A Czech Astronaut’s Earthly Troubles Come Along for the Ride

Credit

David Jien

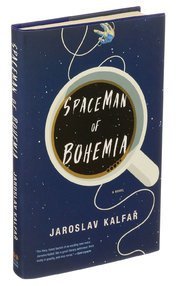

SPACEMAN OF BOHEMIA

By Jaroslav Kalfar

276 pp. Little, Brown & Company. $26.

In December 1972, as Apollo 17 flew toward the moon, one of the astronauts (no one seems to remember who) picked up one of the mission’s 70-millimeter Hasselblad cameras and took the first-ever complete photograph of the Earth. The so-called blue marble picture became possibly the most widely distributed image in history. It is credited with a profound shift in global environmental consciousness, the view of Earth against the absolute darkness of space giving a simple form to our sense of the planet’s beauty and fragility, and our absolute dependence on its ecology.

The same era, the golden age of manned spaceflight, also saw a cultural preoccupation with the extraordinary psychological situation of the astronaut. What did it feel like to find yourself outside Earth’s life support system, far from the fellowship of other humans? The flip side of the profound loneliness of space is the tantalizing possibility that by transcending physical boundaries, spiritual forms of transcendence will follow. Figures like David Bowie’s Major Tom, the spaceman who refuses to come back to Earth in the song “Space Oddity,” and Bowman, the astronaut in “2001: A Space Odyssey” who is pulled by the alien monolith across vast reaches of space and time, are only the most prominent representatives of a genre that, judging by the success of recent Hollywood movies like “Gravity” and “The Martian,” retains its enduring fascination. The lonely astronaut can be a modern Robinson Crusoe, a white-knuckled survivalist, an existential freak and seer. For J.G. Ballard, who used the morbid figure of a dead astronaut orbiting the Earth in several short stories, the corpses become monuments, Ozymandias-like ruins that condemn the spiritual and intellectual failure of the military-industrial space program.

Jakub Prochazka, the Czech hero of Jaroslav Kalfar’s zany first novel, “Spaceman of Bohemia,” is an astronaut who has left a lot of baggage back on Earth. He is the shining hope of an entire nation, the biggest celebrity in his home country, so excruciatingly aware that his endeavor “will carry the soul of the republic to the stars” that he refuses water before liftoff lest he should inadvertently urinate and “the purity of my mission” become “stained by such an undignified gesture.”

Photo

Credit

Patricia Wall/The New York Times

The reason the Czech Republic is launching a manned spacecraft is the arrival of a strange comet that has “swept our solar system with a sandstorm of intergalactic cosmic dust.” A cloud, named Chopra by its Indian discoverers, now floats between Earth and Venus, turning the night sky purple. Unmanned probes sent out to take samples have returned mysteriously empty. Likewise a German chimpanzee has returned to Earth with no information save the evidence that survival is possible. The Americans, the Russians and the Chinese show no sign of wishing to risk their citizens, so the Czechs have stepped up, with a rocket named for the Protestant reformer and national hero Jan Hus. At many points in the novel, Kalfar sketches key moments in Czech history, and the very premise of a Czech space mission is clearly a satire on the nationalist pretensions of a small post-Communist nation. Financed by local corporations whose branding is placed on his equipment, Jakub is the epitome of the scrappy underdog, grasping for fame by doing something too crazy or dangerous for the major players.

Continue reading the main story

The post A Czech Astronaut’s Earthly Troubles Come Along for the Ride appeared first on Art of Conversation.