Rebecca Stonehill's Blog, page 67

June 5, 2015

Fighting back against Kenya’s alleged ‘non-reading’ culture

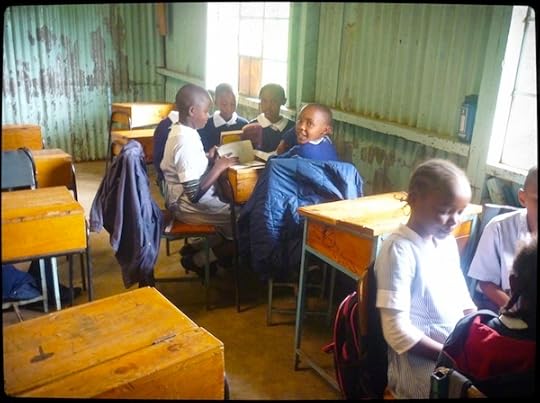

A couple of weeks ago, I ran a creative writing session in a school with about twenty 10 and 11 year old’s. This is the place where I do voluntary work about once a fortnight and the kinds of writing exercises I get the kids to do is received with anything ranging from incredulity to liberation to pure terror (the Kenyan education system, also known as 8-4-4, is known for rote learning, nutty numbers of exams and not much outlet for creativity.) That’s ok, I just try to run with whatever comes up and encourage them to get something on paper by the end of the session, stressing that there is categorically no right or wrong.

This particular day, I took a box of books in with me and we did my ‘First Line of a Story’ exercise, whereby each child is given a book and then in small groups they discuss which first line they like best, and why. As a class, we go on to discuss different elements of what makes a great first line and how we need to instantly capture the attention of the reader and reel them in, before everybody has a go at writing their own corker of a first line.

Let me digress a little here to say that it is very, very hard to get hold of decent, affordable books here in Kenya. I’ve often heard people say that there simply isn’t a reading culture here, one of the reasons for this being because of the tradition that has been passed orally from one generation to another so that this oral folklore remains well and truly alive in such a way that in other cultures it is all but dead. I know, for example, that amongst the Kikuyu (Kenya’s largest ethnic group), until a couple of generations ago, it was completely normal and expected that each and every member of the tribe from a very young age could recite the names and stories of each of their ancestors going all the way back to Mumbi, the figure regarded as the ‘mother’ of the Kikuyu.

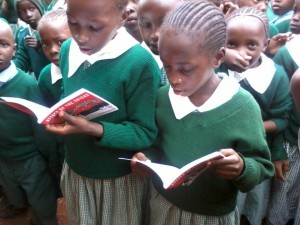

Don’t get me wrong, the art of storytelling is valuable and necessary. Yet isn’t it a little (or a lot?) defeatist to say there isn’t a reading culture here, and more than that, it can be used as an excuse for the relevant government departments to not encourage reading and essentially, provide books to school children. Back to the class of kids I was working with that day, let me tell you that getting them to relinquish the books at the end of the session was HARD. They all crowded round the box, overjoyed to be given free reign, for a short while at least, to all these books and new worlds. This was not a class full of children interested only in their oral tradition of stories, these were kids excited and overwhelmed by books, something we so take for granted in the West. I’d argue that by putting a great story into the hands of any child, the world over, a door is being opened to possibility, to imagination and to empowerment.

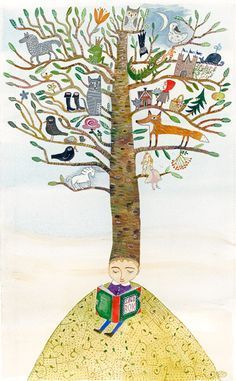

From Oliver Jeffers The Heart and the Bottle

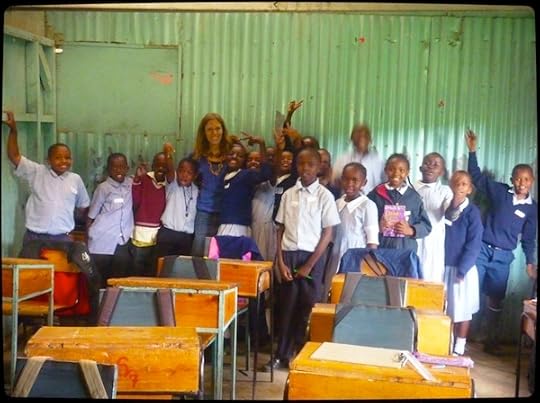

On that note, it’s brilliant to see that here in Kenya non-profit organisations exist to counter this ‘non-reading’ culture. Kudos to both of them, Grab A Book and Start A Library.

A tiny bit more about them, as taken from their websites:

Carolyne Kimari (founder) is a 2013 Kenyan Spark* Changemaker. Her organisation, Grab a Book, works to set up libraries in slums and rural areas providing children with access to quality age-appropriate books and after-school and weekend tutoring.

