David Clayton's Blog, page 11

July 5, 2016

Why the Live-Aid Industry is Perpetuating Western Imperialism and Keeping Africans Poor

The methods of the poverty aid industry reflect their prejudices against faith in God, freedom and entrepreneurship – the very things that have created the wealth of the West. The effects of this hypocrisy is catastrophic both culturally and economically for the poor countries of the world.

I have just returned from the Acton Institute annual conference, called Acton University. The Acton Institute exists to promote a free and virtuous society characterized by individual liberty and sustained by religious principles.

It is easy to believe that groups that convene to discuss free markets and business are all well-to-do business people talking about how to make lots of money. This couldn’t be further from the truth at Acton. The focus is almost exclusively on how to help the poor and how to promote a society in which all people flourish and all ways. There were many talks on the promotion of a culture of beauty for the good of the souls of all, for example. These are things that are effect rich and poor alike and are vitally important.

What struck me this year is not just that Acton not only offers a solution to poverty and human flourishing around the world; but that it might well offer the only way. This is a solution that trusts in the abilities of all people to solve their own problems if they have the environment in which they can flourish.

The opening address by Senegalese entrepreneur Magatte Wade who was urging people to stop giving money to NGOs and charities that channel fund to the developing world. They are (usually) well intentioned, but their effect on the developing world is to make the problem worse. Magatte was scathing, also about the influence of celebrity philanthropists who parachute into a situation, have the photo shoot with smiling children and then disappear. The effect is damaging to the culture because the paternalism that drives it tends to tell the people themselves that they can’t create wealth themselves and need handouts from the West.

The opening address by Senegalese entrepreneur Magatte Wade who was urging people to stop giving money to NGOs and charities that channel fund to the developing world. They are (usually) well intentioned, but their effect on the developing world is to make the problem worse. Magatte was scathing, also about the influence of celebrity philanthropists who parachute into a situation, have the photo shoot with smiling children and then disappear. The effect is damaging to the culture because the paternalism that drives it tends to tell the people themselves that they can’t create wealth themselves and need handouts from the West.

The evidence on the hopelessness of the West in their paternalistic approaches to fighting poverty in the last 50 years is overwhelming. Haiti, for example, has about the lowest standard of living in the world, and yet it has more NGOs (and I’m guessing, more high profile celebrity visits from nearby USA) per head of population than any other country in world.

The evidence is that what people need is personal freedom and the environment to create business. In additions there needs to be a legal framework that helps rather than hinders this entrepreneurial spirit where it exists. This means, on the whole, governments and government organizations should cease trying to impose answers on the poor, rather they should try to encourage the environment in which the people themselves create the wealth.

If there is one thing that can be done in these countries, Magatte, told us, it is to help change the legal environments so that it is easier to do business. Education about this is part of it. There is an index listed by the World Bank called Ease of Doing Business. This index does not give the whole story. What this rating does not reveal are the intangible aspects of a society that will drive the entrepreneurial spirit most powerfully, faith and freedom. What it does tell us is that if the necessary aspects of a society are present then the legal framework in that country will not stifle development. Nevertheless, it is revealing I think to look at the correlation between ease of doing business and poverty in any particular country.

Magatte was quick to point out that the businesses she wants to see are those that Westerners want to see – any that offer real jobs, including global businesses not just ‘micro-invesments’. All these specialist types of investment and business models come out of the development industry too. It’s not so much that they are bad things in themselves, but they are pushed largely because they are seen as forms of entrepreneurial activity that do not offend the prejudices of the development workers who on the whole, to put it simply, as Magatte told us, ‘hate business’. And again, the losers here are the poor themselves who are cut off from the whole range of conventional investment models.

Furthermore, the assumption that where business flourishes, the human spirit is depressed is simply false. The conditions for entrepreneurship are the same as those for overall human flourishing – faith and freedom, the conditions for greatest entrepreneurial activity benefit the whole human person, body and soul! This is not just about money, but when you’re poor, it must include money.

The cultural and economic effect of the current aid model is to perpetuate the values of the aid workers, which are characteristic of the West, and to keep the West richer relative to those those countries in which they operate. It is another form of Western imperialism.

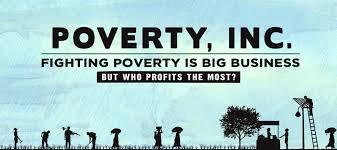

At the same conference was screening of a film produced by Acton, Poverty, Inc. which is now on wide release (and is just available on Netflix). Magatte appears in this film. This film, which has won many awards and has been praised by many from both the political left and the political right, supports Magatte’s account. I would recommend all to watch it.

July 1, 2016

Why the Mainstream Media Hide the Real Reasons for Poverty and Unrest in Venezuala

The plight of this country has little to with drop in oil prices and more to do with chronic economic mismanagement by a corrupt socialist government.

The plight of this country has little to with drop in oil prices and more to do with chronic economic mismanagement by a corrupt socialist government.

If ever a country provides a case of the evils, and I mean evils, of socialism it is Venezuela. A mere 30 years after the collapse of Soviet Russian we see centralized government actions done in the name of the people which have lead to the suffering of millions.There are food shortages, violence, unrest, and roaming government inspired vigilantes terrorizing the population into submission.

And, what, you might ask has this got to do with a blog called the Way of Beauty? The answer is that it was first the decline in the culture of faith that allowed the socialists to gain power in the first place. Venezuela shows that beauty and faith are things that matter for these are the values that bind a society together stably and for the greater flourishing of all people. I will come to this later in this article.

What was once a flourishing democracy collapsed into poverty and anarchy within 15 years because the introduction of socialist policies. Yet this is a story that is barely covered in the news and the reason is that it doesn’t correspond to the narrative of those who run the media outlets. If Venezuela gets a mention at all in the large media outlets, for example on the BBC website, then the country’s problems are attributed to the drop in oil prices. This is a complete misrepresentation and it is a terrible glossing over of the real cause of the problems, which were present before the oil price dropped. They can be attributed to what can only be described as brain-dead economic policies that began with the dictator Chavez and which his successor Maduro only made worse. Guided by Cuban advisors, they have succeeded in bring the country to its knees faster even than Cuba managed it themselves and starting from a position of much higher prosperity. Chavez, was always viewed positively by the media in Britain and it seems that they can’t bring themselves to admit now how wrong they were.

I was reminded of this recently when I attended the Action Institute annual conference, Acton University, in Grand Rapids, Michigan. The mission of the Acton Institute is to promote a free and virtuous society characterized by individual liberty and sustained by religious principles. They are concerned for the poor and oppressed and

In his address to those present, Kris Mauren, one of the co-founders of the Acton Institute, gave special mention to the plight of Venezuela today and said just this. Acton is one of the few organizations that is prepared to talk about this and they understand. There were several Venezuelans present at the conference and I spoke to them about this and they recognized with gratitude that here was one place that understood the problems their country was going through.

I told them also of my concern and prayers for their country (I pray to Our Lady of Coromoto, the patroness everyday). I wished I could do more. I sent them a link to an article I had written about Venezuela. The articles is here: How A Loss of Faith Can Lead to the Reduction of Freedom and Economic Properity. This explains how important the culture of faith and beauty is in maintaining a stable society in which the human person can flourish, and how when this is undermined, there can be terrible consequences.

It was revealing to hear the Venezuelans present at Acton describe with such sadness the terrible situation in their country and how its plight seems to be ignored by the rest of the world for largely ideological reasons. Here is the letter I received from one of these Venezuelan attendees after the conference – I have removed all personal details to protect him. The greater sadness is that since I wrote this article, 18 months ago, the situation has only got worse:

Dear David,

Thank you for keeping in touch after we met in Acton University. I read your articles and found them spot-on and inspiring. For us it’s important that other people around the world share our situation. There is no doubt that inequality/poverty is a fertile ground for these populist regimes to arise, this can happen in any developing country. However I never thought it could happen to Venezuela!!! Now we are in the middle of a struggle to get rid of this corrupt government.

