On the Wandering Monster, Part 2: Narrative and Foreshadowing

In part 1 of this series, I admitted to having

feared and misunderstood Wandering Monsters in D&D for years, and resolved

to find a way to make the system work.

Now, I’ll examine a few ways of looking at Wandering

Monsters that aren’t a waste of time.

One of the major criticisms with Random Encounters

(which are closely related to, but not quite the same as, Wandering Monsters)

is that they feel, well, random. You’re

walking along, minding your own business, and suddenly a lone owlbear attacks.

You’d never heard that owlbears lived in this forest, and you’ve seen no sign

to hint at their presence thus far. Once you kill it (of course you will),

nobody will ever mention them again. They are battles devoid of narrative or

stakes, and thus, they are a waste of time.

Does it have

to be this way?

These terms are used

almost interchangeably, and are very similar. In lots of ways, if we can fix

one, we can fix the other, so I’ll be mentioning both. Wandering Monsters

specifically refer to encounters found in

a dungeon, while Random Encounters seem to be encounters found in the wilderness. Wandering Monsters,

as the name suggests, usually result in a battle, while Random Encounters

(which are more neutrally-named) can just as easily be a run-in with a

travelling peddler or caravan.

Over at The

Alexandrian, Justin Alexander notes that he suspects, waaaaay back in OD&D,

that Random Encounters were intended not as a single battle, but as an entire

adventure hook. He points out that a Random Encounter could potentially

generate hundreds of bandits, complete with their own officer hierarchy and

magic items, which was obviously out of the scope of a single battle.

Potentially the army

of bandits could be a backdrop to a role-playing or stealth challenge, wherein

the party sneaks by or negotiates their way through the bandits. Similarly, the

GM could map out an entire bandit base as a dungeon, wherein the party fights

or sneaks their way in, kills the leader, takes her magic gear, and gets out.

That’s all great in theory, but to me, in practice, this

sounds like a hell of a lot of work. Is the GM seriously expected to create an

entire adventure because she rolled a 1 on a D6 for a Random Encounter roll?

What about all the Random Encounter rolls made as the party heads back to base

to sell their “liberated” bandit loot? The goal here is to reduce the GM’s cognitive load during

play, not massively escalate it.

This method of looking

at wandering monsters—that each roll potentially generates an entire new

subplot—is especially problematic if the party is already working their way

through some kind of narrative.

Except in the most

extreme sandbox-mode playstyles, most GMs don’t want a die roll to

spontaneously generate entire narratives, so D&D as a whole seems to have

mostly abandoned this idea entirely, stripping the narrative out of Random Encounters

to reduce distractions, resulting in wilderness and dungeon run-ins completely

devoid of story. However, let’s not throw the baby out with the bathwater—what

if we use the Wandering Monster roll to deliberately

hook the players into existing narratives, rather than create new ones?

Lantzberg, the setting

of City of Eternal Rain, uses this approach, though it’s possible to go further with it. In City of Eternal Rain, Random Encounter

tables can result in run-ins, or clues to the identities of, a monster and a

murderer. Additionally, some of Random ‘Encounters’ are job postings that launch

pre-written minor sub-adventures. Instead of thinking of Random Encounters as a

distraction from the adventure, why

not tailor them directly into the

adventure? Populate your Wandering Monster tables with clues, hooks, and named NPCs

or monsters and try to get the best of both worlds.

Unlike the OD&D

style of having Wandering Monsters dominate the current adventure, we want a

solution in which the wandering monster table assists the GM, rather than taking

over entirely. Think more like Google Maps—which barks directions at the

driver as she needs them—and less like a self-driving car, which obsoletes the driver

entirely.

We want a solution in

which the GM can seamlessly integrate the procedurally-generated content of a Wandering

Monster table with their own hand-made narrative content. The Wandering Monster

table handles the gruntwork of believably populating a forest or dungeon,

letting the GM focus on bigger, better things. This only works if the Wandering

Monster table is effortless (which is to say, it doesn’t require dozens of subsequent rolls to describe an entire

bandit army) and the results are difficult to separate from the GM’s

hand-crafted content. This is hard to do as long as Wandering Monsters remain completely

devoid of narrative or foreshadowing, which brings up the question: how do we foreshadow

a random roll without causing more

work for the GM?

