David Boyle's Blog, page 24

January 18, 2016

Why don't they believe in competition any more?

Some years ago, I was commissioned to write an article about the future of food by the Environment Agency, since I had written a series of these fictional glimpses before. For some reason, that I now forget, I chose a future based on a kind of Lion-Witch-Wardrobe kind of world, where there was only one company that sold us everything. I called it TescoVirgin plc.

Some years ago, I was commissioned to write an article about the future of food by the Environment Agency, since I had written a series of these fictional glimpses before. For some reason, that I now forget, I chose a future based on a kind of Lion-Witch-Wardrobe kind of world, where there was only one company that sold us everything. I called it TescoVirgin plc.This turned out to be too controversial for my employers. It was naive of me to think otherwise, but I had enjoyed writing it.

I think of that article, which has been published in my short ebook The Age to Come , every few weeks now as the future I envisaged, that aspect of it anyway, seems to creep closer and closer.

My experience moving house 18 months ago, when I was unable to switch any of my services – not phone, nor electricity nor gas and certainly not internet – without infuriating problems, convinced me that the market had become seriously overconsolidated.

I thought of it again this morning listening to the head of Ofgen on the Today programme, saying much the same thing, but calling in aid the failure to cut energy prices not the appalling customer service.

I was wondering why this is and realise that it is often the most doctrinaire market fundamentalists who get appointed to these regulatory positions. And market fundamentalists think that prices are the only measure of anything.

In fact, it must be partly the fault of regulators that so many public services have built their customer service systems around a model that copes brilliantly with absolute normality, but for some peculiar reason can’t cope with small anomalies – like moving house.

What is most peculiar about the whole issue is that these are often privatised utilities, privatised because competition seemed to provide a better deal for customers – as it does – yet now consolidated so much that competition seems impossible.

The best example of this isn’t the electricity market, which is dominated by a handful of deaf, exhausting brontosauri without human emotion. It is the mobile phone market, especially now that the merger between EE and BT has cleared its regulatory hurdles.

That gives BT about a third of the mobile market, when the Office of Fair Trading believes that market distortion begins to creep in when a company builds up a share of over 8 per cent

Now we have the next merger before regulators in Europe, with 3 wanting to merge with O2.

The real question is why the market fundamentalists don’t believe in competition? Or perhaps more accurately, why they don’t think – despite a few centuries of evidence – that monopolies and oligopolies don’t fleece and patronise their customers.

The answer, as I’ve argued before, lies with Milton Friedman who taught that monopolies are not a serious problem. Because the Liberal voice has been muted in government circles, and – when it hasn’t been muted – it has forgotten the central pillar of Liberal economic thought: that monopoly is a kind of slavery. And a profit-making monopoly is an all-powerful beast, dedicated to its own survival.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on January 18, 2016 09:16

January 12, 2016

Mental education versus physical education

I have been reading the great unread classic autobiography of Victorian and Edwardian life, Frank Harris' My Life and Loves. It is vast and sprawling, part pornography, part political memoir, part self-help manual.

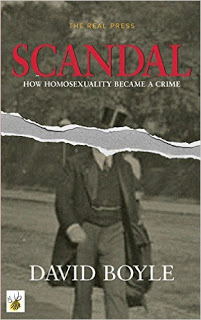

I found myself reading it when I was researching my new book Scandal , about the strange story of why homosexuality was criminalised in 1885, and Harris knew many of the people involved. It is bizarre and hard to put down (and not really because of the pornography, I assure you).

The trouble is that Harris is widely believed to have been a liar, and his first biographer chose the sub-title 'The biography of a scoundrel'. It doesn't help that he had extraordinary powers of recall, which means - for example - that most of the copious poetry he quotes in his autobiography are clearly taken from memory and therefore not completely accurate.

This is a pity because Harris really did know everybody in the 1880s and 1890s in London and beyond and what he remembers is worth remembering. The pornography meant that unexpurgated editions were banned until 1962.

By the fourth volume you begin to feel his concentration is flagging, only to have what is an absolutely gripping account of his investigation into the abortive Jameson Raid in 1895, which led to the Boer War and arguably the rift with Germany.

But I have learned something from Harris and it followed from his own conviction that he was too short to be a great athlete. He decided he had to develop in himself the physical and mental control he needed to succeed. These are detailed at great length. Extraordinary self-confidence clearly helped.

But it made me realise how little our own generation spends on developing their minds, compared to the vast time and money they spend developing their bodies. Harris tried both, but the time he spent learning European languages and mastering French and German literature, and deepening his Shakespeare scholarship, puts my own generation to shame.

Or perhaps it just puts me to shame...

By coincidence yesterday, there was an item on BBC Radio 4 about education and the mismatch between the effort put into physical education compared to what you might call mental education, or at least mental health.

