David Clayton's Blog, page 30

July 23, 2014

The Baroque Landscape

After the 17th century, the sacred art of the academies, the baroque, declined. Landscape however, is an aspect of baroque art that not only did not decline, but actually developed in a way that was true to the original principles right through to the end of the 19th century. I will outline the basic form of landscape that established in the 17th century.

After the 17th century, the sacred art of the academies, the baroque, declined. Landscape however, is an aspect of baroque art that not only did not decline, but actually developed in a way that was true to the original principles right through to the end of the 19th century. I will outline the basic form of landscape that established in the 17th century.

The form of the baroque landscape is based upon an assumption that mankind is the greatest of God’s creatures and has a uniquely privileged position within it. The rest of creation is made by God, so that we might know him through it. Creation’s beauty calls us to itself and then beyond, to the Creator. Man is made to apprehend the beauty of creation.

To illustrate, I quote from a section of Psalm 148: ‘Praise the Lord from the earth, sea creatures and all oceans, fire and hail, snow and mist, stormy winds that obey his word; all mountains and hills, all fruit trees and cedars…’

None of these aspects of God’s creation is capable of responding to call of the psalm literally. The ‘praise’ is not theirs, but ours. Their beauty inspires and directs our praise. This is one purpose for it. The natural world is not just a collection of atoms conforming to the laws of physics and chemistry. All that it does, through grace, is in conformity to its divine purpose. Having said that, we live in a fallen world. Creation is beautiful yet, amazingly, because of the Fall, it is not as beautiful as it ought to be.

None of these aspects of God’s creation is capable of responding to call of the psalm literally. The ‘praise’ is not theirs, but ours. Their beauty inspires and directs our praise. This is one purpose for it. The natural world is not just a collection of atoms conforming to the laws of physics and chemistry. All that it does, through grace, is in conformity to its divine purpose. Having said that, we live in a fallen world. Creation is beautiful yet, amazingly, because of the Fall, it is not as beautiful as it ought to be.

When man interacts with creation (when farming or gardening, for example) he should remember this part its divine purpose and so his work with it should be beautiful too, serving to restore it more fully to fulfillment of what it was meant to be. This is why farmland is profoundly natural and when we farm well (as with anything done well) the result is beautiful.

Once this is accepted then the Christian artist who is painting the landscape should seek to reveal all these truths about Creation. As with all art this is done by consideration of both the content and the form.

The baroque landscape artist, just as I described in my piece about still lives – here – paints in such as way that it gives us information in the way that we naturally look to receive it. As the eye roves around any scene, we spend more time on those aspects which are of greater interest. Our interest reflects the natural hierarchy of being. So we are more interested in farmland than untouched areas, in animal rather than plant life, and more interested in man than a animals. The composition of the painting ought to reflect this. Even if a person is apparently a minor element in a rural scene, the artist should be aware that it is a detail that will catch the eye of the observer.

The form reflects this too. The artist varies the focus and the intensity of colour. (Again for more detail on this see the previously mentioned article.) Those areas that give the greatest amount of visual information are in sharpest focus and have the greatest colour and these are made the primary foci of the painting. The areas of least interest are rendered in monochrome and out of focus. The beauty of the painting depends upon a harmonious arrangement of these principle foci of interest (usually no more than three or four).

The form reflects this too. The artist varies the focus and the intensity of colour. (Again for more detail on this see the previously mentioned article.) Those areas that give the greatest amount of visual information are in sharpest focus and have the greatest colour and these are made the primary foci of the painting. The areas of least interest are rendered in monochrome and out of focus. The beauty of the painting depends upon a harmonious arrangement of these principle foci of interest (usually no more than three or four).

This is never easy but it can be easier in some situations than others. Consider the painting of Susanna Fourment by Rubens, left. This is set in a landscape, but because it is really just a backdrop of what is intended to be a portrait, he has it in a loose focus, largely tonal description.

The baroque developed firstly as a form of sacred art, with a focus on the human person and quickly mastered how to apply these principles to that subject. The greatest focus is in the area of the face and especially the eyes of the individual. (See this article on portraiture for more detail.)

When faced with a beautiful view in all its complexity – beyond anything a man is capable of reproducing exactly – the artist is forced to summarise. He will select those areas of greater interest and supply more detail and colour in these; visually summarise to a greater degree those areas of secondary interest.

The big problem is the one that is there for all Christian art – the balance of the particular and the general. While clouds in the sky, for example, can be represented as large forms, the problem is particularly acute with the representation of foliage. Trees, shrubs, grassland have to be represented as a collection of the particular: we are aware that a tree, for example, has many individual leaves and this must be indicated; and the general form: a tree forms a massed, cloud-like shape that must be seen as such as well.

The big problem is the one that is there for all Christian art – the balance of the particular and the general. While clouds in the sky, for example, can be represented as large forms, the problem is particularly acute with the representation of foliage. Trees, shrubs, grassland have to be represented as a collection of the particular: we are aware that a tree, for example, has many individual leaves and this must be indicated; and the general form: a tree forms a massed, cloud-like shape that must be seen as such as well.

