Rebecca Stonehill's Blog, page 65

October 2, 2015

Want your kids to be more environmentally aware? Look no further

Ancient native American wisdom shares that humanity’s greatest guide is nature and the means to protect this delicate balance and best serve the needs of the community is through the children. For children, of course, have always represented our future. To this end, a pledge was taken by the Native Americans to their people and their way of life. It reads thus:

No law, no decision, nothing of any kind will be agreed by this council that will harm the children.

The council gathered around a small fire in the centre of their community to make this pledge and it soon became known symbolically as The Children’s Fire. I do not need to spell out the importance of this to our lives today. Unwittingly, we continue to harm our children and their descendants as we harm our environment. What can be done to counter this? A great many things, and I think most of us know where to begin if we choose to be courageous enough to make these changes in our lives. But I’d like to share four wonderful books with you today that can open the eyes of our little eco-warriors, and in turn open our own hearts.

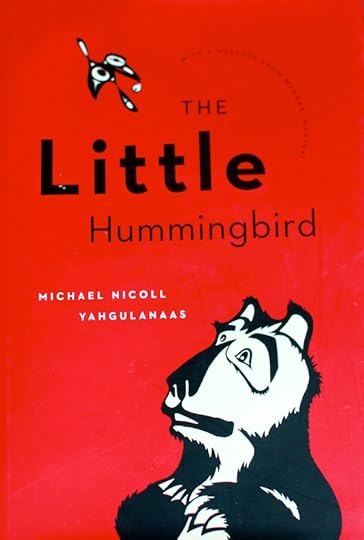

Fittingly, the creator of The Little Hummingbird , Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas, is himself a native Indian from North Columbia. As well as dedicating his book to indigenous people from all around the world, The Little Hummingbird also includes a message from Wangari Maathai (1940-2011), an inspirational environmental activist who founded Kenya’s Green Belt movement and pioneered the planting of millions of trees to counter deforestation.

This simple, elegantly illustrated and sparsely worded fable tells the tale of the great forest that once caught on fire. The animals and birds of the forest were thrown into great panic and turmoil, fleeing from the raging flames as far as they could go. Yet one creature and one alone stayed.

‘Little Hummingbird did not abandon the forest. She flew as fast as she could to the stream. She picked up a single drop of water in her beak. Little Hummingbird flew back and let the water fall onto the ferocious fire.’

The other creatures watched, terrified, as Little Hummingbird flew back and forth, back and forth.

‘Finally, Big Bear said, “Little Hummingbird, what are you doing?” ‘

Her answer?

Including some facts at the back of the book about the amazing abilities of the hummingbird (for example, did you know that they hover in midair by flapping their wings more than fifty times per second?), The Little Hummingbird is a joy from start to finish.

‘One of the greatest lessons I have learned is that all people – young or old, big or small, girl or boy – have power.We can achieve the life we want for ourselves and our families when we pay attention to protecting our environment. We must not wait for others to do it.’

Wangari Maathai

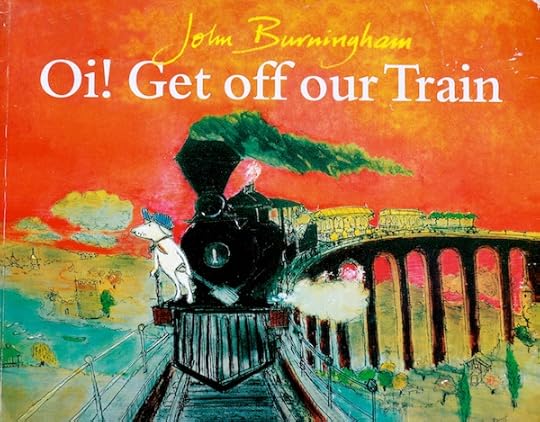

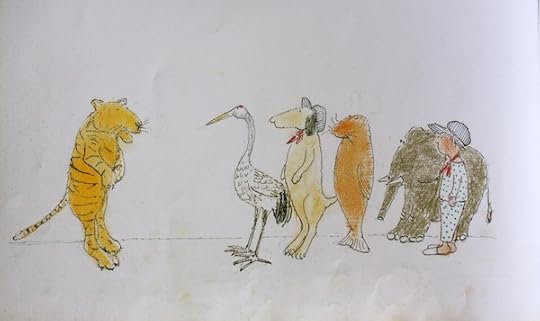

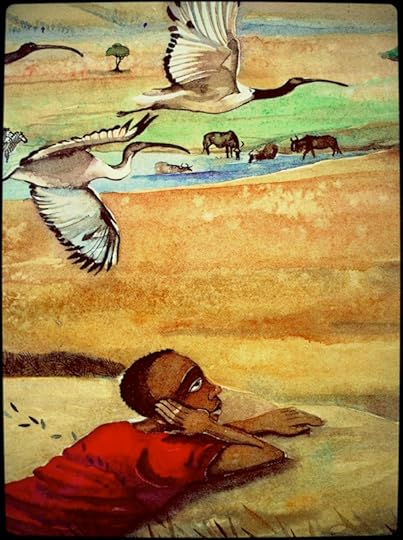

John Burningham’s Oi! Get off our train is a firm favourite amongst my children, especially my five year old. It tells the story of a young boy who goes to sleep one night with his model train set at the end of the bed. Before he knows it, he finds himself as driver of the train, picking up an assortment of creatures one by one on his journey such as an elephant, a crane and a seal. At first, the boy is reluctant to let the animals join him (shouting ‘Oi! Get off our train!), but once he hears of their plights, he relents.

The crane, for example, says ‘I live in the marshes and they are draining the water out of them. I can’t live on dry land and soon there will be none of us left. And the seal pleads ‘If I stay in the sea I won’t have enough to eat because people are making the water very dirty and they are catching too many fish, and soon there will be none of us left.’

