Rebecca Stonehill's Blog, page 61

July 17, 2016

What makes writers write?

Why do writers write? Why do we plunge ourselves into the often icy waters where we can face loneliness, voices in our head that can be both liberating and disconcerting, and even exposure to ridicule? Do we chose to write, or does writing chose us, tumbling after us like a ball of fire until it has engulfed us? Author Milan Kundera once said that The writer’s job is to get to see the world as a question. But are our questions actually answered through the process of writing?

It’s something I’ve always been interested in, so I decided to ask some fellow authors where the motivation comes from to keep putting that metaphorical pen to paper. It’s certainly not for the money, nor the fame. With a hugely saturated market and the average working author earning less than £10,500 a year, there must be another pretty good reason why we do what we do. Let’s take a look at what people had to say about this…

From Enormous Smallness by Kris Di Giacomo

Sue Watson ‘It fulfils that need to become someone else and imagine another person’s life.’

Renita D’Silva ‘…so I can escape into and sculpt a different world.’

Holly Martin ‘Living the life I want to live through my words. I wrote Fairytale Beginnings to live the life that I can’t.’

Louise Jensen ‘I started writing The Sister after becoming disabled as a way to escape chronic pain. I no longer had the freedom I wanted within my body, but I had the freedom in my mind to create whole new worlds and it was utterly liberating.’

Louise Beech ‘When I got lost in creating stories, something in me calmed and was just… right. I was where I was meant to be. My safe place. Where I was happiest.’

Notice a common thread here? It turns out that it’s not just our audience reading to escape, it is also authors themselves through the very process of writing who would like to find themselves in a better, brighter, more hopeful world; a world in which they can fulfil their dreams vicariously through the lives of their characters or escape difficult situations in their own lives. I know that writing became an anchor for me during prolonged bouts of chronic insomnia. I couldn’t do a great deal else effectively, but the act of writing each and every day helped me to still feel and believe that I was a vital cog in our great wheel of humanity.

Whilst for many writers, the process is something they simply must do, ‘a happy addiction’ of sorts (Caroline Mitchell), another response that came up consistently was the need to get the voices and information out of one’s head and onto the page. As Tracey Sinclair describes it, ‘it’s sometimes like downloading information to clear space on a hard drive: I have so many stories and snippets of stories in my head I’d go a bit crazy if I didn’t set them down.’

Catherine Hokin ‘Because the people in my head are often more real than the people around me and their stories want telling.’

Cassandra Parkin ‘The moment when the characters start arguing back and insisting that actually, no, it happened this way, not that way.’

Debbie Rix ‘I have voices in my head that need to get out, dialogue that needs to be written and stories that need to be told.’

Marie Laval ‘I have all these characters, images, settings, plotlines, bits of dialogues swirling in my mind all the time! It’s exhausting and I need to get them out and on the page. It’s like dreaming awake.’

John Bowen ‘It’s the only place I get to pretend to be lots of other people without getting funny looks.’

Wow. Voices in our heads? What is that really all about? A blog for another day, perhaps.

Writers also come to the page to try and clarify things: our existence, the world around us, conflict, emotions, to articulate the grey space that exists between the black and white.

Claire Seeber ‘To work stuff out…life, love, the universe…for hope, for a sheer love of storytelling.

Angela Marsons ‘I want to explore motivations and actions and situations and feelings.’

Isabel Allende, one of my early influencers as a writer, has said ‘Writing, when all is said and done, is an attempt to understand one’s own circumstances and to clarify the confusion of existence.’ This resonates with me perfectly. It never came to pass, but I once had a place to study a human rights masters at university. I still feel this intensely; my desire for everyone to be treated as equals and find myself getting very hot under the collar about certain things: injustice, cruelty, racism, discrimination…when I write I pour a great deal of this anger into my stories. Can resolution be achieved? Possibly, possibly not. But the release I feel is palpable.

There’s also writing the kind of book we want to read. Kerry Fisher says ‘I couldn’t seem to find books that dealt realistically with family life but were also funny,’ so she decided to write her own (and why not?) There is also the sheer, unalloyed joy of knowing that your words have brought levity to a person’s day, as exemplified by Carol Wyer: ‘I am motivated every day at the thought of making someone smile or chuckle.’ I love that. Are there many more potent tonics than humour? I think not.

Why we chose to write; to make that our career or just dip our paint brush into fictional, painted worlds now and again is different for all of us. We all want to find a way to leave a mark on this world, no matter how small. Perhaps for writers, putting words down achieves this permanence for us.