This is the emerging debate in education policy these days, and it is hampered because it isn't clear what works - certainly David Cameron's Blairite backing for parenting classes are not the holy grail we are looking for. The question is, if people don't want to develop their own potential, whether anything really ought to be done about it.

The answer seems to be yes, but punishing them with parenting classes seems paradoxcially like treating them too like children.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

I found myself reading it when I was researching my new book Scandal , about the strange story of why homosexuality was criminalised in 1885, and Harris knew many of the people involved. It is bizarre and hard to put down (and not really because of the pornography, I assure you).

The trouble is that Harris is widely believed to have been a liar, and his first biographer chose the sub-title 'The biography of a scoundrel'. It doesn't help that he had extraordinary powers of recall, which means - for example - that most of the copious poetry he quotes in his autobiography are clearly taken from memory and therefore not completely accurate.

This is a pity because Harris really did know everybody in the 1880s and 1890s in London and beyond and what he remembers is worth remembering. The pornography meant that unexpurgated editions were banned until 1962.

By the fourth volume you begin to feel his concentration is flagging, only to have what is an absolutely gripping account of his investigation into the abortive Jameson Raid in 1895, which led to the Boer War and arguably the rift with Germany.

But I have learned something from Harris and it followed from his own conviction that he was too short to be a great athlete. He decided he had to develop in himself the physical and mental control he needed to succeed. These are detailed at great length. Extraordinary self-confidence clearly helped.

But it made me realise how little our own generation spends on developing their minds, compared to the vast time and money they spend developing their bodies. Harris tried both, but the time he spent learning European languages and mastering French and German literature, and deepening his Shakespeare scholarship, puts my own generation to shame.

Or perhaps it just puts me to shame...

By coincidence yesterday, there was an item on BBC Radio 4 about education and the mismatch between the effort put into physical education compared to what you might call mental education, or at least mental health.

This is the emerging debate in education policy these days, and it is hampered because it isn't clear what works - certainly David Cameron's Blairite backing for parenting classes are not the holy grail we are looking for. The question is, if people don't want to develop their own potential, whether anything really ought to be done about it.

The answer seems to be yes, but punishing them with parenting classes seems paradoxcially like treating them too like children.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on January 12, 2016 03:32

January 11, 2016

Could Labour and Conservative unravel simultaneously?

I must admit I'm feeling confused about UK politics right now. We have a slow-motion unravelling of the Labour Party going on, as the old guard defend their right to insult their leadership - rather a peculiar idea, though for a Lib Dem of course it is absolutely de rigueur. Yet at the same time, on the other side of the Westminster divide, a similar process seems to be under way, even if it isn't quite so bitter.

The decision by David Cameron to allow his ministers to speak against government policy during the Euro-referendum is really remarkably like what is happening in the Labour Party. For the time being, the break up of the Conservative Party seems more controlled, but I suspect that - given that Ins and Outs are pretty equally matched - these divisions will become increasingly bitter.

So what conclusion should we draw from this extraordinary parallel?

First, I reckon that the reasons for the bitterness is also remarkably similar. The Labour rebels believe their new leadership is destroying the party. The Tory mainstream believes the same about their rebels: if they were to succeed in wrenching the nation out of the European Union, they believe it would undermine the economy. Those are life-and-death struggles, or the political equivalent.

Second, the unravelling of one side may make it safe for the other side to unravel at the same time. It might be possible that both government and opposition parties may in fact divide simultaneously.

Third, this might provide an opportunity for the Lib Dems, but only on two conditions. They have to demonstrate their own revived electorability - perhaps in Rochdale (strange to have a Sunday without new revelations about Rochdale's MP). Also they need to set out a genuine alternative, and believable, plan for national prosperity.

This is something that Tim Farron has been moving towards. The trouble is that nobody is listening right now. That may not be entirely a disadvantage - the time has come, not to hibernate, but to think and involve as broad a number of people in thinking as possible.

In fact, this is what I would do. Form a major inquiry, chaired by a prominent international economist, to set out the future radical direction for a global economy that works: one that provides for a civilised life for everyone that doesn't require increasingly frenetic and global speculation.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

The decision by David Cameron to allow his ministers to speak against government policy during the Euro-referendum is really remarkably like what is happening in the Labour Party. For the time being, the break up of the Conservative Party seems more controlled, but I suspect that - given that Ins and Outs are pretty equally matched - these divisions will become increasingly bitter.

So what conclusion should we draw from this extraordinary parallel?

First, I reckon that the reasons for the bitterness is also remarkably similar. The Labour rebels believe their new leadership is destroying the party. The Tory mainstream believes the same about their rebels: if they were to succeed in wrenching the nation out of the European Union, they believe it would undermine the economy. Those are life-and-death struggles, or the political equivalent.