The Dutch artists, who were not Catholic and so had less of a focus on sacred art, applied these principles to landscape with greater energy. Although I love the Dutch landscapes of this period, my personal feeling is that even they never mastered these problems in every respect with regard to foliage. If we look at the landscape by Ruisdael of Bentheim castle, above right, the trees are too feathery. There is too much focus on the particular and not enough of the general. Future articles will describe how later artists overcame this problem.

Seascapes pose a different problem, somewhat easier to overcome. The sea and clouds in the sky are more easily seen as large forms (though still requiring great skill to portray successfully if one wishes to conform to the baroque ideals). If we place a boats can be the foci, even in the distance, and then the sky and the sea can be made secondary to the composition and toned down and put evenly out of focus.

Seascapes pose a different problem, somewhat easier to overcome. The sea and clouds in the sky are more easily seen as large forms (though still requiring great skill to portray successfully if one wishes to conform to the baroque ideals). If we place a boats can be the foci, even in the distance, and then the sky and the sea can be made secondary to the composition and toned down and put evenly out of focus.

The great Dutch painter Aelbert Cuyp seemed to get around the problems by avoiding trees. He painted wonderful seascapes (see example above left) His pastoral scenes tend to be fields, or even cows standing the water! Nevertheless looking at his painting below, we see the classic baroque variation in focus and colour with even the grass pale brown except in the focal points.

The other problem relates to the variation in colour. As I mentioned, those areas of least interest are rendered tonally. The baroque tradition, with its emphasis coming from the language of light and dark in sacred art, tended to render the tonal areas in sepia, changing to blue for distant areas. The reliance on sepia works well for portraits, but landscapes with large tonal impressions sepia always give the impression of being deep shadow. It makes it difficult to paint a bright sunny day. All these paintings appear to me as though the shadows are in deep shaded woodland. Later artist began to vary the base colour of these tonal areas to blue-greys and green-greys rather than sepia. We will see in later articles how later artists, such as Corot, overcame this. It took some time for them to do so. Looking, below, at the landscape (and portrait) of a later British artist, Thomas Gainsborough, who although working in the 18th century nevertheless continued for the most part to paint in the classic baroque form, we still see this deep sepia shadow and feathery portrayal of tree foliage.

Other paintings shown are top, windmill and seascape by van Ruisdael; and second from top, Landscape with Rainbow by Rubens

July 18, 2014

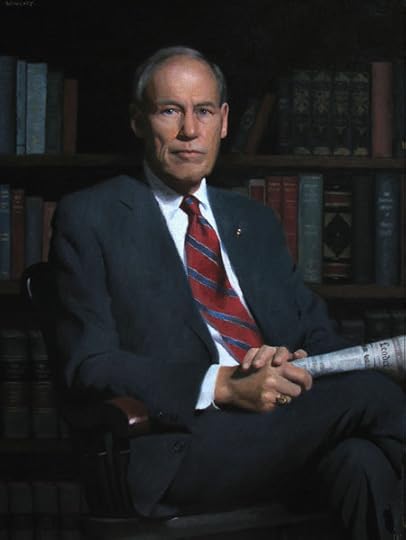

Some More about Henry Wingate, his work and the traditional style he paints in

Continuing in the tradition of the Boston School of portraitists, and the baroque.

Continuing in the tradition of the Boston School of portraitists, and the baroque.

Following on from the last post, I thought that readers might be interested to see some more work of artist Henry Wingate, and to know more about the academic method that he uses to such great effect. I like his portraits especially and he is one of relatively few artists around today who is making a real contribution to a re-establishment of traditional principles by teaching as well as painting (motivated by a desire to serve the Church).

Based in rural Virginia, Wingate studied with Paul Ingbretson in New England and with Charles Cecil, in Florence, Italy. Both Ingbretson and Cecil studied under R H Ives Gammell, the teacher, writer, and painter who perhaps more than anyone else kept the traditional atelier method of painting instruction alive.

The academic method was first developed in Renaissance Italy and was the basis of transmission of the baroque style (described by Pope Benedict XVI as one of three authentically Catholic liturgical artistic traditions, along with the gothic and the iconographic). The method is named after the art academies of the seventeenth century. The most famous early Academy was opened by the Carracci brothers, Annibali, Agostino, and Ludivico, in Bologna in 1600. Their method became the standard for art education and nearly every great Western artist for the next 300 years received, in essence, an academic training.

Under the influence of the Impressionists the method almost died out. They consciously broke with tradition and refused to pass it on to their pupils. This is strange given that all the well known Impressionists were themselves academically trained, used the skills they learned in their art and in fact could not have produced the paintings they did without it. By 1900 the grand academies of Europe had closed. The fact that it survives at all is largely the legacy of the Boston group of figurative artists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, most prominent among them John Singer Sargent (who was trained in Paris, but knew them and mixed with them). Other names are Joseph de Camp, Edmund Tarbell and Emil Grundmann. The US was slower to adopt the destructive ideas of Europe and the traditional schools survived there a little longer. Ives Gammell received his training at Boston Museum of Fine Arts in the years just before the First World War. The most well know ateliers that exist today in the US and Italy, were opened by artists who trained under Gammell in the 1970s (when he was in his 80s). Most of people painting and teaching in this style today, that I know of, come out of this line.