Please do add to the conversation – I’d love to know: Why do you write?

The post What makes writers write? appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.

July 1, 2016

Lena, Me and The Artist

I wrote this short story, Lena, Me and The Artist many years ago. It was my very first attempt at historical fiction and I’ve kept it exactly as I wrote it back in the day when getting anything published was a dream impossible to visualise. I had no idea at that time where this journey with historical fiction would take me. I wrote this piece as a response to the theme in Mslexia magazine (which I still subscribe to – cannot recommend it enough) which was ‘GLOVES’. So here it is – what came from my imagination from that word. (By the way, yes, he was an artist. This will make sense once you have read the story.)

Comments more than welcome – the good, the bad and the ugly!

‘To dear Miss Katharina,’ the letter read, ‘I am much obliged to you for returning my glove to me. I am quite attached to that particular pair and I am, therefore, very grateful for your trouble. If you would care to call at the hotel one afternoon I would like to invite you for tea and thank you in person. I enjoyed meeting you on the train. Yours,’ and then his name in a great, bold flourish.

I never did go and meet him. I was having far too exciting a holiday to barely give him a second thought. But I kept the letter and now it sits hidden at the back of my closet like a dark, stained secret. Nobody knows he ever wrote to me; that is, apart from Lena. But the fact that he’d been less than charming to my friend offended me on her behalf. And so, he left my life as quickly as he’d entered it. Over the years, I’ve found myself playing out two contrasting scenarios in my mind. One is that over tea at his hotel we embark on a lifelong friendship which somehow changes him, broadens his mind. And in the other, I am luring him to the carriage door of the train, opening it and pushing him to a certain death in the gulley below.

The first time I went on a train without my parents was in the summer of my seventeenth year. It was stiflingly hot, that August of 1911, and after I spent many weeks pleading with them, my parents conceded and allowed me to travel with my friend Lena to her family’s summer house at Lake Wörthersee. My parents insisted they see us off at Vienna station, for they were concerned about us travelling alone and Lena’s family were already at the lake. As we wove our way through the crowds and the steam and the heavy cases being passed up to the carriages, I stared up at the excited people leaning from the windows, chattering to the people on the platform.

‘Katharina, here!’

Lena pointed up at our carriage and after my father had safely installed our bags in the compartment and my parents had hugged us goodbye, we collapsed into our seats. Three weeks! Three whole weeks of walks by the lake, bathing, long lunches, reading and drawing. Sketching was the latest thing amongst our circle of friends – we spent hours at the weekend at each others houses draped over an armchair or sitting before a flower in the garden in deep concentration. I must confess that it usually left me feeling frustrated. Lena was the undisputed talent amongst us: she would capture a scene or a person effortlessly whilst for the rest of us it was a great struggle before we could feel anything close to satisfaction.

When the train pulled out of the station, there were only three other people in our carriage. One was an elderly gentleman who fell asleep as soon as he sat down. His bottom jaw fell wide open and he began to snore loudly; great stilted snorts which made Lena and I giggle terribly. The other two were a middle aged couple who looked as though they had quarrelled, for they wasted no time in snapping open their papers and glaring at one another over the top of them in furious silence. A few minutes after we had left, a young man walked to the door of our carriage. He surveyed the scene before him for some time as though examining a painting in great detail then took two long, purposeful strides to the only spare seat. He carried just one small case with him and,

despite the heat, was wearing a heavy dark coat. As he placed his case on the overhead rail, I turned my head slightly towards Lena, who raised an eyebrow at me and grinned. The truth was that we rarely came into contact with young men and the prospect of having some male company (an elderly snorer and middle-aged feuding husband aside) on our two hour journey made our carriage seem…well, more interesting, certainly.

Having sat down, I noticed that the young man had removed his coat but not his gloves. His clothes were surprisingly shabby. I don’t know why this was a surprise exactly; perhaps because his face was rather distinguished. Lena and I busied ourselves in our books, but I could sense that she was trying as hard as I was to give the impression that we were deeply absorbed in our reading. Snatching glances at our travelling companion over the top of my book, I decided he was a difficult man to age. In one sense, he looked no older than Lena and I yet there was something about his look, rather than his face, which made him seem far older.

As though she had read my thoughts, Lena had brought a pencil from her bag and propped her book on the slant of her lap. In the margin, she slowly wrote 25? I suppressed a smile and with my finger traced a downwards line on the palm of my hand. She continued writing numbers until she reached 21 when, at that point, I nodded my head slightly. Lena grinned at me then took up her novel in earnest and was soon lost in its pages.

