Wounded Knee was a Battle Not a Massacre–Sam Russell Interview

Col. Sam Russell (currently assigned to the U.S. Army Peacekeeping and Stability Operations Institute at Carlisle Barracks, PA), however, has proven previous accusations wrong with a book which compiles news stories (including eye-witness accounts) about the situation on the reservation.

The stories begin a few months prior to Dec. 29, 1890, when the battle occurred, to a few months following.

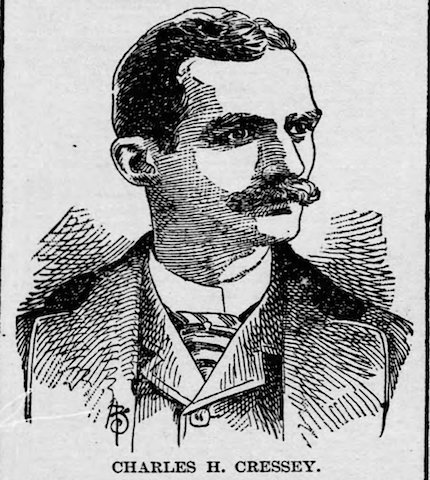

The news stories were written by Charles H. (Will) Cressey for The Omaha Bee.

Cressey was a witness to the battle, as were two other journalists, who

reported the same facts.

reported the same facts.The book is titled Sting of the Bee: A Day-By-Day Account of Wounded Knee And The Sioux Outbreak of 1890–1891 as Recorded in The Omaha Bee.

Father Francis Craft, a part-Mohawk Catholic priest, was also a witness, and Fr. Craft verified what Cressey and other reporters wrote.

Full disclosure, Sam has included a thank you to me in his introduction just because I read his manuscript and had a few editing suggestions.

He didn’t need to thank me. He did a fine job with this badly-needed corrective.

Sam, Omaha Bee reporter Will Cressey wrote the dispatches you quote in your book (and did an admirable job), and was present at the battle. He reported Wounded Knee as a battle in which the Sioux shot first.

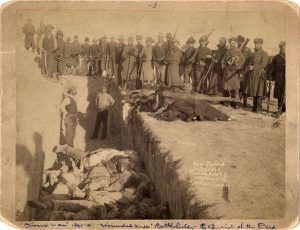

Burying Sioux bodies

Cressey wrote the Seventh Cavalry soldiers were disarming the Indians and surrounded them while others searched their tepees for weapons.

“About a dozen of the warrior had been searched when, like flash, all the rest of them jerked guns from under their blankets and began pouring bullets into the ranks of the soldiers who, a few minutes before, had moved up within almost gun length.

“Those Indians who had no guns rushed on the soldiers with tomahawk in one hand and scalping knife in the other…”

Burial party, Wounded Knee

Cressey wrote he was standing behind the Indians, close enough to touch them and the Indians “must have fired a hundred shots before the soldiers fired one.”

The Indians subsequently got away to the hills where the battle continued.

Unfortunately, when the Indians first fired, the bullets which failed to initially find a target passed the soldiers and hit the Sioux women who were standing behind the soldiers.

Robb: What did the other two reporters who witnessed the battle write about it?

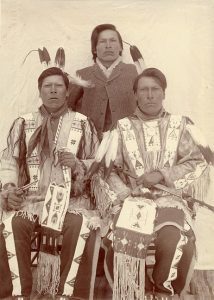

Brothers, (left to right) White Lance, Joseph Horn Cloud, and Dewey Beard, Wounded Knee warriors; Miniconjou Lakota

Russell: The three reporters that were present at Wounded Knee when hostilities broke out were Will Cressey of the Omaha Bee, Charles Allen of the Chadron Democrat, and William Kelley of the Nebraska State Journal, all were correspondents from Nebraska.

Not surprisingly, their sympathies were aligned with the settlers and residents of that state, and their three accounts were not all that different.

Kelley’s portfolio of articles was published in 1971, Pine Ridge 1890, and Allen wrote an autobiography that was published in 1997, From Fort Laramie to Wounded Knee, which included his article describing the battle.