Under the influence of the Impressionists the method almost died out. They consciously broke with tradition and refused to pass it on to their pupils. This is strange given that all the well known Impressionists were themselves academically trained, used the skills they learned in their art and in fact could not have produced the paintings they did without it. By 1900 the grand academies of Europe had closed. The fact that it survives at all is largely the legacy of the Boston group of figurative artists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, most prominent among them John Singer Sargent (who was trained in Paris, but knew them and mixed with them). Other names are Joseph de Camp, Edmund Tarbell and Emil Grundmann. The US was slower to adopt the destructive ideas of Europe and the traditional schools survived there a little longer. Ives Gammell received his training at Boston Museum of Fine Arts in the years just before the First World War. The most well know ateliers that exist today in the US and Italy, were opened by artists who trained under Gammell in the 1970s (when he was in his 80s). Most of people painting and teaching in this style today, that I know of, come out of this line.

The ateliers of the 19th century had become detached from their Christian ethos and the sacred art of the period was inferior to that of the period 200 years before. However, portraiture, and especially that of the Sargent and the Boston School retained the principles of the balance of sharpness and focus, the variation in colour intensity and the contrast in light and dark that characterized the baroque. Today, even portraiture has declined (Wingate and his ilk being exceptions to this) because very often it is based upon photographic images rather than observation from nature. Photographs reflect the distortion of the lens of the camera, which is different from that of the eye; they have too many sharp edges and everywhere is both highly detailed and highly coloured. Consider, for example, how Wingate has handled the drapery in the portrait at the top, left. He has not supplied a fully detailed rendering, yet there is not a sense of a lack of detail because when we look at the figure, which is what Wingate wants us to look at, the detail supplied is sufficient for our peripheral vision.

The ateliers of the 19th century had become detached from their Christian ethos and the sacred art of the period was inferior to that of the period 200 years before. However, portraiture, and especially that of the Sargent and the Boston School retained the principles of the balance of sharpness and focus, the variation in colour intensity and the contrast in light and dark that characterized the baroque. Today, even portraiture has declined (Wingate and his ilk being exceptions to this) because very often it is based upon photographic images rather than observation from nature. Photographs reflect the distortion of the lens of the camera, which is different from that of the eye; they have too many sharp edges and everywhere is both highly detailed and highly coloured. Consider, for example, how Wingate has handled the drapery in the portrait at the top, left. He has not supplied a fully detailed rendering, yet there is not a sense of a lack of detail because when we look at the figure, which is what Wingate wants us to look at, the detail supplied is sufficient for our peripheral vision.

If you go somewhere where you can see a series of portraits painted over long period (perhaps those of the principals hanging in the dining hall of a long-established school or college – I recently went to a dinner at the Roxbury Latin School in Boston – founded in the 17th century), you can see this difference between the traditional and the modern portraits very easily.

those of the principals hanging in the dining hall of a long-established school or college – I recently went to a dinner at the Roxbury Latin School in Boston – founded in the 17th century), you can see this difference between the traditional and the modern portraits very easily.

I am not against photographic portraits by the way, far from it. The point is that it is a different medium to painting, to which we respond differently. These Christian considerations can be communicated through photography, in my opinion, but they have to be done differently. (And if there are any photographers out there, I think that relating the art of photography to the Christian tradition of visual imagery is an area that has not yet been properly developed.) The point here is that paintings made from photographs rarely work unless the artist is conscious of these stylistic considerations and has the skill and experience to adapt what the photographic information.

The retention of these principles in 19th-century portrait painting was not due to a Christian motivation, to my knowledge. If a portrait painter is to make a living then he cannot indulge in the free expression that one might see in other forms. The portrait painter, Christian or not, must seek to balance two things. First, he must produce a painting that is attractive to those who are going to see it, usually the individual and those who know him or her. The usual approach to this is to bring out the best human characteristics of the person. He is ennobling - idealizing – the individual. However, he cannot take this too far and go beyond the bounds of truth. He must also capture the likeness of the individual otherwise it will not be recognized as a portrait. My teacher in Florence, Charles Cecil, taught us not to be bound by an absolute standard of visual accuracy, but to modify what we saw, slightly. We were told to stray ‘towards virtue rather vice’: strengthen the chin slightly, for example. This approach is consistent with the Christian artist’s portrayal of a person, which is as much about revealing what a person can be, as what he is. The idea that the crucial aspect by which the artist reveals the person is by capturing the likeness goes back to St Theodore the Studite, the Church Father whose theology settled the iconoclastic controversy in the 9th century.

For the work of Henry Wingate, see www.henrywingate.com.