Lena. She was my closest, dearest friend in the world. We’d known each other since kindergarten and since that time, we had become virtually inseparable. We couldn’t have looked more different: I was slim and very fair with pale blue eyes. Lena on the other hand had black hair and thick, slanting eyebrows framing her dark, almond shaped eyes. I thought she was beautiful and I longed for her luxuriant black waves and the confidence of her stride. Lena, on the other hand, constantly scowled at her reflection until her eyebrows touched in the middle. ‘I wish I had your skin, Katharina’ she would say, staring with disgust at the colour of her darkening face during the summer months. ‘I wish I had yours’, I would respond truthfully as I stroked the golden brown of her arm.

Lena’s family were bohemian – I sometimes envied my friend her freedom; her bright, unusual clothes; her house filled with books and paintings and the interesting people that would often call on them. But spending time with her allowed me to feel as though I was the same. My parents were kind, honest people but they were conservative in both dress and manners, so it was like a dream come true for me when I was allowed to spend those three weeks at Wörthersee.

The elderly man in our compartment had started to murmur in his sleep and Lena looked up with a start, snapping her book shut. The younger gentleman stole a glance at him then looked back directly ahead, right over the top of my head. But within seconds, the old man’s head had begun to droop so that it lolled on our companion’s shoulder. With distaste, he tried to shift over in his seat, but the carriage was cramped and in doing so, the old man seemed to get in to a more comfortable position and began snoring again. We watched in curiosity as the young man took the elderly gentleman’s head between his gloved hands and gently laid it on the other side, against the compartment wall. Then, very slowly and precisely, he pulled his gloved fingers one by one until they were loosened from his hands, took them off and then hit then sharply together, as though to expel any dust or undesirable dirt that this recent exchange had made his precious gloves come into contact with. He then laid them in his lap and I stared at them. They were fine, hand sewn leather gloves and I found myself wondering how much their owner must have paid for them.

Looking up, I realised that he was staring straight at me. I felt myself flushing and dropped my nose into my book.

‘Excuse me,’ he said in an even, surprisingly strong voice. I looked up slowly and peered over the top of my book. I could feel a very gentle pressure against my left foot where Lena was nudging me. ‘Excuse me,’ he repeated. ‘May I ask what you are reading?’

I felt my whole face being engulfed in what felt like violent flames and yet again, cursed the fact that I did not possess my friend’s darker complexion. ‘Reading? Wh…what am I reading? It’s…’ Flustered, I snapped the book shut and turned it round to face him. ‘It’s a book about Louise – ’

‘Louise Breslau. Yes, I thought I recognised the cover. Do you admire her work?’

I glanced hurriedly at Lena, hoping that she would help me out. After all, it was she that had introduced me to this German artist whose style we had recently being trying to imitate. But Lena remained silent.

‘Do I admire her work?’ Oh, why on earth was I repeating every question he asked me. ‘Yes. Yes indeed, very much.’

He nodded politely at me and I noticed that the elderly man had woken up and was listening to our conversation with one glassy eye wide open. There was silence for several moments and I willed Lena to say something. She was a far better conversationalist than I. She was so accustomed to speaking to complete strangers and I was therefore puzzled and a little annoyed that she wasn’t coming to my rescue.

‘She is a reasonably talented painter,’ he said. ‘But I’ve never cared much for oils.’

‘Do you paint?’ suddenly asked Lena, without a hint of timidity in her voice, and I breathed an inward sigh of relief.

‘Yes,’ he replied. He looked only quickly at my friend and was now smoothing out each finger of one of his gloves with great precision. ‘I am an artist.’

I felt my heart flutter beneath my ribcage and wondered if our travelling companion were a famous painter. Oh, how I longed to freeze time so I could discuss it with Lena!

‘How wonderful!’ enthused Lena. ‘We are artists too!’

The elderly man had gone back to sleep but the warring couple were gazing at us disapprovingly. Lena lent over to the young man and offered him her hand.

‘I am Lena Birnbaum and this is Katharina Kaull.’

He shook Lena’s hand, but I noticed that it lacked any warmth. I extended my own hand and he shook it heartily, looking me directly in the eye which made me feel excited and uncomfortable at the same time.

‘Are you going on a vacation to paint?’ Lena continued. Sometimes I marvelled at her confidence.

‘Yes,’ he replied, but I noticed that he was looking straight at me. ‘I am going to Lake Wörthersee for inspiration. I shall be staying at the Hotel Geblergasse; I’m not sure if you know it. It’s right on the lake. And you? Where are you going?’