Our president and others around him thinks (or makes people think) they are catholic but in reality they are fascist, evil people that don’t care about the suffering of the poor, only about remaining in power. You mention this in your article and it is really true. You also mention that Venezuelans are very family oriented which is also true. So many of my friends and co-workers have decided to leave the country looking for a better future; I don’t want to but I keep asking myself if that is the best way to secure a prosperous future for me and my family.

I’ll keep checking your blog from time to time to stay in touch and if you need any information or if you come to Venezuela (not really a good idea now…) let me know.

Take care,

[Name removed]

As requested by this man, I am posting this to promote their cause. Other than that I can only close with my daily call to the patroness of Venezuela, Our Lady of Coromoto, and I ask you to pray also to Our Lady for the people of Venezuela and all the poor throughout the world.

June 28, 2016

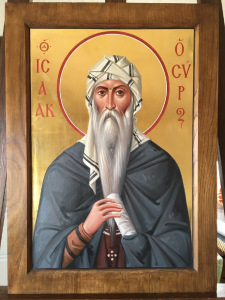

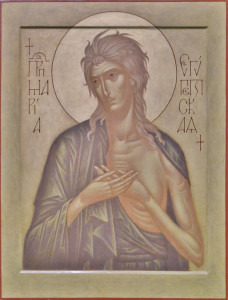

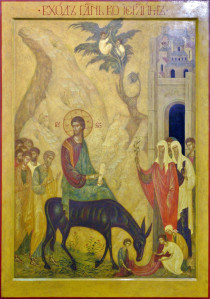

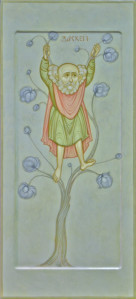

Modern Russian Iconographers Who Break the Rules but Conform to the Principles

Thanks to Gina Switzer (an artist whose decorated Easter candles have been featured on the NLM to great interest) for drawing my attention to this write-up in the Orthodox Arts Journal of an exhibition that took place in Moscow earlier this year, a presentation of contemporary Russian icon painters.

Thanks to Gina Switzer (an artist whose decorated Easter candles have been featured on the NLM to great interest) for drawing my attention to this write-up in the Orthodox Arts Journal of an exhibition that took place in Moscow earlier this year, a presentation of contemporary Russian icon painters.

What is interesting is the variety of styles on dsiplay that nevertheless all sit within bounds of what could legitimately be considered a holy icon. Many incorporate stylistic features that might not have been seen in the icons of Rublev in the 15th century. I would characterize what they are doing in the following way: the artist may be breaking past rules, but they never contravene the timeless principles that define the tradition. In the way I am using these words, a “rule” is precise and unbending, the particular application of a “principle” suited to a particular time and place. For example, a rule would be “only use gold for the background in an icon,” which is what I was told when I first started to learn iconography. The underlying principle, on the other hand, is flexible, and is applied in different ways according the needs of the time and place. The principle behind the use of gold for backgrounds is that the background must seem flat and not create the illusion of space, in order to suggest the heavenly realm which is outside time and space. If you look at such icons, you see a variety of background colors and even geometric patterned art, something I was told in my first icon classes should never be seen in an icon! However, they can all be used to suggest flatness, and therefore work well in conforming to the underlying principle.

Similarly, when I first learned icon painting I was told that I had to start with a dark background, and then build the form by putting successive layers of lighter toned paint on top; there was even a theological argument used to justify this. Then it was discovered that ancient iconographers used a method whereby a monochrome underpainting was laid down first, and then both light and dark transparent layers washes of paint were put over it. Because the end result – what the final icon actually looks like – was the most important principle, my icon-painting teacher immediately adopted this quicker and easier method of building form.

This flexibility is the sign of a vibrant living tradition, one in which individual expression is allowed, but always in conformity to the principles that define it. As a result, the tradition reinvents itself with each new generation and so is able to connect with the people of its day. No tradition can rely exclusively on its canon of past works to maintain its relevance; it must always create anew, or else it will die.

This is what Benedict XVI calls for in his analysis of culture in his book, Sing a New Song, in which he explains that it is the responsibility of the artist to connect with people beyond the esoteric circle of the artists and academics who “understand” the tradition. In Benedict’s phrase, he must connect with “the many.” Furthermore, he says that it is “the mark of true creativity” that the artist is able to do this. In other words, the responsibility of the artist is to be popular by creating good and beautiful works of art.

Art that is popular isn’t necessarily good, but the very best art will be popular. If the most popular aspects of mass culture today are not edifying and uplifting, then it is the responsibility of Christian artists to produce work that is and which, importantly, connects with modern people. If the artists fail to do so, the fault lies not with the audience, but with the artists for failing to create something that is beautiful enough to command a decent price. This simple test of quality is often seen as too harsh, and I find that there is resistance to it from practicing artists, especially those whose work doesn’t sell.

It is to the credit to those who in the mid-20th century reestablished the iconographic tradition in its modern form, that they laid down the foundational principle that allowed for the right sort of flexibility, and so created a living tradition. These people were Russian ex-pats living in France in the mid-20th century, most notably Vladimir Lossky and Leonid Ouspensky. Lossky was a theologian, Ouspensky was a practicing artist as well as a deep thinker. A third artist whose work was influential in the same regard was Gregory Kroug.

Oupensky and Lossky had to develop the greater part of these principles themselves. There were no detailed writings about art by the Church Fathers that they could draw on to define the stylistic elements in the way that was necessary to guide artists, and which anyone who has done an icon class will hear from his teacher. They analysed icons that they judged to be good and holy, and developed a theology of form that seemed consistent with what they were looking at. This is what artists needed in order to create work. The principles of this newly established iconographic tradition tell us not so much what artists did in the past, but rather what artists ought to do in the future in order to produce work that bears the mark of the holy icon.

The test of the validity of this is not historical accuracy of the principles as proposed, but rather the quality of the work produced by the artists who follow them, and the resilience of the tradition they established – can it outlast the generation that created it? We simply don’t know if the formulae that Ouspensky and Lossky developed correspond precisely to what Rublev would have been aiming for hundreds of years ago.

I feel that iconography has passed the test. We are now several generations of teachers and students past Ouspensky. The very best of today’s icon painters are producing icons in this style that stand alongside the great works of the past. and moreover, they are engaging with modern people in the place where they are meant to, in the context of the liturgy.

The analysis of these 20th century Russian ex-pats may very well have little credibility in the art history departments of our secular universities, where, I am guessing, it would be dismissed as purely personal speculation. But that doesn’t prevent what they proposed from being good and valid, given the end that they had in mind, namely, the creation of beautiful art that is in harmony with the liturgy.

I have to admit that I do not know how flexible Ouspensky and Lossky were themselves in their presentation of this. I once had some excellent classes from someone who was taught directly by Ouspensky in Paris, and who constantly referred to him. The instructions of how to do it were presented as inviolable laws; there was no room for discussion, and from the way that she described Ouspensky, it seems this is how it was presented to her. Nevertheless, she did explain the reason for the rule in each case. Once we understand why we are doing something – the end towards which the rule is directed – then regardless of how flexible Ouspensky would have been himself, this builds the possibility of changes that can be justified, provided they bring about the same end.

Even if we discover in the future that these principles are at variance with those used centuries ago – perhaps with the discovery of the some set of ancient scrolls – this in no way alters the validity of what has been developed in the 20th century. It simply gives us an alternative set of principles available to the artist who wishes to paint for the Church.