Second, the unravelling of one side may make it safe for the other side to unravel at the same time. It might be possible that both government and opposition parties may in fact divide simultaneously.

Third, this might provide an opportunity for the Lib Dems, but only on two conditions. They have to demonstrate their own revived electorability - perhaps in Rochdale (strange to have a Sunday without new revelations about Rochdale's MP). Also they need to set out a genuine alternative, and believable, plan for national prosperity.

This is something that Tim Farron has been moving towards. The trouble is that nobody is listening right now. That may not be entirely a disadvantage - the time has come, not to hibernate, but to think and involve as broad a number of people in thinking as possible.

In fact, this is what I would do. Form a major inquiry, chaired by a prominent international economist, to set out the future radical direction for a global economy that works: one that provides for a civilised life for everyone that doesn't require increasingly frenetic and global speculation.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on January 11, 2016 07:55

January 4, 2016

Three political predictions for 2016

The job description of a blogger is that they predict - especially political bloggers. And especially for their

The job description of a blogger is that they predict - especially political bloggers. And especially for their first post of the year.

I had rather a good record in 2014, including calling the close result of the Scottish referendum, and felt rather proud of that. So it was with a heavy heart that I looked back to my first post of last year to see that I had confidently predicted that the Lib Dems would win 39 seats.

In short, the trick is not to extrapolate trends. The knack has to be to see beyond the trends. My only successful prediction of a year ago was that the Ukip challenge wouldn't survive the general election, and that was in the face of the apparent trends of the time. So I didn't fail completely.

The 39 seat guess seems peculiar - especially as I have now forgotten how I worked it out - but it is a measure of how unexpected the general election results would turn out to be. They still hurt, and I was just a bystander.

So I hardly dare predict anything this year, only I can't prevent myself predicting that the EU referendum will look a bit like the Scottish one - rising panic on both sides and a result that is too close to resolve the issue.

That's prediction 1. Prediction 2 is the strange rebirth of the green movement - and built on the fears people have about fracking and nuclear energy, not for themselves, but for their children's health. If I was an elected Lib Dem, which heaven knows I'm unlikely to be this year, I would be quietly positioning my party to meet this challenge.

Prediction 3. Well, there have to be three. I'd like too predict that my new venture, The Real Press, will be a swinging success, but actually I have no idea (though see my first book Scandal , available now, and about how homosexuality came to be made illegal so unexpectedly in the summer of 1885).

Perhaps it is that Corbyn will still be leader of whatever is left of the Labour Party in a year's time. One of the most peculiar feature of UK politics is actually how very little changes. All sides continue with staggering predictability.

Which is why I thoroughly commend Miranda Green's article in the Guardian on Saturday, where she singles out unpredictability as the single most important factor that the parties of the Left need to generate if they are going to make any progress.

She is absolutely right. And in the unlikely event that they manage to generate it, it will at least make the job of us political bloggers a little more difficult at New Year.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on January 04, 2016 02:08

December 21, 2015

Could Carswell actually be a Liberal?

First of all, who do you think wrote this?

"So long as there is a correlation between how people vote locally, the taxes they pay locally and the local services they get, leave it to them to decide. Give local government control over tax and spending decisions, and local democracy will shape itself. Localise the money - and let everything else follow the money. Once you have genuine local democracy, you won't need to have central government trying to define the shape and structure of it...Perhaps the real lesson in all this is that we should not leave it to the Whitehall establishment to make localism happen."

Ashdown? Farron? Stunell? Gladstone (no, I'm being silly). But it sounds, well, Liberal, doesn’t it – that radical critique of modern state institutions, and the extraordinary way in which the establishment clings to power over potholes and every other detail of local life.

The author might therefore be a surprise to the uninitiated. It is the single UKIP MP Douglas Carswell, currently wrestling with his conscience under the leadership of Jeremy Clarkson.

Oops, sorry, for some reason my subconscious mind has begun to interchange Farage and Clarkson. Why should this be? Is it that bone-headed jollity, that defensive, self-regarding humour, that English prop-up-the-bar bonhomie? I don't know.

You can see why Carswell is struggling. Farage is clever and articulate but he appeals to a particular ultra-conservative, peculiarly angry, type which is not by any means everyone. You can see the why Carswell is thinking when he criticises his own leadership. With Farage/Clarkson, UKIP is stuck. They might attract a reasonable following, but they will never sweep the nation.

I've been reading Carswell's blog and, although I only half agree with him on many issues, it seems to me - and this will no doubt horrify him - that he thinks like a Liberal.

He is beholden to no-one. He is an ardent localist. He believes that many of the institutions of state are broken and corrupt. He is a critic of the banks, but also of modern banking and the way they are needed to create the money supply.

