I'M A PLOTTER, THANK YOU VERY MUCH

By Francine Mathews

During a panel at a writer's conference a few years back, the lovely and talented moderator, Catriona MacPherson, posed her final, devastating question to each of us:

"Plotter or Pantser?"This needed no explication for veterans of the conference scene. Plotters are the anal-retentive, overly-anxious types who have control issues about everything from the weight of the paper stock in their printers to the cover images forced on them by publishers. Their hapless characters move through a predetermined landscape to inevitably awful ends.

Pantsers are the creatives, who burn incense and scarf chocolate while awaiting the descent of the Muse. They follow the whims of their astrally-inspired synapses and are as astounded as their readers by their novels' conclusions. Endings, like life, should just...happen...somehow.

This is also known as writing organically. The theory being that things grow as they should, if you just throw enough shite at them.

I admire these writers.

I am not one of them.

Ask me to "pants" and I'd take to my bed with a hot toddy and acute vertigo. Without my cherished outlines, I'd never write a word. Easier by far to summit Everest in stilettos.

I wrote my first novel on a dare from my husband. He gave me a powerful incentive: If I could craft a beginning, middle and actual end of a book--not just, say, the first seventy pages that most of us find so exciting--we'd sit down and talk about me quitting my real job. I was tired of wearing stockings at eight a.m. I wanted to set my own schedule and work from home. I was motivated. I figured that if I were going to spend the next year mentally inhabiting a fictional world, it had better be one I enjoyed--so I wrote a classic detective novel set on Nantucket. It was purely an exercise, and like most first novels, it was far from perfect. But an agent accepted it and scored a two-book deal with a major publisher. I never went into an office again.

What worked for me?

Having a road map.

Imagine you're setting out on a journey. Leaving Las Vegas, for the sake of argument. In a month or so, you have to be in New York for the next phase of your life. You could sleep anywhere in between--Columbus or Yuma, Oshkosh or Greenville--but you're traveling with the unswervable goal of reaching Manhattan. The road gives you freedom to explore, of course--you can take any exit that tantalizes and go down that street for a while--but if it proves a deadend, you may double back, take a shortcut, reroute and get on the right track. And a month later, there's the sign for New York--as you expected.

Imagine you're setting out on a journey. Leaving Las Vegas, for the sake of argument. In a month or so, you have to be in New York for the next phase of your life. You could sleep anywhere in between--Columbus or Yuma, Oshkosh or Greenville--but you're traveling with the unswervable goal of reaching Manhattan. The road gives you freedom to explore, of course--you can take any exit that tantalizes and go down that street for a while--but if it proves a deadend, you may double back, take a shortcut, reroute and get on the right track. And a month later, there's the sign for New York--as you expected.That's what a plot outline does for your writing.

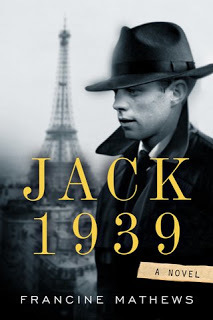

I always begin a novel with a great idea--a simple notion that intrigues and compels me. Fact: Jack Kennedy took off half his junior year at Harvard and traveled alone, from London to Moscow, as Hitler prepared to invade Poland. Fiction: What if Jack were also spying for Roosevelt?

Then I do a ton of research. I educate myself on the time period and the circumstances so that I'm confident I can tell a good story. I figure out the arc--the personal growth my main character has to endure by struggling with the conflict I hand them. Most importantly, I start my plot outline with the story's end.

This is critical. This is New York. The point of every road trip: our destination.

In the case of JACK 1939, the book had to conclude with Hitler invading Poland--and Jack Kennedy returning to Harvard to write his senior thesis. But that's merely the obvious structure of a novel set in a specific life and time period, the constraint of historical fiction. I knew this was really a coming-of-age story about a chronically ill young man, the black sheep of his family, who felt he had failed at everything he'd tried to accomplish in life. He'd lived in the shadow of his far more successful older brother and was convinced he'd be dead by thirty. So the psychological conclusion of the book would be far more important than the historical end:

Jack proves FDR was right to trust him. And he was right to have

faith in himself. He has lost the woman he loves and some respect for his father, but he's learned to trust his own courage and intelligence. Despite the limitations of poor health and reckless impulses, he has confronted profound evil and survived atrocity. He has fought the Good Fight. What he's learned on his Hero's Journey is critical to the man--and President--he becomes.

faith in himself. He has lost the woman he loves and some respect for his father, but he's learned to trust his own courage and intelligence. Despite the limitations of poor health and reckless impulses, he has confronted profound evil and survived atrocity. He has fought the Good Fight. What he's learned on his Hero's Journey is critical to the man--and President--he becomes.It's fundamental to know how your story begins. But knowing how it ends allows you, as a writer, to step out confidently on the writing road. It may even allow you to dabble in "pantsing," as you follow your characters down uncertain streets, then haul them back onto the straight and narrow. You're less likely to end up with your wheels in a ditch, waiting for a tow.

So here's a question: Can you tell whether a writer is a plotter or pantser by reading their books? Does it matter?

Cheers--

Francine

Published on September 29, 2016 19:00

No comments have been added yet.