July 15, 2014

New Large-Scale Commission Completed by Henry Wingate

Artist Henry Wingate has just completed a large-scale commission for St Mary’s in Piscataway in southern Maryland.

Based in rural Virginia, Wingate studied with Paul Ingbretson in New England and with Charles Cecil, in Florence, Italy. Both Ingbretson and Cecil studied under R H Ives Gammell, the teacher, writer, and painter who perhaps more than anyone else kept the traditional atelier method of painting instruction alive.

The academic method, which Wingate teaches and uses, was first developed in Renaissance Italy and was the standard for art education and nearly every great Western artist for the next 300 years. It almost died out altogether in the first part of the 20th century but is gaining ground again now.

For this commision, Wingate writes: ‘

The subject was the baptism of the Tayac, or chief, of the Piscataway Indians by the Jesuit, Father Andrew White. This took place on July 5th, 1640. It is well documented because the Jesuits were required to send a yearly report on their efforts here in the New World to their superiors in Rome, and those documents are available to read.

The church that asked me to do the painting is Saint Mary’s of Piscataway. The baptism took place in the Piscataway Indian village which was someplace near where this church stands today, possibly even on the land owned by the church. The painting is in the entrance way to the church, and above the new baptismal font. I finished the painting after about seven months of work, in time for an Easter unveiling. At the Easter Mass their were three baptisms using the new font. Two of those baptized were descendants of Piscataway Native Americans. One of the most interesting things I learned while doing this project is that most of the Piscataways, to this day, are practicing Catholics. Father Andrew White’s efforts, and those of his fellow Maryland Jesuits, were very effective.

The painting is 16 feet across and nearly 13 feet high. It is on canvas that is glued to panels. I had to cut a slot in my studio wall just to get the painting out and into a truck to get it to Maryland.

I used models from around Madison mostly. The Native Americans were a little more difficult to find. I did have two real Piscataways pose for me, the older man in the background and the young wife of the chief. The Piscataways were very helpful in lending me articles of clothing, headresses and so on.’

The photographs show the completed painting and preliminary studies.

July 7, 2014

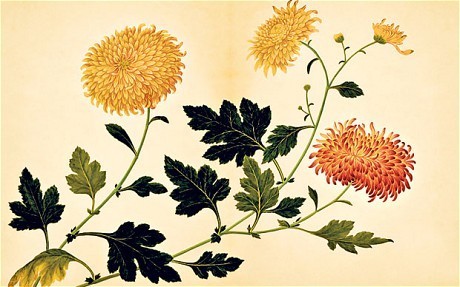

Learn Botanical Painting – Another Option for those Who Want to Learn to Draw and Paint

My friend Nancy Feeman who has written occasionally for this blog has now started her own blog. This article about botanical painting is very interested. She told me recently about her experiences of learning botanical painting and drawing at a class in Massachusetts and I was enthusiastic to see her write about it.

My friend Nancy Feeman who has written occasionally for this blog has now started her own blog. This article about botanical painting is very interested. She told me recently about her experiences of learning botanical painting and drawing at a class in Massachusetts and I was enthusiastic to see her write about it.

I was fascinated to hear of the drawing techniques taught and the lessons in observation. The discipline required and the ethos behind it, as articulated by her teacher is very traditional; what struck me is that to do such a course would be an excellent way to learn the skill of drawing and painting. Once learned this could have application in any form of art in which these skills are necessary.

Nancy’s article is here, and her blog is spiritoftruthandbeauty.com.

July 4, 2014

A Model for A Cultural Center for the New Evangelization

Going Local for Global Change.

Going Local for Global Change.

How About a Chant Cafe with Real Coffee ..and Real Chant?

There is a British comedienne who in her routine adopted an onstage persona of a lady who couldn’t get a boyfriend and was very bitter about it (although in fact as she became a TV personality beyond the comedy routines, she revealed herself as a naturally engaging and warm character who was in fact happily married with a child). Jo Brand is her name and she used to tell a joke in which she said: ‘I’m told that a way to a man’s heart is through his stomach. I know that’s nonsense - guys will take all the food you give them but it doesn’t make them love you. In fact I’ll tell you the only certain way to man’s heart…through the rib cage with a bread knife.’ Well wry humour aside, I think that in fact there is more truth to the old adage than Jo Brand would have acknowledged (on stage at least). Perhaps we can touch people’s hearts in the best way through food and drink, and in particular coffee.

There is a coffee shop in Nashua NH where I live called Bonhoeffer’s. It is the perfect place for conversation. They have designed it so that people like to sit and hang out – pleasing decor, free wifi, and different sitting arrangements, from pairs of cozy arm chairs to highbacked chairs around tables. The staff are personable and it is roomy enough that they can place clusters of chairs and sofas that are far enough apart so that you don’t feel that you are eavesdropping on your neighbors’ conversation; and close enough together that you feel part of a general buzz of conversation around you. There is not an extensive food menu but what they have is good and goes nicely with the image it conveys of coffee and relaxed conversation – pastries, a slice of quiche or crepes for example. It has successfully made itself a meeting place in the town because of this.