I couldn’t understand why he seemed reluctant to include Lena in the conversation and I shifted uneasily in my seat. I glanced beside me and saw that my friend’s forehead had furrowed slightly. ‘We are also going to Wörthersee,’ I said quietly.

‘And will you spend some time painting there?’ he asked. I could feel his eyes boring into me, even though I had dropped my gaze into my lap. I no longer wanted to talk to him and I felt myself reddening. Lena had picked up her novel once more and was leaning her head against the carriage window. I nodded gently and stole a glance up at the young man. He was still staring at me in a way that I had never seen anyone look at me before. One of his eyebrows were raised and he seemed to be appraising me in a way that did not suggest lust or even admiration, but deep, intense interest as though I were a fascinating specimen. I quickly looked down again and placed my hand on my book, hoping that he would sense my discomfort.

‘I’d like to see some of your paintings if you’d allow me, Katharina.’ His use of my name made me smart. Somehow it felt inappropriate and far too intimate.

I looked up at him. ‘Perhaps sometime,’ I opened my book again, signaling the end of the conversation.

Lena and I did not talk whilst the young man remained on the train with us. She looked deeply engrossed in her novel whilst I only feigned interest to avoid having to raise my head. My friend seemed genuinely unworried by our recent brief exchange with our traveling companion whereas I felt intensely uncomfortable. I couldn’t understand it – this man was an artist and surely our mutual interest in painting would have endeared both of us to him. Yet he would only look at me.

At the station before Wörthersee, he jumped up from his seat and gathered his belongings together. I watched him as he scribbled his name on a piece of paper and just before he left he stood close to me.

‘I have to get off here to visit somebody, but I’ll be in Wörthersee by this evening.’ I nodded without the least idea of how to respond, or even if he expected me to respond. ‘I’ve written down my name and hotel name. Please do drop by, Katharina.’

I was reluctant to take the paper from his hand but was keen for him to leave so I quickly did so. Before he left the carriage, he tipped his cap from his head, and was gone. Looking beside me at Lena, she had doubled over with laughter and I prodded her in the ribs.

‘Who has an admirer then? Please do drop by, Katharina,’ she mimicked.

‘Oh, be quiet Lena. He was detestable.’

‘Well, he was clearly smitten by you, my dear.’ Lena returned the disapproving glare of the steely-faced couple and stretched out in her seat like a cat. ‘Surely we must be there soon. Oh – !’

She lent forward and scooped up one of the young man’s gloves from beneath the seat.

‘Let’s throw it out of the window,’ I suggested solemnly.

‘Oh no, I think we should keep it and frame it. You never know, he may be a famous artist one day!’

‘Famous artist? I doubt that somehow.’ I suddenly felt a little unkind and added ‘I suppose I have the name of his hotel. I could always send it back to him.’

‘Or take it in person?’ Lena teased.

‘No. Most definitely not.’

Lena stretched out once again then looked at me and smiled. Lena. My dearest, closest friend in the world. She was only forty-nine when she died. Mother of four; wife; daughter; friend. And over twenty years on, I still miss her, each and every day. All I can hope is that her death wasn’t too lonely, or too painful. And although I refuse to allow myself to dwell on it for the pain I know it will cause me, somehow I doubt this to be so. But this journey, unlike that other train that years later would lead her to her death, was a happy one. Full of summer promise and blissful ignorance. As Lena took up her novel again, I unfolded the paper and read the young man’s precise lettering ‘Adolf Hitler – Hotel Geblergasse.’ No, sadly he was not a famous artist, just a struggling one, like the hundreds of others in Vienna.

I heaved a deep sigh of content. Finally, I could relax. And I was to spend three whole weeks with my dear Lena. I closed my eyes, placed my head against her shoulder and listened to the gentle chug as the train pulled its way towards the lake.

The post Lena, Me and The Artist appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.

June 26, 2016

Why engaging in poetry is a way into writing for kids

Ask a child to write a poem or ask a child to write a story. Which is less daunting?

A story, on the whole, needs a beginning, middle and end. But a poem? It can be pages long. Or it can just be a few words. That’s the beauty of poetry, the complete lack of prescriptiveness, the freedom and space to run amok in any direction you please, simply capturing the essence of something. You can chuck out grammar, punctuation, invent words, write vertically or in the shape of what you are writing about. NO RULES. Liberating, right?

