David Clayton's Blog, page 8

February 20, 2017

How a Catholic Understanding of the Human Person Can Revolutionize the Economics of Health Provision (and the Beauty of Hospital Buildings)

I attended a talk on healthcare at Star of the Sea Catholic Church in San Francisco last week given by my colleague at Pontifex University, Dr Michel Accad last week. Much of the talk was devoted to consideration of the options that Catholics have for affordible healthcare.

Dr Accad spoke in detail about sharing ministries as alternatives to health insurance; and how many general practitioners are structuring their practices in a new way so that they are employed directly by the patient and act as their advocate. This is in contrast to the usual arrangement where the doctor effectively becomes an agent who sells treatments and drugs for the providers to the payer, who is not the patient, but the insurance company.

In his new model, in contrast Dr Accad is motivated to act on behalf of the patient first, and so is an advocate for him, striving for example to bring down the cost of treatments and drugs by negotiating with pharmaceutical companies. He is also able to devote much more time to their care. Furthermore, it enables him to offer treatment that is in accord with Catholic social teaching.

He opened up his talk by asking the question: who here thinks healthcare in this country is going well? No hands went up. He then described how it is possible to have healthcare options that allow for the flourishing of the patient as a human person – body, soul and spirit – and a relationship between doctor and patient that is fruitful for both patient and care provider.

In the Q & A session afterwards, it became apparent from the discussion that this was of interest not only to currently disgruntled patients but also to doctors who are frustrated that they cannot give the sort of treament they would like to give. Several spoke of this frustration under the current system.

Dr Accad is a medical doctor (qualified both as a general practitioner and as a cardiologist) who is able to take a broad view of the crucial issues involved. He is one of those rare people who is simultaneously able to analyse the details and to synthesise it all into the big picture. A committed Catholic he writes about medicine and is published in peer reviewed medical journals; he writes about the philosophy of nature and philosophical anthropology and has been published in The Thomist; and he has delivered papers on the economics of healthcare at the Mises Institute. He also has a popular blog on how these issues impact the medical profession called Alertandoriented.com.

Of course, I was interested in the details of how one might have access to affordible health care that is aligned with Catholic social teaching and imbued with genuine consideration of the patient as a person (and if you are interested in this I suggest you contact him through his blog, here). But aside from that what I found fascinating what his description of how so many of the problems associated with healthcare today, even before Obamacare, eminate from a dualistic understanding of the human person as a physical body occupied by a thinking soul; rather than as a single entity, a profound unity of body and soul. This is not a bad thing in itself, a deep understanding of how the physical function fo the body work as has lead to great strides in medicine; but it does place limitations on the scope of treatment through a neglect of the happiness of the person and his spiritual needs. If the underlying problem is spiritual, for example, while treatments might cause the physical symptoms to be alleviated, physical ailments might resurfacing in other forms.

And it runs even more deeply than that. Without a clear picture of what human person is, the idea of a health as a goal for treatment is not clearly defined either. This has lead over the last 100 years or so, to the creation of a ‘health market’ which has been engineered to serve that idea of a human being as machine – as an object to be repaired; rather than as a person who needs health in order to direct his activity towards his ultimate end, which is union with God. Consequently, the patient occupies a role in this financial model that is more akin to the car in the repair shop, in which the insurance company is the car owner and the doctor is the mechanic. While this model might work well for cars, when the doctor’s surgery becomes a glorified human ‘body shop’ the misalignment and conflict of interests and goals leads to secondary (and more) problems in health care.

As soon as the current system, under the guidance of the US government began to be introduced in the early 20th century, he told us, it caused escalating costs because there is no incentive for the key players to keep costs down on behalf of the patient. The doctor seeks to serve first the specialist treatment providers, pharmaceutical companies and insurance companies, rather focussing primarily on the restoration and maintainance of the health of the patient (however we define the word).

Those who wish to know more about the connection between the structuring of the health market and anthropology might be interested in reading (or listening) to Dr Accad’s talk on the subject given to the Mises Institute last year, which can be accessed via his blog, here: From Reacting Maching to Acting Person.

Dr Accad is currently preparing material for his first course for Pontifex University on the Philosophy of Nature and Philosophical Anthropology. He is a wondeful addition to the faculty precisely because of his ability to draw themes from one area of expertise and apply them in another. The development of this ability to think synthetically is part of what a good Catholic education ought to aim for and it is why a formation in beauty is so important as part of that education. When one apprehends the beauty of something, one is able to see not only how it’s parts are in right relation to the others (due proportion); but also how the whole is in accord with its purpose and in right relationship with all that surrounds it (integritas). In short one is able to look at the detail (analysis) and place it in the bigger picture (synthesis). This is why beauty and culture (which touches every aspect of human life, including economics and health provision) are so intimately related.

As Catholics we must strive always to take that mental step away from whatever field of study we are engaged in and ask ourselves the big question – how does this relate to man’s goal of union with God through worship of Him in the heavenly liturgy, in the next life, and the earthly liturgy in this.