Start A Library is a Reading Revolution campaign initiated by Storymoja intended to: 1. Excite children about reading for pleasure through our Read Aloud events and Reading clubs 2. Increase access to books by forming or stocking libraries in Primary Schools. There are more than 20,000 primary schools in Kenya without libraries. In two years, SAL has started 51 libraries in schools and centres across Kenya.

Psssst…whilst I’m on this particular bandwagon, though not in Kenya (but Malawi, Zambia, Ecuador & Galapagos) I couldn’t not mention the fabulous Book Bus that trundles around delivering books to schools and inspiring children to read. LOVE IT. Particularly because all these buses are gorgeously decorated with iconic Quentin Blake paintings – could it get any better?

The post Fighting back against Kenya’s alleged ‘non-reading’ culture appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.

May 30, 2015

Music as a creative force in writing

Katie Basil Screenprint

I come from a family in which music is very important. Last week I wrote about the healing power of music as written about and illustrated in Quentin Blake’s gorgeous children’s book Patrick. As I was growing up, everyone in my extended family played at least one or two instruments, lauded over by my musician grandmother who was a violinist, pianist, organist and singer amongst some of her musical accomplishments. As for me, over the years I have played recorder (ha! haven’t we all?), cello, piano, ukelele and guitar. Next on my list is the oboe which I am just longing to learn, and learn I shall once I have the time (or, rather, when I prioritise it, I should say.) A good way I can check in with myself and my emotional state of mind is to observe how much I sing or hum to myself – it’s like an internal happiness barometer – when things are out of sync, I find I stop singing.

ME Ologeanu mixed media collage

But what does all this have to do with writing? Well, a surprising amount. I’ve always been interested in the connection between what we write and what we hear; in other words, if music can influence to write from a different place, more expressively and expansively. Many years ago, whilst teaching an advanced English language class to a bunch of TEFL students, I veered away from the syllabus (ever in search of creative outlets for myself) and brought in my ipod and speakers, playing some music for them to write to. They produced some of their best written work I’d seen from them. And then, more recently, with a creative writing session for a couple of teenage boys, I was inspired by this article on ‘Using ‘music writing’ to trigger creativity, awareness and motivation’. The boys were not impressed when I started to play the slightly spacey music suggested by the writer of the article and spent ten minutes moaning and chewing the end of their pencils. I could see we weren’t getting far, so switched it to some jazz. The effect was instantaneous: both their heads dropped to the page and they began to furiously scribble.

John Lee Hooker

As for novel writing, some people need complete silence to write in. Others welcome familiar, comforting sounds: ticking clocks, the swirling hisses of coffee machines, the hum of background chatter. I need music personally, but not just any old music. What I do is create on spotify a playlist for the novel I’m working on (how did I exist before spotify?), music that just ‘works’ with the plot. What I find as a result of this is that when I come to sit down at the laptop for my next writing session, the minute I put this same music on, I can drop far more quickly back into my writing zone, connecting with the characters and landscapes. There’s really no formula to this but for me, it’s nothing short of magic.

What happens is that the music conjures an image, or a series of images in my head and then I write them down. The characters don’t tell me what they are saying, but they start moving and their movement can lead to actions or to words. I don’t really know how else I can explain this, but I’m telling you, music works…at least, it does for me, in a more powerful way than anything else.

To give you a small taste of my playlists, for The Poet’s Wife a song I often listened to was El Quinto Regimiento (The Fifth Regiment) by Lila Downs. If you understand Spanish, the lyrics of the song tell an interesting story about the start of the Spanish Civil War. Even if you don’t, this video is worth a watch as the song is set against some interesting old photographs of the war.

As for my current novel, I have a playlist with a number of pieces of instrumental music on it (no singing), but there are two in particular I have got stuck on and sometimes (this may sound nuts) I spend an entire morning writing with a single piece of music on repeat, playing over and over and over again. I never get bored of it. In fact, it helps me to write in a way that nothing else can. Here is one of the pieces, the sublime ‘On the nature of daylight’ by Max Richter, set to a visual feast of the natural world’s splendour:

Novel number three? (Yes, this is also very much in progress) – expect blank spaces between the words to dance to the sounds of skiffle and Bob Dylan and Joni Mitchell and Jefferson Airplane. The soundtracks to all three novels couldn’t possibly more different because, of course, they inhabit different times and spaces and take on their own unique existences by the characters that walk through their pages.