This is all very well and good, if not unremarkable. But, you wouldn’t know unless you recognized the face of the German protestant theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer in the cafe logo and started to ask questions, or noticed and took the time to read the display close the door as you are on your way out, that it is run by the protestant church next door, Grace Fellowship Church. Furthermore a proportion of turnover goes towards supporting locally based charities around the world – they list as examples projects in the Ukraine, Myanmar, Ethiopia, Haiti and Jamaica on their website. Talks and events linked to their faith are organised and there are pleasant well equipped meeting rooms available for hire. I include the logo and website to illustrate my points, but also in the hope that if Bonhoeffer’s see this they might push an occasional free coffee in my direction…come on guys!

Well, it was worth a try. Anyway, back to more serious things…the presentation of their mission does not even dominate the cafe website which talks more about things such as the beans they use in their coffee, prices and opening times and the food menu. The most eye-catching aspect when I was nosing around is the announcement of the new crepes menu! There is one tab that has the heading Hope and Life Kids and when you click it it takes you through to a dedicated website of that name, here , which talks about the charity work that is done.

I went into Bonhoeffer’s recently with Dr William Fahey, the President of Thomas More College, just for cup of coffee and a chat, of course, and he remarked to me as we sat down that this is the sort of the thing that protestants seem to be able to organize; and how we wished he saw more Catholics doing the same thing.

I agree. What the people behind this little cafe had done was to create a hub for the local community that has an international reach. It is at once global and personal. I would like to see exactly what they have done replicated by Catholics. But, crucially, good though it is I would add to it, and make it distinctly Catholic so that it attracts even more coffee drinkers and then can become a subtle interface with the Faith, a focus for the New Evangelization in the neighborhood.

I agree. What the people behind this little cafe had done was to create a hub for the local community that has an international reach. It is at once global and personal. I would like to see exactly what they have done replicated by Catholics. But, crucially, good though it is I would add to it, and make it distinctly Catholic so that it attracts even more coffee drinkers and then can become a subtle interface with the Faith, a focus for the New Evangelization in the neighborhood.

I don’t know how to run coffee shops, so I would be happy with a first step that copied precisely theirs – the establishment of coffee shop that competes with all others in doing what coffee shops are meant to do, sell coffee. Then I would offer through this interface talks and classes that transmit the Way of Beauty, many of which are likely to have an appeal to many more than Catholics (especially those with a ‘new-age spiritual’ bent). There are a number that come to mind that attract non-Christians and can be presented without compromising on truth – icon painting classes; or ‘Cosmic Beauty’ a course in traditional proportion in harmony based upon the observation of the cosmos; or praying with the cosmos - a chant class that teaches people to chant the psalms and explains how the traditional pattern of prayer conforms to cosmic beauty.

Another class that might engage people is a practical philosophy class that directs people towards the metaphysical and emphasizes the need of all people to lead a good life and to worship God in order to be happy and feel fulfilled. This latter part is vital for it is the practice of worship that draws people up from a lived philosophy into a lived theology and ultimately to the Faith. For it is only once experienced that people become convinced and want more. This works. When I was living in London I used to see advertisements in the Tube for a course in practical philosophy. These were offered by a group that had a modern ‘universalist’ approach to religion in which they saw each great ‘spiritual tradition’ as different cultural expressions of a single truth that were equally valid. The adverts however, did not mention religion at all but talked about the love and pursuit of universal wisdom that looked like a new agey mix of Eastern mysticism and Plato. The content of the classes, they said, was derived from the common experience of many if not all people and from it one could hope to lead a happy useful life. They had great success in attracting educated un-churched professionals not only to attend the class, but also to go in to attend more classes and ultimately to commit their lives to their recommended way of living. They were also prepared to donate generously – this is a rich organisation. Their secret was the emphasis on living the life that reason lead you to and not require, initially at least a commitment to formal religion. Most became religious in time, which ultimately lead some to convert to Christianity – although many, because of the flaws in the opening premises and the conclusion this lead to, were lead astray too. It was by meeting some of these converts that I first heard about it. There is room, I think, for a properly worked out Catholic version of this.

Another class that might engage people is a practical philosophy class that directs people towards the metaphysical and emphasizes the need of all people to lead a good life and to worship God in order to be happy and feel fulfilled. This latter part is vital for it is the practice of worship that draws people up from a lived philosophy into a lived theology and ultimately to the Faith. For it is only once experienced that people become convinced and want more. This works. When I was living in London I used to see advertisements in the Tube for a course in practical philosophy. These were offered by a group that had a modern ‘universalist’ approach to religion in which they saw each great ‘spiritual tradition’ as different cultural expressions of a single truth that were equally valid. The adverts however, did not mention religion at all but talked about the love and pursuit of universal wisdom that looked like a new agey mix of Eastern mysticism and Plato. The content of the classes, they said, was derived from the common experience of many if not all people and from it one could hope to lead a happy useful life. They had great success in attracting educated un-churched professionals not only to attend the class, but also to go in to attend more classes and ultimately to commit their lives to their recommended way of living. They were also prepared to donate generously – this is a rich organisation. Their secret was the emphasis on living the life that reason lead you to and not require, initially at least a commitment to formal religion. Most became religious in time, which ultimately lead some to convert to Christianity – although many, because of the flaws in the opening premises and the conclusion this lead to, were lead astray too. It was by meeting some of these converts that I first heard about it. There is room, I think, for a properly worked out Catholic version of this.