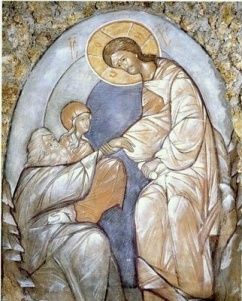

As an inspiration for this in the field of health provision I look to the Spanish saint, John of God. Here protrayed by the 17th century Spanish artist, Murillo:

St John of God, (1495 – 1550) was a Portugese born soldier who founded a hospital in Granada, Spain and whose followers later formed the Brothers Hospitallers of Saint John of God, dedicated to the care of the poor, sick, and those suffering from mental disorders.

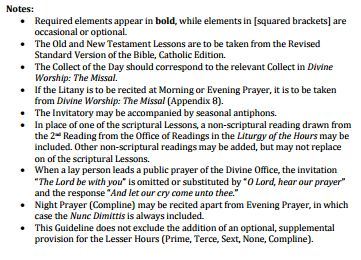

How many doctors today are taught of the need for God’s grace in their work for the benefit of both patient and doctor, I wonder? One only has to look at the design of hospital buildings past and present to see how differently the provision of care was considered. Below are photographs of the exterior and interior of the Hospital de Tavera, Toledo, Spain, built in the 16th century (which today is a museum housing many El Greco paintings):

And here is a standard National Health Service hospital building, in Darlington County Durham in England:

The standard criticism of the modern building is that it is only designed for utility, hence its depressing appearance. I would argue something different: in my opinion beauty does have a utility, which is to raise hearts and minds to God. That is when a hospital is building is beautiful, it’s beauty helps serve the spiritual needs of tall the people in the care community it houses, and for good of all concerned. Furthermore, just as the person is a profound unity of body and soul, the hospital should be a profound unity of design that aids the function of restoring the health of the all aspects of the human person. Such a hospital will be beautiful and will optimise its functionality of the provision of both spiritual care and physical care. It is no accident that the hospital, just like and educational institution built in this time, has the look of a monastery. Both institutinons have aims that cannot be separated from the supernatural end of the human person and both aim to engender a community in which all work toward this end for themselves and others.

Here’s another example, Broadmoor Hospital was purpose built as a prison for criminally insane and houses some of Britains most violent and notorious convicted criminals.

Those who are committed to its care are almost certainly going to live the rest of their natural lives behind its walls. The original building was completed in the mid-19th century. It does not have the cloisters and prayerful feel of the 16th century Spanish hospital, I suggest, but nevertheless it is a listed building. The prison/hospital is currently being redeveloped and there has been discussion as to what use the original building will be put to. Newspaper reports suggest that one suggestion is to turn it into a luxury hotel. While I am sure that it was not pleasant to be an inmate there, it seems that in some ways our Victorian forebears had greater insight about the need for the care of the souls of the most reviled members of society than modern society and how to do it.

The Darlington hospital no doubt has dedicated staff and patients receive the best that the National Health Service in the UK has to offer and the National Health Service has its problems too for similar reasons at root, although manifested in different ways (It is interesting to note that while the quality of care in many measures is not a good as that offered by the America system, satisfaction of patients is based upon anecdotal evidence, higher). Regardless, the design of the building tells us something about how the human person who is to be treated is viewed, I suggest. I would argue that it is not even the optimal design if the provision of physical care, for the physical and spiritual cannot be separated. The building of beautiful hosptials is not an extravagance, but ought be considered a necessity that will give us the most highly functional hospitals by any measure. As we can see through Dr Accad’s discussion of the provision of healthcare, care of body and soul cannot be separated, just as body and soul cannot, in reality, be separated in the person being cared for.

Neglecting the spiritual aspects of man will almost certainly affect detrimentally the care of even man-as-machine in ways that cannot always be anticipated. Let us be clear. Wrong anthropology does not suddenly invalidate what is good about modern medicine or its methods or even its method of delivery. And despite the problems, it should be said that there is still much that is good.. It simply allows to locate the source of the problems that remain with the recognition there is more to be done. Once we recognize that man is a single entity that is both physical and spiritual who is made to worship of the God in the sacred liturgy and that this is the activity that all others are ordered to in this life, then we have the greatest chance of restoring all aspects of human health (and having beautiful hospitals once again!).

January 8, 2017

New Weekly Men’s Group, Vespers and Spiritual Exercises, SF East Bay, California

The Vision for You, a group devoted to discerning personal vocation through guided prayer and reflection meets weekly at St Jerome Catholic Church, El Cerrito, Califonia, every Wednesday 7.30pm starting Wednesday 18th January.

We offer a series of workshops that explain a program of prayer and spiritual exercises rooted in the Western mystical tradition. Each week we sing Vespers according the structure of Evening Prayer of the Anglican Ordinariate. As the patron of the church of our first group, we have chosen St Jerome as a patron. This painting by Caravaggio seems so appropriate to me. St Jerome is being inspired in his work of writing the Vulgate. I like the figure of St Jerome particularly because it shows me that a man who was by no means perfect, could contribute so greatly to the work of the Church because of his faith and desire to serve God.

While the Vision for You Group is rooted in Christian spirituality, you don’t have to be Christian to benefit from this. I know this because I went through this process nearly 30 years ago when a man called David Birtwistle promised me I could have a life ‘beyond my wildest dreams’ and showed a program of prayer, meditation and contemplation that he promised would open up my life.