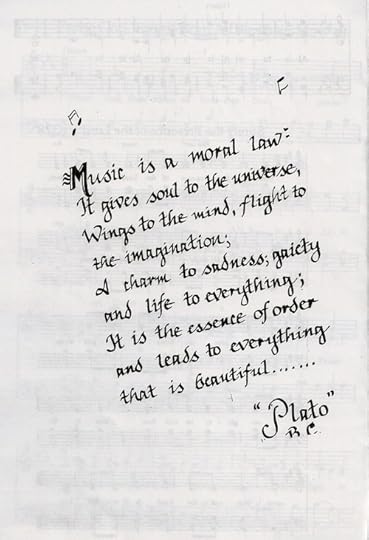

I’ll leave you with the words of Plato. And I’d like to add my own postscript to what he writes, and say that it does all the below and more: music helps to breathe life, dimension and dreams into my characters and make them every bit as real as you reading this and me writing it.

The post Music as a creative force in writing appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.

May 23, 2015

Book Review: Patrick

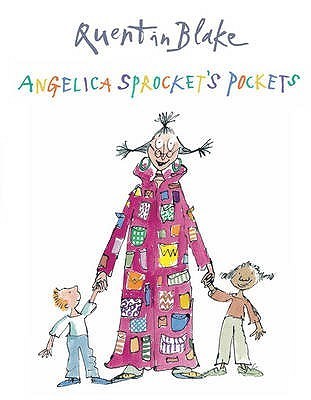

I think I must be on a Quentin Blake roll at the moment because in my last blog I talked about an activity I did with my creative writing club based on Angelica Sprocket’s Pockets. Blake’s first published drawing was for Satirical magazine Punch at the tender age of 16 and since then he has gone on to illustrate over three hundred books. Amongst his numerous activities, he is patron of the Nightingale Project whose mission is to put art into hospitals and fervent supporter of Survival International, indigenous rights NGO.

Today I’d like to talk a little about Patrick, Blake’s first colour illustrated book for children, published originally in 1968. We have a number of Quentin Blake books on our shelves but, to my mind, this is one of the most special.

Let me try and explain why.

There are a number of ways, equally valid, in which you can try to imbue a love of music to a child and what it has to offer the human spirit: You can play music, discover favourite songs and musicians together; you can encourage the learning of a musical instrument and watch and listen as your child improves with practice, little by little; you can take your children to the opera and the ballet and musical theatre and concerts of all genres, point them in the direction of a choir or a musical ensemble; you can buy books about classical music, about jazz, about different musical traditions from around the world and learn about Prokofiev and Miles Davis and Ali Farka Toure.

You know another thing you can do? You can read your children Patrick by Quentin Blake.

What’s so special about Patrick, you may well ask. Ok, let me tell you. It is the simple story of a young man who sets out one day from home to buy a violin. He reaches the second-hand market stall kept by Mr Onions which has ‘…a broken jug, an old lamp, a mouse-trap and all sorts of things that people did not want any more.’ It also has an old violin which Patrick promptly buys.

He couldn’t be any happier. When he sits down beside a pond he starts to play, but ‘…the most extraordinary thing happened. One by one the fish in the pond began to jump out and fly about in the air. And what is more, the were all different colours and they were singing to the music.’

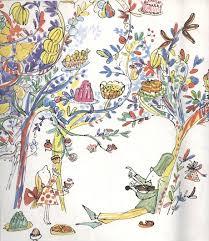

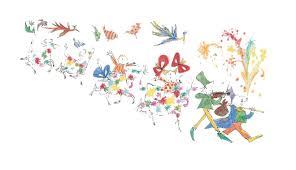

Patrick discovers that all kinds of amazing things happen when he plays music: the clothes of young children burst into riotous colour; instead of trees growing apples in an orchard, they sprout ‘…cakes and ice-creams and slices of hot buttered toast’; the feathers of birds are transformed and a whiskery old tramp blows out sparks of fireworks from his pipe.

But we have to wait until the end of the story for the pièce de résistance. For the travelling group of colourful merrymakers, led by Patrick, soon come across a tinker and his wife travelling on a horse and cart. The tinker is thin and drawn and clearly, not very well or cheerful.

‘Let me play my violin and see what happens,’ says Patrick.

So he does just this and the tinker grows fatter and healthier by the second, until he is utterly unrecognisable, as is his newly multi-coloured horse and cart. ‘The tinker and his wife climbed on, and so did Patrick and Kath and Mick and the whiskery tramp. The fish and the birds flew above them and the cows galloped along behind.’

Of course we shall not transform outwardly with such rapidity from hearing music that speaks to us, but Blake’s unmistakable message is that music can and does have the power to transform our lives, to heal and bind us to one another if we allow it to. And how do we do this? We simply open our ears to the world and find the right music.

Patrick is a gem that draws together art, prose and the reclaiming of our innate joie de vivre through the metamorphic gift of music.

The post Book Review: Patrick appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.