He is not just more sophisticated than Farage/Clarkson. He can see that the critique of institutions is absolutely central to the future of politics, public institutions which hold ordinary people in thrall and private institutions which do the same - and rake off money via PFI contracts at the same time.

So here is my suggestion. Come and talk to some genuine Liberals - among whom I arrogantly include myself - and see it it might be possible for you one day to find a more congenial home in the Lib Dems (I'm talking to Carswell here...)

Of course, there is an elephant in the room. Carswell's critique of institutions makes him a ferocious critic of the European Union. No sane Liberal could be otherwise, but that doesn't mean that it is necessarily right to cast ourselves adrift from the handful of international institutions capable of bringing nations together. We might have to agree to disagree.

But there are certainly Lib Dems who will be voting to leave next year. Not many, and not me - but don't let us be uncritical of the undemocratic reality of the monster at the same time, and also the failure of so many institutions to do what they say on the tin. In fact, it would help to strengthen our own critique - which does tend to get blunted by those who cling to the purpose of the institutions without seeing the reality face to face.

Do I have my tongue in my cheek by suggesting a Dialogue with Douglas? Not really. I think it could benefit us both.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

"So long as there is a correlation between how people vote locally, the taxes they pay locally and the local services they get, leave it to them to decide. Give local government control over tax and spending decisions, and local democracy will shape itself. Localise the money - and let everything else follow the money. Once you have genuine local democracy, you won't need to have central government trying to define the shape and structure of it...Perhaps the real lesson in all this is that we should not leave it to the Whitehall establishment to make localism happen."

Ashdown? Farron? Stunell? Gladstone (no, I'm being silly). But it sounds, well, Liberal, doesn’t it – that radical critique of modern state institutions, and the extraordinary way in which the establishment clings to power over potholes and every other detail of local life.

The author might therefore be a surprise to the uninitiated. It is the single UKIP MP Douglas Carswell, currently wrestling with his conscience under the leadership of Jeremy Clarkson.

Oops, sorry, for some reason my subconscious mind has begun to interchange Farage and Clarkson. Why should this be? Is it that bone-headed jollity, that defensive, self-regarding humour, that English prop-up-the-bar bonhomie? I don't know.

You can see why Carswell is struggling. Farage is clever and articulate but he appeals to a particular ultra-conservative, peculiarly angry, type which is not by any means everyone. You can see the why Carswell is thinking when he criticises his own leadership. With Farage/Clarkson, UKIP is stuck. They might attract a reasonable following, but they will never sweep the nation.

I've been reading Carswell's blog and, although I only half agree with him on many issues, it seems to me - and this will no doubt horrify him - that he thinks like a Liberal.

He is beholden to no-one. He is an ardent localist. He believes that many of the institutions of state are broken and corrupt. He is a critic of the banks, but also of modern banking and the way they are needed to create the money supply.

He is not just more sophisticated than Farage/Clarkson. He can see that the critique of institutions is absolutely central to the future of politics, public institutions which hold ordinary people in thrall and private institutions which do the same - and rake off money via PFI contracts at the same time.

So here is my suggestion. Come and talk to some genuine Liberals - among whom I arrogantly include myself - and see it it might be possible for you one day to find a more congenial home in the Lib Dems (I'm talking to Carswell here...)

Of course, there is an elephant in the room. Carswell's critique of institutions makes him a ferocious critic of the European Union. No sane Liberal could be otherwise, but that doesn't mean that it is necessarily right to cast ourselves adrift from the handful of international institutions capable of bringing nations together. We might have to agree to disagree.

But there are certainly Lib Dems who will be voting to leave next year. Not many, and not me - but don't let us be uncritical of the undemocratic reality of the monster at the same time, and also the failure of so many institutions to do what they say on the tin. In fact, it would help to strengthen our own critique - which does tend to get blunted by those who cling to the purpose of the institutions without seeing the reality face to face.

Do I have my tongue in my cheek by suggesting a Dialogue with Douglas? Not really. I think it could benefit us both.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on December 21, 2015 03:18

December 18, 2015

How homosexuality was made a crime

Since the publication of the Boyle Review by the Cabinet Office early in January 2013, I’ve been blogging pretty intensively – inspired originally by the great Roy Lilley at nhsmanagers.net. I’ve enjoyed it enormously and felt I was playing a useful role – talking about public services from a human point of view, and economics from a Liberal point of view, in the days when Liberals preferred not to think of anything quite so grubby.

Since the publication of the Boyle Review by the Cabinet Office early in January 2013, I’ve been blogging pretty intensively – inspired originally by the great Roy Lilley at nhsmanagers.net. I’ve enjoyed it enormously and felt I was playing a useful role – talking about public services from a human point of view, and economics from a Liberal point of view, in the days when Liberals preferred not to think of anything quite so grubby.It has been pretty intense. I’ve settled down to posting about four times a week, week in week out, except for a period in the summer and at Christmas. I still have much to say but I’ve also been afraid that, in a number of ways, I am at least in danger of repeating myself.