I was a frustrated wannabe artist who was so dispirited I hadn’t even picked up a paint brush for several months. I was attracted by the possibility of getting some structure and direction in my aimless life and thought I’d give it a go. I was a bitter atheist at the time, but put aside my prejudice sufficiently to enable me to do what was suggested (even though I was highly sceptical). This began a spiritual journey which gave me just what David had promised, and led me to being recieved into the Catholic Church.

I am still on today and a group of us who have been through this process offer this to any who wish to participate, free of charge. David died of a heart attach nearly 20 years ago now, but this method of discernment, inspired by Christian mysticism, is still working in the lives of many people. We are inspired also by Pope Benedict and his method of promoting supernatural transformation in Christ, as explained in his paper on the method of the New Evangelization.

Please do come along if you are interested. Singing experience is not necessary and we will teach everyone, no matter how poorly they think their singing ability, to chant the psalms with us. As a taster here are recordings of two the works we sing. The St Michael Prayer and Paul Jernberg’s Our Father and the Canticle of Mary. Believe me, you will be singing with us!

December 9, 2016

Breaking Bad! Why Misalettes Push People Away from Church

Especially the young!

Why has church attendance dropped off so dramatically in the last 50 years? There are a whole range of reasons, I am sure, and nearly every article in this blog is addressing the issue in one form or another, but if you ask me one of the main contributory factors is the music that is generally heard at Mass. And the degree that the music is influential, I would say that the influence of the style of music that is epitomozed by that offered by the most common pew misalettes is contributing to that decline.

I am talking about a style of music that seems to have started to develop around the late 1960s and sounds to me like a sort of fusion of American folk, Disney and Rodgers and Hammerstein musical and a hint of Victorian hymnody. Whatever you call the genre, it is responsible, I suggest for many to flee the pews.

Before anyone writes to me to say how much they like the music they hear each Sunday, or tell me how high quality the painist or band that plays and how heartily those in the congregation that do attend join in, I want to say one thing. My argument, as you will see, is not based upon the assertion that it is bad music. I do have strong opinions on that, but my personal taste has no bearing on the conclusion that I draw. My argument is that the whole philosophy that has contributed to the composition of such music is fataly flawed.

Even if we assume that the music we hear in Mass is of the highest quality within its genre, it would still have the same effect, which is to tend to drive most people away from Mass. (This is despite the fact that its proponents usually claim that it does the opposite.) Furthermore, if the standard of the musicianship is of the highest order, and the choir consisting of the best trained professional singers it would not chage my argument one iota.

The problem in my opinion lies in the whole ethos that underlies the creation of music for the missals. The goal, it seems is to connect with people by giving them music that derived from popular secular forms. The problem with this approach is that it can only connect to those people who actually listen to enjoy that style of music out of church. Today’s westerm society is so fractured that tastes vary hugely and there is no style of secular music that has universal appeal. As a result, whichever style we choose, and however well it is done, it can only every hope to appeal to a small part of the population. The rest will be driven away. So if we create music that appeals to those who were young in the late 1960s it will be detested by those who were young in the 1970s (like me) and all people who are younger.

If we go for something that is actually cutting-edge today and takes its form from current youth culture, it will drive away all the older generations and even most youth, because youth culture is itself fractured and there is no single style that all seventeen year-olds listen to. I just think of what was going on when I was seventeen – the sixth form in Birkenhead School in the 1970s (for Americans the sixth form is the upper two years of high school) was divided between punks, heavy metal fans and progressive rock fans, with a few who liked disco, funk and soul. If you’re interested I liked obscure progressive rock and jazz fusion, such as Return to Forever, Frank Zappa and Be Bop Deluxe. I used to like being seen with the LP covers tucked under my arm to show people I had highly developed music taste. There was a little crowd of Christians who were trying to be cool and had their own Christian rock music (After the Fire was the group they all liked). To me they seemed to be a sad bunch who obviously ‘just didn’t have clue’ if they thought that stuff was any good. We all used to make fun of them. It wasn’t until I was 26 and met a Christian who was just as disparaging about ‘cool’ Christianity (although less rude about them personally), and who didn’t even care about trying to be cool, hip and trendy that I started to take Christianity seriously. (He was more temperate in his language in his descriptions that I was, I should point out.)

I would refer you to the Tradition is for the Young articles by Gregory DiPippo on this blog to back up my case. But before get too smug, traditionalists aren’t exempt from this. Much ‘traditional’ church music has the same fault. Holy God We Praise They Name or Immaculate Mary is really just the On Eagles Wings from you great-grandmother’s day. All of these hymns – even the vast majority of non-chant hymns in hymn books that are considered fairly traditional, such as the Adoremus hymnal or the St Michael hymnal, sound off-puttingly ‘churchy’ to most people outside church in the wrong sort of way and drive more people away from church than they attract. I have heard them used to top and tail a Latin Mass in the past. I for one can’t bear any of these hymns – they sound just like what I grew up with going to Methodist church. I hated them when I was eight and I hate them now. It is one of the main reasons that I chose to escape from going to church when I was given the choice at 13 years old. But even if this weren’t the case and I had grown to love traditional Methodist hymns and so now loved 19th century Catholic hymns it would be no argument for their inclusion in the liturgy. The vast majority of the rest of the population would not like them and they are not instrinsically liturgical.