So the boy and all his new creature friends, who are facing difficulty at the hands of humans in one way or another, continue along their journey, playing games as they go until the boy concedes he must get back home as he has school in the morning. He wakes safely in his bed, wondering if this was all a dream. But when his mother comes in, she tells him ‘There’s an elephant in the hall, a seal in the bath, a crane in the washing, a tiger on the stairs and a polar bear by the fridge. Is it anything to do with you?’

A modern environmental parable for children, with a gentle wink at the crossover between imagination and reality, Oi! Get off my train will doubtless have the young reader asking questions, wanting to know more.

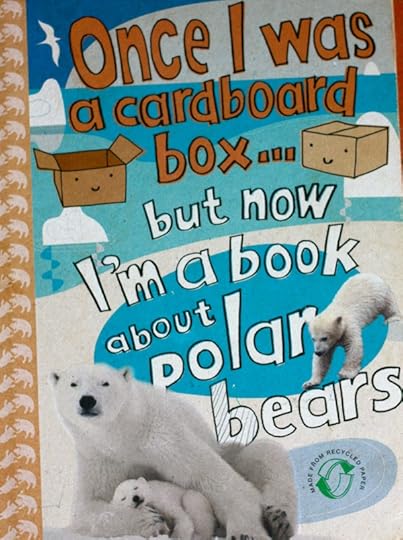

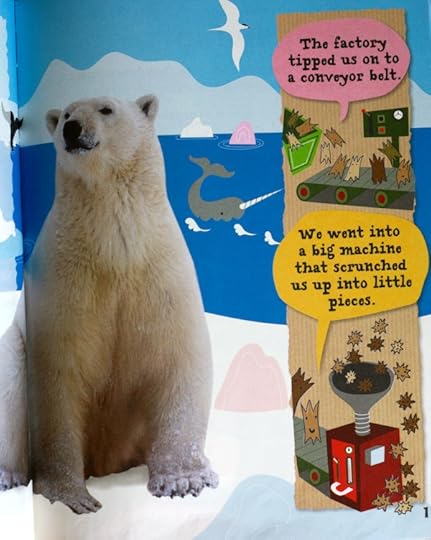

Once I was a cardboard box…but now I’m a book about polar bears is a non-fiction offering from Anton Poitier. Made from recycled paper, this clever book has a dual function: to provide the reader with lots of interesting tidbits of information and pictures about polar bears (e.g. Did you know that cubs are born around november and the mother stays with them in the maternity den for four or five months and during all that time she doesn’t eat, drink or poo!) and also to go through the process of how the book made its transformative journey from a cardboard box .

At the end of each double-page spread, a column is dedicated to this journey, bringing alive the recycling process in a practical, entertaining and easily understandable way. Whilst in no way a book explicitly devoted to global warming and the dangers faced by these species, right at the back the young reader is introduced to the concept of rising temperatures and melting ice and how, in 2008, the polar bear was officially declared an endangered species. Finally, Once I was a cardboard box readers are encouraged to do what they can to play their role in helping to combat this, with some practical tips on where to start.

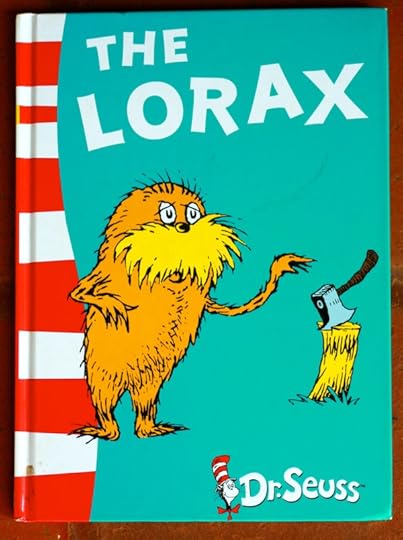

Theodor Geisel, or Dr Seuss as he is far commonly known, needs no introduction. Beloved of generations of children and adults alike, his books are quirky, fun, colourful and inimitable. But underlying many of his works lies something more profound, a deeper moral undercurrent that indeed many great writer’s for children weave into their text. The Lorax is no exception to this. Whilst popularised to an even greater extent by a 2012 movie, the book itself takes the reader through a journey that the film is unable to do: from confusion to joy to anger through to sadness and then, just as one believes all is lost, finishing on a note of profound hope.

The Lorax once lived in a plentiful green land surrounded by Brown Bar-ba-loots, humming-fish, Swomee-Swans and beautiful Truffala Trees, the fruit of which feeds the surrounding creatures. But into this paradisiacal land arrives the Once-ler:

‘But those trees! Those trees! Those Truffala Trees!

All my life I’d been searching for trees such trees as these.

The touch of their tufts was much softer than silk.

And the had the sweet smell of fresh butterfly milk.

I felt a great leaping of joy in my heart.

I knew just what I’d do! I unloaded my cart.’

And so begins the chopping down of the Truffala trees in great numbers in order to use their soft tufts to knit a ‘thneed’ (‘It’s a shirt. It’s a sock. It’s a glove. It’s a hat. But it has other uses. Yes, far beyond that. You can use it for carpets. For pillows! For sheets! Or curtains! Or covers for bicycle seats!’)

The Lorax tries every way he knows how to prevent the Once-ler from continuing in this destructive vein. But people keep buying the thneeds, and where there is demand he must drive the supply.

It isn’t long before there is no more food for the Brown Bar-ba-loots and the Lorax has to sends them off, wishing them luck. And, with a cynical nod in the direction of many a natural-resource devouring corporation, The Once-ler ‘felt sad as I watched them all go. BUT…business is business! And business must grow regardless of crummies in tummies, you know.‘ Eventually, all the creatures are pushed out of their natural habitat until the very last of the Truffula trees is cut down with a ‘sickening smack.’

And just like that, there are ‘No more trees. No more Thneeds. No more work to be done,’ and all the workers drive away under ‘the smoke-smuggered stars’ and the ‘bad-smelling sky.’ So too do all the creatures disappear, as well as the Lorax who vanishes through a hole in the smog.

As we believe all is lost for this once-beautiful land, in true Seuss style, he pulls one last trick out of his bag for this wonderful story. Many years later, the Once-ler throws down something from his tower to a boy who has happened upon this desolate wasteland:

‘It’s a Truffula Seed. It’s the last one of all!

