Curiosities

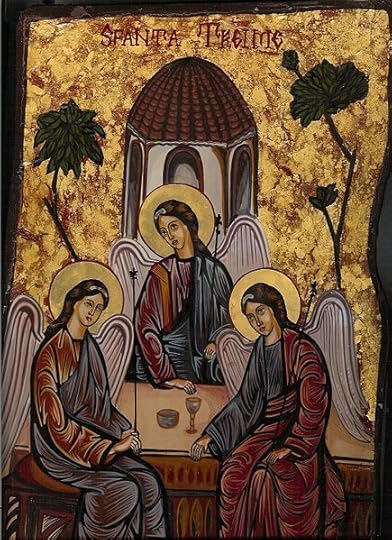

Romanian icon of the Trinity

At no other time than Holy Week is the divide between the secular and sacred worlds quite so apparent. Outside, Easter is egged, pastel, chocolate-coated, and hopping, but unlike Christmas, it's not a general holiday with ritualized religious overtones: gift-giving, gathering of far-flung families, remembering those closest to us.

Although I guess the world thinks otherwise (the world makes many assumptions), for me the focus of Holy Week is not on blind belief in every detail of a repeated biblical story. It's not, for me, about eternal life and a savior dying for my sins: I've never believed in or accepted the doctrine of atonement, and while I think consciousness may continue, reward and punishment in the afterlife don't motivate me nearly as much as what I see in the here-and-now.

However, the content and intensity of the human story, the political story, and the spiritual questions they ask, heighten an internal struggle: a deliberate engagement with my own mortality and that of those closest to me, as well as the culmination of weeks of trying to shine a light into the hidden corners of my life: my shortcomings and blind spots, ingrained patterns of behavior, my hopes and plans for change, a desire to be a better and more giving and loving person in a world filled with suffering and injustice. Tonight, Maundy Thursday, we'll hear "the new commandment" Jesus gave his disciples, who, on the eve of his death, he called "my friends:" "Love one another as I have loved you." Such simplicity. There's not much harder to do than that.

I like Lent, and I like Holy Week, because the light that comes through is always stronger than the darkness - and I think that's the point of actually observing a so-called penitential season. Muslims say the same thing about Ramadan. I'm grateful for this time set aside specifically for the purpose of reflection, change, and renewal: grateful because it actually works for me, and because even though I know I will fall back into old habits - who doesn't? - it feels like each year a little progress is made. A few more of the lessons and insight actually stick, and a little bit more of the intentional practice of self-observation -- and, paradoxically, forgetting myself and simply being -- becomes ingrained into everyday life.

For the past few years I haven't given up anything material, like chocolate or meat or the internet. I've avoided buying new clothes, and tried to remember to ask myself each time I reach for my wallet, "Is this really necessary?" but haven't been all that strict. This year I've focussed on a couple of particular questions about vocation, and tried to keep up an intentional daily practice of contemplation, accompanied with journaling, and to work on two specific behaviors: not complaining, and being cheerful even when I feel out-of-sorts, which has certainly been a challenge with the weather we've been having. I did the exact same thing last year and the year before that, so there's your proof of how slowly real change occurs! Over a very long time -- decades now -- I know I've become lighter, happier, clearer, and better able to cope with myself, with my relationships, and with the ups and downs of life. Many people have helped me, both directly and indirectly. But I attribute the greatest changes to the fact of having a spiritual life and practice.

--

Another gift is being in a community of others who are trying to do the same thing, whether they talk about it very much or not (and few find that particularly easy, except writers and clergy). We may know what we're about and why we keep at it in this particular way, but the world, increasingly, does not. That doesn't bother me except when I notice that we're being viewed as a curiosity, which happens often in a downtown cathedral. We are deliberately porous to the world; doors are open onto St. Catherine Street, the busiest concentration of shops and restaurants of both licit and illicit reputation in Montreal. tour buses discharge their passengers on our corner; we are right above an entrance to the metro and underground city, and on our steps there are always transients and beggars looking out and tourists looking in. People wander inside all the time. Some sit in a pew and listen or reflect, some light a candle. Most are respectful and quiet. A few walk through carrying their own attitudes along with their cameras and loud voices, no matter what's going on, and I watch them watching us - the choir - as if we were some sort of curiosity, an exhibit in a human zoo, which I suppose we are.

The other night at the conclusion of Compline, as we started down the chancel steps in semi-darkness for the silent recessional, a woman stepped out of her pew into the aisle and took a flash picture from only a few feet away from the first two choir members. We're photographed often, but usually not quite so brazenly. She turned out, later, to be part of a tour group from Spain. All right, I wondered, settling down: how many Africans and South American natives have danced in their feathers and jewelry for white travellers, or had their marriage ceremonies and funeral rites photographed and filmed as prizes to be taken home and exhibited to friends? Why should it be any different when we are now the ones participating in strange rituals that, a century from now, may no longer exist? (I hope this is not a complaint.)

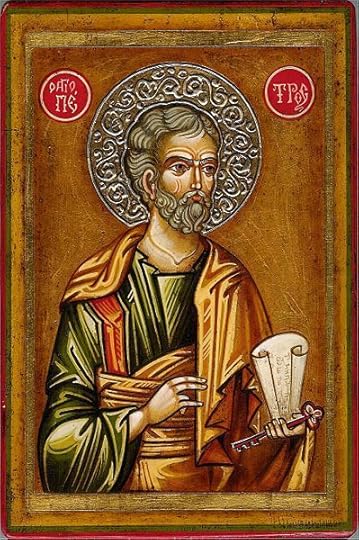

Romanian orthodox icon of St. Peter, who will deny his friend Jesus three times tonight.

This morning I passed by a Romanian Orthodox church in our neighborhood and noticed that the front door, usually closed, was open. So I went in. Stairs led down -- to a community gathering area, I suspected -- and up to the church, where I heard hushed voices. I went up, through another door, and into a warm sanctuary, wider than it was long, and sat down in a back pew. The walls were of wood. Painted Orthodox icons hung or stood everywhere: on the altar, on the walls, on the ceiling. There was one very precious icon of hammered gold and silver -- a Madonna and Child - with a painted or enameled face and hands but most looked relatively new. Several people holding small prayer books knelt in the pews and prayed, and over on the western side of the sanctuary, a priest in a brocade robe prayed with a woman who was, perhaps, giving a confession. His arm was around her and a purple stole lay over his shoulders and her head; as he prayed or spoke to her I could see her head nodding under the stole. In the front, bustling about the altar, three elderly women, dressed in full skirts and wearing kerchiefs, prepared the sanctuary for Easter. Huge pots of blue and pink hydrangeas had already been placed in tiers around the main altar, and the women raised and rearranged several large rugs piled atop a floral carpet with a large rose pattern. A stand of votive candles flickered red, gold, and green, and behind me in niches in the wall were trays of sand and thin tapers lit by worshipers. Although windows were open to the cool morning, lingering incense still perfumed the air.

The Byzantine and eastern European convergence was beautiful, almost intoxicating, in spite of the newness of the sanctuary - this was Canada, after all, and clearly the church of an immigrant community. The scene would have made an extraordinary black-and-white photograph. I wanted to take it -- for you -- but I did not.