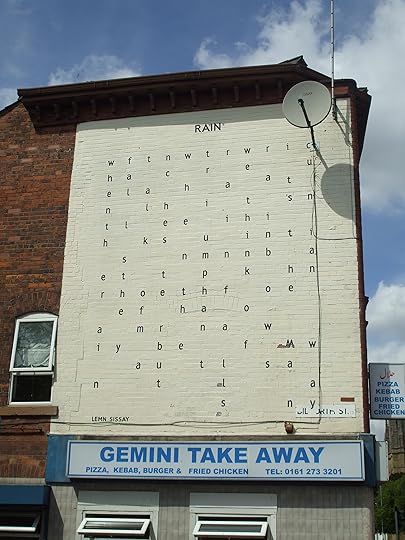

Take a look at fabulous poet Lemn Sissay‘s ‘Rain’ on the wall of a takeaway building in Manchester:

And this is a poem that a child from my creative writing after school club, Magic Pencil, wrote about ice cream:

Poem and picture by Nifa

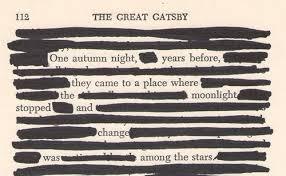

Pick up an old, moth-eaten book at a car boot sale and do this to it:

Poetry is essentially a group of words assembled in any form or style the writer choses. Having run creative writing sessions for children for the past three years, it has become clear that, passionate as I am about prose and enabling children to experiment in this form, the most effective springboard into writing creatively is through poetry.

Where to start?

Read poetry to your children, even when they’re babies. Especially when they’re babies. In the bath. As they’re falling asleep. Make it up as you walk through the woods, playing with the way these sounds feel in your mouth and letting the rhythm of your steps carry your words.

Stress that there are no rules in writing poetry. Make sure you have a selection of books on hand to share with your children that show poetry in all shapes and forms. It’s particularly important to find bellyache laugh-out-loud poetry (try Michael Rosen for starters) as when all is said and done, children need to experience on a visceral level that poetry can be relevant and fun.

Obviously there are no shortage of books to chose from, but I’d like to share the ones we enjoy in my family:

The Puffin Book of Fantastic First Poems

[image error]

This is good for young kids. It would make a fantastic birthday present for little ones and is filled with fun illustrations and work from sixty popular poets.

The Oxford Treasury of Children’s Poems

[image error]

Beautifully illustrated, this has poems to appeal to children of all ages not to mention adults.

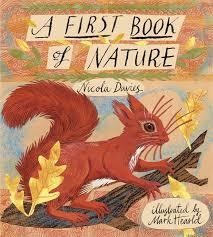

This is not actually a poetry book but a gorgeous celebration of nature. However, I wanted to include it here because of the lyricism and poetic flow of the words that accompany Mark Hearld’s illustrations.

The Walker Book of Poetry for Children

[image error]

Although now out of print, second hand copies of this book are available. One of the things I love about this book is the brilliant index of themes, so you can find a poem for any occasion. Illustrated by Arnold Lobel, it has poems ranging from classics by Lewis Carroll to the quirky verses of Shel Silverstein.

[image error]

Irreverent and raucous, beloved author Roald Dahl retells six well known stories with wicked, memorable twists.

The more poetry (or stories, of course) we read to children, the greater a feel they will have for words as they get older. Author Philip Pullman went as far as to say ‘Children need art and stories and poems and music as much as they need love and food and fresh air and play.’

But if you want to get kids writing, I would go with poetry all the way (particularly if they are reluctant writers). The words that have poured from children during my creative writing session in poetry form continue to amaze and inspire me all the time. That quiet child who sits in the corner not talking to anyone? There is a poem locked up inside them, waiting to get out. That noisy child who cannot sit still or be silent for a moment? Poetry is a way to still their mind, to be present to the page and their own energies.

I believe that people in this world talk too much and listen too little. Once we open up the floodgates of poetry for the children in our lives, there will be no stopping them. Sure, go on to writing stories. But start with poems. You won’t regret it.

The post Why engaging in poetry is a way into writing for kids appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.

June 19, 2016

The Girl and the Sunbird – Out Now!

So, what does it feel like to have a second novel published? It turns out, no less emotional than the first time round. Second books, compared to first, notoriously struggle. They try to live up to the first, that book you had in your bones for many, many years before you wrote it. And it’s true that The Poet’s Wife took many years to write and was born out of a passion for a place; a curiosity for an anti-fascist cause. ‘If there is a book you really want to read but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it,’ said author Toni Morrison. Well, that’s what happened with The Poet’s Wife.