I’m not going to stop but I have decided to calm down a little, at least for a while. At the same time, I am reserving my energy to transform The Real Blog into a new venture that tries to use the same mixture of history, politics and economics – with a human and maybe metaphysical twist – in a new way.

I’m therefore going to cut down my blog posts to weekly or bi-weekly and to concentrate for the next few months on launching The Real Press, an ebook publishing venture dedicated to the same ideas.

I’ve very much enjoyed the debate and the people I’ve met online as a result of this blog and I hope that interaction can continue. I’m already in the middle of publishing our first titles – they will be available as very low-cost ebooks and as print-on-demand titles, from various different platforms. This blog will provide some news of them, and I’m very excited about some of the people who have agreed to write for us. More on that in due course.

The first title will be formally launched early next year, but it is available on Amazon already – it will be available in other places shortly.

This is Scandal: How homosexuality became a crime , and it is a response to the growing role of gender and identity politics in the UK, realising that – despite the furore about Alan Turing and the abolition of most homosexuality laws in 1967 - nobody had really explained how the criminalisation had originally taken place, so suddenly and unexpectedly in the summer of 1885.

The answer is unexpected, and was particularly unexpected for me, as it turned out. The roots of the new law, the Labouchere amendment – pushed through the Commons at dead of night in just a few minutes – lay in Irish politics, an attempt by the nationalists to regain the moral high ground after the Phoenix Park murders. This led to the largely forgotten events, the first political sex kerfuffle, known as the Dublin Scandal of 1884.

What was unexpected for me was the role my own family played in those events, leading to the escape in disguise from Dublin of my banker great-great-grandfather in July 1884 ahead of the arrests. My family hasn’t lived in Dublin since.

I discovered how he came to live, estranged from his family and in what would now be called a gay relationship, in London’s Denmark Hill – and became a stained glass artist. But it was what happened later in 1895, when he was forced to disappear again during the Oscar Wilde trial, that was the real revelation for me: a unique moment of fear in the modern British story that has been erased from our collective history.

The book recreates that strange chapter in forgotten history. You can download it here, or buy a print version here. Other versions will follow after the book is officially launched in the New Year.

I will still be blogging in the usual way next year, but less exhaustingly (for me at least), so I will see you then. Thank you so much for reading during 2015 and have a very merry Christmas.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on December 18, 2015 04:53

December 17, 2015

Not Mr Cameron's poodle

Shortly after taking office in 1997, Tony Blair made a ridiculous gaffe in the House of Commons where he claimed that “sovereignty” remained with him.

Shortly after taking office in 1997, Tony Blair made a ridiculous gaffe in the House of Commons where he claimed that “sovereignty” remained with him.Paddy Ashdown slapped him down, reminding him that sovereignty actually lay with the people – or with people, if you don’t believe in such concepts.

This important exchange is now largely forgotten, but the question that lies behind it is suddenly important. Why does what passes for a British constitution allow prime ministers to flirt with the idea that they are monarchs, temporary kings whose writ must be obeyed? Because there is nothing in our history or constitution suggesting that this is the case.

I mention this because, in political terms, I suppose we are now seeing what you might call a cloud no bigger than man’s hand.

The Conservative end of the coalition failed to honour their manifesto promise and reform the House of Lords to make it more democratic, more legitimate and more effective.

So now, when the Lords begins to assert itself as an effective second chamber, it has no democratic legitimacy and so David Cameron announces plans to emasculate it – in effect to abolish it as a meaningful contributor to British law-making beyond a mild tweaking function.

It is a reverse of the struggle between the Liberal government and the Conservative dominated Lords that took place a century ago. In those days, it was known by Asquith as ‘Mr Balfour’s Poodle’. Now that it is nobody’s poodle, the Conservatives are moving towards abolition.

Ironic really, given that it is the rise of the Liberal block in the Lords that now most upsets the government. They say it has no democratic legitimacy, as if somehow nobody had voted Lib Dem in the general election.

But what really confuses me is why we seem unable in this country to incorporate an effective and democratic second chamber, as most civilised nations have. Why the obsession with control? Why the obsession with enforcing decisions, rather than on making good decisions? We all know the appalling mistakes made by UK governments because there is no check on them.

In fact, British government suffers because it is structured like a kind of tyrannical state, using monarchical powers to force through decisions on behalf of whoever manages to win a majority of MPs – this is nothing to do with a majority of the votes.

In short, we have no proper separation of powers. No civilised balance dedicated to making the right decisions. A sort of childish petulance and fear that ministerial whim will not somehow be obeyed, which seems to engulf both Conservative and Labour in government – and which is one reason why the coalition experiment was actually extremely successful (except of course for the Lib Dems).