May 16, 2015

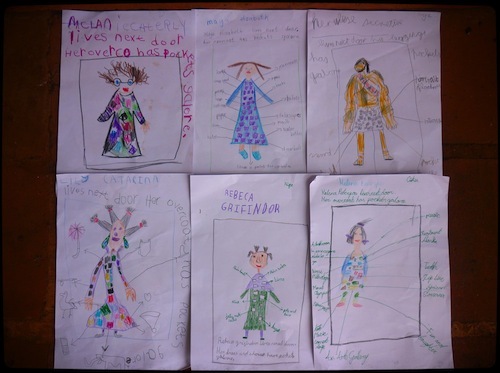

Having fun with Angelica Sprocket’s Pockets

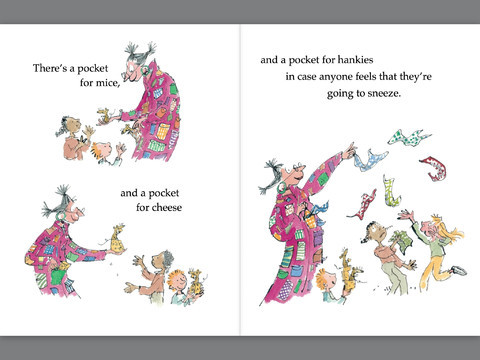

Angelica Sprocket’s Pockets is an infectiously fun story book written and illustrated by previous children’s laureate Quentin Blake. The wild-haired, eccentric Angelica Sprocket continually pulls one surprising item after another, Mary-Poppins-like, from one of the pockets of her overcoat, much to the delight of the crowd of children gathered around her.

I decided to use this story with my after-school club last week. After we’d read the whole story together which had the whole group in gales of laughter, I firstly asked the children to think of their own character with the same number of syllables as Angelica Sprocket. The idea I’d had was for the group to draw the picture of their character with lots of pockets on their coat and then draw lines coming from these and write in full sentences (rhyming if they were feeling in a rhyming mood) about the pockets’ contents. However, ideas sometimes don’t go quite to plan. What happened on this occasion was that the kids were enjoying drawing their pictures so much that we didn’t really reach the writing part. At least, some of them did but it was more words than sentences and certainly no rhyming going on.

But, you know what? There are times when you just have to go with the energy of the group and if they’re loving something that much, so be it. So this session was more creative drawing and less creative writing but that’s ok! They had a blast and anybody that can pull an elephant or the kitchen sink from a pocket with Angelica Sprocket’s flair is pretty classy in my books.

For the first time EVER during my Magic Pencil sessions in the garden, we were rained out last week and had to come inside…amazing it’s never happened before!

For the first time EVER during my Magic Pencil sessions in the garden, we were rained out last week and had to come inside…amazing it’s never happened before!

As an aside, after doing the session I found this resource for teaching ideas around Angelica Sprocket’s pockets for any teachers reading this, which includes an interview filmed with Quentin Blake himself.

The post Having fun with Angelica Sprocket’s Pockets appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.

May 9, 2015

Natalie Smithson: Unlocking our imagination with stories

Natalie Smithson is a freelance writer and creative at Bobbin About who specialises in work for parenting, children, and baby brands. Here she tells her story of how her active imagination as a child landed her in hot water, but went on to fuel her career as a writer.

Stories have been tampering with me since I was a little girl. Imagine, stepping into a secret world or going on an extraordinary adventure of epic proportions. My imagination carried me away into strange lands and unusual places. I was drawn in, page by page.

When I was tall enough to reach and extract the key from my Nan’s back door I wasn’t yet old enough to realise it had no magical power. Certain that the heavy, ginormous key unlocked a door to The Secret Garden, I took it home with me, over sixty miles.

Nan wasn’t best pleased.

The grown-ups were onto me when I discovered a teeny tiny door under her stairs. They showed me there was only a small cylinder hoover inside, but I wondered if Wonderland was palpable if I crawled within.

Books gave me a sense that there is something more beyond what we already know. Somewhere past the bland notion of happy-ever-after but before the cosmic exploration of sci-fi, I found myself nestled in with curious notions about truth and fiction.

Now, as a parent and step-parent, one of my greatest pleasures is the sound of laughter when an unexpected voice fills the room to adopt the character from a bedtime story.

A child’s complete attention when absorbed in a good book sits heavy as a blanket in winter, and the gong of recognition signals the mark of a child who is listening and growing.

Stories are a gateway for children to explore their own feelings and the greater world around them. Like most parents, I want to open as many doors as possible for them to choose their own path.

Who knows where it will lead?

When you’re small, it’s difficult to comprehend that the things you love most in the world are all created by someone.

Inventive works are presented on paper, on a screen, or accompanied by music, and the stories become renowned and adored. It’s not until we understand the creative process that we can credit the person who brought the original idea to life.

Being a writer always seemed fanciful to me as a child; these big stories with long words and enormous hearts. They were greater than anything I could conceive of at the time.

As I got older, I came to realise that they could all be broken down, word by word, and I put a full stop after the idea that I couldn’t be a writer.

I started to write a plan for my business.