You’re in charge of the last of the Truffula Seeds.

And Truffula Trees are what everyone needs.

Plant a new Truffula. Treat it with care.

Give it clean water. And feed it fresh air.

Grow a forest. Protect it from axes that hack.

Then the Lorax and all of his friends may come back.’

If you don’t already own a copy of The Lorax, buy it without delay. This life-affirming, call-to-action book is a timeless parable of how we, like the Lorax, must play our roles in protecting our planet.

The post Want your kids to be more environmentally aware? Look no further appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.

Four great books for little eco-warriors

Ancient native American wisdom shares that humanity’s greatest guide is nature and the means to protect this delicate balance and best serve the needs of the community is through the children. For children, of course, have always represented our future. To this end, a pledge was taken by the Native Americans to their people and their way of life. It reads thus:

No law, no decision, nothing of any kind will be agreed by this council that will harm the children.

The council gathered around a small fire in the centre of their community to make this pledge and it soon became known symbolically as The Children’s Fire. I do not need to spell out the importance of this to our lives today. Unwittingly, we continue to harm our children and their descendants as we harm our environment. What can be done to counter this? A great many things, and I think most of us know where to begin if we choose to be courageous enough to make these changes in our lives. But I’d like to share four wonderful books with you today that can open the eyes of our little eco-warriors, and in turn open our own hearts.

Fittingly, the creator of The Little Hummingbird , Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas, is himself a native Indian from North Columbia. As well as dedicating his book to indigenous people from all around the world, The Little Hummingbird also includes a message from Wangari Maathai (1940-2011), an inspirational environmental activist who founded Kenya’s Green Belt movement and pioneered the planting of millions of trees to counter deforestation.

This simple, elegantly illustrated and sparsely worded fable tells the tale of the great forest that once caught on fire. The animals and birds of the forest were thrown into great panic and turmoil, fleeing from the raging flames as far as they could go. Yet one creature and one alone stayed.

‘Little Hummingbird did not abandon the forest. She flew as fast as she could to the stream. She picked up a single drop of water in her beak. Little Hummingbird flew back and let the water fall onto the ferocious fire.’

The other creatures watched, terrified, as Little Hummingbird flew back and forth, back and forth.

‘Finally, Big Bear said, “Little Hummingbird, what are you doing?” ‘

Her answer?

Including some facts at the back of the book about the amazing abilities of the hummingbird (for example, did you know that they hover in midair by flapping their wings more than fifty times per second?), The Little Hummingbird is a joy from start to finish.

‘One of the greatest lessons I have learned is that all people – young or old, big or small, girl or boy – have power.We can achieve the life we want for ourselves and our families when we pay attention to protecting our environment. We must not wait for others to do it.’

Wangari Maathai

John Burningham’s Oi! Get off our train is a firm favourite amongst my children, especially my five year old. It tells the story of a young boy who goes to sleep one night with his model train set at the end of the bed. Before he knows it, he finds himself as driver of the train, picking up an assortment of creatures one by one on his journey such as an elephant, a crane and a seal. At first, the boy is reluctant to let the animals join him (shouting ‘Oi! Get off our train!), but once he hears of their plights, he relents.

The crane, for example, says ‘I live in the marshes and they are draining the water out of them. I can’t live on dry land and soon there will be none of us left. And the seal pleads ‘If I stay in the sea I won’t have enough to eat because people are making the water very dirty and they are catching too many fish, and soon there will be none of us left.’

So the boy and all his new creature friends, who are facing difficulty at the hands of humans in one way or another, continue along their journey, playing games as they go until the boy concedes he must get back home as he has school in the morning. He wakes safely in his bed, wondering if this was all a dream. But when his mother comes in, she tells him ‘There’s an elephant in the hall, a seal in the bath, a crane in the washing, a tiger on the stairs and a polar bear by the fridge. Is it anything to do with you?’

A modern environmental parable for children, with a gentle wink at the crossover between imagination and reality, Oi! Get off my train will doubtless have the young reader asking questions, wanting to know more.

Once I was a cardboard box…but now I’m a book about polar bears is a non-fiction offering from Anton Poitier. Made from recycled paper, this clever book has a dual function: to provide the reader with lots of interesting tidbits of information and pictures about polar bears (e.g. Did you know that cubs are born around november and the mother stays with them in the maternity den for four or five months and during all that time she doesn’t eat, drink or poo!) and also to go through the process of how the book made its transformative journey from a cardboard box .

At the end of each double-page spread, a column is dedicated to this journey, bringing alive the recycling process in a practical, entertaining and easily understandable way. Whilst in no way a book explicitly devoted to global warming and the dangers faced by these species, right at the back the young reader is introduced to the concept of rising temperatures and melting ice and how, in 2008, the polar bear was officially declared an endangered species. Finally, Once I was a cardboard box readers are encouraged to do what they can to play their role in helping to combat this, with some practical tips on where to start.

Theodor Geisel, or Dr Seuss as he is far commonly known, needs no introduction. Beloved of generations of children and adults alike, his books are quirky, fun, colourful and inimitable. But underlying many of his works lies something more profound, a deeper moral undercurrent that indeed many great writer’s for children weave into their text. The Lorax is no exception to this. Whilst popularised to an even greater extent by a 2012 movie, the book itself takes the reader through a journey that the film is unable to do: from confusion to joy to anger through to sadness and then, just as one believes all is lost, finishing on a note of profound hope.

The Lorax once lived in a plentiful green land surrounded by Brown Bar-ba-loots, humming-fish, Swomee-Swans and beautiful Truffala Trees, the fruit of which feeds the surrounding creatures. But into this paradisiacal land arrives the Once-ler:

‘But those trees! Those trees! Those Truffala Trees!

All my life I’d been searching for trees such trees as these.

The touch of their tufts was much softer than silk.

And the had the sweet smell of fresh butterfly milk.

I felt a great leaping of joy in my heart.

