On Wandering Monsters, Part 4: Wandering Traps?

I’ve always hated traps.

There, I said it. Aside from the occasional

booby traps placed by the kobolds and the Ettercap in Into the Living Library, in my

entire GMing career, I’ve only ever used a single trap—also in Into the Living Library—and it was

really more of a plot device than anything else. It was a clearly marked death

trap to encourage the party to turn around and do some exploring and

roleplaying to find a bypass. The trap was a lock; Leonard’s Lightning

Redirector was the key.

Traps are boring. The Rogue makes a Perception Check (and fails it, because

Rogues routinely have terrible Wisdom), then passes their ensuing Reflex save,

and we all move along. Alternatively, the save is failed, and the Rogue takes

damage, which no action or decision from the Player could have avoided in any

case. Some amount of damage will just be taken and the dice will decide how

much; it’s not particularly engaging or interactive. The party recognizes this is

the cost of doing business and deducts a bit more of their profit into healing

potions.

Traps are literally business expenses. Taxes.

But I used to think the same thing about

Wandering Monsters, and lately I’ve come to love those. So far, most of what

I’ve written in this series have been things that have been percolating in my

mind for some time now and tested in Into the Living Library and City of Eternal Rain, but this is largely

new territory.

Can our Wandering Monster table include

traps?

In Living

Library, some minor traps were on

the table as “hints,” but I’m envisioning something much more

comprehensive. If traps are sufficiently foreshadowed—as Wandering Monsters can

be—they will feel less random, and therefore less like wastes of time. If they

aren’t settled solely by a series of dice rolls, but rather decisions (that may

include and affect dice rolls), they will feel less punitive.

“Wandering Traps” don’t

necessarily replace bespoke, custom-placed traps, just as Wandering Monsters

don’t replace designed set-piece encounters. They can work side-by-side,

simulating an active dungeon ecology while reducing GM prep work as a dungeon will

only need a handful of unique, hand-placed traps as the procedurally-placed Wandering

Traps can pick up the slacks.

This post will be an experiment in adding

traps as “creatures” to the Wandering Monster table described in the

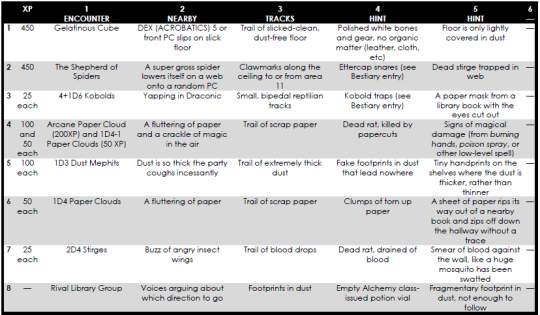

last post, which looked like this:

(The previous, simplistic attempt at

including traps into this table can be seen in the Hint column for the Shepherd

of Spiders (an Ettercap) and for kobolds). Let’s see if we can do better.

In the movies, landmines never just explode. Rather, a character steps on

one, then realizes what they’ve done. A tense scene develops wherein the victim

and his comrades attempt to defuse the mine, or trick it somehow, into letting

the victim step off of it without detonating. Do they dare split up and go for

help, leaving the victim all alone?

In many ways, landmines were designed with

this aim in mind, as rather than simply killing one person, a single mine can

potentially delay an entire group for hours, which in many contexts is more

valuable.

What if in D&D, encountering a trap

doesn’t immediately mean that it goes off, but rather, the party (in

particular, whoever is in front) finds themselves on the verge of detonating the trap, and then has to figure out how to get

out of their predicament?

For traps, instead of an ENCOUNTER column, I’ll put in a NOBODY MOVE column. This entry

represents some poor soul suddenly realizing they’re in harm’s way, that is,

standing on the pressure plate (“don’t even breathe or you might set it off!”), with their foot on the

tripwire, or standing on a slowly-creaking false floor above spikes. If they

stay perfectly still, the party might

be able to devise a solution. As this replaces ENCOUNTER, it must be the most immediately dangerous roll, so other

columns ought to be foreshadowing or less-immediate threats.

Unless the party is actively searching for

traps, spotting them should be incredibly difficult. We can safely make this a

hard check, because, as mentioned earlier, failing no longer results in automatically

setting off the trap. A WISDOM (PERCEPTION) check of 20, or an INTELLIGENCE

(INVESTIGATION) of 15 if they are actively searching, is probably a good DC.

Success should be uncommon but not impossible.

However, spotting traps is almost as fun as

getting caught up in them, as it also leads to interesting choices—does the

party press ahead and risk setting off the trap, attempt to disarm it, or take

another route and hope that they can bypass it?

Now, we can lower the DC, but that runs the

risk of meaning higher-level and higher-wisdom characters will always spot traps, which is boring. So

how about we just add another column to the table wherein the party spots a

poorly-hidden trap? TRAP AHEAD can

be our second column, representing exactly what it sounds like—the party

notices a poorly-hidden trap blocking their path, and must choose to brave it

or turn back.

We’ve figured out how traps are spotted,

but unless the party actually knows what triggering the pressure plate will do, they won’t know how afraid to be.