Without the weight of possibility sitting on my mind, I might never have believed I could do it. Yet here I am, a writer, waiting to see the stories that the next generation paints across the sky.

The post Natalie Smithson: Unlocking our imagination with stories appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.

April 30, 2015

Book Review: The Story of Ferdinand

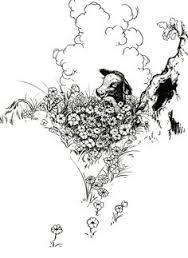

Written by the wonderfully named Munro Leaf and lovingly illustrated in black and white by Robert Lawson, The Story of Ferdinand, set in Spain, was first published in 1936, the same year that the Spanish Civil War (subject of my first novel, The Poet’s Wife!) truly erupted. Due to the sensitive timing of the book’s publication, at a time when fascism was rapidly spreading across Europe, Ferdinand, a gentle bull who prefers smelling flowers to bullfighting, caused considerable controversy as he was believed to represent a left-wing pacifist. Not only was the book burned as propaganda in Nazi Germany but it was also banned outright in Spain, a country embroiled in bitter civil war and edging further and further to the political right. The controversy continued, for Stalin granted it privileged in status in communist Russia whilst over in India, Ferdinand was said to number amongst Mahatma Gandhi’s favourite books.

Yet it matters not how many times Ferdinand was burned or banned, this book has been translated into over sixty languages and has never once gone out of print. When Leaf created this story (which he apparently wrote in a single sitting in a yellow legal pad so his friend Lawson would have something to illustrate), did he intend a subtle dig at the rise of fascism in Europe? He claims not; that he simply wanted to write something to entertain children. And reading it now, as I often do to my children, I must admit it is hard to understand what the fuss was once all about.

Ferdinand is a gentle soul who enjoys nothing more than sitting quietly and alone beneath his favourite cork tree all day. All the other little bulls he lived with would run and jump and butt their heads together, but not Ferdinand. He liked to sit just quietly and smell the flowers. When five men arrive at the pasture one day to find the toughest bull to fight in the ring in Madrid, whilst all the other bulls do their best to win the men over, unfortunately for Ferdinand, he doesn’t look where he’s sitting and places his behind firmly on a bee (above picture.) Ferdinand jumped up with a snort. He ran around puffing and snorting, butting and pawing the ground as if he were crazy.

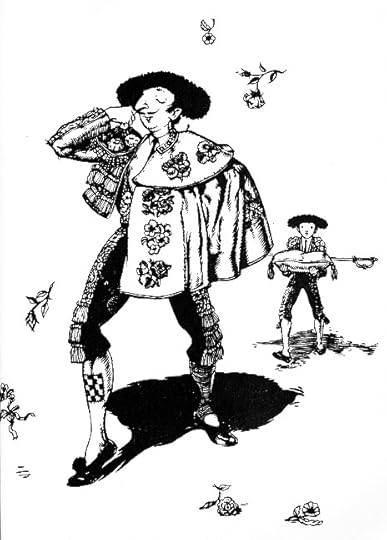

The unwitting Ferdiand gets picked and is carted off to Madrid where he is called Ferdinand the Fierce, everybody quaking in their boots at the imminent arrival of this terrifying beast in the bullring.

‘Then came the Matador, the proudest of all – he thought he was very handsome, and bowed to the ladies. He had a red cape and a sword and was supposed to stick the bull last of all.’

Ferdinand enters the bullring in something of a daze whilst the crowd clap and cheer, waiting for him to fiercely fight. But Ferdinand has other ideas. He has caught a scent of the flowers in the hair of all the lovely ladies, and he cannot quite help himself but sit down quietly and smell. Nothing that the matador does to try to provoke him entices him to fight. Oh no. He wouldn’t fight and be fierce no matter what they did. He just sat and smelled. And the Banderilleros were mad and the Picadores were madder and the Matador was so mad he cried because he couldn’t show off with his cape and sword.

Happily for Ferdinand, and unhappily for the Matador and bull-fighting fans, the gentle bull gets taken home to his pasture.

‘And for all I know,’ the story ends, ‘he is sitting there still, under his favourite cork tree, smelling the flowers just quietly.

He is very happy.’

This wonderful book is a classic that has stood the test of time, beloved to generations of children. As interesting as the purposeful or unintentional political connotations are, at heart The Story of Ferdinand is a celebratory tale of being different, standing apart from the crowd and the moral and philosophical implications of how we choose to interact with others.

The post Book Review: The Story of Ferdinand appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.