There was a fourth reporter, Thomas Tibbles of the Omaha World Herald, who was at Wounded Knee the morning of the battle, but he departed early and wrote that he could hear the gunfire and cannons on his trip back to the Pine Ridge Agency.

Tibbles was married to an Omaha Indian, Bright Eyes, and the two of them offered the closest thing to a Native American account of the events surrounding the outbreak.

After the initial melee around the council circle concluded and the fight moved toward the ravines, Cressey, Kelley, and Allen retired to the shelter of Louis Mousseau’s trading post at the Wounded Knee Creek crossing adjacent to the cavalry camp and began writing their articles.

January 1891, Albumen Cabinet Card Photograph of a small log cabin behind the Post Office at the Pine Ridge Agency in South Dakota – the location from which the first news reports about Wounded Knee were written. In this photo we see U.S. Marshall George Bartlett, writer / archeologist / anthropologist, Warren King Moorhead, an Indian Police sentry in full uniform and a third, unidentified white man believed to be Louis Mousseau who lived in the cabin and ran the Post Office / Store.

They had little time to write and still get their dispatches transported to a telegraph operator and submitted in time to make the evening editions. Unfortunately, that meant that none of the reporters witnessed that portion of the fight that included pursuing Indians up the ravines and into the hills.

Kelley, who won the honor by lottery of having his dispatch transmitted over the wires first, wrote, “All of a sudden they [the Indians] threw their hands to the ground and began firing rapidly at the troops, not twenty feet away. The troops were at a great disadvantage, fearing the shooting of their own comrades.”

Said to be survivors of Big Foot’s band

As Kelley recorded his perspective of the fight, the sounds of skirmishing rang out in the distance. He went on to write, “To say that it was a most daring feat, 120 Indians attacking 500 cavalry, expresses the situation but faintly. It could only have been insanity which prompted such a deed.”

Gen. Nelson Miles

Kelley concluded his article with, “Before the night I doubt if either a buck or squaw out of all Big Foot’s band will be left to tell the tale of this day’s treachery. The members of the Seventh Cavalry have once more shown themselves to be heroes in deeds of daring.”

Allen’s article was less opinionated than that of Cressey and Kelley. Describing the opening of the battle, Allen wrote, “They [the soldiers] had proceeded to disarm but some eight or ten of these [Indians], when the brave who had been inciting them jumped up and said something and fired at the soldier who was standing guard over the arms that had been secured. The first gun had no sooner been fired than it was followed by hundreds of others and the battle was on.”

Robb: Cressey reported many Sioux women attacked soldiers at the battle and the soldiers were forced to shoot them. Was Cressey correct?

Russell: There certainly were a number of firsthand accounts that detail Lakota woman and teenage boys arming themselves and fighting back against the soldiers.

Once the first shots rang out, the struggle was fight or flight, with examples of Indian men, women, and children doing both.

Some White accounts show that the soldiers were conflicted as to whether they should or could fire on women and children who had chosen to arm themselves and fight.

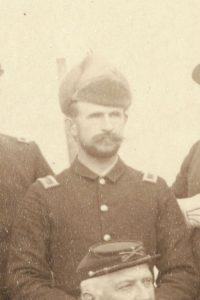

Second Lieutenant Thomas Q. Donaldson, Jr., C Troop, 7th Cavalry, present at Wounded Knee

Second Lieutenant Tommy Tompkins detailed one such incident in his testimony at General Miles’s investigation of Wounded Knee. “One of these mounted squaws was armed and fired on our line, and one of the men said then ‘There is a buck.’ And I said ‘No, it is a squaw, don’t shoot on her,’ and he said ‘Well, by God, Lieut., she is shooting at us.’ He did not fire at her.”

Robb: I was for many years a reporter and believe Cressey did an excellent job. Do you agree?

Russell: Given the period in which Cressey reported, and the newspaper for which he wrote, I believe he did an outstanding job.