But that doesn’t mean that The Girl and the Sunbird can’t be something, can’t become something. Kenya, over the past three years, has crept beneath my skin in completely unprecedented ways. The sunbird came to life in my novel because as I sat at the desk where I write in Nairobi I watched, transfixed, as these beautiful little birds hovered on the flowering foliage outside my window. How would it work, I wondered, if the sunbird became a metaphor for a person in the story I wanted to create? Who would this person be and how would they be connected to my protagonist, Iris? And so Kamau was born, the ‘sunbird’ of the novel.

I would love to know what you think of him, of Iris, of their relationship and what happens to Iris as we follow her journey over fifty years. I’m really excited about this story. Author Aminatta Forna said ‘Don’t write about what you know, write about what you want to understand.’ I knew nothing about very early colonial Nairobi where the first half of this novel is set and although I could make a fair guess how the local people (or ‘natives’ as they were then known) were generally treated by their colonisers, it wasn’t until I really started researching and peeling back layers of injustice and discrimination that I could really put this period into an authentic context. Don’t get me wrong, British colonisers did plenty of good too in East Africa (for example education, roads & transportation and “development”- though it’s important I put that last word in inverted commas). But in The Girl and the Sunbird, I’m more interested in exploring and understanding the inherent prejudice that heavily saturated colonial East Africa and how that paved the way for the turmoil of the 1950’s guerilla group, the Mau Mau.

So yes, this is a novel about institutionalised racism and the knock on effects of that. Perhaps there’s no better time for that as people our world over continue to struggle to see that we are all connected; we are all one, no matter the colour of our skin, our religion or our beliefs. My father, Harry Stonehill (whom I dedicated The Poet’s Wife to), always used to say (though I’m sure his words weren’t original!) ‘I may not always agree with you, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.’ We all need to live by this wisdom, no matter who says it and in what way they express it. This is a truth I seek in my writing.

Yet despite the aforementioned themes of the book, at heart, however, The Girl and the Sunbird is a love story. Please, tell me what you think of it. If you love it, if you’re unconvinced by it…every single piece of feedback helps make me a better writer.

Asante sana

The post The Girl and the Sunbird – Out Now! appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.

June 11, 2016

Interview with Scott Mullins from This Is Writing

An interview I did with Scott Mullins from This Is Writing is now live! Click here to read it. There were some really interesting questions which I had to think hard about, for example how I would define creativity, and what’s my greatest fear as a writer. Loved it! Thanks Scott. (Find him on twitter and facebook)

The post Interview with Scott Mullins from This Is Writing appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.

June 10, 2016

A Celebration of #WonderfulWomen – who do you nominate?

One week today, my second novel The Girl and the Sunbird will be published. To help celebrate this, in the week leading up to this I’m launching the #WonderfulWomen campaign. I’d LOVE for you to take part. Here’s what it’s all about…

Think of any female, alive or dead, personally known or unknown to you, even fictional; a woman who you think is just amazing, a woman who has inspired / encouraged / moved / helped / supported / motivated you in some way.

We all know somebody like that, right?

As I’ve got to know my character of Iris from The Girl and the Sunbird whilst working on this novel over the past couple of years, like any novelist, she has become real to me and I admire this brave, wise and curious woman hugely. Just as I often joke that I was born in the wrong century (I still write letters, don’t have a smart phone, only converted to digital photography recently…the list could go on), Iris is a woman born ahead of her time. Had she been born today, she would have been allowed to study at university, would not have been forced through the debutante “marriage mart” (Byron) debacle, could have chosen her own husband and her relationship with a man with skin a different colour from hers would be far from the scandal it was one hundred years ago. Living here in multi-cultural Nairobi, I often think of Iris when I see mixed race couples and their children with the skin of a hundred hues.