I knew just what I’d do! I unloaded my cart.’

And so begins the chopping down of the Truffala trees in great numbers in order to use their soft tufts to knit a ‘thneed’ (‘It’s a shirt. It’s a sock. It’s a glove. It’s a hat. But it has other uses. Yes, far beyond that. You can use it for carpets. For pillows! For sheets! Or curtains! Or covers for bicycle seats!’)

The Lorax tries every way he knows how to prevent the Once-ler from continuing in this destructive vein. But people keep buying the thneeds, and where there is demand he must drive the supply.

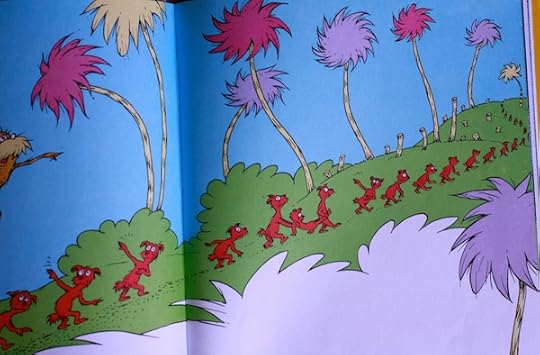

It isn’t long before there is no more food for the Brown Bar-ba-loots and the Lorax has to sends them off, wishing them luck. And, with a cynical nod in the direction of many a natural-resource devouring corporation, The Once-ler ‘felt sad as I watched them all go. BUT…business is business! And business must grow regardless of crummies in tummies, you know.‘ Eventually, all the creatures are pushed out of their natural habitat until the very last of the Truffula trees is cut down with a ‘sickening smack.’

And just like that, there are ‘No more trees. No more Thneeds. No more work to be done,’ and all the workers drive away under ‘the smoke-smuggered stars’ and the ‘bad-smelling sky.’ So too do all the creatures disappear, as well as the Lorax who vanishes through a hole in the smog.

As we believe all is lost for this once-beautiful land, in true Seuss style, he pulls one last trick out of his bag for this wonderful story. Many years later, the Once-ler throws down something from his tower to a boy who has happened upon this desolate wasteland:

‘It’s a Truffula Seed. It’s the last one of all!

You’re in charge of the last of the Truffula Seeds.

And Truffula Trees are what everyone needs.

Plant a new Truffula. Treat it with care.

Give it clean water. And feed it fresh air.

Grow a forest. Protect it from axes that hack.

Then the Lorax and all of his friends may come back.’

If you don’t already own a copy of The Lorax, buy it without delay. This life-affirming, call-to-action book is a timeless parable of how we, like the Lorax, must play our roles in protecting our planet.

The post Four great books for little eco-warriors appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.

September 3, 2015

What is the one thing that we all owe to ourselves and to humanity?

This is not a blog about writing. It is not a children’s book review and it is not offering up tips about how to engage kids with creative writing and poetry. It is a blog about what we can possibly do, how we as humans can feel any less impotent in the face of all this suffering that we know goes on around the world.

Today, it is the image of the bodies of three year old Aylan Kurdi and his five year old brother Galip washing up on a beach in Turkey, Kurdish refugees fleeing the conflict in Syria in a desperate attempt to seek asylum in Canada. But yesterday it was a different image and a different conflict. There will always be images and human stories behind them that will haunt us. We sit in front of our computer and TV screens and we download this gruesome pictures into our minds, filing them into a box we push back as far as we can. And then we continue with our lives because what, really, can we do?

It’s a good question. More than that, it’s an age-old question and one that we in the West have the privilege to dip in and out of. We can buy The Big Issue, arrange a monthly direct debit to Friends of the Earth and practice some armchair activism by emailing our MP’s about the closure of the local library, then pat ourselves on the back for doing something. But it is enough? What can ever be ‘enough’?

Hey, I’m not judging. These things are all good and are sure as hell better then doing nothing at all. But let’s face it, when children come into the picture, this tugs at the heart strings more than anything else (think of BBC’s Children in Need which raises more millions in a single night for kids than any other charity), which is why I am probably writing this today, as those images of Aylan and Galip in the past couple of days have been unavoidable.

I don’t pretend to know the answer. Suffering and the cause of it is so multi-layered and is never, ever black and white. I remember as a child on holiday with my parents in San Francisco witnessing first hand the huge number of people living on the streets. My brother and sister and I wanted to help and we would save them our breakfasts from our hotel and then give them to the homeless people, feeling at least we were ‘doing’ something; helping in some way. And yet, so many of them scoffed at us, pushing the food away. They didn’t want food. They wanted money. This was my first lesson, as a child, in the complexities of suffering. That there is no easy answer.

But here is my suggestion to anyone reading this. It is a tiny, miniscule little drop in a vast sea of suffering. But it is something.

Volunteer.

Let me clarify. What are you interested in? What are you inspired by? What makes you tick or gets that heart beating just a little faster? If you want to save Britain’s dwindling number of hedgerows, don’t just think about it, join a local environmental group and do something about it. If you love books, ask as your local library about reading to vulnerable or lonely or elderly people. If you like horse riding, join a riding for the disabled group.

I love writing so I volunteer at a school in Nairobi with kids who have no access to anything vaguely creative. Shit, the last thing I want is to sound virtuous as it is such a small thing. Seriously, we cannot save the whole world. It is far, far too broken. But we can do something, something small. So let’s let something good come out of these horrific images we are confronted with day in, day out. Let’s make a difference to someone else’s life. Don’t simply continue to think about it. Do it. Please.

The post What is the one thing that we all owe to ourselves and to humanity? appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.

This is not a blog about writing. This is a call to action.

This is not a blog about writing. It is not a children’s book review and it is not offering up tips about how to engage kids with creative writing and poetry. It is a blog about what we can possibly do, how we as humans can feel any less impotent in the face of all this suffering that we know goes on around the world.