Along a similar line are classes that help people to discern their personal vocation, again using traditional Catholic methods. Once we discover this then we truly flourish. God made us to desire Him and to desire the means by which we find Him. While the means by which we find Him is the same in principle for each of us, we are all meant to travel a unique path that is personal to us. To the degree that we travel this path, the journey of life, as well as its end, is an experience of transformation and joy.

Along a similar line are classes that help people to discern their personal vocation, again using traditional Catholic methods. Once we discover this then we truly flourish. God made us to desire Him and to desire the means by which we find Him. While the means by which we find Him is the same in principle for each of us, we are all meant to travel a unique path that is personal to us. To the degree that we travel this path, the journey of life, as well as its end, is an experience of transformation and joy.

Drawing on people from the local Catholic parishes I would hope to start groups that meet for the singing of an Office – Vespers and or Compline or Choral Evensong and fellowship on a week night; and have talks on the prayer in the home and parish as described by the The Little Oratory. This book was intended as a manual for the spiritual life of the New Evangelization and would ideally be one that supports the transmission of practices that are best communicated by seeing, listening and doing. These weekly ‘TLO meetings’ would be the ideal foundation for learning and transmitting the practices. They would be very likely a first point of commitment for Catholics who might then be interested in getting involved in other ways. It would enable them also to go back to their families and parishes teach any others there who might be interested to learn.

Drawing on people from the local Catholic parishes I would hope to start groups that meet for the singing of an Office – Vespers and or Compline or Choral Evensong and fellowship on a week night; and have talks on the prayer in the home and parish as described by the The Little Oratory. This book was intended as a manual for the spiritual life of the New Evangelization and would ideally be one that supports the transmission of practices that are best communicated by seeing, listening and doing. These weekly ‘TLO meetings’ would be the ideal foundation for learning and transmitting the practices. They would be very likely a first point of commitment for Catholics who might then be interested in getting involved in other ways. It would enable them also to go back to their families and parishes teach any others there who might be interested to learn.

We could perhaps sell art by making it visible on the walls or have a permanent, small gallery space adjacent to the sitting area (provided it was good enough of course - better nothing at all than mediocre art!). All would available in print form online as well of course, just as talks could be made available much more widely and broadcasted out across the net if there was interest. This is how the local becomes global.

What I am doing here is taking the business model of the cafe and combining it with the business model of the Institute of Catholic Culture which is based in Arlington Diocese in Virginia. I wrote about the great work of Deacon Sabatino and his team at the ICC in Virginia in an article here called An Organisational Model for the New Evangelization – How To Make it At Once Personal and Local, and have International Recognition. His work is focussed on Catholic audiences, and is aimed predominently at forming the evangelists, rather than reaching those who have not faith (although I imagine some will come along to their talks). By having an excellent program and by taking care to ensure that his volunteers feel involved and are appreciated and part of a community (even organising special picnics for them) Deacon Sabatino has managed to get hundreds volunteering regularly.

Another group that does this just well is the Fra Angelico Institute for Sacred Arts in Rhode Island run by Deacon Paul Iacono. I have written about his great work here. The addition of a coffee shop give it a permanent base and interface with non-Catholics and even the non-churched.

I would start in a city neighborhood in an area with a high population and ideally with several Catholic parishes close by that would provide the people interested in attending and be volunteers and donors helping the non-coffee programs. It always strikes me that the Bay Area of San Francisco, especially Berkeley, is made for such a project. There is sufficiently high concentration of Catholics to make it happen, a well established cafe culture; and the population is now so far past ‘post-Christian’ that there is an powerful but undirected yearning for all things spiritual that directs them to a partial answer in meditation centers, wellness groups, spiritual growth and transformation classes, talks on reaching for your ‘higher self’ and so on. Many are admittedly hostile to Christianity, but they seek all the things that traditional, orthodox Christianity offers in its fullness although they don’t know it. Provided that they can presented with these things in such a way that it doesn’t arouse prejudice, they will respond because these things meet the deepest desire of every person.

I would start in a city neighborhood in an area with a high population and ideally with several Catholic parishes close by that would provide the people interested in attending and be volunteers and donors helping the non-coffee programs. It always strikes me that the Bay Area of San Francisco, especially Berkeley, is made for such a project. There is sufficiently high concentration of Catholics to make it happen, a well established cafe culture; and the population is now so far past ‘post-Christian’ that there is an powerful but undirected yearning for all things spiritual that directs them to a partial answer in meditation centers, wellness groups, spiritual growth and transformation classes, talks on reaching for your ‘higher self’ and so on. Many are admittedly hostile to Christianity, but they seek all the things that traditional, orthodox Christianity offers in its fullness although they don’t know it. Provided that they can presented with these things in such a way that it doesn’t arouse prejudice, they will respond because these things meet the deepest desire of every person.