I would use the same argument about music that is derived from 19th century operatic styles (so strongly criticized by Pius X) is just the same. We may feel that it is a higher form of music than that provided by Christian rock band liturgy, but it will still only appeal to very narrow group of people and will drive all others away even if was written for a Latin Mass.

If the argument about the music at Mass is raised, very often the counter argument is that we have to be ‘pastoral’. It will be said that most of those attending church like the music they are getting. There would be a revolt if we changed what is so familiar to them, so the argument runs, and so we can’t risk changing the music even if we wanted to. It is almost certainly likely to be true that the people attending like the music they are getting, Those who attend do so because they like, or at least can tolerate the music. Most of those who can’t stand the music they hear at Mass just stay away. They find the experience so excruciatingly, embarrasingly banal, that they go jogging or decide to read the Sunday papers with a cup of coffee instead. This is why, I suggest, the majority of teenagers leave the moment their parents give them permission to make their own minds up. And, for the reasons already described, it will be true even if we try to find a form of music that teenagers love – because there is no form of music that most teenagers love. It doesn’t exist.

We can go further than this and raise another argument as to why the approach of the common misalette music composers of aping popular forms will inevitable cause a decline in attendance at Mass. Suppose we did have a society in which wider culture was more homogeneous and tastes were more consistent across the generations, it would still be a flawed approach.

I understand that many African cultures, for example, are more homogeneous and less fractured than western culture. This being the case, even if the music of the Mass reproduced the popular African style perfectly it would not be the right approach. This is because, although it might well appeal to a wider proportion of the population and you might find higher attendance at Mass, it would not facilitate a deeper and active participation in the liturgy.

This is because the liturgy is the wellspring of its own culture and an authentic liturgical culture must be at the heart of any Catholic culture of faith. It is separate world that appeals to what is universally human in us and draws us to God in a way that is impossible for secular culture. The music that draws us to it and directs to the Eucharist most powerfully is that which is derived from a liturgical culture, which is exemplified, the Church tells us, most fully in the forms in existence today in gregorian chant.

Secular forms that draws us to itself but then they are so far removed from the forms of liturgical culture that even in the context of the liturgy, they are inclined to leads us back to the secular values, not on to the Eucharist. It is less likely to draw us into a genuinely deep and active participation in the worship of God. In the long term therefore any secular music, even if it draws people to Mass, will inevitably lead to more people leaving the Church than staying because the music is distracting them from what is at the heart of the Mass. As a result there is less of force that draws us into a supernatural transformation of Christ. There are fewer Christians therefore with the capacity for transmitting an authentic Christian joy to those with whom they interact in their daily lives outside the Mass and the liturgy. With this reduced power for evangelzation, we will lose our lifeblood.

This is why Cardinal Sarah said in his address at the Sacra Liturgia conference in London that even in Africa the liturgy is not the place to incorporate African culture. Rather, because the liturgy has its own culture, which is uniquely and universally Christain, it should seeps into the wider culture and transforms secular culture into something greater, that is in some way derived from and points to the liturgy while simultaneously being distinctly African.

The only hope we have for the Mass to be a true long term draw capable of touching the many who currently have no interest in attending, is to focus on making chant the dominant form. We must even be prepared to allow a few of those who are currently at Masses with misalette music and who are there for the wrong reasons to drift away or even be prepared to carry on in the face of strong complaints from these people if it is changed.

While having chant at all Masses would help, even then it is not going to be enough. We must the chant in way that is going to connect with the ordinary person and this probably means singing at a pitch that is natural for men to join in. I have been told, that men are less likely to join in if you have female cantors. This is not because of an inherent sexism, but because the female voice is a pure sound and men find it difficult to come in at a pitch an octave below what the cantor is singing because it is totally separate from what he is hearing. If there is a male cantor, the men can emulate what they hear and the women still find it relatively easy to join in because the male voice contains higher harmonics which allow for a connection with female voices. Even if men are chanting, there is a style of chant in which a thin, strained, high pitch voice is encouraged. This sounds effeminate to me and I suggest has the same problems for congregations – it is not only as difficult for most men to sing along to as a female voice, but it is also difficult also to listen to, as the hearer struggles to make a connection to a voice that cannot be emulated.

Were the approach to music correct and, dare one hope for more, our liturgies were celebrated in the way that the Church truly desires, would this then bring huge numbers back to churches? In the long run, I would say yes, but in the short run, almost certainly not. But it would bring to the church immediately those who are genuinely looking for what the chant directs their hearts to – God. In the long term this would have a knock-on effect. More people who attend Mass would be participating more deeply and become emissaries of the New Evangelization, shining with the light of Christ as they go about their daily business. This, in turn, would draw others to Christ. Because we have free will this is never going to be the whole population, but I do believe that it can be far more than we cuurently see in our churches today.