Today, it is the image of the bodies of three year old Aylan Kurdi and his five year old brother Galip washing up on a beach in Turkey, Kurdish refugees fleeing the conflict in Syria in a desperate attempt to seek asylum in Canada. But yesterday it was a different image and a different conflict. There will always be images and human stories behind them that will haunt us. We sit in front of our computer and TV screens and we download this gruesome pictures into our minds, filing them into a box we push back as far as we can. And then we continue with our lives because what, really, can we do?

It’s a good question. More than that, it’s an age-old question and one that we in the West have the privilege to dip in and out of. We can buy The Big Issue, arrange a monthly direct debit to Friends of the Earth and practice some armchair activism by emailing our MP’s about the closure of the local library, then pat ourselves on the back for doing something. But it is enough? What can ever be ‘enough’?

Hey, I’m not judging. These things are all good and are sure as hell better then doing nothing at all. But let’s face it, when children come into the picture, this tugs at the heart strings more than anything else (think of BBC’s Children in Need which raises more millions in a single night for kids than any other charity), which is why I am probably writing this today, as those images of Aylan and Galip in the past couple of days have been unavoidable.

I don’t pretend to know the answer. Suffering and the cause of it is so multi-layered and is never, ever black and white. I remember as a child on holiday with my parents in San Francisco witnessing first hand the huge number of people living on the streets. My brother and sister and I wanted to help and we would save them our breakfasts from our hotel and then give them to the homeless people, feeling at least we were ‘doing’ something; helping in some way. And yet, so many of them scoffed at us, pushing the food away. They didn’t want food. They wanted money. This was my first lesson, as a child, in the complexities of suffering. That there is no easy answer.

But here is my suggestion to anyone reading this. It is a tiny, miniscule little drop in a vast sea of suffering. But it is something.

Volunteer.

Let me clarify. What are you interested in? What are you inspired by? What makes you tick or gets that heart beating just a little faster? If you want to save Britain’s dwindling number of hedgerows, don’t just think about it, join a local environmental group and do something about it. If you love books, ask as your local library about reading to vulnerable or lonely or elderly people. If you like horse riding, join a riding for the disabled group.

I love writing so I volunteer at a school in Nairobi with kids who have no access to anything vaguely creative. Shit, the last thing I want is to sound virtuous as it is such a small thing. Seriously, we cannot save the whole world. It is far, far too broken. But we can do something, something small. So let’s let something good come out of these horrific images we are confronted with day in, day out. Let’s make a difference to someone else’s life. Don’t simply continue to think about it. Do it. Please.

The post This is not a blog about writing. This is a call to action. appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.

August 24, 2015

How can you be a writer during the kids’ school holidays?

‘Mummy, you’ve been working forever. Stop it, now.’

This is my little boy, recently turned five, tugging at my sleeve and trying to force my laptop shut. I explain to him that I really need to do a little more, then I promise I’ll play with him in half an hour.

‘Half an hour?’ he shrieks indignantly. ‘No. That is too. Too, TOO long.’

Oh, the joys of trying to be a writer during the school summer holidays.

I live with my husband and three children in Nairobi, but we’re back in the UK for a couple of months during their holidays. I am in the process of editing my second novel but, as I discovered last summer as well, trying to keep three young children happy whilst frantically attempting to work on a novel is no easy task. This juggling act is, of course, far from exclusive to writers and is an age-old problem for working parents the world over, particularly during those long holidays. For those who work from home, it throws up a whole new set of interesting challenges that need to be approached open-mindedly and creatively. Of course there’s always the option of writing once they’re in bed, but I doubt I’m alone when I say that writing last thing at night doesn’t work for me. The old brain just isn’t in gear.

After my five year old’s latest outburst, it got me thinking. How do you keep kids happy, filling their holiday time with memories, multi-layered fun and experiences whilst trying to sneak off into another room to work and feel like you’re making decent progress on that front too? Ok, I put my hands up here: I am no expert on this subject and many, many times I feel like I’ve made a pig’s ear of the day, achieving neither a decent amount of writing / editing, nor do I have a contented coterie of kids.

But I would like to share a few things I’ve tried both last and this summer which, if you have children around the same age as mine (9,7 & 5) could give you an extra five minutes of writing time or, if they roll with it, considerably longer. Either way, it’s crucial writing time so it’s worth a try, right? (Of course there’s always the TV, that perennial childminder, but there’s only so much TV a kid can watch.)

1) Get a ball of wool. Any ball of wool. Any colour. Give it to your children and say they have to decorate the sitting room in any way the choose. This is what my lot came up with, a rather lovely spider’s web:

2) Read the part in George’s Marvellous Medicine to your children where he makes the potion. Then get a big pot or jug out and search through your cupboards for all those pots and jars stewing in their own ancient juices that – face it – you’re never going to use and let them give it a great big stir with sticks. (Probably better to do this one outside)

3) Ask the children to lay out an obstacle / assault course in the garden (or, if you don’t have a garden, the sitting room). Provide them with plenty of props such as blankets or sarongs, buckets, balls and bats or rackets, boxes, logs etc etc. At various stages around the course, suggest that the participant has to do a little task such as ten star jumps or chucking balls into a bucket. When they’ve finished making the course (the more elaborate the better for that extra writing time!), YOU have to try it out. Yes, that does mean you may have to be doing squat jumps or crawling through the mud but hey, it’s worth it

4) Is there a storybook all your children particularly love? Ask them to chose between them a story (children’s picture books are best for this as are shorter and more manageable) and devise a play from it. If you only have two children and there are many characters, don’t worry! Add in teddies or just get them to be creative. They’ll know the story really well so even if they’re not reading properly, it doesn’t matter. If you have a dressing up box to accompany this activity, even better. At the end, they can ‘perform’ the story. I love seeing what my children come up with (I must confess I’ve used this on weekend mornings to get an extra half hour in bed, not just for writing time!)

5) Tell your children you want them to prepare lunch for you all with a starter, main course and pudding. They can use anything they find in the cupboards or fridge but cannot use the hobs or oven (Five year old boys and fire? Erm…I think not). Be prepared for some pretty (how shall I put this politely?) unusual flavours but children adore having autonomy in the kitchen and it’s not going to kill you this once if you eat mashed chocolate and apricot on bread and butter for lunch.