April 26, 2015

Sci Fi Writing for Kids

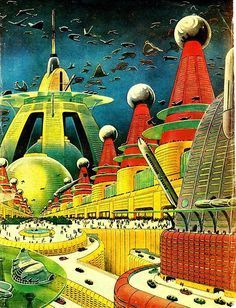

I approached Sci Fi writing for my creative writing club with some trepidation – I haven’t done much Sci Fi writing myself and I just wasn’t sure if they’d run with it. But how wrong could I be? All the kids loved it, and I mean loved it. We began the session by chatting in small groups about where we would visit if we could climb into a time machine (It was fun also to imagine exactly what this time machine would look like). As a group, we went on to discuss and note down the kinds of things that would be different about the past or the future, for example food, clothes, landscapes, technology & homes. I asked the children to climb into their time machine and be transported to the year 3000.

Using some or all of the variables we’d come up with, I asked the children to respond in writing, in either poetry or prose, to their new world in the year 3000. Fabulous! They couldn’t stop writing. We had changing-colour digital t-shirts that wash themselves whilst wearing them, people living in giant nests, plastic trees (living, breathing trees are extinct) and robotic birds to name but a few of the ideas. This was such an enjoyable activity, and I definitely mustn’t shy away from Sci Fi writing in the future as the children responded to it brilliantly.

The post Sci Fi Writing for Kids appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.

April 18, 2015

Age banding on books? No thanks

Illustration by Dasha Tolstikova for The Jacket by Kirsten Hall

There’s something very odd indeed about putting age bands on books. The message it’s really sending out is this: Don’t try and read above your age level, and if you read books for younger children, then you’re reading ‘below’ yourself. The point is, if a child wants to read, this needs to be encouraged on every level; whether they are reading ‘above’ or ‘below’ some arbitrary age bracketing is neither here nor there.

The rationale is, of course, that it is just ‘guidance’ for parents, teachers and children alike so that they are helped in their decisions on which books to pick up and which to leave. But it feels very prescriptive and is, I feel, doing a great disservice to young readers who need to find out for themselves what written word inspires and excites them. So this means not being pushed to read books their parents and teachers think they ‘ought’ to be reading. Of course this doesn’t mean suggestions shouldn’t be made and reading should be encouraged as much as possible but at the end of the day the decisions, as I said before, need to come from the children themselves.

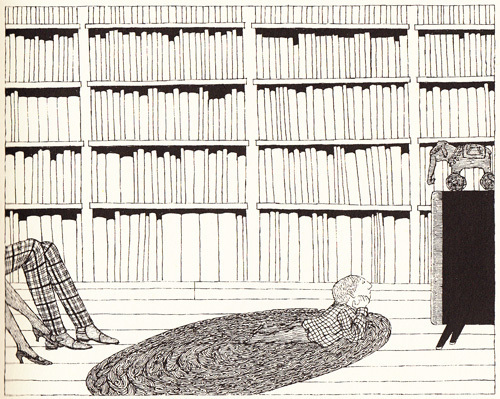

Illustration by Edward Gorey from The Shrinking of Treehorn

Harry Potter for example. There’s been a a whopping great amount of fuss about what age kids are emotionally mature enough to deal with some of the darker themes in the later books. But to suggest that all kids mature at the same level is nonsensical. Besides, there are so many books that can be read on different levels at various stages throughout one’s life. When my eldest child was seven, she read the first three Harry Potter books but when she reached the fourth, she got half way through and then, without giving any explanation, put it aside very quietly. No nightmares, no trauma. She didn’t need an adult to say anything, she quietly worked out on her own she wasn’t ready for it. One year later, and she’s read the whole series three or four times over. I have no doubt she’ll keep re-reading the series over the years to come and each time she does so, her increased age and maturity level will draw new depths from the material.

Illustration by Tom Seidmann-Freud, Sigmund Freud’s niece, from David the Dreamer

Conversely, on the other side of this, the same daughter and also my six year old enthusiastically listen to stories that are allegedly for ‘four year old’s’. I think that it is so, so important that there is no stigma attached to this and that no book should be perceived as being ‘babyish.’ Maurice Sendak, beloved writer and illustrator for ‘children’, famously said that ‘I don’t believe I have ever written a children’s book. I write – and somebody says, “That’s for children!” ‘ The point is: books are books are books. Let’s find our own paths with them. I, for example, am a thirty-seven year old woman who derives vast pleasure from pouring over books ‘intended’ for children. And how many of my generation can honestly say they never read an inappropriate Virginia Andrews or Danielle Steel book at the age of eleven? I think my parents would have been horrified to know what I was reading, but think of author Ben Okri’s timeless advice in his Ten and a half inclinations: Read the books your parents hate. And: Read what you’re not supposed to read. (For his full list click here). Do I regret reading those books when I was quite young? Of course I don’t!

Rådhusets Julkalender

I’m not alone in my anti-age banding ideas. A long time after I first realised I felt strongly about it, I discovered the ‘No to age banding‘ organisation, whose mission statement is:

‘…to put an age-banding figure on books for children is ill-conceived and damaging to the interests of young readers.’