We can look to this pattern for reestablishing artistic traditions in the Western Church too. There are different things we can do. First is to work within the iconographic style and produce styles that connect with those who worship in the Roman Rite. Icon painters such as Aidan Hart have been doing this. Aidan is Orthodox, but he looks for inspiration to the styles of the Church in the West prior to the schism that were consistent with the iconographic prototype, such as the Romanesque. As a result, he is creating a 21st century style of Western iconography that connects with worshipers in the West, who worship in both the Roman and Byzantine Rites. Moreover, he passes the Benedict XVI “creativity test” – his work connects with the many and is in great demand.

The other thing that we can do is apply the Ouspensky/Lossky type of analysis to the other liturgical traditions of the Roman Church, the Gothic and the Baroque. St John Paul II understood this, and for this reason called in his Letter to Artists for a renewed dialogue between the Church and artists. The final section of my book The Way of Beauty is my attempt to do just this. You can judge for yourself the validity of what I propose, but regardless, we need our own Losskys and Ouspenkys in the Roman Church!

I present my favorites from the article – for the credits for the artists go to the Orthodox Art Journal. The one name I will mention here is the painter of the first icon below, Fr Zinon, who is perhaps the most famous icon painter of the present day.

June 27, 2016

A Book that Explains What the Brexit Referendum Was Really About

How to Be a Conservative by Roger Scruton and the cultural battle for the West.

How to Be a Conservative by Roger Scruton and the cultural battle for the West.

If you are like me and fed up of all the news articles and Facebook posts telling you that your support for Brexit reveals you as racist, jingoistic, selfish, economically illiterate, small minded or just plain stupid, then I have the antidote for you: Roger Scruton’s How to Be a Conservative.

In this small book he offers a brilliantly thought out practical philosophy of moral and compassionate patriotism, that cares deeply about the liberty and floursihing of poor and the rich alike, and sees a culture of beauty as absolutely necessary to transmit and sustain the core principles and values that bind the nation together (and frankly, make life worth living). It is a religion neutral, natural-law case for a just society that is, as far as I can tell, consistent with Catholic social teaching. Scruton is an Englishman and his discussion is mostly in reference to the English situation; however, he admires and visits the US regularly as well and at various points he adapts what he is saying to the American situation.

His is a philosophical argument, that is, one that is argued rationally from the starting point of observations how people are. He is an acute observer of human nature and so his arguments convince by appealing to ordinary to common sense as much as anything else. He tells us first that his conserative instincts came in part from his father, whom he observed growing up in High Wickham in southern post-War England. Jack Scrution, we are told, was a committed socialist who sought the redistribution of wealth, but, as Scruton junior pointed out, ‘we are all conservative about the things we know about’. And what his dad knew about and loved was local history, and especially the beautiful architecture and the area around High Wickham in Buckinghamshire. This love of the local heritage compelled him to campaign for the preservation these beautiful signs and symbols of traditional English culture and way of life.

Now in his seventies (and made a Knight in the Queen’s 90th birthday honours list!) Sir Roger Scruton still follows his fathers instincts in this regard even though he never shared his political views. He has had a long academic career which began as an undergraduate at Cambridge, but which steadily saw him become an independent academic as it was obvious that he had no career in the faculties of the universities of England, dominated as they are by a left wing and intolerant intelligentsia.

Now in his seventies (and made a Knight in the Queen’s 90th birthday honours list!) Sir Roger Scruton still follows his fathers instincts in this regard even though he never shared his political views. He has had a long academic career which began as an undergraduate at Cambridge, but which steadily saw him become an independent academic as it was obvious that he had no career in the faculties of the universities of England, dominated as they are by a left wing and intolerant intelligentsia.

He does not seem the slightest bit bitter however, his writing exudes a gentle and optimistic outlook and it it is clear that he understands and accepts that no men are perfect, liberal or conservative, believing or nonbelieving.

Scruton does not tells us his personal religious beliefs, for this is philosophy, not theology. Nevertheless, his is a philosophy that sees the necessity of both religion and religious tolerance. Faith is seed ground from which grow the mores that every society must have in common if people are to feel that they belong to it. And in the West, that pattern of living is dominated by Christianity.

The picture of a society that he builds up with this natural law approach is, as far as I can tell, consistent with Catholic social teaching. One could have as easily quoted St Thomas on the natural virtues of religion, of family piety and devotion to nation to support his conclusions if the desire was to persuade Catholics of the point, but he has a wider audience in mind.

Scruton is a cultural conservative as well as political and economic. Culture is important in his philosophy because it is the pattern of daily living that communicates the mores of the society to the non-religious in a way in which they can absorb them naturally and comfortably, without being forced to be adherents to the religion. It is culture that is the principle of inclusion and which makes a country nation – a society in which the citizens feel they belong. It is the beauty of a national culture that tells its citizens that ‘they are at home in the world’.

Furthermore it is tradition, the steadily developing accumulation of what is good from the past, that passes on that culture to us. This is why the conservative spirit always respects what we have and even if critical, looks for modification rather than revolution. It seeks to improve by building on what is good, even in the worst situations, rather than by destroying the present in order to reinstute the past, or a new future.

And for Scruton, society is not an arbitary grouping. Man has a natural inclination to associate with others, which he must be allowed to do freely and those associations – the clubs, societies, sports clubs and so on are the sub-cultures that together form the national culture. The most important associations that are common to all people are faith, family and nation. Even those who are not people of faith, he argues, will in the well ordered society subscribe passively to it by participating in the culture of faith that binds that nation together.

This is why supra-national projects such as the European Union will always fail – without a common culture to keep them together eith either they will fragment as the national cultures within its artificial border clash; or will have to resort to tyranny to stop it happening, as happened in the former Yugoslavia and will happen in he EU if it does not disintegrate first (we can only hope).

It is also why a strict multiculturalism in which there is no absorption of the cultural practices of immigrants into a the national culture, but separation and the formation of ghettoes on non British cultures within the national boundaries. During the Brexit debate, some of the intellectual elite who seek to destroy traditional British culture deride those who wish to preserve a sense of Britishness in Britain as jingoistic, racist and ingnorant. But it is natural for those who care about Britain as it has been to wish to retain a cultural identity. What gave the greivances of those who are not happy with the changes even greater legitimacy is that the British had no choice in whether or not those changes were made. The changes were being imposed on us by the law created by unelected beaurocrats who were not themselves British and so naturally didn’t care at all about the cultural concersn of those who live there.

To object to these changes does not automatically make someone racist or even anti-immigrant (though no doubt some were both). Immigration is not a problem provided those who come are willing to become culturally British. This is not racism or jingoism, but a natural and legitimate response for anyone who loves his country. The ad hominem attacks that those who dare to talk of the value of traditional British culture have to put up with tell us a great deal about what their accusers and their attitudes, figures such as Bod Geldoff an Irishman who shouted and gestured at out of work Cornish fishermen on the Thames, feel about British culture.

All cultures and subcultures are the aggregated effect of personal interractions and so are always formed from the bottom up. It is one of the great paradoxes of man and society that individual actions that are driven by free will, and therefore apparently random and sitting outside the natural order that is described by the scientific laws of cause and effect, but they can nevertheless give rise to a discernible pattern and order when the society as a whole is observed. Generally the best influence of government can have on a culture is to protect personal liberty and allow it to emerge naturally. Top down attempts to manipulate the cultural forms directly by directing personal interraction with law are likely to stifle personal freedom and the human spirit. This in turn leads to a dimunition of human flourishing, both spiritually and economically. It is why socialism is such an ugly and dismal failure in this regard.