Has the throw-away misalette approach to church music had its day? Probably not yet, to judge from the support that so many bishops, priests and choir directors currently give to this style in cause of a faux pastoralism, that actually alienates most people. But because of this alienation, it does contain the seeds of its own distruction. Unless it is replaced by something else, under the influcence of brave pastors and choir directors who are prepared to take the truly pastoral approach and take into consideration the majority who aren’t at church, then we are doomed to steadily declining congregations until the generation that currently listens to this style of music grows old and disappears. Faith tells us that the parasite will die before it has killed its host. The Church will remain; and so one has to conclude that at some point the music has to change before it brings the whole edifice collapses.

December 2, 2016

Please! A Simple Version of the Anglican Ordinariate Office for Lay People

Here is a both a request and proposal for the Anglican Ordinariate, if I may be so bold.

Here is a both a request and proposal for the Anglican Ordinariate, if I may be so bold.

Can you produce a version that can be reduced to a short booklet that contains the psalter and the unchanging prayers? If in addition to that we can find a way for the changing parts to be supplied by smart phone then I think that you will have something that will really catch on. It will be simple to use and cheap.

If the Ordinariate would produce something like this, then I for one would use it and promote it tirelessly. I know of several others who would be just as enthusiastic to see such a thing. Furthermore, I am ready to create online courses at Pontifex University that teach the singing of the Office in the home, and this would be my prefered option to recommend to families and lay people.

The Customary of Our Lady of Walsingham is wonderful but complicated to use and I’m never quite sure if I am getting those parts proper to the day right – and I am reasonable adept at breviary navigation. I have spoken to a number of lay people who bought it and gave up. This would work well for religious and those especially devoted to the Office who are likely to take the time to work out what

I am a great fan of the Divine Office as given to us by the Ordinariate because I think that it creates the possibility of greater take up of the praying of the Office by lay people. It offers the chance of praying the full psalter (ie no missing cursing psalms) in English in a translation that is both poetic and accessible. I have written about this in previous articles, such as this one here: The Anglican Ordinariate Divine Office – A Wonderful Gift for Lay People and a Source of Hope for the Transformation of Western Culture. (And incidentally, if you think I was resorting to hyperbole in the title of that article, I wasn’t. I really to do believe that it has this potential.)

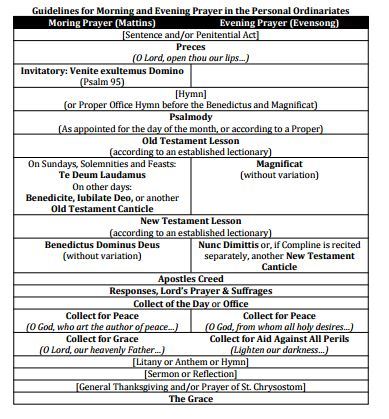

Looking at the general guide for Morning and Evening Prayer for the Personal Ordinariates (which consitutes a recitation of the full Office), and drawing on its application in the Customary, I think that I can get the psalms for the day and all that is specified in the table below from the St Dunstans Psalter. I would prefer to be using something similar that came with an endorsement from the Ordinariate.

What is missing in the St Dunstan’s Psalter are the readings and collect for the day. I can get most of this from Universalis.com via my smart phone. The morning readings are the same as those that are in the Office of Readings. What I don’t have is a readily accessible source for the Old and New Testament Lesson for Evening Prayer which is according to an established lectionary - can anyone tell me a website or other source where I might get this easily?

Although the hymn is not mandatory, if I want to use a traditional Office hymn for the day I always go to the Illuminare Publications hymnal.

The other request relates to the way that the psalms are set out. My goal is to sing everything. So please point the psalms so that the natural emphasis of speech is pointed. Then people will compose psalm tones, ideally based upon the traditional gregorian tones, that will conform to this method. If this becomes standard, then there will be the following advantages:

Every psalm tone can be applied to any psalm. That means that for people who are just learning, all they need to know is one psalm tone and they can sing the whole psalter. If they gradually learn two, three or more psalm tones then they can use those too and quickly it become interesting enough for them to be likely to keep doing it. In this system, people can learn many tones and still use this psalter – ie it allows for those with the knowledge of just one tone or those who wish to use 120 tones to have the same psalter. Also, if this pointing method becomes standard, then many people will start to compose, and as new and better tones are developed, they can easily be adopted. This allows for the possibility of chant for the vernacular as a living tradition which steadily improves and develops and really starts to connect with people.

When I sing tones to the St Dunstan’s Psalter, I ignore the pointing and the tones they give, and I have pointed the text myself according to this method and then I sing tones develop as above. This allows me to teach people to sing it very quickly and I have a regular mens group consisting mostly of people who have never sung the Office before, who are now enthusiastically singing it each Wednesday evening!

This would be in contrast to nearly every other psalter that I have seen in which even if there is some accomodation for singing, the psalm is pointed to fit a particular melody – such as the Mundelein Psalter. The disadvantage of this is that unless you know every tone already, or are musically literate enough to be able to sight read chant, you cannot sing the whole psalter. So beginners tend not to persevere. At the other end of the spectrum, those who are experienced with chant find it too dull. There are only eight or so tones, and this becomes boring very quickly. Furthermore, there is no scope for development of new tones that can be used with this psalter, as every psalm is pointed to fit a particular melody. The result is that you use their tones or nothing, and if you don’t like them you’re stuck with them.

fyi the first week of the Pontifex University free Advent meditation has a class on singing the Office complete with a description of how to point the psalms and apply our psalm tones.