But now we have the cloud no bigger than a man’s hand. I hope the Lords will vote down the legislation to remove their revising powers. Then we will have the second constitutional crisis in a century on the same issue.

Except that this one could so easily have been avoided if Blair and Cameron had done what, in different ways, they had promised to do,

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on December 17, 2015 14:23

December 15, 2015

Bigger scale children's services will fail bigger

Imagine you are in need of some human sympathy and your care is handed over to a computer, or at least to human beings under the rigid orders of a computer. How would you feel?

Because that seem to me to be the main side effect of handing over failing children's services regimes to other local authorities.

If the main story today has been the second British astronaut in space, the main story yesterday is still echoing round what passes for my mind. It is the removal of children from their mothers at birth and the failure of some children's services at local authority level.

And what happens when they fail? They are given to a more successful local authority, defined as a "high performing" one. For high-performing, read good KPIs - not necessarily the same thing at all.

There are a number of arguments in favour of this approach. It doesn't require external commissioners and it means, at least, handing over services to someone who knows what they are doing. But there are drawbacks too. and it seems to me that the argument about this is never really engaged - and yet it may be the real division within politics in the next generation. It is about scale.

Most assumptions behind the administration of public services are that we are still in the era of mass production and economies of scale, which means that services seem to be more efficiently delivered in large quantities and by big units.

But there is an emerging counter argument, from people like the system thinker John Seddon, which suggests that economies of scale are very rapidly overtaken by diseconomies of scale - and that these tend to remain invisible in someone else's budget, so the system ignores them.

I've spent this week at the round of nativity concerts at school and I'm reminded of how this works in the education system. Despite the occasional blip, our primary schools are the jewel in the crown of UK public services. They are effective, human-scale, widely co-produced by parents and extremely efficient.

The secondary schools are not always these things at all, and I've been puzzling out why, despite the rhetoric, they tend to be aloof, technocratic, somewhat intolerant and overly concerned about appearances. They stress children out in the interest of their education and they, in turn, stress each other. I'm particularly concerned about the failure of my son's school to provide enough tables at lunchtime. It may seem a little thing, but it matters.

Why this gap? Because they are too big. They need technocratic systems to control them. They need to be managed by rules and computers, rather than by a human-scale, humane, flexibility that most primary schools seem to manage. Educationalists obsess about 'maximising the teaching time' because actually the whole set up is not very conducive to learning in the first place. Learning requires relationships and the institutions are too big to manage that.

Now imagine the same shift happening in social services, and you can see why this is important. Big scale social services or children's services will be less effective, less humane, more inflexible and will deliver themselves feedback in the form of target figures and KPIs that will entirely obscure this reality.

Some years ago now, I sought out the research on scale on both sides of the Atlantic. We have known since 1964 that there are activities outside the classroom in the smaller schools than there in the bigger schools. There were more pupils involved in them in the smaller schools, between three and twenty times more in fact. Children were more tolerant of each other in small schools. There was more diversity in the teaching in small schools.

It seems pretty clear also that the smallest police forces are the most effective, catching more criminals for their population than the big ones. That is another reason why American hospitals cost more to run per patient the bigger they get. These are the costs of scale in the public sector.

There is some evidence of the costs of size in the private sector too. When the business writer Robert Waterman says that the key to business success is “building relationships with customers, suppliers and employees that are exceptionally hard for competitors to duplicate,” you know things will have to shift. Because size gets in the way of that.

There is evidence that the bigger companies get – and the more impersonal – then the less innovative they are able to be, which is why so many pharmaceutical companies are outsourcing their research to small research start-ups. In fact, this trend seems to have been going on for most of the twentieth century. Half a century ago, the General Electric finance company chairman T. K. Quinn put it like this:

“Not a single distinctively new electric home appliance has ever been created by one of the giant concerns – not the first washing machine, electric range, dryer, iron or ironer, electric lamp, refrigerator radio, toaster, fan, heating pad, razor, lawn mower, freezer, air conditioner, vacuum cleaner, dishwasher or grill. The record of the giants is one of moving in, buying out, and absorbing after the fact.”

We have known this for years, but the system still struggles with the idea. It is time the issue of scale was made centre stage, as it deserves to be. More on scale in my book The Human Element.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Because that seem to me to be the main side effect of handing over failing children's services regimes to other local authorities.

If the main story today has been the second British astronaut in space, the main story yesterday is still echoing round what passes for my mind. It is the removal of children from their mothers at birth and the failure of some children's services at local authority level.

And what happens when they fail? They are given to a more successful local authority, defined as a "high performing" one. For high-performing, read good KPIs - not necessarily the same thing at all.