Here’s the additional element that holds it all together. As well as the workshops or classes I have mentioned I would have the Liturgy of the Hours prayed in a small but beautiful chapel adjacent to and accessible from the cafe on a regular basis, ideally with the full Office sung. The idea is for people in the cafe to be aware that this is happening, but not to feel bound to go or guilty for not doing so. I thought perhaps a bell and announcement: ‘Lauds will be chanted beginning in five minutes in the chapel for any who are interested.’ Those who wish to could go to the chapel and pray, either listening or chanting with them. The prayer would not be audible in the cafe. So those who were not interested might pause momentarily and then resume their conversations.

From the people who attend the TLO meetings I would recruit a team of volunteers might volunteer to sing in one or more extra Offices during the week if they could. If you have two people together, meeting in the name of Jesus, they can sing an Office for all. The aim is to have the Office sung on the premises give good and worthy praise to God for the benefit of the customers, the neighbourhood, society and the families and groups that each participates in aside from this and for the Church.

When the point is reached that the Office is oversubscribed, we might encourage groups to pray on behalf of others also in different locations by, for example singing Vespers regularly in local hospitals or nursing homes. I describe the practice of doing this in an appendix in The Little Oratory and in a blog post here: Send Out the L-Team, Making a Sacrifice of Praise for American Veterans.

As this grows, the temptation would be to create a larger and larger organization. This would be a great error I think. The preservation of a local community as a driving force is crucial to giving this its appeal as people walk through the door. There is a limit to how big you can get and still feel like a community. Like Oxford colleges, when it gets to big, you don’t grow into a giant single institution, but limit the growth and found a new college. So each neighborhood could have its own chant cafe independently run. There might be, perhaps a central organization that offers franchises in The Way of Beauty Cafes so that the materials and knowledge needed to make it a success in your neighborhood are available to others if they want it.

I have made the point before that eating and drinking are quasi-liturgical activities by which we echo the consuming of Christ Himself in the Eucharist (it is not the other way around – the Eucharist comes first in the hierarchy). So it should be no surprise to us that food and drink offered with loving care and attention open up the possibilities of directing people to the love of God. If the layout and decor are made appropriate to that of a beautiful coffee shop and subtly and incorporating traditional ideas of harmony and proportion, and colour harmony then it will be another aspect of the wider culture that will stimulate the liturgical instincts of those who attend. (I have described how that can be done in the context of a retail outlet in an appendix of The Little Oratory.) We should bare in mind Pope Benedict’s words from Sacramentum Caritatis (71):

‘Christianity’s new worship includes and transfigures every aspect of life: “Whether you eat or drink, or whatever you do, do all to the glory of God.” (1Cor 10:13) Here the instrinsically eucharistic nature of Christian life begins to take shape. The Eucharist, since it embraces the concrete, everyday existence of the believer, makes possible, day by day, the progressive transfiguration of all those called by grace to reflect the image of the Son of God (cf Rom 8:29ff). There is nothing authentically human – our thoughts and affections, our words and deeds – that does not find in the sacrament of the Eucharist the form it needs to be lived in the full.’

So Jo Brand, we’ll put away the bread knife and offer the bread instead!

Step one seems to be…first get your coffee shop. Anyone who thinks they can help us here please get in touch and we’ll make it happen!

July 1, 2014

Just Because I Like It, It Doesn’t Mean It’s Good

If I can’t trust my taste in food, can I trust my taste in art? I like chocolate cake. I don’t know for certain, but I am guessing that there aren’t many nutritionist out there who would argue that chocolate cake is good food. So here’s the point. If the food I like isn’t necessarily good food, might it be true also for the art I like?

If I can’t trust my taste in food, can I trust my taste in art? I like chocolate cake. I don’t know for certain, but I am guessing that there aren’t many nutritionist out there who would argue that chocolate cake is good food. So here’s the point. If the food I like isn’t necessarily good food, might it be true also for the art I like?

Good art, I would maintain, communicates and reflects truth; and it is beautiful. There should never be any conflict between the good, the true and beautiful for they are all aspects of being and exist in the object being viewed, for example a painting. However sometimes it might appear as though there is a conflict. We might think something is false, yet find it beautiful for example.

Or that something is ugly but good. I have heard some people say that they like Picasso’s Guernica, see below, because its ugliness speaks of suffering. I would say contrary to this that if it is ugly, and it looks it to me, it must be bad. (I might go on and explain that this is contrary to truth because Christian art reveals suffering, but always with hope rooted in Christ, the Light of the World who overcomes the darkness. Such a painting, if successful will always be beautiful. what Geurnica lacks is Christian hope. ) In regard to the general principle, who is right? How can we account for these apparent contradictions between the good and the beautiful?