November 29, 2016

Pontifex University Faculty to Lead Byzantine Liturgy on UC Berkeley Campus

Saturday, December 3rd, 5pm

Pontifex faculty member, Fr Sebastian Carnazzo, pastor of St Elias Melkite Catholic Church, Los Gatos, CA has instituted an ‘Outreach Divine Liturgy on the campus of University of California, Berkeley. Celebrating with Fr Carnazzo will be Fr Christopher Hadley. It is taking place at the Gesu Chapel at the Jesuit School of Theology, 1735 Le roay Ave., Berkeley, CA 94709.

An Outreach Divine Liturgy is the first stage to the establishment of a weekly mission. Please pray for this endeavor and if you are able to, make plans to attend. Dinner will be provided afterwards.

I shall be attending myself, singing the drone (eison) for the liturgy. We would love to see you there, especially any UC Berkeley students and professors!

Aside from teaching theology for Pontifex University on the Masters of Sacred Arts program, Fr Carnazzo is offering our Advent and Christmas meditation, which is offered free. You can sign up anytime and join in what is a wonderful to deepen your participation in this great season in sacred time.

November 26, 2016

Advent and Christmas Meditation on Art and Scripture

Pontifex University is now offering a free short course, An Advent and Christmas Seasonal Meditation as a promotion for its new Masters in Sacred Arts. It is a meditation in art and scripture for these seasons through to Epiphany It is taught by Fr Sebastian Carnazzo and myself using a method that we have developed for the scripture classes in the MSA program.

Each day, Fr Carnazzo, an experienced scripture scholar who, for example, spent several years teaching FSSP seminarians in their seminary in Nebraska, gives a short meditation on the gospel account of the nativity.

Fr Carnazzo, who is also pastor at the Melkite Church of St Elias, in Los Gatos, also has a deep knowledge of the icons of the Church. So he connects the scripture with the icons of the church. I offer additional ‘artistic sidebars’ on certain feast days during this season and on major feast days we discuss the art together. As a result, this is simultaneously a scripture class that uses beautiful art to communicate truths beyond words and so increase our grasp of the Word; and an art class that explains the scriptural roots of the icons of the Church.

Most importantly, we connect all of this to the worship of God in the sacred liturgy where, one hopes it will deepen our encounter with Him during this wonderful time in the Church year. It includes an encouragement to pray the Liturgy of the Hours in your domestic church and even offers suggestions on how families can sing the psalms as they do so.

Question: why would we be considering the Baptism of the Lord during this seasonal meditation? And who are these figures on fish in the Jordan? And the significance of the rock that Christ is standing on? Answers can be found for free…if you sign up for the course! To go to the MSA catalog page and sign up for the free course: An Advent and Christmas Seasonal Meditation

Gerrit van Honthorst, 17th century, Dutch. The Adoration of the Shepherds.

Advent and Christmas Medition on Art and Scripture

Pontifex University is now offering a free short course, An Advent and Christmas Seasonal Meditation as a promotion for its new Masters in Sacred Arts. It is a meditation in art and scripture for these seasons through to Epiphany It is taught by Fr Sebastian Carnazzo and myself using a method that we have developed for the scripture classes in the MSA program.

Each day, Fr Carnazzo, an experienced scripture scholar who, for example, spent several years teaching FSSP seminarians in their seminary in Nebraska, gives a short meditation on the gospel account of the nativity.

Fr Carnazzo, who is also pastor at the Melkite Church of St Elias, in Los Gatos, also has a deep knowledge of the icons of the Church. So he connects the scripture with the icons of the church. I offer additional ‘artistic sidebars’ on certain feast days during this season and on major feast days we discuss the art together. As a result, this is simultaneously a scripture class that uses beautiful art to communicate truths beyond words and so increase our grasp of the Word; and an art class that explains the scriptural roots of the icons of the Church.

Most importantly, we connect all of this to the worship of God in the sacred liturgy where, one hopes it will deepen our encounter with Him during this wonderful time in the Church year. It includes an encouragement to pray the Liturgy of the Hours in your domestic church and even offers suggestions on how families can sing the psalms as they do so.

Question: why would we be considering the Baptism of the Lord during this seasonal meditation? And who are these figures on fish in the Jordan? And the significance of the rock that Christ is standing on? Answers can be found for free…if you sign up for the course! To go to the MSA catalog page and sign up for the free course: An Advent and Christmas Seasonal Meditation

Gerrit van Honthorst, 17th century, Dutch. The Adoration of the Shepherds.

October 26, 2016

Way of Beauty now posting at Blog.Pontifex.University

I am taking a break from blogging regularly at the Way of Beauty for a while while I work out the future of the site.

I will be posting regularly at the Pontifex.University blog – blog.pontifex.university. Hope to see you there!

Iconostasis, Rood Screen, Communion Rail, or Shag-Pile Carpetted Step

Are we creating a holy place, or fitting out the living room?