There are a number of arguments in favour of this approach. It doesn't require external commissioners and it means, at least, handing over services to someone who knows what they are doing. But there are drawbacks too. and it seems to me that the argument about this is never really engaged - and yet it may be the real division within politics in the next generation. It is about scale.

Most assumptions behind the administration of public services are that we are still in the era of mass production and economies of scale, which means that services seem to be more efficiently delivered in large quantities and by big units.

But there is an emerging counter argument, from people like the system thinker John Seddon, which suggests that economies of scale are very rapidly overtaken by diseconomies of scale - and that these tend to remain invisible in someone else's budget, so the system ignores them.

I've spent this week at the round of nativity concerts at school and I'm reminded of how this works in the education system. Despite the occasional blip, our primary schools are the jewel in the crown of UK public services. They are effective, human-scale, widely co-produced by parents and extremely efficient.

The secondary schools are not always these things at all, and I've been puzzling out why, despite the rhetoric, they tend to be aloof, technocratic, somewhat intolerant and overly concerned about appearances. They stress children out in the interest of their education and they, in turn, stress each other. I'm particularly concerned about the failure of my son's school to provide enough tables at lunchtime. It may seem a little thing, but it matters.

Why this gap? Because they are too big. They need technocratic systems to control them. They need to be managed by rules and computers, rather than by a human-scale, humane, flexibility that most primary schools seem to manage. Educationalists obsess about 'maximising the teaching time' because actually the whole set up is not very conducive to learning in the first place. Learning requires relationships and the institutions are too big to manage that.

Now imagine the same shift happening in social services, and you can see why this is important. Big scale social services or children's services will be less effective, less humane, more inflexible and will deliver themselves feedback in the form of target figures and KPIs that will entirely obscure this reality.

Some years ago now, I sought out the research on scale on both sides of the Atlantic. We have known since 1964 that there are activities outside the classroom in the smaller schools than there in the bigger schools. There were more pupils involved in them in the smaller schools, between three and twenty times more in fact. Children were more tolerant of each other in small schools. There was more diversity in the teaching in small schools.

It seems pretty clear also that the smallest police forces are the most effective, catching more criminals for their population than the big ones. That is another reason why American hospitals cost more to run per patient the bigger they get. These are the costs of scale in the public sector.

There is some evidence of the costs of size in the private sector too. When the business writer Robert Waterman says that the key to business success is “building relationships with customers, suppliers and employees that are exceptionally hard for competitors to duplicate,” you know things will have to shift. Because size gets in the way of that.

There is evidence that the bigger companies get – and the more impersonal – then the less innovative they are able to be, which is why so many pharmaceutical companies are outsourcing their research to small research start-ups. In fact, this trend seems to have been going on for most of the twentieth century. Half a century ago, the General Electric finance company chairman T. K. Quinn put it like this:

“Not a single distinctively new electric home appliance has ever been created by one of the giant concerns – not the first washing machine, electric range, dryer, iron or ironer, electric lamp, refrigerator radio, toaster, fan, heating pad, razor, lawn mower, freezer, air conditioner, vacuum cleaner, dishwasher or grill. The record of the giants is one of moving in, buying out, and absorbing after the fact.”

We have known this for years, but the system still struggles with the idea. It is time the issue of scale was made centre stage, as it deserves to be. More on scale in my book The Human Element.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on December 15, 2015 13:56

December 10, 2015

Stopping Le Pen and the far right

I notice there are epetitions going up trying to haul Tyson Fury over the coals for his politically incorrect statements. There are others going up demanding that we ban a complete buffoon from the country while he is standing for US president.

I notice there are epetitions going up trying to haul Tyson Fury over the coals for his politically incorrect statements. There are others going up demanding that we ban a complete buffoon from the country while he is standing for US president.Meanwhile, under our very noses, a far more serious threat is emerging. The Front Nationale won nearly a third of the votes in the French local elections and topped the poll. There is a real prospect now that France will elect the far right as their government.

But, hey, maybe we should start an online petition against the very idea? I jest, of course. The left has particularly vulnerable to fiddling while Rome burns these days - just as Labour MPs spent hundreds of hours debating foxhunting in 2003 when they should have been holding Blair to account for the looming Iraq war.

It may of course be that France is particularly vulnerable to this kind of political takeover, but the Vichy regime was a response to the trauma of capitulation - and I'm not sure that Le Pen looks much like Petain (see picture).

But what I find most frustrating is the way the political class, in this country - and probably in France as well (not sure about that) - seem so unable to respond. Very few have been brave enough even to try to face down the far right, though Nick Clegg's debates with Farage were undoubtedly a courageous attempt.

This is a bit of a mystery. I'd like to suggest a reason.

It is because of the enormous gulf between the purpose of our public institutions and their actual effect on the ground.