Their petition to get rid of age-banding on books has been signed by many hundreds of people, including 832 authors (and yep, JK Rowling is amongst them). I’ll leave you with the wise words of writer Neil Gaiman that offers a cautionary message to parents and teachers, encouraging us all to give children the freedom to explore literature in whichever way that feels important and pertinent to them.

‘Well-meaning adults can easily destroy a child’s love of reading. Stop them reading what they enjoy or give them worthy-but-dull books that you like…you’ll wind up with a generation convinced that reading is uncool and, worse, unpleasant.’

The post Age banding on books? No thanks appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.

April 12, 2015

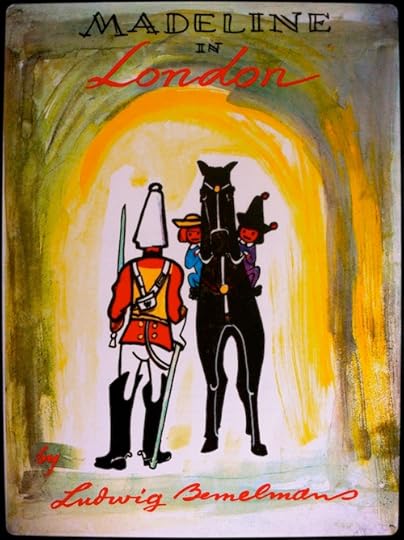

Madeline in London

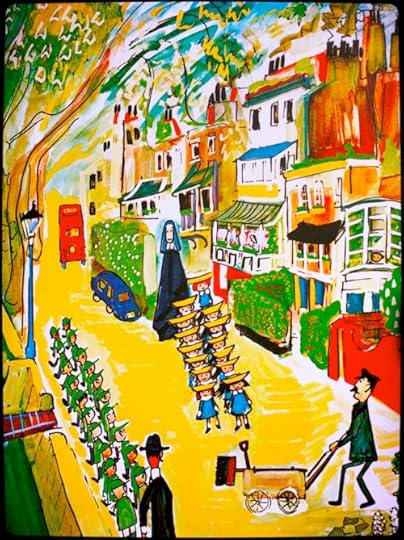

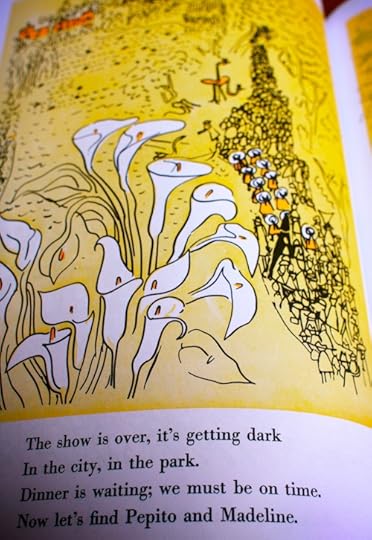

Really, what’s not to love about Madeline? I discovered this book in a charity shop years ago when my kids were still really little and was drawn by the fabulous vintage drawings (Bemelmans published his Madeline books between 1939 and 1961), every colour double-spread page alternating with yellow, black and grey pictures. So I was very happy when I discovered there are a number of Madeline books, for example Madeline and the Gypsies and Madeline’s Rescue and always kept an eye out for them at the local library. Each of the books starts with the same words, In an old house in Paris, that was covered with vines, lived twelve little girls in two straight lines…the smallest one was Madeline.

Madeline is a brave, rambunctious little girl who is cared for, along with the other girls, by a nun named Miss Clavel. Whilst the other eleven little girls do as they are told, Madeline’s rebelliousness always seems to be getting her into fixes, but it’s impossible not to admire her big, open-hearted, adventurous spirit.

In this story, Miss Clavel and the girls go to London to pay a visit to a little boy named Pepito, the son of the Spanish ambassador who used to live next door to them in Paris and has now moved to London and is pining for his friends.

They buy Pepito a horse for his birthday present, but he and Madeline go missing whilst riding the horse, so Miss Clavel and the eleven remaining girls take to the streets of London in hot pursuit of them.

Madeline in London is a celebration of England’s capital city, rendered in beautiful, bold pictures and gently rhyming verse. A Madeline book is a must for a child’s library, and would also make a wonderful gift.

[image error]

Madeline’s creator, Ludwig Bemelmans, who was originally from Austria but settled in the USA. Legend has it that, whilst working at a hotel in Austria, he shot and seriously wounded a waiter following an altercation. Given the choice of reform school and emigration to the US, he chose the latter!

The post Madeline in London appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.

