On Towns in RPGs, Part 4: The Cobblestone Jungle

In the first article in this series, I embarked on an ill-defined

quest to figure out what, if anything, a town map is actually for in tabletop play.

In the second,

I took a look at the common metaphor comparing towns to dungeons—unfavourably.

In part 3, I proposed an alternate

metaphor—that cities are more like forests than dungeons.

Now, we’re going to draw parallels between

forests and cities to see what implications there are to a GM.

Every GM with even a gram of experience has

sent their party through a forest at some point. Forests are almost as familiar

an environment to GM as dungeons, while running urban adventures is a continual

source of confusion and worry. So let’s see what we can learn about running an

adventure by pulling ideas from forests.

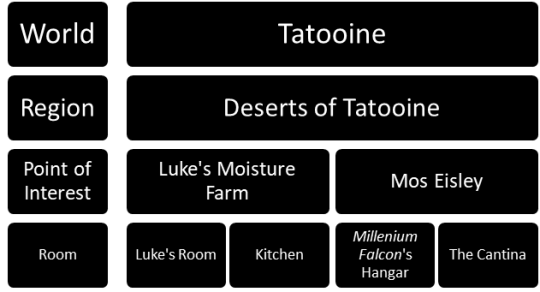

The way I often conceive of D&D worlds

is in layers. Each layer contains one or more smaller areas, on which you can (metaphorically)

click, zoom in, and see more subdivisions. This mindset might be a result of video

games like Final Fantasy where the

overworld and dungeon areas were strictly divided into different screens, but I

find it helpful on the tabletop as well: there’s the World, which includes many

Regions, which each in turn have many Points of Interest, which themselves have

Rooms.

Most campaigns will include only one world,

and even if campaigns include multiple, they tend to each only have one Region.

In Star Wars, for example, the

concept of a “planet” and a “region” tend to be synonymous—Tatooine

is a desert, Hoth is a tundra, the moon of Endor is a forest, and so on. Naboo

is pretty unique in this context in that it effectively has two regions—an

ocean and a forest. In D&D, a great example of a multi-world setting is Planescape, which features planes such

as the Plane of Fire and the Outlands (which are often thought of as single-region),

as well as several major metropolises, most famously Sigil.

“Regions” in a typical D&D

world would include a specific forest, or mountain range, or desert. “The

Westwoods” would be a single region, “forests, generally” is

not. Region-level travel is typically measured in days or weeks, rather than

rounds or minutes, so GMs tend to lean heavily on procedural content generation

like random encounter tables to sprinkle these days or weeks with notable

events and discoveries along the way. These random rolls accompany bespoke

content created manually by the GM, such as a monster selected directly from

the Monster Manual, or pre-written

NPC encounters.

Each Region is a container for one or more

points of interest. These are things like magical springs, taverns, washed-out

bridges, and even entire dungeon complexes. In a video game like Final Fantasy or Baldur’s Gate, in an adventure site, the game would zoom in to a

level where you would actually see your characters walking around where you

direct. When using an adventure module, points of interest will include maps to

a scale measured in feet, rather than miles. At their most modest, a point of

interest can be a simple skill challenge (how will we cross the river with the

bridge washed out?) or comment “on the fifth day of travel, you see Lonely

Mountain crest on the horizon”), and at their most complex, a point of

interest is multi-session crawl, such as the entire Caverns of Thracia.

When people try to think about a city as a

dungeon, they’re really saying that a city is on par with a point of interest

In the diagram above, Mos Eisley (a city)

is a Point of Interest (a dungeon-scale site) divided up into buildings (which

are Room-scale locations; important ones would have their own keyed entries

like a dungeon’s room would). Elsewhere in the same Region (the Deserts of Tatooine)

is the moisture farm that Luke grew up on, which is also divided up into rooms,

such as the room Luke works on C-3P0, and the kitchen, where blue milk is consumed.

In this view, streets are akin to the hallways of a dungeon, and buildings are

like rooms. Every building, street, and lamp post is important, as they might

provide cover in a shootout or an obstacle in a chase.

By similar logic, when I argue that a city

is a forest (that is to say, a region-level area), I’m saying that the city

should be bumped up one step on the scale:

If Mos Eisley is bumped up to be its own

region surrounded by the deserts of Tatooine,

rather than inside the deserts of Tatooine,

it leaves more room for fleshing out its own components, which are dungeon-tier

Points of Interest now. Travel around Mos Eisley is handled in an abstract way with

a die roll for random encounters every hour or so (*rolls* “uh-oh, you’ve

been pulled over by Stormtroopers!”) rather than dungeon-crawl-esque

movement (“hrm, should we take a left or a right at the bantha?”)