Certainly his employer believed he did. He attempted to verify the myriad rumors that swirled around the agency, but, failing that verification, he still willing reported such rumors. He interviewed all comers, including Indians, particularly if they were considered hostile, and he at least presented their own words, even if it was through the lens of his own world view. That being said, Cressey’s bias is glaringly apparent.

To be fair, one can see such bias in news reporting today.

One certainly would expect to see a very different perspective from The New York Times versus the Wall Street Journal, or Fox News versus MSNBC.

Ghost dance

Moreover, one would not expect to see an Iraqi or Syrian perspective regarding the conflict in Southwest Asia from an American news outlet.

Certainly, if there were a Lakota newspaper reporting from Pine Ridge, the accounts would be far different than those of Cressey and his peers. Still, I believe his reports are relevant, and an important historical record, as they provide the context in which Nebraskans viewed the outbreak of 1890-1891.

Robb: What happened to Father Craft, who also witnessed Wounded Knee?

Russell: Father Francis M. Craft was a very interesting witness, in that he was unfamiliar with the soldiers at Wounded Knee, albeit he was a strong advocate of the Army.

Father Craft

Many contemporary historians write off all of the testimony that 7th Cavalry and 1st Artillery officers provided with the guise that they were lying to cover up their dastardly deeds and protect their inept commander. I find this astounding, as the documentation for Wounded Knee is substantial, taken under oath, provided within days of the battle, but largely ignored by present historians.

Father Craft’s empathy lay entirely with the Lakota, to the point of directing that his body be buried with the Indians in the trench at Wounded Knee if he died of his wounds. He was part Indian; his great-grandfather was a Mohawk.

(Fr. Craft) vociferously blamed the Indian Bureau for all the ills the Lakota suffered, and early on recognized those ills–abject poverty, misery, and starvation–as the root cause of all the turbulence in Nov. and Dec. 1890.

Craft was at Wounded Knee to serve as an interpreter, as a friendly face known to the Lakota through his last ten years of missionary work, and to convince the warriors that they would be well cared for if only they peacefully surrendered their weapons.

He was positioned between the warriors and the cavalry at the opening volley. He was, according one of his later accounts, shot by soldiers and stabbed by a Brule.

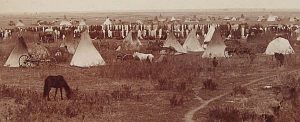

Ghost dancers

Yet from his perspective on the battlefield, Fr. Craft faulted the Lakota for initiating the hostilities, for continuing to resist, for indiscriminately firing on their own village situated directly behind a troop of cavalry, and lauded the actions of the cavalry in trying to spare the lives of women and children, to the point of taking greater casualties themselves than if they had just wantonly and mercilessly shot down all of the Indians.

Fr. Craft, who was not afraid to rattle cages and was very vocal on what he believed to be the truth, provided a deposition that corroborated the soldiers’ accounts of Wounded Knee.

Moreover, he was recovering from his wounds in the Catholic Church, not the army field hospital, so was not privy to the post-battle banter and collaboration, so to speak, that occurred among the soldiers prior to giving testimony. He provided a similar account to Eli Ricker, but the judge seemed to not pay much heed to Fr. Craft’s version of events.

In addition to his sworn deposition, Fr. Craft gave a lengthy description of Wounded Knee in Feb. 1892 that is recorded in At Standing Rock and Wounded Knee, by Thomas Foley.

Foley has produced two good reads on Fr. Craft. A Quote from Foley in his closing paragraphs I think is on the mark, “Proponents who would enshrine Wounded Knee as the iconic epitome of Native American victimization diminish the heroic stand taken by Big Foot’s warriors.” (Foley, 318)

Dewey Beard’s account of his exploits at Wounded Knee are singularly impressive and unquestionably heroic… and account, in part, for why the 7th Cav. continued the battle up the ravines, to suppress such fierce resistance.

Fr. Craft recovered from his wounds, and continued his work among the Lakota. He was an energetic and visionary man, whose efforts were thwarted at every turn, even by his own Church. He was too vocal and created some very powerful and politically connected enemies along the way. Perhaps his efforts would have blossomed if he had allied himself with St. Katherine Drexel.

ghost dance

Ultimately, his twenty years of work among the Lakota bore little fruit, and he settled into a small parish in Pennsylvania until his death in 1920.