Scruton is well aware that when people claim rights of action and freedoms for themselves, it will lead to clashes. He gives an example where the rights of travellers (people who in the mast might have been referred to pejoratively as tinkers or gypsies) to settle where they wish clash with the property rights of those who live close to where the travellers choose to settle. We might think also of the case where the right of the unborn clashes with the claimed right of the woman to choose to have an abortion. This is where custom, or in the extreme the law must decide whose right or whose freedom has preeminance; and it a justice system that is rooted in a consensus of morality that will do that effectively and happily. He maintains that religion is the only viable and sustaining source of morality that works for the benefit of that society, even for the non-religious within it. In Britain this is the basis of common law.

In his critique of today’s post modern society, Scruton still manages, consistent with his conservative ethos, to be constructive by looking for the positive as well. Chapter by chapter he analyses the institutions and ideas of today, the various “isms” – nationalism, socialism, capitalism, liberalism, multiculturalism, environmentalism, and internationalism so as to highlight goods to be retained as well as the bad to be discarded. So the chapter titles are, for example, - ‘The Good in Nationalism’, ‘The Good in Socialism’, ‘The Good in Environmentalism’ and so on. He persuades us with good humored reason, and does not try to goad us on with firey rhetoric. And through this analysis he paints a vision of a possible society that does not perfect human nature, but rather accommodates it, with all its flaws and imperfections. He promises no utopia, but rather a realistic prospect of something better.

He builds up his ideas by drawing largely on the philosophy of Aristotle and the Englightenment philosophers such as Burke, Hegel, Adam Smith and Kant and sells it to us through his witty and entertaining writing and the obvious love he has for his own country. As a Catholic I was intrigued at how much the ideas of the Englightenment and Kant espeically, which are not universally admired in Catholic circles (to put it mildly), could nevertheless be helpful.

Intrigued I wanted to know more and wondered if I was going to have to write another chapter for Scruton’s book for Catholics called, ‘The Truth in the Englightenment and the Truth in Emmanual Kant’.

Never one to read a large amount of 18th century philosophy if I can avoid it, I started look around to see if someone had done it first. It was Benedict XVI’s little book on the subject of Europe, Christianity and the Crisis of Cultures that saved me the effort. Benedict too draws on Kant and Enlightenment thinkng in his analysis.

In regard to the Enlightenment he tells us:

‘The Enlightenment has a Christian origin and it was not by chance that it was born specifically and exclusively within the sphere of the Christian faith, in places where Christianity, contrary to its own nature, had unfortunately become mere tradition and the religion of the state. Philosophy, as the investigation of the rational element (which includes the rational element of our faith) had always been a positive element in Christianity, but the voice of reason had become excessively tame. It was and remains the merit of the Enlightenment to have drawn attention afresh to these original Christian values and to have given reason back its own voice. In its Constitution on the Church in the Modern World, the Second Vatican Council restated this profound harmony between Christianity and the Enlightenment, seeking to achieve a genuine reconciliation between the Church and modernity, which is the great patrimony of which both parties must take care.’[p48]

One flaw of the Englightenment, Benedict tells us, is that it cuts itself off from ‘its own historical roots, depriving itself from the powerful sources from which it sprang. It detaches itself from what me might call its basic memory of mankind, without which reason loses its orientation.’ [p41]

And in regard to Kant he tells us:

‘The search for this kind of reassuring certainty, something that could go unchallenged despite all the disgreements, has not succeeded. Not even Kant’s truly stupendous endeavours managed to create the necessary certainty that would be shared by all. Kant had denied that God could be known with the sphere of pure reason, but at the same time, he had presented God, freedom, and immortality of postulates of practical reason, without which he saw no coherent possibility of acting in a moral manner. I wonder if the situation of today’s world might not make us return to the idea that Kant was right. Let me put this in different terms: the attempt, carried to extremes to shape human affairs to the total exclusion of God leads us more and more to the brink of the abyss, toward the utter anihilation of man. We must therefore reverse the axiom of the Enlightenment and say: Even the one who does not succeed in finding the path God ought nevertheless to try to live and to direct his life, as if God did exist. This is the advice that Pascal gave to his friends and it is the advice that I should like to give to our friends today who do not believe. This does not impose limitations on freedom, it gives support to all our human affairs and supplies a criterion of which human life stands sorely in need.’ [p51]

So Benedict, too is a conservative whose instincts tell him not to destroy, but to amend society, building on the best of what he have. Furthermore, it seems to me that Scruton has provided just the template for a way forward towards a society that is in accord with what Benedicti advises. It is through the instutions of the nation state, the family, and religion with an attitude of tolerance of non believers, that we can have a society bound by a common culture that society that, if not perfect, is free enough and beautiful enough that we can at least feel ‘at home in the world’ to quote Scruton.

Afterword: three days after the Brexit referendum as I write this, and the bitterness and division is not subsiding. This indicates to me that although the issue is multifaceted and the points of debate are most commonly economics and immigration at its heart it is a battle for a worldview and this is why at times the two sides seem to be arguing past each other. One party is rooted in the faith of a Judeo-Christian society and which, as explained, may include those who have no faith but subscribe, broadly speaking, to the values. The other is rooted in post-Englightenment secular humanism which is marked at this stage by a dislike of Christianity and Christian values above all else (even though some Christians subscribe to it, unthinkingly in my view).

The referendum was for the right to sovereignty and a battle against European imperialism driven by unelected and unaccountable beaurocrasts pushing their secular humanist agenda. Even assuming that Brexit does actually happen (and I’m not convinced that all the forces opposed to it will respect it) there is still no guarantee that the hopes of conservatives will prevail. The forces that wish to change it are still strong and will continue to do all they can to argue for their point of view. But at least now this is a British debate and there is some chance that as the nation decides itw own destiney, for the sort of conservatism that Scrution describes to prevail, where previously there was none. I for one am glad about that.

June 24, 2016

Anglican Ordinariate Liturgy at Sacra Liturgia 2016; and Other Ordinariate and Sacra Liturgia Matters

Just a couple of weeks before Sacra Liturgia 2016 I would like to mention a couple of things that caught my eye.

First is that once again the conference is promoting the liturgy of the Anglican Ordinariates. When I attended Sacra Liturgia 2014 in Rome I was heartened by the welcome that priests from the Ordinariates were given, as I wrote in an article, here, in which I said also why I think that their creation is so important for the whole Church.

I am please that the openness to the Anglican Use continues and that in the program of liturgy for the conference there will be a ‘Solemn Mass (Divine Worship – Ordinariate Use)’ on Friday 8th July at 7pm at the Church of Our Lady of the Assumption and St Gregory, Warwick Street, London W1B 5LZ. Celebrant and preacher will be Mgr Keith Newton, the Ordinary of the Personal Ordinariate of the Our Lady of Walsingham.

Most liturgies for the conference are taking place at the Brompton Oratory. This program includes a Solemn Pontifical Mass in the Ordinary Form celebrated by Robert Cardinal Sarah, Prefect of the Congregation for Divine Worship and Discipline of the Sacraments. The music will be by the London Oratory School Schola Cantorum directed by our own Charles Cole.

My own conversion to Catholicism was influenced profoundly by stumbling into a beautiful Latin Mass in the Ordinary Form at the Brompton Oratory over 25 years ago I am pleased to see this and so much of the conference liturgy at this church.

The point should be made that the program of the liturgy is open to all, not just those attending the conference. The full program of liturgies is here. The photo below is of an Anglican Ordinariate liturgy in Baltimore.