We need to tell the party that the trap shoots poison darts without actually

shooting them with poison darts—this is where our HINT columns come in. We’re still short a column, so let’s extend

this principle further with a FALSE

ALARM column—the party encounters a trap, but it’s either a dud or

malfunctioning. The existence of duds has the added advantage of making them

never know if the trap in front of them is ‘live’ or not.

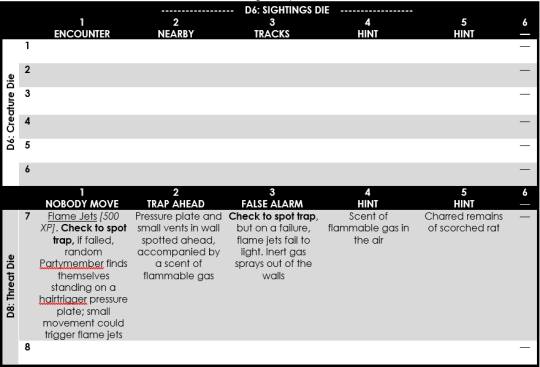

Here’s an example of how this might come

together. For a finished product, the six creature slots and both trap slots

would be filled in, similar to the table from Into the Living Library.

Alongside the entries in the table, as with

Wandering Monsters, a paragraph or so of description kept nearby is needed to

include a little more detail, and rules like DCs and damage.

Flame Jets. This trap is triggered by a pressure

plate—a disguised flagstone in the floor that depresses with weight placed on

it, causing the arrows to fire. The mechanisms are old, faulty, and weren’t

originally made by a society with particularly advanced engineering, so the

same plate can be walked over many times before it finally decides to trigger, blasting

scorching jets of flame through hidden vents in the walls. If the trap is

triggered, anyone on the pressure plate, anyone attempting to disable the trap,

and anyone else within 10 feet must make a REFLEX SAVE of 12 or better or take

2D10 fire damage. Because the pressure plate is faulty, it may not necessarily

be the partymember in front who realizes their danger—choose your victim at

random from among the party.

We can just append the traps to the end of

the Wandering Monster table. If the GM rolls a D6 (the Creature Die), only

creatures can be encountered; on a D8 (the Threat Die), higher rolls result in

traps. Perhaps D8s are rolled when the party enters new areas (that might

contain traps) while D6s are rolled when the party backtracks, or enters an

empty room. Areas that the party will spend more time in should have more

monsters and traps and use larger dice, though the balance of how many monsters

vs. how many traps will depend on the nature of the dungeon. For example, a

dungeon with a D6 creature die and a D12 threat die will have 6 creatures and 6

traps (with 31 possible unique rolls) will feel very different from a D10

creature die and a D12 threat die, which has 10 creatures but only 2 traps. A

larger number of monsters and traps will mean more variety, but also a greater

likelihood of encountering unforeshadowed traps and monsters. Consider instead dividing

the dungeon into smaller chunks, each with corresponding (smaller) tables, such

as a D4 creature die and a D6 or D8 threat die.

If the party is in a place where they’re

disarming a trap, it either means that they’re very nervous (because someone is standing on the trigger), or were

fortunate enough to spot it before anyone got in the way. The 5th

edition DMG provides scant rules on disarming traps, so I’ll write some of my

own to fit this new system. The DC to disarm the trap should be fairly low, as

the consequences of failure are quite high and it’s probably going to be the

same PC (i.e., the Rogue) who disarms every trap, and as such suffers the most

for failure. An actual plan for disarming the trap has to be presented—simply rolling

a die isn’t enough, as it puts us right back into “roll dice and take

damage, then move along” territory. Feel free to adjust the DC for dungeons

aimed at higher-level play. Similarly, the rarer the traps, the higher the DC

should be, as you run less risk of piling damage unfairly on the Rogue (who can

take one or two trap hits, but not dozens). Correspondingly, for dungeons with

many traps, I would keep the DC quite low. Here’s a first pass of the specific

rule I would use for this:

If an armed

trap is discovered (either from a “NOBODY

MOVE” or a “TRAP AHEAD”

roll), the party will often try to disable it.To disable

the trap, someone first must devise a plan—simply saying “I try to disable

the trap” and rolling a die won’t do. Instead, the Player might declare

that their character will try to wedge a knife under a pressure plate to

prevent it from triggering, or pack a scythe blade’s wall slit full of rocks to

block it from swinging, or plug a dart trap with wax to gum up the mechanism, or

the like. Creativity in this step should be encouraged.After

devising a plan, a skill check must be made. Normally, this is a Dexterity

check using Thieves’ Tools, but depending on the plan, other abilities, tools,

or skills might come into play. Regardless of the skill used, a roll of 12 or

better is a success. A particularly good plan provides advantage, while an

uninspired or foolish one incurs disadvantage. If the Party has encountered an

identical trap previously and has closely examined its workings, the Player

also gets advantage on this roll.A successful

check disables the trap, allowing the Party to bypass it safely. Depending on

the plan presented, the trap might be permanently destroyed or simply

temporarily bypassed. A failed check sets off the trap, which can harm whoever

tried to disarm it, anyone standing on the trigger, and potentially others as

well. If the trap remains a hazard after the party has left, the GM should be

sure to note on her map where the trap is and what state it’s in, in case the

party returns.

Sir Poley's Blog

- Sir Poley's profile

- 21 followers