I mentioned above the

problem of the 'Random’ Encounter, that is, that it is meaningless violence

entirely devoid of context, drama, or warning. This can

seem an inevitable result of using random tables as content generation during

play, but what if I told you it didn’t have

to be like that?

The best solution I’ve

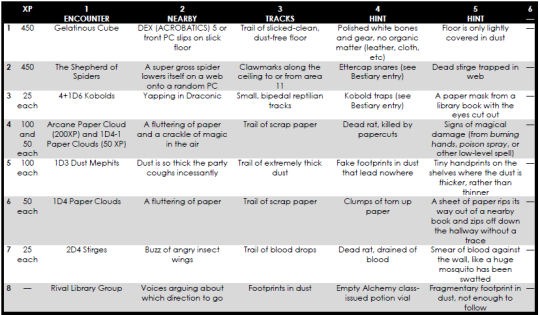

found online can be found over at the Retired Adventurer. I shamelessly cribbed this system, with a few

modifications, for use in Into the Living Library.

In classic D&D,

when a Wandering Monster roll is called for, the GM rolls a D6. On a 1 (or 6, there’s

some controversy there), they roll again on a table of monsters. This system

replaces that entirely, but maintains a 1 in 6 chance of actually bumping into

a monster.

With this system, the

GM rolls one die for the row, and another for the column. The row determines

what kind of monster is discovered, and the column determines what information

or threat that monster reveals. For instance, a row of 7 (“Stirges”)

and a column of 3 (“Tracks”) provides a trail the party can follow,

if they choose, to find some Stirges. Column 2 (“Nearby”) means that the

next time you roll on this table, skip the monster roll and use the previous

result. This means that the party is much more likely to encounter the monster

that just spooked them, simulating it being just around the corner. The odds

are low (only 1 in 6) that the party will encounter a given monster before

seeing some kind of hint as to their existence, meaning that they don’t often feel

“random.” For potentially several sessions, the party have been

seeing bits of torn paper here and there, so someone is bound to say

“ah-HAH!” when they finally encounter the animated clouds of paper

that are responsible, creating a simple narrative for each battle.

Each monster has an

accompanying key with a paragraph or so more information describing their

nature and tactics. For example:

The Shepherd of

Spiders. A single shepherd of spiders—an ancient ettercap—makes this

level of the library its home. An ettercap is a very powerful creature to

attack a first-level party, which is fortunate, because this one won’t. The

ettercap in the library is very stealthy and has no interest in a stand-up

fight. If it is encountered, it can only be spotted on a WISDOM (PERCEPTION)

roll of 18 as it hides among the shadows in the ceiling. It will try to use its

webs to disarm the players, picking off their weapons one at a time. If the

party fails their perception check, the ettercap will steal a weapon, wand,

staff, scroll, etc. from a random character, starting with their biggest weapon

and working its way down. On a DEXTERITY SAVE of 14, a character can snatch the

weapon as it leaves its sheath/strap/etc., and discover the ettercap in the

process. Otherwise, they only notice 1d6 minutes later that their weapon is

missing. Once a weapon has been stolen, or if it has been discovered, the

shepherd of spiders will flee back to its lair in area 11. The shepherd has

been doing this trick for a long time, and is very fast. The shepherd’s goal is

to render the party sufficiently helpless that they will be killed by the other

denizens of the library, and then feast on their corpses. There is only one

shepherd of spiders; if it has been slain, then ignore further wandering

monster rolls of 2. The shepherd is devious; it will create snares with its

webs for the party while they aren’t looking.

That table and this

paragraph is all that is needed for an Ettercap to wage a one-spider Die Hard-style guerilla campaign against

the party, all without requiring one iota of brainpower from the GM. The table tells the GM when the Ettercap lays a trap, and the

paragraph tells it how it attacks (it doesn’t). Note also that the Ettercap is

a full 2 CR higher than the party’s level, meaning that it could dismember the

lot of them without breaking a sweat. This would normally rule it out of a 1st-level

adventure (greatly reducing the array of monsters available to the GM, and letting

the players get complacent as they move from one level-appropriate encounter to

the next). Elsewhere in the adventure, rules on the spider’s snare traps are

provided. If the party manages to corner and kill the Ettercap, they will feel enormously self-satisfied, as they finally

bagged the bug that had been laying traps for them.

Sir Poley's Blog

- Sir Poley's profile

- 21 followers