On another Anglican Ordinariates matter, I was lucky enough recently to bump into Fr Edward Tomlinson of the Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham at a conference in, of all places, Grand Rapids, Michigan (We were at the annual conference of the Acton Institute). Fr Tomlinson and I were both attending the EF Latin Mass which was offered at the conference and he introduced himself because I had my copy of the Customary of Our Lady of Walsingham under my arm. He told me of his CTS booklet about Ordinariates. This is an excellent short introduction for people who have questions about the Ordinariates and the reasons for their creation. Fr Tomlinson has written it with both curious non-Ordinariate Catholics and curious Anglicans in the UK in mind and so his answers refer to the Personal Ordinariate or Our Lady in Walsingham in particular.

I will quote one page from the booklet about the liturgy of the Ordinariates, simply because it addresses questions that cropped up on this blog when I posted an article about the Customary:

Does the Ordinariate have its own liturgical rites? Yes. Ordinariate texts exist for use in public and private worship. Ordinariate services are, of course, open to all.

What is the purpose of a distinct Ordinariate liturgy? Ordinariate liturgy exists to encourage an ‘Anglican patrimony’ – that is worship reflecting an English and Celtic spirituality, to connect Catholic liturgical life in the present with its pre-Reformation existence, reminding Britain that she was in truth, formed and forged in a rich Catholic culture.

Are the Ordinariate texts mandatory? No. Being a full part of the Latin Rite, Ordinariate groups and priests are free to choose between the Ordinariate resources for worship and those of the wider Church.

What is the Customary of Our Lady of Walsingham? The Customary is the ‘office book’ of the Ordinariate, that is to say it provides texts for Morning and Evening Prayer and other similar celebrations. Accessing aspects of the Book of Common Prayer, so familiar to Anglicans, it places heavy emphasis on readings from the English and Celtic saints to remind us of our pre-Reformation history.

The booklet is available from CTS here.

June 21, 2016

Dominican School Offers Formation for Artists- Now Including Sacred Geometry and English Gothic Illumination Practicum

Here is a reminder (with some additional details) of a four-course certificate intended as a formation for artists in any creative discipline. It is an exciting new course offered by the The Dominican School of Philosophy and Theology, which is part of the Graduate Theological Union at Berkeley University in California. The Certificate in Theological Studies is a Master’s level, four-course (12-unit) certificate which is recommended for those who already have a working knowledge of a specific art medium (visual arts, music, architecture etc.), and wish to augment their expertise with a specialized focus in the relationship of the fine arts to Catholic worship and culture. These courses are open to people not otherwise studying at the DSPT.

The new information is that I have been invited to teach the elective in the Spring 2017. I will teach a practical course which will include the creation of a gothic image in the style of illuminations of the 13th century School of St Albans; and sacred geometry. In the geometry course, students will construct a traditional geometric pattern as used in cosmati floors of the period. In support of the practical skills I will teach the supporting theory as described in my book, the Way of Beauty.

The approach to this certificate program assumes the “cross-disciplinary approach” between philosophy and theology that uniquely characterizes all DSPT curricula. Furthermore, in this particular program there will be a focus on the integration of theory with praxis, particularly as it applies to Catholic worship and culture. An emphasis on the outcomes of this course is on the evangelization of the culture through a well discerned engagement with contemporary cultures, so that the creativity of the artist may be directed towards the engagement of contemporary man, without any compromise of the core principles of a traditional Christian culture.

The Certificate program of studies is organized by the Academic Dean of the DSPT, Fr Chris Renz; readers may remember that I highlighted his excellent article on liturgy and culture recently published in Antiphon.

Fr Renz will use my book the Way of Beauty as one of the texts for the opening course of the Certificate program. Anyone who has read any of my writings over the years will see why I am enthusiastic about this – these themes of inculturation, worship and fresh creativity are at the heart of my own ideas about the evangelization of the culture.

The first course of the four to be offered this coming Fall is called the Foundational Principles of Catholic Liturgy and Worship. To complete the Certificate in Theological Studies program with a specialization in Sacred Arts, the student must complete the four courses indicated below, typically over two or more semesters.

1. Foundational Principles of Catholic Liturgy and Worship (next offered Fall 2016)

2. Liturgical Piety: Anthropological Foundations of Catholic Worship (next offered Spring 2017)

3. One elective offering from any advisor-approved Religion and the Arts course. These are the courses that will particularly focus on practical elements, such as painting.

4. Christian Iconography (offered Fall 2016)

The format for all courses is once per week for just under 3 hours. They will typically offered during the weekday, which means that you have to be within striking distance of Berkeley, California in order to take it.

The named outcomes are to:

• imbue students with an understanding of sacred art and its relationship to sacred liturgy;

• provide students with the philosophical and theological foundations for the anthropological as well as the transcendent aspects of art;

• provide basic principles for using the fine arts as a vehicle for “preaching the gospel” to the contemporary culture.

Application Process

Applicants must complete the DSPT Certificate of Theological Studies application (found at the DSPT website), including a statement of purpose, official transcript, and two letters of recommendation. Application is on a rolling admission process.

Tuition and Fees

Tuition rate for 2016-2017 academic year is $715 per semester unit (all courses are 3 units). For further information, contact Fr. Chris Renz, O.P. at crenz@dspt.edu, or 510-883-2084. You can read about this course on the DSPT website at www.dspt.edu/sacred-arts

June 13, 2016

Artists – Please Learn to Draw

One of the most common shortcomings in the works of artists today is poor drawing ability. There is a perception among some, especially if working in the highly symbolic styles of the gothic, the iconographic or even the style featured recently, the Beuronese style, that the artist can hide his lack of technical skill behind the stylistic elements. I have heard people say that they signed up for icon painting classes for example, because they think that they don’t need to be so good at drawing.

One of the most common shortcomings in the works of artists today is poor drawing ability. There is a perception among some, especially if working in the highly symbolic styles of the gothic, the iconographic or even the style featured recently, the Beuronese style, that the artist can hide his lack of technical skill behind the stylistic elements. I have heard people say that they signed up for icon painting classes for example, because they think that they don’t need to be so good at drawing.

The same thing happens in mainstream arts schools, students opt for Expressionistic styles because they know that they can’t be held to account for how bad the drawing is – they can hide the lack of skill behind wild and flamboyant brush strokes. Many just forgo the paintbrush altogether, pick up a video camera and go for conceptual art.

This may be acceptable in the context of 20th century art styles, but I suggest this is not good enough for sacred art, no matter what style we want to work in.

In fact it is more difficult to work within a particular tradition and retain accuracy in drawing. It requires the artist to understand both where he must be precise in reflecting nature, and where he must be precise in deviating from natural appearances in accordance with the demands of the style of the tradition.

Artists quite often show me their work and one of the usual comments I make is, you need to improve your drawing. It is great that there are more and more people who are looking to traditional forms as inspiration for sacred art and so I always want to be encouraging. There is hope, drawing is a skill that can be taught. Someone who wants to learn to draw can spend time learning the academic method of drawing – this trains the eye to observe nature and then to render it in two dimensions. Another thing to consider is an illustrators’ course, in which one can learn how to create new images without always having to set up a tableau of figures posing for the image. At some point the good artist does need to be able to go beyond simply drawing what he can see. He must be able to draw what is in his imagination too.

Here are two examples of faults that I often see. I don’t like highlighting what is bad in other peoples’ work, so I’ll use examples of mine to illustrate (I have plenty to choose from!)

The first is the drapery of cloth. In sacred art, the figures are often portrayed with draped clothing. It is vital that the folds in the cloth look natural and that there is a sense of a properly proportioned figure underneath. The only way to understand this that I know is to study how material drapes over the human form. One of my frustrations when I was studying academic art was that we spent so much time studying the nude, but none devoted to studying clothes. This would have helped me.