The political class clings to our institutions - the welfare state, the European Union, the DWP, because they know what the purpose was behind them and they revere them for that. They believe that, if they are failing, they can be reformed and they stare eagerly at the data without realising that it is largely delusory. Most target data is.

Those who are tempted by the far right see only the reality of these institutions, either because they deal with them and their pointless call centres and bullying nudge policies. Or because they are on the receiving end of what they see as their neglect (if there are negative sides to the influx of foreigners into the country, these are the people who feel it - in the neighbourhoods they knew as children).

Talk about this gulf to politicians in Westminster and most of them will stare at you blankly (or start an epetition against you).

But this isn't a hopeless prescription. It means that there is something we can do to head off the looming disaster of the far right taking control of a major European nation. We can undertake an urgent and systematic reform of our giant institutions, public and private, so that they are actually doing what they are designed to do - rather than generating outcome figures to make their political master think they are.

This is a major agenda to humanise institutions and make them effective. And to involve service users in the business of reforming and delivering services.

Only then could any national politician put their hand on their heart and say that we are, in any way, all in it together.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on December 10, 2015 06:31

December 9, 2015

We need to put creative people in charge of adult education

I spent part of a morning this week at the archive of the Camberwell School of Art (thanks so much, Camberwell) where I was researching a forthcoming book (of which more another time).

I read through the first minute book starting in 1898, when the school launched, and it was a pretty impressive document.

The opening of the school was part of the great revolution in adult education that followed the Technical Education Act of 1889, which allowed local authorities to charge a penny on the rates and to use it for training purposes.

The South London Technical Art School started in Kennington in 1879 and Goldsmith’s College in 1891. In fact, it was when Camberwell’s Vestry (the council) took over the art school and moved it to Peckham Road that the basis for launching an art school in Camberwell was in place. The money was given as a memorial to the artist Lord Leighton.

Peering into the minutes was like going back in time, learning about the difficulties of keeping naked models warm and the dim incandescent gas lights they used while they waited for electricity. The arts and crafts pioneer W. R. Lethaby was at the meetings, the lettering pioneer Edward Johnston was lecturing.

It was an exciting time, and especially as the central purpose was to intervene in the local trades and provide the training they needed. They had trouble with the plastering course, for example, until they found a trained plasterer to teach it, and then had to constantly subdivide the course to keep the numbers manageable. The house-painting course was also popular.

What I took away from the visit, apart from my research, was just how much the explosion in adult education, the means of training the working population during a period of great technological and social change, was handed over to the arts to fulfil. It was organised, and deliberately so, by creative people. That was the policy.

It was understood then, in a way that I don't think it is now, that creative people are necessary to the balance between technology and the arts. There is no point in training people to do coding if you don't teach them how to imagine solutions to problems, or how to make the interfaces look attractive enough to do their job effectively.

Unfortunately, we have handed over increasing swathes of our own technical education to people who think the future is about plugging people into online courses.

This is not a way to make the UK competitive in the future. So how come the Victorians knew that and we have forgotten it?

I read through the first minute book starting in 1898, when the school launched, and it was a pretty impressive document.

The opening of the school was part of the great revolution in adult education that followed the Technical Education Act of 1889, which allowed local authorities to charge a penny on the rates and to use it for training purposes.

The South London Technical Art School started in Kennington in 1879 and Goldsmith’s College in 1891. In fact, it was when Camberwell’s Vestry (the council) took over the art school and moved it to Peckham Road that the basis for launching an art school in Camberwell was in place. The money was given as a memorial to the artist Lord Leighton.

Peering into the minutes was like going back in time, learning about the difficulties of keeping naked models warm and the dim incandescent gas lights they used while they waited for electricity. The arts and crafts pioneer W. R. Lethaby was at the meetings, the lettering pioneer Edward Johnston was lecturing.

It was an exciting time, and especially as the central purpose was to intervene in the local trades and provide the training they needed. They had trouble with the plastering course, for example, until they found a trained plasterer to teach it, and then had to constantly subdivide the course to keep the numbers manageable. The house-painting course was also popular.

What I took away from the visit, apart from my research, was just how much the explosion in adult education, the means of training the working population during a period of great technological and social change, was handed over to the arts to fulfil. It was organised, and deliberately so, by creative people. That was the policy.

It was understood then, in a way that I don't think it is now, that creative people are necessary to the balance between technology and the arts. There is no point in training people to do coding if you don't teach them how to imagine solutions to problems, or how to make the interfaces look attractive enough to do their job effectively.

Unfortunately, we have handed over increasing swathes of our own technical education to people who think the future is about plugging people into online courses.

This is not a way to make the UK competitive in the future. So how come the Victorians knew that and we have forgotten it?

Published on December 09, 2015 15:34

David Boyle's Blog

- David Boyle's profile

- 53 followers

David Boyle isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.