Enjoy! And let me know how you get on with any of the above

My three little adventurers on holiday recently in Wales

The post How can you be a writer during the kids’ school holidays? appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.

August 16, 2015

‘The Time of the Lion’ book review-The most lyrical and gentle story ever written about lions

I have long been a fan of the art of Jackie Morris who has illustrated numerous children’s books, including one of my favourite animal books, How the Whale Became, (written by Ted Hughes), short stories about how many animals came into existence.

In the wake of a Minnesota dentist going into hiding following the international outrage over the hunting and killing of iconic Zimbabwean lion, Cecil, there seemed no more apt time to pick up Caroline Pitcher and Jackie Morris’s children’s book, The Time of the Lion. This tender tale follows the story of a young boy, Joseph, who lies in bed at night and hears the roaring of a lion and, though his father tells him it is not yet time for him to meet the creature, curiosity overcomes him and he runs out to the plains.

‘Then a roar thunderclapped across the wide savannah and Joseph saw the sun racing towards him. Its great head streamed with gold. It sprang on paws as big as drums, and its amber eyes glittered so that Joseph feared they’d burn him up there and then.’

Despite the initial fear Joseph feels, a friendship is born between the two of them. They play together (along with the lioness and their cubs) nap together and, ‘…when they woke, the heat of the day shimmered at the edge of the savannah.’ The lion and the boy also talk and, in one particularly prescient conversation bearing in mind the sickening fate of Cecil, the lion tells Joseph that ‘Danger is not always where you think. There are hungry hyenas and lean leopards, rampaging elephants and easy-running cheetahs.’ ‘And lions,’ laughed Joseph. ‘And most of all, men,’ growled the Lion.’

But one day, the fragile balance of their friendship is tested to the core. For the traders come to this land (though a country is never mentioned, I like to think of it as being Kenya) wanting to buy goods from Joseph’s father for the tourists. ‘And,’ they whispered, ‘we pay VERY well for lion cubs. The smaller, the better.’ Joseph can only watch in horror as the traders set out across the savannah, followed by his father who he believes to have betrayed the lion and the cubs when he is unable to find them later in the day, ‘…and he wept for all the lions in the world.’

When the traders make their final deal, Joseph hides his face in shame and runs into the night. ‘He waited. No ROAR. No sun. No Lion. Nothing.’ Returning to his village, bereft, he discovers that his father had also tricked the traders in order to keep the lions safe, hiding the cubs in large pottery urns in his market stall and urging the traders to buy the smaller pots of superior quality. When the Lion reappears before Joseph, his father turns to the creature and speaks:

‘‘Lion, when I was a boy, I was your father’s friend, and I spent my noon-times with him. The Time of the Lion is more precious than gold.’

And finally Joseph understands, that his father was once a young boy, just like himself, who had also learned from the lions.

As an aside and a teaser for the novel I’m currently writing, I have also been exploring the hunting of wild animals in Kenya (previously known as British East Africa) by early colonists. One of my characters, Jeremy Lawrence, entrenched in the mores of Africa’s colonial past, is (like a great many of his contemporaries) a prolific hunter. He has the heads and skins of his ‘trophies’ displayed in his primitive bungalow in Nairobi and, whilst I recoiled against writing this, a pivotal scene in my novel revolves around the protagonist’s fulfilment of her own desires whilst her husband, Jeremy Lawrence, seeks out the creature that he lusts after above all else: the lion. I had to try and get into the head of a hunter (no easy task, believe you me) and, in great detail, chart the staking out of the lion (or lioness in this case) through to the moment of her death. As I said, it really wasn’t easy to write this.

But somehow, it feels like the time of the lion right now, and if our children and grandchildren are to continue with the knowledge that lions roam in the wilds, and not just in zoos, we each have a role to play; to be mindful of the intricate interdependence of our planet’s fragile ecosytems that support both man and beast. The Time of the Lion can help our children to take one small but vital step towards this.

Cecil

The post ‘The Time of the Lion’ book review-The most lyrical and gentle story ever written about lions appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.

Book Review: The Time of the Lion

I have long been a fan of the art of Jackie Morris who has illustrated numerous children’s books, including one of my favourite animal books, How the Whale Became, (written by Ted Hughes), short stories about how many animals came into existence.

In the wake of a Minnesota dentist going into hiding following the international outrage over the hunting and killing of iconic Zimbabwean lion, Cecil, there seemed no more apt time to pick up Caroline Pitcher and Jackie Morris’s children’s book, The Time of the Lion. This tender tale follows the story of a young boy, Joseph, who lies in bed at night and hears the roaring of a lion and, though his father tells him it is not yet time for him to meet the creature, curiosity overcomes him and he runs out to the plains.

‘Then a roar thunderclapped across the wide savannah and Joseph saw the sun racing towards him. Its great head streamed with gold. It sprang on paws as big as drums, and its amber eyes glittered so that Joseph feared they’d burn him up there and then.’

Despite the initial fear Joseph feels, a friendship is born between the two of them. They play together (along with the lioness and their cubs) nap together and, ‘…when they woke, the heat of the day shimmered at the edge of the savannah.’ The lion and the boy also talk and, in one particularly prescient conversation bearing in mind the sickening fate of Cecil, the lion tells Joseph that ‘Danger is not always where you think. There are hungry hyenas and lean leopards, rampaging elephants and easy-running cheetahs.’ ‘And lions,’ laughed Joseph. ‘And most of all, men,’ growled the Lion.’

But one day, the fragile balance of their friendship is tested to the core. For the traders come to this land (though a country is never mentioned, I like to think of it as being Kenya) wanting to buy goods from Joseph’s father for the tourists. ‘And,’ they whispered, ‘we pay VERY well for lion cubs. The smaller, the better.’ Joseph can only watch in horror as the traders set out across the savannah, followed by his father who he believes to have betrayed the lion and the cubs when he is unable to find them later in the day, ‘…and he wept for all the lions in the world.’