Are we creating a holy place, or fitting out the living room?

The nature of the dividing line between sanctuary and nave in a church has been a hot topic over the years. I raise the subject today not to spill yet more ink in complaining about the removal of altar rails in churches over the last 50 years or so, although it is something I do feel strongly about. Rather, I am interested in trying to establish how, with due regard for tradition, we might encourage in the Roman Rite a renewed engagement with art in the liturgy, in the such a way that it deepens our participation, rather than distracts from it.

One thing that always strikes me when I go to an Eastern Rite Catholic Church, (recently I have been attending St Elias Melkite Church in Los Gatos, California,) is how much more naturally priest, deacon, cantor and congregation engage with the icons during the liturgy. In contrast, in the Roman Rite, even in traditional congregations, apart from perhaps the crucifix and altarpiece, the choice of art seems to be governed more by the priest’s personal devotion than liturgical considerations, and there appears to be very little engagement with it during the liturgy itself. At best, sacred art provides a decorative backdrop that helps set an appropriate mood for the worship of God with direct engagement in the liturgy itself, which is largely a hands-clasped and eyes-closed activity.

First a quick presentation of different options available to us.

According to my research, the original division in both East and West was more like today’s altar rail, with gaps or doors for processing. The typical “transenna” might have looked as this one at Sant’ Apollinarre in Ravenna, which I understand was restored in the 20th century.

Another example from the 12th century, at San Clemente in Rome, which seems to follow the early traditional style……

To read the rest of this article, go to blog.pontifex.university

October 17, 2016

How Do We Re-Establish an Artistic Tradition and Make if Relevant Today?

Pontifex University Will Teach the 13th Century English Gothic Style of the School of St Albans.

When I have had discussions about reestablishment of beautiful sacred art in the Roman Catholic Church (as opposed to in the Eastern Church) it usually comes down to picking an style from the past and then using that starting point from which a style for today emerges. So some feel that the Western Church should adopt the iconographic tradition – and then we get into discussions about which particular iconographic tradition we should go for: should it be the Greek style, the Russian style or a historic Western style such as the Romanesque? Fra Angelico’s name also often crops up as a model for today. Some feel that he has sufficient naturalism to appeal to the modern eye, and sufficient abstraction for it to seem other worldly and holy. A third is the style of English illumination in the early gothic/late Romanesque style of the Westminster Psalter, which as painted in the 13th century.

I first started looking at this latter style when I was looking for alternatives to Greek and Russian icons as teaching models for the students I was teaching to paint when I was Artist-in-Residence at Thomas More College of Liberal Arts in New Hampshire.

I noticed that when we studied images from this period the students engaged with them much more readily – they like them more than Eastern icons and seemed to understand more instinctively what they were painting. As a result some quickly developed a feel for what they could change without straying outside the style they were working in. In contrast, most who had not seen it before found the style of the Eastern icons slightly alien, and in class they had no instinctive sense of what they could change while remaining within the traditions. This meant that we had to copy rigidly for fear of introducing error. It was a bit like learning words from a language by rote without understanding the meaning of what you are saying. This is not always such a bad thing – copying with understanding is an essential part of learning art, but at some point the students must apply his understanding in new ways. This latter point seemed to be reached more quickly by these Roman Catholic students when working in the gothic style. Perhaps if I had been teaching a class of students who had grown up in the Melkite liturgy, the story might have been different!

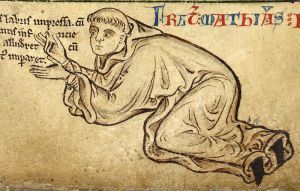

I refer to this period as the School of St Albans because the most famous artist of this period in England is a monk called Matthew Parris who was based at St Alban’s Abbey in England. There is a self portrait below with more works by him after that. The scenes below the portrait are from the life of St Thomas Becket and St Edward the Confessor:

So if we decide that this has the right style and balance of absraction and naturalism for today’s Church, how do we re-establish this as a tradition?

In answer to this, I look to the work done in restablishing the iconographic tradition in the Russian and Greek churches in the 20th century. This was done by a little group of Russian ex-patriots living in France – Vladimir Lossky, Paul Evdokimov, Leonid Ouspensky, Gregory Kroug. A Greek icon painter called Photis Kontoglou who had contact with them and took their ideas to the Greek Orthodox Church. In the middle of the 20th century these figure developed and applied a theology of the form of icons by which they established a set of principles that define the iconographic tradition. Lossky, Evdokimov, Ouspensky and to certain extent Kontoglou were theorists; Ouspensky and Kontoglou were also practitioners. Kroug was an icon painter who to my knowledge did not write extensively about icons but he, along with Ouspensky and Kontoglou painted wonderful icons. The icon below is Ouspenky’s St Seraphim.

In the mid-20th century, there were no detailed writings about art by the Church Fathers that they could draw on to define the stylistic elements in the way that was necessary to guide artists. They analysed icons that they judged to be good and holy, and developed a theology of form that seemed consistent with what they were looking at. This developed the principles that artists needed in order to create new works consistent with the tradition. The principles of this newly established iconographic tradition tell us not so much what artists did in the past, but rather what artists ought to do in the future in order to produce work that bears the mark of the holy icon.