Have a look at this painting of St Silouan the Athonite. At first glance, the folds in the cloth look natural, but if you look closer you can see that the deep red robe is done incorrectly in the region between the arms. The reason is that I didn’t really understand what I was supposed to be painting and so just guessed.

In fact, it the red robe should have been doing what St Hubert’s is below (in Aidan Hart’s icon), hanging in a U shape between the arms.

and then the figure is rotated for a three quarter profile view as in this figure of Elizabeth Prout shown below. Aidan Hart has shown it with the line drawing in black on a plain brown robe rendered without additional shading or highlights.

If we want the figure to look natural underneath the drapery then there are certain pressure points at which the clothing is supported by the figure or otherwise directly acted upon by the figure, while else where it hangs free. This will usually be places such as the shoulders, elbows, knees and the crook in the elbow. If these pressure points are not place absolutely precisely the whole figure looks wrong.

We can see how well John Singer Sargent does this in the painting below, a portrait of Mrs Henry White. So much of the dress is swirling away from direct contact with her body. This means that in order for it to look as though it belongs to her he has very few of these pressure points to work with, but these must be absolutely right. In this case the shoulders and the tight fitting waist and her hips. Her left hip indicated with a tiny little detail, a conjunction of shadow and highlight. If these were not absolutely correct, the eye of the observer would pick it up instantly and everything would look wrong.

Another common area of error is in the drawing of the proportions of hands and faces. In the example below, I copied a famous icon of St Matthew. When I showed it to my teacher, Aidan, he instantly pointed out that his right hand looked distorted. I replied that I noticed this but thought that this was how it had looked in the original. Because I didn’t know if I was allowed to change it, I had left it exactly as I thought it had been done by the original artist. (I believed that when I said it, but now that I looked at it, I wonder if I copied inaccurately as well! you can see the original below and judge for yourself). Aidan immediately replied that it didn’t matter and if the original looked like that too, then the original was done badly and I should be copying errors unthinkingly. Here’s the point: just because we are working in the iconographic style it doesn’t mean that we accept anatomical inaccuracy. The goal is to be both anatomically correct and to work with the iconographic style, this is what all the great icon painters are able to do.

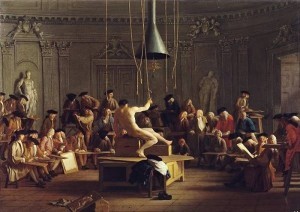

The image at the top is the Drawing Class by Sweerts (Dutch, 17th century)

June 7, 2016

Moments of Vision, A Poem by Andrew Thornton-Norris

Andrew Thornton-Norris offers readers his new poem, Moments of Vision, along with an explanation of its composition. An Englishman based in the west of England, whose work is admired and published on both sides of the Atlantic, Andrew teaches literature and poetry at Pontifex.University.

Andrew wrote an earlier blog posting called ‘Redeeming Romanticism‘ by which he meant raising the purpose, or end of the genre to something higher, what it ought to be. In this poem he gives an example of what he was describing. I find it fascinating how he brings modern ideas of form into what has at its heart a traditional structure.

Moments of Vision

1. The Apophatic (After T.E. Hulme)

O moon hanging there not lighting up

The darkness but just leaving it obscure,

Reflecting light that’s hidden for a time:

You are the blessed sacrament that shines

Upon the darkness of their majesty.

2. Helen’s Face

The female body is the battlefield

In the war that’s taking place between

The Word, the world, the devil and the flesh:

The judgement cast upon it, lust that it

Betrays and crimes that are committed there.

3. The Hymn of the Nuptial Mystery

In intimate relation we are in

Eternal intimate relationship

Within our souls and beating in our hearts

The passion of transcendent being back

Together that we thought we’d left behind.

4. Lent

The Forty Days and Forty Nights is when

God’s Kingdom is the desert where we meet

Him in the hidden fasting and the prayer

That separates us from the world outside

And brings us to the peace of penitence.

5. Dead Souls

All beauty’s holy and eternal and

Destroyed by commodification,

Which brings it back to dust in an

Embittered fall from heaven earthward but

The hope of faith is in the Death of God.

6. The Flower Bed

When I went back to the place where I

Had slept and saw the mess of lying there

I felt forboding of the grave and rushed

To get away but now I see perhaps

One heaven sent and love to contemplate.

7. WWW

When the whole world and all its life

And history is here to hand and at

The touch or click upon a button then

The only way to turn to get away

Is inwards, walk into the world within.

8. Sapperton Tunnel

Between the catchment of the Severn and

The Thames, the way of life is different,

The valley sides that crumble down into

The houses flowing streamward down below,

Suggestive of the valley of the Wye.

9. The Passion of the Lord is the Birth of Love

As fires from tiny flames great cities fell

My love for you began with just a glance

A word and then the conflagration grew

Until the world was all aflame like stars

That fall from skies above into our hearts.

10. The Walled Garden

Narcissus, yellow archangel, and then,

Because of sympathetic magic, so

Called lungwort: metaphysicians of the spring;

But why are winter snowdrops purest white,

O winter what has happened to your sting?

Brief note for students

This poem deals again with the subject of central concern to me: the deepest longings of the human heart, for love, joy, and peace for example, their frustrations, and how these experiences are most perfectly responded to, of any available belief system, by Catholicism. Its form is ten titled sentences of blank verse or unrhymed iambic pentameter. I chose this form because this is roughly how the ideas for the individual stanzas came to me as a group all around the same time. The idea of collage, or collection of disparate elements arranged around an overall theme rather than a logical narrative or argumentative structure is a modernist technique employed in other arts as well. Here it is combined with the most traditional form of English verse. The overall title is from a collection of poems published by Thomas Hardy in 1917.He is the last representative of a peculiarly English late-Romanticism, described as the last words of a dying protestantism by John Powell Ward in his book, The English Line. That line begins with Milton and only Philip Larkin was to attempt its resuscitation, describing himself as an “Anglican atheist”. In Catholic terms, the title represents the moments of vision or contemplation when the pure of heart see God. It is therefore an attempt to redeem the Romantic form and subject through re-establishing the proper relationship of art to religion that I described in the last post.

May 30, 2016

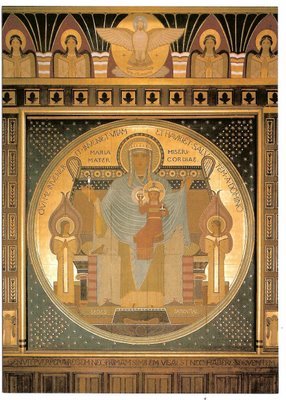

The 19th Century Beuronese School, An Inspiration for Artists Today?

I have become aware over the last couple of years of contemporary artists looking to the 19th century Beuronese school for inspiration when painting for the liturgy. Time will be ultimate test of how appropriate this is, but my initial reaction is that this is good thing. I thought that I would give some thoughts as to why I think this.

Stylistically, Beuronese school is an interesting cul-de-sac that sits outside the mainstream of the Christian tradition. It is named after the town of Beuron in Germany which is the location of the Benedictine community in which the school originated in the mid-19th century.

The most well known artists who painted in this style in Europe are Desiderius Lenz (d 1928) and Gabriel Wuger (d 1892). In the United States, the walls and the ceiling of the abbey church of the Benedictines at Conception Abbey in Missouri, are decorated primarily with authentic examples of the Beuronese style. The abbey website tells us that the work was done between 1893 and 1897, by several monks of Conception, most notably Lukas Etlin (d. 1927), Hildebrand Roseler (d. 1923), and Ildephonse Kuhn (d. 1921), the latter two of whom had studied art at Beuron.