When the traders make their final deal, Joseph hides his face in shame and runs into the night. ‘He waited. No ROAR. No sun. No Lion. Nothing.’ Returning to his village, bereft, he discovers that his father had also tricked the traders in order to keep the lions safe, hiding the cubs in large pottery urns in his market stall and urging the traders to buy the smaller pots of superior quality. When the Lion reappears before Joseph, his father turns to the creature and speaks:

‘‘Lion, when I was a boy, I was your father’s friend, and I spent my noon-times with him. The Time of the Lion is more precious than gold.’

And finally Joseph understands, that his father was once a young boy, just like himself, who had also learned from the lions.

As an aside and a teaser for the novel I’m currently writing, I have also been exploring the hunting of wild animals in Kenya (previously known as British East Africa) by early colonists. One of my characters, Jeremy Lawrence, entrenched in the mores of Africa’s colonial past, is (like a great many of his contemporaries) a prolific hunter. He has the heads and skins of his ‘trophies’ displayed in his primitive bungalow in Nairobi and, whilst I recoiled against writing this, a pivotal scene in my novel revolves around the protagonist’s fulfilment of her own desires whilst her husband, Jeremy Lawrence, seeks out the creature that he lusts after above all else: the lion. I had to try and get into the head of a hunter (no easy task, believe you me) and, in great detail, chart the staking out of the lion (or lioness in this case) through to the moment of her death. As I said, it really wasn’t easy to write this.

But somehow, it feels like the time of the lion right now, and if our children and grandchildren are to continue with the knowledge that lions roam in the wilds, and not just in zoos, we each have a role to play; to be mindful of the intricate interdependence of our planet’s fragile ecosytems that support both man and beast. The Time of the Lion can help our children to take one small but vital step towards this.

Cecil

The post Book Review: The Time of the Lion appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.

August 7, 2015

How to get kids writing with jazz

I’m a firm believer in the power of music as a creative force. I’ve written before about using music alongside creative writing in order to see where this takes children on the page, as well as the importance of playlists for my novels. Rhythm and music / Poetry…They’re two sides of the same coin really which is why music can just be the PERFECT tool for creating some unusual writing. Before one of my Magic Pencil sessions, I spent some time searching for a good tune to work with. If you decide to try this with kids, you can use any tune at all, but aim for something without words that has a strong beat and repetitive rhythm (jazz can often be good for this.)

Jazz pianist Mary Lou Williams depicted by Giselle Potter

I chose the opening of Blossom Dearie’s Doop-Doo-De-Doop (See below) up to the part where she sings ‘Why don’t you join the group…’ and here’s a suggestion of how to run this session:

Play the music a number of times up to the speaking part and ask the children to stand in a long line, all facing the same way, and pat the back of the child in front of them with both their hands in the Doop-Doo-De-Doop rhythm until they feel confident with this (some kids will always find this easier than others.) Next, ask the children to clap the rhythm, either alone or together in a big group.

It’s worth splitting the kids into pairs at this point before they have a go on their own to boost their confidence. Ask them to think of words together that fit the rhythm and to write them down. Tell them they are writing a song, and this is also poetry and creative writing and it doesn’t matter if they choose to tell a little story or prefer words independently from one another that slot into the rhythm. Once they’ve had a whirl at this and the pairs have shared their ideas with the group, they’ll be ready to have a go on their own.

You will be amazed what they come up with. This is poetry and song-writing and creative writing all rolled into one and children (and adults!) will love it. Speaking of which, I’m not going to include any of the pieces the kids in my group wrote, as I’d love you to have a go at this yourself. Just click on the link below, listen to the opening sequence up to the words and get your ideas down. It’s really fun, I promise! Tell me what you come up with

The post How to get kids writing with jazz appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.

July 31, 2015

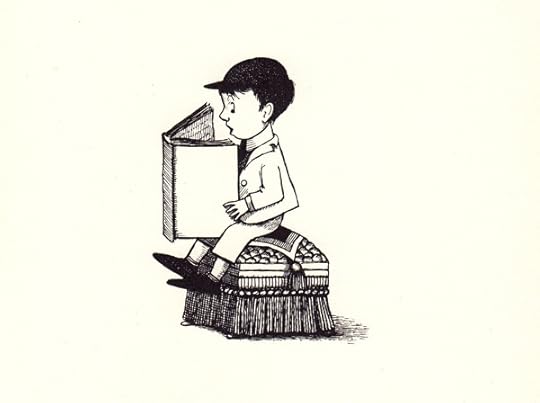

Why as parents and teachers we must all read aloud to older children

‘If speaking is silver, then listening is gold.’

Turkish Proverb

We all know about the benefits of reading to young children, even from birth. It’s been drilled into us as parents and teachers and carers to such an extent you’d be hard pressed to find a young child in the developing world who is never read to. But how about reading to older children?

I started to think about this a while back when my eldest child decided at the age of seven that she didn’t want to be read to anymore because she enjoyed reading on her own so much. I accepted this fairly unquestioningly; it felt a little strange to be breaking that tie (and evening tradition) between us but was, I surmised, one of those natural things that come about as our children grow up and become more independent.

Oliver Jeffers

I let this continue and she devoured book after book on her own, and I was happy with that and glad that she seemed to love books and reading so much. But then recently, a friend came to stay and was surprised to see that I wasn’t reading to my eldest (now aged 9) anymore. I told her it had actually been some time since I’d read to her, to which she replied that I should reconsider that. She commented that my daughter may well be reading at a high level, but what level was she listening at? This friend was read to by her parents until she was fifteen. They read through a great number of the classics as well as a huge number of other books they took it in turns to choose. Now I’m not advocating that we have to read to our kids till they’re in their mid-teens. This is pretty unusual. But her comments got me thinking, and I decided to look into the benefits of reading aloud to older children more deeply.