The test of the validity of this is not historical accuracy of the principles as proposed, but rather the quality of the work produced by the artists who follow them, and the resilience of the tradition they established – can it outlast the generation that created it? We simply don’t know for certain if the formulae that Ouspensky, Lossky and Evdokimov developed correspond precisely to what Rublev, for example, would have been aiming for hundreds of years ago.

I feel that iconography has passed the test. We are now several generations of teachers and students past Ouspensky. The very best of today’s icon painters are producing icons in this style that stand alongside the great works of the past. and moreover, they are engaging with modern people in the place where they are meant to, in the context of the liturgy.

The analysis of these 20th century Russian ex-pats may very well have little credibility in the art history departments of our secular universities, where, I am guessing, it would be dismissed as purely personal speculation. But that doesn’t prevent what they proposed from being good and valid, given the end that they had in mind, namely, the creation of beautiful art that is in harmony with the liturgy.

Furthermore, while the icons that these figures painted were clearly connected to ancient icons, they also incorportated discerningly the forms of 20th century art. If you look for example at the icons of Gregory Krug, I suggest that his style has the marks of someone who has seen 20th century secular art – it is a personal observation, but I see elements of the cubism of Braques in Kroug’s style. I don’t know if this was done deliberately – quite possibly not, it might have come out naturally as Kroug made use of the images stored in his memory as he employed his imagination to create the idea of the icon he was going to paint in his mind.

So how do we do the same for the gothic School of St Albans?

I think the answer is to copy and seek to understand, so that we can articulate a set of principles that define the tradition as a guide to future artists. Here are the common features that strike me:

A strong emphasis on line-drawing. The description of form is not through modelling with graded colour and tone, but rather through simple flowing lines.

The figures themselves are well observed and naturalistic, though still retaining a symbolic quality. The degree of naturalism is higher than most icongraphic styls.

However the relationships between them are not defined by a natural perspective. They live, so to speak, in the middle distance and in the plane of the painting in the same way that iconographic figures do. This is something that artists can control quite easily once they understand how to do it.

Simple colouration – often with light washes and with the ground/foundation visible in parts.

The inclusion of geometric patterns, especially in the borders.

I would use egg tempera, mosaic or fresco as media as they are suited to the ‘flatness’ of this style. In the learning process the most convenient medium to use is egg tempera. It is cheap and clean and can be used in the sort of small space – on the kitchen table – that most people are likely to have available to them. I would work on high quality paper as readily as gessoed panels.

A large part of what will characterize the the new style will the drawing. The artists who excel at this will be expert draughtsmen who understand how line can describe form even when there is not tonal gradation in a drawing. I anticipate that a 21st century neo-gothic style would emerge naturally – the artist would naturally and unthinkingly be fusing the elements of his own artistic likes and dislikes, but as the main object of study participating also in the essential elements of the original gothic style. As result I would expect the 20th century School of St Albans to be similar to, but distinct from the 13th century gothic, and distinct also from the Victorian neo-gothic style.

At each stage as an artist, if I was taking on this style as my own, I would be asking myself (as directed by Pius XII in Mediator dei) what the original artist was trying to do, and should I do precisely what he did, or does the need of the Church today differ in a way that requires some modification? For example, I would think about the style of dress for the figures in each case – chainmail for a soldier is fine for a scene from the life of Thomas Becket, or even for a figure that symbolises to us today the idea of chivalry; but probably not for the soldiers present at the Passion. The iconographic tradition could help me in this respect. However accurate they really are historically, the style of dress used in iconography is carefully worked out to establish the idea in the the modern worshipper who looks at them that the figures portrayed are in a different time and place but is familiar to us in such as way that it reinforces what we know.

As regards the development of a theology of form, although these English illuminations come from the gothic period historically, I do not see anything in these works that contravenes the iconographic prototype of the Romanesque. They are really a more naturalized style of Romanesque art and the Romanesque conforms to the iconographic prototype. Therefore, I think that we could adopt the essential principles of iconography, as developed by these mid 20th century pioneers, but apply them in a particularly Roman Rite way.

Alternatively, some may wish to push the envelope slightly and move into a genuine gothic style (for example allowing figures in profile). I have discussed this at some length these distinction in my book, the Way of Beauty.

If you want to see examples of art in this style, go to Google Images and look for examples from the following books: Queen Mary Apocalypse, English Apocalypse, Westminster Psalter, Winchester Psalter, Douce Apocalypse, and the Psalter of Henry of Bloise.

So that’s it – I encourage you to go ahead and be radical traditionalist in the authentic spirit of the Second Vatican Council. This is precisely what Caravaggio was in his day, following the Council of Trent when he formed the baroque style that did so much for the Catholic counter-Reformation. We need artists who are post-Vat-II tradicals who can do something similar today.

If you feel you need some help in getting going, as part of our painting program, I plan to create and introductory online painting course for Pontifex University that will be available in the Spring. In it I will set out these principles and demonstrate how to make a start in egg tempera.

David Clayton's Blog

- David Clayton's profile

- 4 followers