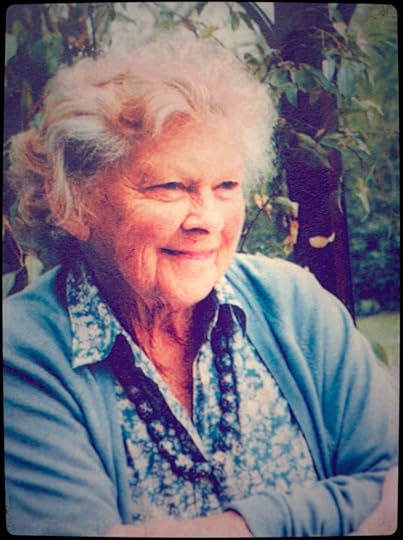

There are so, so many wonderful women I could talk about here. But I have decided to nominate my wonderful maternal grandmother, Christine Thompson. Accomplished musician, fabulous cook and conversationalist, mother to six children and grandmother to thirteen, Christine was the kind of person you simply felt good in their company, one of these people who spread a warm glow of kindness, sincerity and optimism about them. She has a brief cameo appearance in The Girl and the Sunbird (just as my father did in The Poet’s Wife), written about in a letter from Iris’s father to Iris as the ‘new organist’ at the church in Bourn, Cambridgeshire. (She really was the organist there.) I could write so much about her, but what I’d rather leave with you with a few memories and photographs:

* The way she would throw her hands high into the air when we visited, screeching with joy and excitement, the tip of her nose glowing pink

*Her infectious laugh that would go on and on, often causing tears to roll down her cheeks

* The incredible teas that Chris (also known as ‘Granny Teacups’) put on with scotch pancakes, ‘Granny biscuits’, cakes and endless cuppas piled high with sugar when the grown-ups weren’t looking.

*The way her fingers came alive at the piano and, really, any instrument she touched.

Christine in 2004, the year she died

Christine and her beloved Eric in 2002. They were married for over 60 years.

Chris and Eric’s six children, 1954. My mother is Elizabeth, the eldest

The young Christine, 1943

So, who’s the wonderful woman in your life that you’d like to nominate? Please tweet about it (with the #WonderfulWomen hashtag), put it on facebook, send me an email, leave a comment on this blog, post a photograph, whatever you can think of.

Please join me and let’s celebrate the #WonderfulWomen in our lives.

The post A Celebration of #WonderfulWomen – who do you nominate? appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.

June 3, 2016

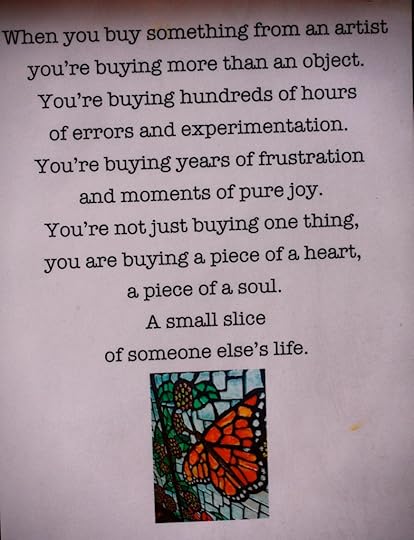

What are the implications of buying ‘art’?

Every artist amongst us, no matter the medium, pours love, time, hard work and hope into our creations. Last weekend, whilst staying at the magical Kitengela Glass in Nairobi, I came across this sign (sorry about the wonkiness of the photo):

This really, really struck me. Yes, the sentiment is not new but I love the way this is expressed. Whether we are creating a piece of music, jewellery, a book, a sculpture, poem or a screenplay, whatever creative endeavour it is, the finished result is a slice of ourselves. So this means, when we buy or even enjoy another’s piece of art, we owe it to that artist to pause and consider the complex tapestry of emotions, moments, days, months and years that have contributed to it.

‘…you are buying a piece of a heart, a piece of a soul.’

xoxo

The post What are the implications of buying ‘art’? appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.

May 29, 2016

Interview with Author Sharon Maas

Sharon Maas’ early novels were set in India, a country she has spent considerable time in and has a special connection with. Her last three novels are set in Guyana in South America where she hails from (then known as British Guiana), a fascinating and colourful backdrop for her tales of racial tension, forbidden love and family secrets.

Welcome to my blog Sharon and thanks for agreeing to answer my questions!

[image error]

Please can you tell us something about your original journey to publication?

That’s a very long story, which I’ll try to cut short! In the late 1990’s I wrote my first novel. It was over 700 pages long, and surprisingly it found an agent at the first try. She said it was terrific, but needed cutting, and she sat down with me and helped me with the culling of pages and pages of padding. I got it down to 450 pages, resubmitted it, and she tried for a year to find a publisher. At my last phone call with her I broke down in tears. But then I got up and wrote another book – that was Of Marriageable Age. When the agent didn’t get back to me (probably she was sick and tired of me by then!) I sent it to a manuscript assessment service and got help in revising it. The woman who edited it loved it so much that she sent it straight to the agent she was scouting for, and the rest is history. The new agent (from a top UK agency) rang me up and asked me to come to London (I lived in Germany), which I did immediately, and stayed at her home. A few weeks later the novel went to auction and was eventually bought by HarperCollins. It did reasonably well.