Maurice Sendak

Apart from the fairly obvious advantages of maintaining that special, tactile bond between parents and children and being able to talk about the books and the issues they throw up during and after reading, it turns out that a number of studies have been carried out on why we should keep reading to children even as they become more independent readers. It may sound like an obvious statement, but one that shouldn’t be overlooked: Children listen on an entirely different level to how they read. And actually, let’s face it, truly active listening shouldn’t be scoffed at: it is hard. Which is why, it turns out, it’s a really good idea to help children with this. And one good way we can do this is by reading aloud to them.

We can read the kind of books that our children wouldn’t necessarily read themselves, and often these books can be ‘targeted’ at a higher age group (though I’m not a fan of age-banding for kids) and so can motivate them to keep reading more challenging material. It really doesn’t matter at all if they don’t understand certain words; they can either ask us or will listen to the cadence and flow of the story and take what they need to take from it.

D.B.Johnson

What else? Is it just me or is anyone else guilty of sometimes ‘zoning out’ whilst reading those same books we’ve read over and over again to children? (What’s for dinner? What do I need to do tomorrow?). If we are actively involved in choosing the story, often re-living some of our own childhood books, we can get engaged and excited again in the storytelling. I’ve found that recently I’ve thrown myself much more into the different voices of characters and actively enjoyed telling the stories. It’s helped me to focus more on the words and engage on a different level. Needless to say, if kids experience adults deriving enjoyment from reading books, they are far more likely to be lifelong readers.

I don’t want to start bemoaning the impact of digital media on our children, as I’m not against young people engaging in technology (if used in the right way.) But attention spans, we can’t deny it, are shorter these days and digital media hasn’t helped this. But read an older child a story and you have just two things: the reader’s voice and the listener’s ears. And what does this do? It results in the listener building empathy and images and sparking all kinds of unpredictable questions and interests.

My nine year old wasn’t impressed when I suggested re-instating reading together. But I gently persevered and now it’s become habitual again and she looks forward to it. Not just my eldest, but all three of my kids I am absolutely certain are benefitting in so many ways from reading aloud: they are listening at a level above their personal reading ages so being exposed to richer stories, their vocabulary is growing and so is their ability to question and process some challenging themes.

So come on, dig out and dust off some of those old favourite’s that inspired us as children. Let’s get reading to kids, no matter their age, and be open to how it could just transform us as well.

Jean-Pierre Weill

The post Why as parents and teachers we must all read aloud to older children appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.

Reading aloud to older children

‘If speaking is silver, then listening is gold.’

Turkish Proverb

We all know about the benefits of reading to young children, even from birth. It’s been drilled into us as parents and teachers and carers to such an extent you’d be hard pressed to find a young child in the developing world who is never read to. But how about reading to older children?

I started to think about this a while back when my eldest child decided at the age of seven that she didn’t want to be read to anymore because she enjoyed reading on her own so much. I accepted this fairly unquestioningly; it felt a little strange to be breaking that tie (and evening tradition) between us but was, I surmised, one of those natural things that come about as our children grow up and become more independent.

Oliver Jeffers

I let this continue and she devoured book after book on her own, and I was happy with that and glad that she seemed to love books and reading so much. But then recently, a friend came to stay and was surprised to see that I wasn’t reading to my eldest (now aged 9) anymore. I told her it had actually been some time since I’d read to her, to which she replied that I should reconsider that. She commented that my daughter may well be reading at a high level, but what level was she listening at? This friend was read to by her parents until she was fifteen. They read through a great number of the classics as well as a huge number of other books they took it in turns to choose. Now I’m not advocating that we have to read to our kids till they’re in their mid-teens. This is pretty unusual. But her comments got me thinking, and I decided to look into the benefits of reading aloud to older children more deeply.

Maurice Sendak

Apart from the fairly obvious advantages of maintaining that special, tactile bond between parents and children and being able to talk about the books and the issues they throw up during and after reading, it turns out that a number of studies have been carried out on why we should keep reading to children even as they become more independent readers. It may sound like an obvious statement, but one that shouldn’t be overlooked: Children listen on an entirely different level to how they read. And actually, let’s face it, truly active listening shouldn’t be scoffed at: it is hard. Which is why, it turns out, it’s a really good idea to help children with this. And one good way we can do this is by reading aloud to them.

We can read the kind of books that our children wouldn’t necessarily read themselves, and often these books can be ‘targeted’ at a higher age group (though I’m not a fan of age-banding for kids) and so can motivate them to keep reading more challenging material. It really doesn’t matter at all if they don’t understand certain words; they can either ask us or will listen to the cadence and flow of the story and take what they need to take from it.

D.B.Johnson

What else? Is it just me or is anyone else guilty of sometimes ‘zoning out’ whilst reading those same books we’ve read over and over again to children? (What’s for dinner? What do I need to do tomorrow?). If we are actively involved in choosing the story, often re-living some of our own childhood books, we can get engaged and excited again in the storytelling. I’ve found that recently I’ve thrown myself much more into the different voices of characters and actively enjoyed telling the stories. It’s helped me to focus more on the words and engage on a different level. Needless to say, if kids experience adults deriving enjoyment from reading books, they are far more likely to be lifelong readers.

I don’t want to start bemoaning the impact of digital media on our children, as I’m not against young people engaging in technology (if used in the right way.) But attention spans, we can’t deny it, are shorter these days and digital media hasn’t helped this. But read an older child a story and you have just two things: the reader’s voice and the listener’s ears. And what does this do? It results in the listener building empathy and images and sparking all kinds of unpredictable questions and interests.

My nine year old wasn’t impressed when I suggested re-instating reading together. But I gently persevered and now it’s become habitual again and she looks forward to it. Not just my eldest, but all three of my kids I am absolutely certain are benefitting in so many ways from reading aloud: they are listening at a level above their personal reading ages so being exposed to richer stories, their vocabulary is growing and so is their ability to question and process some challenging themes.

So come on, dig out and dust off some of those old favourite’s that inspired us as children. Let’s get reading to kids, no matter their age, and be open to how it could just transform us as well.

Jean-Pierre Weill

The post Reading aloud to older children appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.