The original Beuronese artists were reacting against what was the dominant form of sacred art being painted for the churches of the Roman Rite at the time. This dominant style was an overly naturalistic and sentimental form of academic art, the product of the French academies and ateliers. The most well known artist of this decadent form is probably the Frenchman Bougeureaux. (For an in-depth discussion of this over naturalism in academic art read Is Some Sacred Art Too Naturalistic?)

Authentic Christian art has a style that is always a carefully worked out balance of naturalism (sometimes referred to as ‘realism’) and idealism. The naturalism in art tells us visually what is being painted – put simply if you want to paint a man it must look like a man, with a human body and limbs and so on. The idealistic element of the style is a controlled deviation from strict adherence to natural appearances by which the artist reveals invisible truths. The invisible truths that the artist might reveal, though style, are that man has a soul and a spirit that is intellect and will, for example.

It is this deviation from strict ‘photographic’ naturalism that characterizes the style of art (although in reality even a camera lens distorts appearances in a way that causes a photograph to be subtly different from what the eye actually sees). All paintings in any particular tradition will have in common particular methods of controlled abstraction that are carefully worked out to reveal the Christian understanding of what it portrayed. It is through perception of these that we are able to recognise the style. For example, we recognise the iconographic style because of, for example, an enlargement of the eyes, the dimunition of the mouth, and the elongation of the nose, in a particular way. These elements of iconographic style were developed to suggest to the observer a particular characteristics in the person portrayed that are appropriate for a saint.

It is as easy to distort appearances to hide truth and to create the equivalent of a visual lie through style, incidentally. Many advertising hoardings have photographs that are composed and then usually ‘airbrushed’ – that is, deliberately distorted – so as to to exaggerate in an imbalanced way the aspect of sexual attraction (and so, it is believed, sell products). This tells us that it is not enough to stylize, the Christian artist has a great responsbility and must understand deeply how his stylization is going to reveal truth, rather than hide it. If he gets it wrong he can lead souls astray. It’s not just what he paints, it’s how he paints it. (I hesitated to portray the image, below right, which I see as an example of art that has an anti-ideal. It is about at the limit of what I feel I can show and even then I felt I had to make is small.. Bear in mind it is intended for a children’s comic.)

Aware of the deficiencies of the sacred (and mundane art) of their own time, Beuronese art sought to introduce an idealization into their style by seeking inspiration from ancient Egyptian art and from the Greek ideal. Visually it is easy to see the influence of the Egyptian papyri; but in addition the Beuronese artists used a canon of proportion that was said to be derived from that of the ancient Greeks (although this is speculative on their part, given that the canon of Polyclitus is lost). The link between ancient Greek art and Egyptian art is not an unnatural one. Plato praised the Egyptian style and it has been speculated that Greek art from the classical period (around 500 BC) was influenced by Egyptian art. The Beuronese artists themselves were trained in the methods of the19th century atelier and the result is a curious mixture, 19th century naturalism stiffened up, so to speak, by an injection of what they believed to be Egyptian art and Greek geometry.

What of the painting of Beuronese art today? In his encyclical about the sacred liturgy, Mediator Dei, Pius XII made it clear (in paragraph 195) that we should always be open to different styles of art for the liturgy provided any style under consideration: has the right balance of naturalism and idealism (he uses the words ‘realism’ and ‘symbolism’ to refer to these qualities); and that what drives its use is the need of the Christian community and not the whim of the artist or patron. In my experience, the Bueronese style does connect with people today in the right way so that it is appropriate for the liturgy. It has the sufficient naturalism so that one can recognise easily what they are looking at; and sufficient idealism that it does suggest another world beyond this one. Furthermore, contemporary culture does seem to provide naturally enough cultural reference points to allow modern people, even those without a classical education, to relate to this style. Art deco architecture, for example, is also derived from Egyptian styles. Strangely, many might find the Beuronese style with its Egyptian roots more accessible than a traditional icon in the classic Russian style of Andrei Rublev.

I have read an account of the geometric proportions used in the human form in translation of the book written by their main theorist Fr Desiderius Lenz, On the Aesthetic of Beuron. It was so complex that my reaction was that it would be very difficult for any painter to use the canon succesfully in any but very formal poses. As soon as an artist seeks to twist and turn a pose in the image, then the necessary foreshortening requires the painter to use an intuitive sense as to how the more distant parts relate to the nearer. Usually this means that in these cases he is less able to adhere to the cannon of proportion so well. This might account for that fact that when the figures are in less stiff and formal, Bueronese art seems to work less well, in my opinion. To my eye, the more relaxed poses produce art that looks like illustrations from the bible I was given when I was a child. Good in that context, perhaps, but too naturalistic for the liturgy I would say.

The approach of original Beuronese school is idiosyncratic – I do not know of any other Christian style of liturgical art that looked to ancient Egypt for inspiriation. Nevertheless the end result, when done well, does strike me as having something of the sacred to it and being worthy of attention. Perhaps their efforts to control the modern temptation to individual expression have contributed to this too. The school stressed, for example, the value of imitation of prototypes above the production of works originating in any one artist, furthermore the artists collaborated on works and did not sign it once finished.

Note, the icon detail is from a contemporary icon at St John the Baptist, Euless, TX, painted by Vladimir Grygorenk

Below I show some examples of Beuronese art that I think are less successful than the examples above. The first is less formal and ends up looking like a good illustration for a children’s bible, but not so good for the liturgy, I suggest.

The next is highly skilled, but a little to close to 19th century naturalism for my liking.

May 25, 2016

A Pattern for Catholic Education that Places the Liturgy at Its Heart

When I decided I wanted to be an artist, I started to investigate the training that was given traditionally to artists in the past. This involved the study of a number of things: how the skills of the art, painting and drawing for example, were transmitted; the great works of Catholic culture so that the artists understands the tradition in which he is working; and a formation of the person, so that he is open to inspiration, and can apprehend beauty and work beautifully.

When I decided I wanted to be an artist, I started to investigate the training that was given traditionally to artists in the past. This involved the study of a number of things: how the skills of the art, painting and drawing for example, were transmitted; the great works of Catholic culture so that the artists understands the tradition in which he is working; and a formation of the person, so that he is open to inspiration, and can apprehend beauty and work beautifully.

This article is an attempt to articulate concisely what I discovered (and describe in greater length in the book the Way of Beauty) – that a formation in beauty, was not only part of a general Catholic education, but in fact was identical with what a general Catholic education ought to be, and so rarely is.

The only difference between an artist’s education and any good general education was the vocational element, in this case painting. It occurred to me that this could change according to the particular calling of each person. Then the rest would benefit every person, regardless of his precise calling in life and could complement all other study and human activity.

I believe also, incidentally, that this is a program that could be also a formation of people as evangelists who can participate in the New Evangelization, shining with the Light of Christ as they go about their daily business.

The content of the syllabus, which I do not describe in detail here is superficially similar to many humanities and liberal arts educations. However, in contrast to many of these existing educations (the ones that I have looked at, at least), it emphasizes in its pedagogical method more strongly what I see as an essential element, that of praxis - putting into practice what is learnt and so developing the faculty of the creativity by creating beautiful things..

The other key element – perhaps the most important – is that of consciously ordering of everything to man’s ultimate end and relating it to the highest form of praxis – the worship of God.

Teachers and students alike should be able to make the connection between any element of study and our purpose in life. Then the teachers know the answer to the question, why teach? And students know the answer to the question, why learn? And each will be motivated all the more to fulfill their role.

I will outline the pedagogical method first, and then articulate my understanding of what a Catholic education is. Finally I will list some quotations from Church documents that emphasize the points that I am making in regard to the goal of a Catholic education:

Pedagogical method

1. Wonder – the appreciation of divine beauty The first stage is to inspire in the student a natural and personal response to the divine beauty which is present in creation and in the beautiful works of man in both the culture of faith and the wider culture. This response should be a natural and joyful experience.