Many today would respond by asserting the subjectivity of the viewer. That is, they would say that my premise is wrong and the qualities good, true and beautiful are just a matter of personal opinion; and they are not necessarily tied to each other in the way I described. If they are right then there is nothing disordered about liking ugliness; or hating beauty; or thinking that something is both ugly and good at the same time.

I do not accept this. The answer for me lies in accepting that we have varying abilities to recognize goodness, truth and beauty. This gap between reality and our perception of it has its roots in our impurity. Since the Fall, we see these qualities only ‘through a glass darkly’ so to speak and our judgement, to varying degrees, can be disordered. This is where food comes into the discussion.

Now, more than chocolate cake, I love fluorescent-orange cheesey corn puffs. In England are they are called Cheezy Wotsits (pictured right…and don’t they look delicious!). I have an insatiable appetite for these wonderful dusted pieces of crunchy manna. The dust they are coated with is ‘cheese-flavoured’ – there’s no pretence that there is any real cheese involved (and those brands where the manufacturer claims that real cheese is one of the ingredients, are inferior in taste in my opinion).

Now, more than chocolate cake, I love fluorescent-orange cheesey corn puffs. In England are they are called Cheezy Wotsits (pictured right…and don’t they look delicious!). I have an insatiable appetite for these wonderful dusted pieces of crunchy manna. The dust they are coated with is ‘cheese-flavoured’ – there’s no pretence that there is any real cheese involved (and those brands where the manufacturer claims that real cheese is one of the ingredients, are inferior in taste in my opinion).

I could happily enjoy three meals a day consisting of nothing else and never get tired of them. But I don’t do that because I know that however much I like them they are not good food…or not if you eat them in the quantities that I want to eat them anyway. I would end up overweight and have permanently colour-stained fingers and lips.

So where does this leave us in trying to decide if a work of art is good. There are no rules of beauty by which I can decide how beautiful something is on a scale of 1-10. There is no artistic expert doing the equivalent what the nutritionist has done for the Cheesy Wotsit: a scientist with beauty meter that gives a definitive answer. For all that I might use ideals of harmony and proportion when creating art, the process of apprehending beauty after the fact is always intuitive. When I see a tree, I don’t go out and measure to see if it’s beautiful. I look at it and decide that it is. It’s just like harmony in music. The composer follows the rules of harmony, but listener just listens and decides if it is beautiful.

But the fact that it is difficult to discern, doesn’t mean that it is not an objective quality. It just means that I should try to be as discerning as I can. And here’s how I approach this problem: because I know that the good and the true and beautiful must all exist in equal measure in any particular object, I ask myself certain pointed questions to help me judge them and only if the answer is yes will I select the piece:

Is it communicating truth? This means that I look at the content and the form (see Make the Form Conform) and ask myself if what is being communicated is consistent with a Catholic worldview. If it isn’t I reject it, regardless of whether or not I like it.

The second question I ask myself is do I think it is beautiful? If I at least try to make a judgement on beauty then at least I stand a chance of getting it right. And this probably isn’t as unreliable as you might think. When I go through this process with the classes I teach I ask them if they like a piece. Very often there is a split within the class. However, when I ask the question: do you think this is beautiful? There is almost always a much higher degree of consensus. Christopher Alexander, an architect, wrote a book in which he described an experiment he carried out. He presented people with an object and then asked a range of questions and observed the degree of consensus. He found ‘do you like this’ had a low degree of consensus; ‘is this beautiful?’ was higher; and ‘would you like to spend eternity with this?’ gave almost complete unanimity. He was framing the questions so as to get people to think gradually more about the nature of beauty, and when he did, there was consensus.

And finally do I like it? So it’s not that taste is completely unimportant, but that it is just one aspect of choosing.

If the answer to all of these is yes I choose it. Even then, does this mean that I have made an infallible choice? No. As I mentioned before, there is no visible standard of perfect beauty by which I can measure something on any verifiable ‘beauty-scale’. God who is pure beauty is the standard, and I can’t see Him. However, what this does do by using reason to some degree, is to increase my chances of getting it right.

If I was choosing a piece for a public viewing, and especially a work of art for a church, I would play safe and seek not only those works that passed the above criteria when I consider my own opinion, but also for which there is a broad consensus that they are good, true and beautiful. How do I know which these are? Tradition tells me. Tradition is Chesterton’s democracy of the dead – taking the highest proportion of yesses, when considering all time, and not just the present. So for liturgical art, the authentic traditions are the styles of the iconographic, the gothic and the baroque. These styles have passed the test of time and I would choose art in these forms.

One last point, art is like food in another way. The more I am exposed to what is good, the more I learn to like it. My taste can be educated. So the more I expose myself to traditional art, the better my taste will become. Just as the more I eat salad, the more I will like it and the maybe one day I will grow out of Cheezy Wotsits…although I hope that day never comes.

David Clayton's Blog

- David Clayton's profile

- 4 followers