Robb: Cressey was clear the Indians were starving and plainly stated the shortage of rations caused the uprising on the reservation. Why did that situation exist and was it remedied?

Russell: There were a number of factors that caused the dire circumstances at the agencies. Drought had wreaked havoc on crops in the Midwest in 1889 and 1890. The reservation lands were not suitable for substantial farming, and even the favorable farming lands in Nebraska and South Dakota were greatly affected by the drought conditions.

Congress decided to wean the Lakota off government rations by cutting back on their annual allotment with the expectation that the Indians would become self-sustaining only if pushed in that direction.

The government purchased the designated allotment of beef on the hoof by the pound, but by the time the cattle were issued to the Indians, each steer had lost from 20% to 40% of its body mass, leaving the Lakota to deal with the shortage.

The Indian Bureau believed the reported numbers of Indians on the reservations were inflated, and conducted a census in 1890. This census reduced the population count, and thus reduced the allocation of rations. A measles epidemic swept through the reservations in the summer of 1890 with a high mortality rate, which likely was exasperated by the poor quality and scant quantity of the government rations.

While the Ghost Dance was not meant as a protest per say, the wide media coverage that it garnered brought the plight of the Lakota to the attention of Congress and the American people.

In that context, the Ghost Dance did have a positive impact on the Lakota, as the government took steps in late

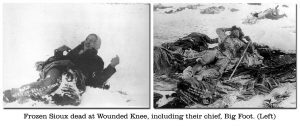

Wounded knee dead

November and December 1890 to correct the poor rations.

The Indian Bureau’s efforts to remedy the situation—only after pressure from the Army and negative publicity in the media—were complicated when the “hostile” bands scattered over 3,000 head of cattle from the government herd at Pine Ridge. The steers that these bands were able to rustle sustained them in their stronghold in the Badlands, which inflamed the crisis and allowed it to continue through December and into January.

Robb: I assume the Army could have brought overwhelming force against the Sioux, but chose not to. Why not?

Russell: President Harrison’s instructions to the War Department and General Miles was to protect the agencies and resolve the crisis without bloodshed, if possible.

Said to be Ghost Dance shirt

General Brooke arrived at Pine Ridge at the end of November with a small contingent of forces expressly to protect the Pine Ridge and Rosebud Agencies. As more forces arrived, like the 6th Cavalry Regiment from Arizona and New Mexico, 7th Cavalry Regiment from Kansas, and 1st Infantry Regiment from California, Brooke had the ability to assume the offensive, which he at times seemed almost desperate to do.

He had even issued orders and had all forces (over 27 troops of cavalry a battery of artillery and 100 Indian scouts) in readiness to move on the Indians in the Stronghold of the Badlands.

General Miles delayed the order to move when Sitting Bull was killed precipitating many of his Hunkpapa followers to scatter toward the Cheyenne River. Miles was concerned that, if attacked, the Indians would break out of the reservations and kill settlers. He focused most of his attention on the Sitting Bull remnants and Big Foot’s band precisely because they fled from their reservations. His correspondence with Brooke shows him restraining his subordinate from assuming the offensive.

The Hotchkiss Gun fired into the Sioux camp at Wounded Knee Creek

As long as the Indians were not attacking settlers, General Miles was content to wait them out and cajole their leaders to return to the agencies. He hoped winter would set in and force the Indians to return.

Ultimately, General Miles’s patience paid off, and his strategy to encircle the Indians that refused to return to the agencies and slowly constrict his lines succeeded in bringing all the tribes back to the Pine Ridge Agency.

Following Wounded Knee, General Miles eventually resolved the outbreak without further bloody engagements, excepting White Clay Creek the following day, due largely to a hard lesson learned, by both Lakota and soldier alike, at Wounded Knee: that to force the Indians to relinquish their arms would result in conflict.