2. Intellectual Illumination – imparting knowledge and understanding This aspect examines how the good, the true and the beautiful participate in all that exists and are personified in God. As much as communicating the subjects taught – eg the liberal arts, philosophy and theology – a goal is to train people to think both analytically and synthetically so that we set them on a path of lifelong learning which they can direct themselves. By ‘analytically’ I mean examining the parts of the subject; by synthetically I mean understanding the whole in the light of what we know about the parts. The broadest synthetic thought is that which places all that we know in the context of our whole human life and its purpose.

3. Praxis 1 – creating a culture of beauty. First by imitating the most beautiful parts of the culture – eg the works of masters, with understanding. Second, by creating original works in art, music, literature etc. and so contributing to the culture.

4. Praxis 2 - participatio actuosa - active participation in the sacred liturgy: the realization of ‘liturgical man’. Teaching people the practice of the worship of God and all it entails. When students take these lessons to heart, participation in the liturgy becomes the ultimate act of creativity, by which they enter into the mystery of the Trinity and by grace participate in the creative love of God.

What is a Catholic education?

The aim of all Catholic education is to offer students a formation that might lead to supernatural transformation in Christ that each might be capable, by God’s grace, of movement towards their ultimate end, and of contribution to the good of each society of which each is a member.

All other stated ends in education, for example, the re-ordering of society’s culture, of bearing witness to Christ in their surroundings and the training of skills to enable the student to earn a living, while necessary are nevertheless ordered to this ultimate end and achieved in their fullest measure by this supernatural transformation.

It is common in the field of Catholic education to cite the creation of the virtuous person as a goal. This is true, and it is in effect another way of saying the same thing, for the highest virtue is a cardinal virtue, the virtue of religion. According to St Thomas (ST II-II, Q.lxxxi) it is a virtue whose purpose is to render God the worship due to Him as the source of all being and the principle of all government of things. It is a distinct virtue, not merely an aspect of another.

This supernatural transformation, made possible by baptism, is made real by an encounter with the living God. This encounter can happen in many ways but occurs most profoundly and most powerfully in the Eucharist and by it we are made capable in a new way, through God’s grace, of loving Him and our fellow man. Love of our fellow man in all its forms is inseparably bound up with love of God: the encounter with God in the Eucharist renews our capacity for love of neighbor; and love of neighbor tends to deepen our participation in the worship of God in the Eucharist.

So profound is this connection between love of God and love of neighbor that there is no authentically human activity – thought or deed, sacred or mundane – that cannot be formed by and ordered to the Eucharist for the better of each person, society and the Church. In this sense the Eucharist is the form (as in guiding principle) of every aspect of the Christian life including all those pertaining to a Catholic school.

Any school or educational institution therefore should ensure that all that goes on is in accord with the end of all education. Accordingly, it should ensure that students are aware that their capacity to be educated and that every aspect of their lives as Christians, whatever their personal goals, will be enhanced when they participate actively in the Eucharist and live a liturgically formed life. This knowledge will help to motivate students in their studies and order all their activities to their personal goals in life, which in turn are ordered to their ultimate end.

Each student should be clearly aware of the profound desirability of a supernatural Christian transformation and, therefore, the need for grace in their education, as in all human activity; and that the Sacred Liturgy is the optimal encounter with Christ in this life that provides for this need. There are many ways that Christ can be encountered, and every activity of a school should be such an encounter of one form or another. However, each encounter, if it is real, points to and is derived from that optimal encounter in Sacred Liturgy. Students should be aware that the fruits of such a transformed Christian life, which are promised to us, are precisely those that a Christian education aims to provide in the ideal.

As well as imparting an understanding of the primary importance of the Sacred Liturgy as the form of their everyday lives and in their education, students need to be given religious instruction so that each, in accordance with his personal situation, might develop a sacramental life that will make the transformation possible. This religious instruction includes principles by which they can develop a harmonious balance of liturgical prayer, both the Mass and the Divine Office, devotional and personal prayer in which the non-liturgical elements are derived from and point to participation in Sacred Liturgy. By this instruction they will know, in theory at least, what is necessary continually to deepen their participation in the sacramental life, with the Eucharist at its heart; and continually to renew and increase their capacity for love of neighbor.

While it may be appropriate for the instruction of what is just described to be given to all in the classroom, the actual participation in the liturgically centered sacramental life must always be one that is voluntary. We must respect each person’s God-given freedom to choose. Transformation itself can neither be taught nor enforced: it is derived from a personal and free response to God’s love for us. The participation therefore, should be encouraged. Accordingly, the role of the school is to increase the freedom of each person to choose well by enhancing their knowledge of what is good in this regard and giving them, where humanly possible, the power and opportunity do to do so. In accord with this the college should make it a priority to make beautiful and appropriately celebrated Sacred Liturgy available to the students in a beautiful place of worship. Ideally the faculty will lead by example, so that their actions speak of the centrality of the Eucharist in a life well lived.

All subjects included in the curriculum, while not all relating directly to the subject of the Sacred Liturgy, must nevertheless be consistent with these twofold and inter-connected aims of love of God and love of man, consummated in a freely chosen liturgically oriented piety. Each faculty member should be able to explain the reason for the inclusion of the subject taught in the light of these principles and willingly direct the students to its liturgical end.

Moreover, beyond the classroom the college should strive to encourage a culture in which any aspect of community life is in accord with and reinforces its ultimate goals for the students.

Quotations from documents on education:

‘A school is a privileged place in which, through a living encounter with a cultural inheritance, integral formation occurs.’ (The Catholic School, 26; pub The Sacred Congregation for Catholic Education, 1977)

‘The proper and immediate end of Christian education is to cooperate with divine grace in forming the true and perfect Christian, that is, to form Christ Himself in those regenerated by Baptism…For precisely this reason, Christian education takes in the whole aggregate of human life, physical and spiritual, intellectual and moral, individual, domestic and social, not with a view of reducing it in any way, but in order to elevate, regulate and perfect it, in accordance with the example and teaching of Christ. Hence the true Christian, product of Christian education, is the supernatural man who thinks, judges and acts constantly and consistently in accordance with right reason illumined by the supernatural light of the example and teaching of Christ; in other words, to use the current term, the true and finished man of character.’ (Pius XI, Divini Illius Magistri, 60; Encyclical on Christian Education, 1929, 94, 95, 96)

‘The integral formation of the human person, which is the purpose of education, includes the development of all the human faculties of the students, together with preparation for professional life, formation of ethical and social awareness, becoming aware of the transcendental, and religious education. Every school, and every educator in the school, ought to be striving to form strong and responsible individuals, who are capable of making free and correct choices .’ (Lay Catholics in Schools: Witnesses to Faith, 17; pub Sacred Congregation for Catholic Education, 1982)

‘No less than other schools does the Catholic school pursue cultural goals and the human formation of youth. But its proper function is to create for the school community a special atmosphere animated by the Gospel spirit of freedom and charity, to help youth grow according to the new creatures they were made through baptism as they develop their own personalities, and finally to order the whole of human culture to the news of salvation so that the knowledge the students gradually acquire of the world, life and man is illumined by faith.’ (Paul VI, Gravissimum Educationis, 8)

‘For a true education aims at the formation of the human person in the pursuit of his ultimate end and of the good of the societies of which, as man, he is a member, and in whose obligations, as an adult, he will share.’ (Paul VI, Gravissimum Educationis, 1)

‘First and foremost every Catholic educational institution is a place to encounter the living God who in Jesus Christ reveals his transforming love and truth’ (Benedict XVI, Meeting with Catholic Educators, Catholic University of America, Washington DC, April 2008)