April 4, 2015

Keeping the stories alive

It seems I have a bit of a thing about elderly men. That’s not nearly as dodgy as it sounds. Let me explain. Whilst researching for my first novel, The Poet’s Wife, I was lucky enough to interview a gent in his 90′s by the name of Bob Doyle not long before he died in 2009. Bob was an Irish activist and veteran of the International Brigades as well as the second world war. I remember hobbling to his house in North London (I was on crutches following a bad skiing accident) on a freezing cold day, and we sat in his front room with our breath crystallising before us whilst he told me what inspired him and his friends to leave behind everything they knew to go and fight for another country’s cause. The way he told it, it all made perfect sense. And listening to him talk that afternoon with a passion in no way diminished after seventy years, it was impossible not to ask myself the question, If I was alive in the 1930′s, would I have been brave enough to do the same? (Because yes, many women also went to Spain from around the world). In many ways, Bob was the inspiration for my character Henry in The Poet’s Wife and Bob, too, married a Spanish woman he met whilst in Spain.

Click here to read more about the revolutionary Bob Doyle who rode a motorbike well into his eighties around London and was a vociferous advocate for the legalisation of cannabis, growing it in his London greenhouse.

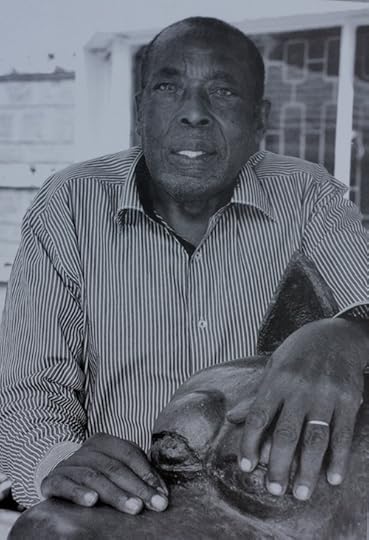

Bob Doyle, 1916-2009

Here in Kenya, working on my second novel, I’ve been to chat to a couple of fascinating men (again, both in their nineties). Major Paddy Deacon has the most astonishing memory and was able to recall names, dates and places quite easily, chiding himself when his memory momentarily lapsed. He has been blind for several years, but this serves to only make him more finely attuned to every sound around him, not missing a single word I said. Paddy came to Kenya with his young family in the early 1950′s to serve in the Kenya Regiment. This was a period of enormous social and political turmoil in colonial Kenya with the Mau Mau guerillas trying to reclaim their land from the wazungu (white people) and punish those Kenyans who remained loyal to the British crown and government. Many of the Mau Mau hid in caves and forests of the Aberdares region and Paddy’s remit was to go into the forest to root them out. He had to employ the undercover tactics of the Mau Mau, going without food for days, sleeping beneath trees and tracking the dense wilderness to discover where these men vanished to.

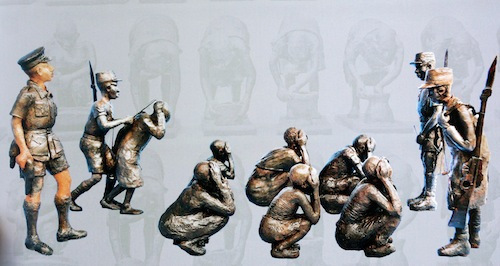

On the other side of this, last week I met Edward Njenga. Edward, from the Kikuyu tribe, does not know how old he is because at the time he was born, the date of birth was not important but rather which circumcision group children fell into. But he knows he is over ninety. Edward was never enlisted into the Mau Mau (unlike thousands of Kikuyu who had to undergo forced oathing and loyalty to the Mau Mau cause), yet despite this he was sent to a detention camp (under the British colonial government) where he remained for two years. The treatment he and his fellow Kikuyu were subjected to there was horrifying, yet Edward incredibly bears no grudge, cheerfully telling me that he ‘regrets nothing’. He was, however, one of the lucky ones. For it was discovered that he had a talent for art and he was taken from the detention camp by the Quakers to work at a youth centre in Nairobi. Fast forward sixty odd years, Edward is one of Kenya’s most successful and well known scupltors, his work fetching thousands of pounds. When I met him in his studio, his hands did not stop for a second, modelling a mother and child. ‘I have a vision,’ he told me ‘and then I just chip away from the clay or wood the parts I don’t need.’ That simple, right? He said he had been blessed because whilst he might be a little deaf (we had a few communication problems!), his eyes had never failed him, allowing him to continue working.

Langata Mau Mau Detention Camp. Edward scuplted this in 1970, nearly 20 years after he was interned in the camp, a testament to what he describes as his ‘photographic memory.’

Another of Edward’s pieces, entitled ‘I love you but’ (1970)

How amazing and humbling to have met these three elderly gentlemen, overflowing with knowledge and wisdom and stories that must not be forgotten. I have another man lined up (again, in his nineties, naturally!), an Indian man whose grandfather was Nairobi’s first shoemaker. He sounds like quite a character who whizzes around Nairobi still at breakneck speed in his car. No doubt you’ll be meeting all these characters again in one way or another in my next book. Watch this space…

The post Keeping the stories alive appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.