When running an adventure in a city, don’t

sweat the details. It doesn’t matter what street the party has to take, and it

doesn’t matter how many minutes or rounds it takes to get there. By ignoring

these details, you aren’t giving up or giving in—you’re being efficient. You

wouldn’t describe every tree in a forest and wouldn’t call for a Climb check

for every hill; similarly, you don’t need to talk about or think about every

road and intersection.

If, for some reason, it is critically important

that building A (say, the Temple of Heironeous) is directly across the street

from building B (say, the temple of their hated enemy, Hextor) for narrative

reasons, then note this in their keyed descriptions. In many ways, the temples

of Hextor and Heironeous together would function as a single larger Point of

Interest. Similarly, in Terry Pratchett’s Men

at Arms, it is critically important for murder-mystery reasons that the Guild

of Assassins shares a wall with the Guild of Fools. However, what isn’t important is how many left turns

and right turns it is to get to the Guilds of Assassins and Fools from the watch

house. The distance between the watch house and the guilds is abstract (because it doesn’t matter

beyond broad generalities), while the distance between the two guilds is concrete (because it really matters).

Enough

A city map is only one layer to the

adventure, and is not, in itself, sufficient to run an urban adventure—but it’s

a start. Various books, such as the third-edition-era Cityscape, provide advice for creating cities at the regional level, that is, drawing major

roads and creating districts and neighbourhoods and such. This part’s easy and

fun, but it’s the next step (“okay, what do we actually do here?”) where I as the GM start

to panic, and, I’d be willing to bet, other GMs do as well.

What’s missing is dungeons. Points of Interest. It’s not enough to simply say

“ah, this is the Hive, it’s full of scum and villainy,” you have to say

to yourself “in the Hive is the Mortuary, which is a dungeon.” It’s

around that point that it is appropriate to grab the graph paper and start drawing

hallways and rooms and chests and traps—classic D&D stuff. Once you’ve got

your dungeon, it’s a simple matter of hooking the players, which is no

different than with a wilderness dungeon—rumours, mysterious letters, job

postings, and all the usual tricks can be used freely here.

Making an urban dungeon is very similar to

a wilderness dungeon, but you have one or two extra considerations: the

authorities, and the peasants.

Law Enforcement

One way or another, you need to keep the

pesky authorities out of the dungeon. Either they’d arrest the PCs, or they’d

arrest the vampires, and both ways are boring. There’s loads of ways to pull

this off, but here’s a few examples:

PCs are the authorities (either

full-time, like a fantasy SWAT-team, or are hired in as mercenary contractors)The

law enforcement are the monsters (i.e., the vampires or whatever have

mind-controlled or corrupt guards protecting their ‘dungeon’)The

law enforcement has no authority in the dungeon (which, like the Mortuary

earlier, is ruled by a powerful faction, in this case, the Dustmen of Sigil)There

is no centralized law enforcement (each district is controlled by its own

faction, gang, or guild, and whoever has local authority has no interest in the

dungeon)

Torches and Pitchforks

If there really is a fully-blown dungeon

operating in a town, something has to have prevented the local populace from

rising up against it, torch-and-pitchfork style.

peasants are cowed into submission (the “seemingly-ordinary village in

Transylvania” solution)The

peasants don’t know about the dungeon (the “cult in the sewers”

solution)The

peasants are in on it (the “Hot Fuzz” solution)“I Go Find Some

Berries or Something”

In a forest, if the party is low on food

and a player says the above sentence, no GM would just let them find berries. Berries represent—quite literally—a free

lunch, which proverbially doesn’t exist. At the very least, a skill check is

needed, and a low enough roll provides the possibility of danger (consuming poisonous

berries, being attacked by giant owls on the way, that kind of thing). There are free berries out there in a forest

for anyone to pick, but finding them requires certain skills and the accepting

of a degree of risk.

As a GM, keep an eye out for the “free

berries” of the city. In the modern world, we’re used to municipal

governments providing many services free-of-charge. Fire fighters and police

can be called in an emergency, there are charities and food banks if you’re

down on your luck, and (depending on your country and insurance situation),

hospitals and clinics can be gone to if you’re sick or injured. Our phones can

find these resources for us and provide easy-to-follow directions to their

doors.

In the world of D&D, things are not so

simple. Standing police forces are a modern invention; in the past in many

cities, guilds organized militias to patrol certain areas at night if at all.

Large stretches of the city might have no law enforcement at all, or (for

example) perhaps on Tuesdays—the night that the infamously corrupt Shoemaker’s

Guild patrols the streets, lawlessness might be preferred. If you’re sick or

injured, it’s up to you to figure out which doctor is legitimate and which is a

scammer. A PC can’t just walk into the office of a good doctor any more than

they can just go pick some healing herbs in the woods—both require local

knowledge, experience, and/or a skill roll.

Sir Poley's Blog

- Sir Poley's profile

- 21 followers