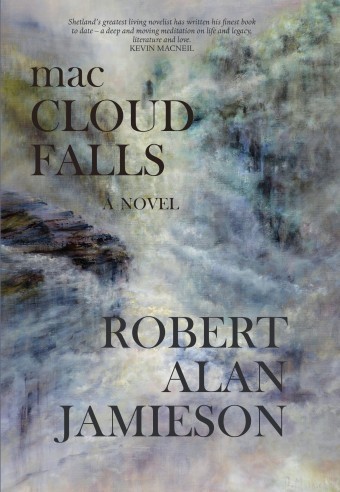

Review of "macCloud Falls" by Robert Alan Jamieson, pub. Luath Press 2017

Instead, she had his written account of the time they'd spent together in Vancouver. But it wasn't what had really happened. Some of it she remembered, some of the things they'd done, even some of the words that he'd put in her mouth. But the names were wrong, the details were wrong. If she had become the story, he had told it his way and it wasn't how she would have done it. His story.I don't recall writing a review, before, in which even to mention the real name of one of the main characters would be a spoiler. But it would, if I named the woman who thinks the above, because nearly everyone and every place in this novel has at least two names. Even the protagonist, Gilbert Johnson, is called Gil by some, Bert by others, and the odd typography of the title is because the place its inhabitants now know as Cloud Falls was once called MacLeod's (soon misspelled MacCloud's) Falls after an early settler (and would, before him, have had an indigenous name, now lost). The point being that naming is a form of owning and changing, and that everyone tells a story his or her own way, and makes a different tale out of it.

Gil is an antiquarian bookseller from Edinburgh, also the kind of writer who is always going to write a book but never quite does. He has recently had radiotherapy for throat cancer, and while it seems to have worked, it has made him far more conscious of mortality and spurred him to finally research a piece of family history – he thinks a man called James Lyle, who emigrated from Scotland to Canada and became well known as an ethnographer and political activist, may have been his grandfather and has come to find out. Lyle, by the way, though fictional, is based on an historical character, James Alexander Teit, and if you say the two surnames together it will become clear by what impish process Teit has been fictionalised as Lyle.

Once in British Columbia, Gil becomes very caught up in the First Nations history of Cloud Falls, where Lyle lived with his first wife, whom Gil has previously known as Lucy, the English name she was given by missionaries, but whose real name, he now finds, was Antko. She was also the source for the research Lyle did on First Nations culture, and to the indigenous people Gil meets, she was the story and Lyle her scribe.

However, though Gil certainly makes plenty of notes for the book on Lyle, the one he actually finds himself writing concerns himself and a woman he met on the plane. She too is a cancer survivor – they call themselves radiation twins – and follows him to Cloud Falls out of concern that he may be having suicidal thoughts (he is, though it was never quite clear to me how this meshed with his new-found determination to write and to spend his time less tamely than he had before the cancer).

As the book progresses, he begins to care less for the past than the present, and Lyle's story starts to fade. There are questions we never get answers to, not because they don't exist but because Gil has ceased to care about them as much. I must admit, being myself a history nut, I had got quite involved in Lyle's story by then and rather regretted this; when Gil, having seen a bigger waterfall, thinks of Cloud Falls; "It was nothing like as tall as Helmcken, not nearly so impressive" there is a little shock of betrayal. But in narrative terms, the shift is completely justified.

Narrative devices are important in this novel: people read each other's journals and fictions, whole sections appear to be told by an outside narrator, until the next section makes it clear that we have in fact been reading Gil fictionalising his experiences again. The only such device that didn't work for me was the Appendix to Gil's book proposal, which is a history of the settlement of the area in the form of notes. The woman, reading this, gives up after 9 pages, feeling "it was too much to take in piecemeal". It certainly was; I had started skimming some time previous. In a history book it might have been fascinating, but one reads fiction in a different vein. The information it conveys is very relevant to the theme of story and how each narrator changes it, but I don't think it was best conveyed in this way at this length.

The other thing I must note is the many typos not picked up in proof. For some reason, most of them involve missing definite and indefinite articles – eg "he stood for moment" (p143), "some of regulars" (p111), "she peered into room" (p191), but I stopped listing because there were so many, as if some compositor had a down on "the" and "a". Odd. But it should not detract from an absorbing, many-layered and thought-provoking read in which no person, place or event turns out to be quite what we thought on first acquaintance.

Published on September 15, 2017 05:37

No comments have been added yet.