General Miles came up with the solution that ultimately worked, only after he had seen the result of Wounded Knee, namely, to have the Indian chiefs collect the firearms and surrender them, and to look the other way when they knowingly relinquished only a token few weapons.

War dance, 1890

Unfortunately, for all concerned, that lesson had yet to be learned on December 29, 1890.

Robb: What happened to the two Sioux babies adopted by whites, one by an army officer?

Russell: One of the infants died within days of being found on the battleground. The other infant was indeed  adopted. The child was christened Zintkala Nuni, or Lost Bird. Her adopted mother, Clara Bewick Colby, was a 44-year-old suffragist and wife of Brig. Gen. Leonard W. Colby, commander of the Nebraska National Guard.

adopted. The child was christened Zintkala Nuni, or Lost Bird. Her adopted mother, Clara Bewick Colby, was a 44-year-old suffragist and wife of Brig. Gen. Leonard W. Colby, commander of the Nebraska National Guard.

The Colbys were residents of Beatrice, Neb., and Mrs. Colby became the unwitting, albeit caring and affectionate, mother of an adopted Lakota infant found on the battleground of Wounded Knee when her husband secured the child during the campaign and brought home his small curio for his wife to raise.

Unfortunately for Lost Bird, the Colbys separated and eventually divorced.

Mrs. Colby struggled with poverty and raised her adopted daughter as best she could within her limited means.

Lost Bird, as a teenager, miscarried a child—rumored to be Gen. Colby’s.

She went on to perform on Vaudeville and married her co-star. Lost Bird died of syphilis at the age of 29. She struggled during her short life with her identity and was rejected by both White and Indian cultures.

In 1991, her remains were repatriated from California to the Pine Ridge Reservation at the Wounded Knee Memorial where she was buried next to the mass grave of her kinsmen that fell at Wounded Knee a century earlier.

Lost Bird as an adult

Renee Flood wrote a well-researched book, Lost Bird of Wounded Knee, detailing the lives of the Colbys and Zintkala Nuni.

Robb: Was there more than one Sioux Ghost Dance belief? Some seemed to expect Jesus Christ to appear again and restore them to a pristine wilderness.

Russell: It took months, if not years, for the government to determine exactly what the Ghost Dance really was, how it started, and how it spread so rapidly and expansively among almost every tribe of the Midwest.

James Mooney’s anthropologic work for the Smithsonian was the first real in-depth study of this phenomenon, and really was the first historical look at the root causes of Wounded Knee from an Indian perspective. There were similar instances during the nineteenth century of Native tribes that adopted a messianic religion with similar overtones, e.g. resurrection of dead warriors and family members, return of buffalo and other wild game, removal of Whites, resistance to Americanization, etc.

Hope Springs Eternal, by Howard Terpning

I included one article that touched on this topic detailing Smohalla of the Wanapams. There were several other articles printed in the Omaha Bee during that winter that delved into cases of messianic religions among American Indians. It was certainly an aspect of the 1890 outbreak that interested the readers of the Bee.

Robb: What happened to the white man who claimed to be the Christ the Indians were waiting for?

Russell: Albert C. Hopkins was one of the stranger characters of that winter’s outbreak, and served almost as comic relief for what was otherwise a very serious, and ultimately, deadly series of events.

Officers serving at Pine Ridge reservation

Cressey described Hopkins as a “little daft,” which was an apt characterization. Hopkins was the founder and president of the Pansy Society of America. He lobbied Congress to recognize the pansy as the national flower, and even received support to redesign the U.S. Flag by arranging the white stars into the shape of a Pansy.

The design appeared in several papers, but ultimately the Congressman who introduced the bill also realized that Hopkins was a “little daft” and dropped support for the bill after being ridiculed in the press.

Hopkins died in 1904 in Canton, S.D. His death announcement was titled “’Pansy’ Hopkins Dead” and explained that, “His mind has not been right for some years.” Hopkins was a Union veteran and served in the 11th Wisconsin Infantry Regiment during the Civil War.

Sam Russell

ArmyAtWoundedKnee.com.

The post Wounded Knee was a Battle Not a Massacre–Sam Russell Interview appeared first on .