wake to sleep”? This apparent paradox simply means that we are awakening to a dream-like world where things don’t make sense. Look, you know this is true from your own dreams. When you’re dreaming, you think what’s happening in your dream is real, even though it makes no sense. This is what the poet is getting at here. The context is that both Vonnegut and the reader needs to awaken to the fact that the world is absurd, and trying to make sense of it all can simply lead to frustration and confusion.

Now, the “take my waking slow” business means just what it says. This is not some kind of Joyceian epiphany. It is a growing awareness, an increased understanding over time.

I feel my fate in what I cannot fear.

This second line of the stanza appears to be just as confusing as the first line. What does it mean to “feel fate”? How does one do that exactly? Well according to Roethke, he feels fate in what he cannot fear. This is a bit tricky, so consider this: what are the things that you cannot fear? I’m not asking about things you don’t fear; I’m asking about what you cannot fear. In other words, those things where fear is impossible.

It might take a bit of thinking to figure that one out. If I cannot fear something, it means that no matter what happens, I will be safe and secure and unharmed. Does that make me a fatalist, happily going about my business because nothing I do is really because of my own free will? If the universe is deterministic, then is it even possible for me to fear anything? Ahh, padawan, now we’re getting somewhere. It’s almost as if the poet is saying to let it all go.

I learn by going where I have to go.

Well now we come to the concrete connection with Vonnegut’s writing journey. Just as he must go back to Dresden and write his anti-war novel in order to heal, so do we. By going back to our dark spaces and our hurts and shames, we too learn. We too awaken to a better understanding of the world and our lonely place in it.

In other words, ignoring our psychological pain does not help us get better in any way. We need to revisit our painful places, both in our minds and physically as well. This is the significance of having Roethke’s poem in Vonnegut’s novel. The book is an awakening for the author. It is also an awakening for us.

Published on June 06, 2018 03:44

No comments have been added yet.