I wrote two more novels for HarperCollins, which didn’t do as well as OMA, and so it was very risky of me to write a fourth novel in a setting they thoroughly disapproved of!

The attitude then, and even now, in the publishing world is that readers aren’t brave enough to tackle books set in out-of-the-way places like Guyana, South America, so I basically gave myself a huge handicap. In the end I stayed stubborn and chose to part from HarperCollins rather than change the setting to India, which is what they wanted. I thought it would be easy enough to find a different publisher, but it wasn’t. Yet I was determined to write “Guyana” books as that is where my childhood was spent, and those experiences and memories are the treasure-house from which I write my stories. I wrote novel after novel but could not find either an agent or a publisher for ten years. It was a time of struggle, of having to pick myself off of the ground after yet another rejection, and start again.

The dawning of the digital age was my salvation. Bookouture snapped up the digital rights to Of Marriageable Age and proceeded to publish one after the other of my Guyana novels. So, one can argue as much as one wants about the relative merits of e-books and print books – e-publishing relaunched my writing career, which is now in full swing! The novel which will be published in July is called The Sugar Planter’s Daughter, and it is the first book I wrote while holding down a day-job; all the others were written during my very long maternity leave.

What were you like as a child?

Looking back, I see two sides to my child-self. On the one hand there was the extremely shy, silent little girl who could spend hours curled up with a book or simply dreaming and philosophising — yes, I had real philosophical discussions with myself on the meaning of life, God, the essence of thought, and so on.

On the other hand I was extremely adventurous. I was a tomboy and did things other girls didn’t – climb trees and so on. My best friend was an English girl whose father managed a shipping company and she lived next to the dry dock and we ran all through the place, through the machines, climbed up the ships, tightrope-walked on metal beams across abysses, and so on. I also loved swimming, going to beach or into the Interior to swim in the black-water creeks. At ten I decided I wanted to go to school in England and I went there all alone and didn’t see my parents for ages – I stayed with a foster-mother in Cumberland, one who had a riding school, as I also loved horses and wanted to be a cowboy.

So those were the two sides of my personality. I’m glad I didn’t grow up today as I would surely have been put into therapy. It can’t be healthy to be so silent, can it!

You are from Georgetown in Guyana – how would you describe this place to someone who’s never been there before?

Just about everyone who grew up in Guyana – or British Guiana, as it was called then – waxes poetic when they talk about “home”. I could describe the majestic white wooden houses nestled in luxurious gardens in Georgetown, or tell you about the magnificent forests and wildlife, the SeaWall along the Atlantic coast, the endless green fields of sugar-cane – but it still wouldn’t capture the essence of what that country means to us. It’s a feeling, really; a kind of mellow, soft, comfortable sense of belonging. I suppose everyone has this feeling about the place they spent their childhood in and every place is unique; what makes Guyana unique is particularly hard to describe and few outsiders ever go there. It’s a peculiar place; on the South American continent but in every other way, a Caribbean country: in language, culture, society, food, history, and economics, we are part of the West Indies. Yet we don’t have the transparent sea and white sand that would attract masses of tourists, which is a good thing. What we do have is a magnificent untouched Interior. With less than a million inhabitants, most of Guyana’s 83,000 square miles is uninhabited. The Guyana Shield is one of only four intact rainforest systems on the planet, and therein lies our wealth. The kind of people who visit us are those interested in nature, who don’t mind a mosquito bite or two, who travel with bird-watching binoculars rather than bikinis.

It’s a country with a fascinating history – did you know, for instance, that the Booker Prize originated there? – and it’s all a neglected part of British history. Many outsiders have never heard of it, and it’s constantly mixed up with Ghana or Guinea. It’s like, Guyana, where?

But as in the saying about Mohammed and the mountain: if the world won’t come to Guyana, I can try to bring Guyana to the world – through fiction. I try to take people there in my novels. So if you want to know, pick up one of the books!

You are also very well travelled – please tell us something about your travelling adventures and the motivation behind them?

I spoke earlier about my sense of adventure, right? Well, when I was 19 I decided to travel around South America. I gave up my journalist job, emptied whatever savings I had, and with two friends took off via the Amazon entry to Brazil. We had no idea, no plan, no itinerary – we simply went where the wind took us! That happened to be up the Amazon River towards Colombia, from there into the backlands of Peru, over the Andes to Lima and then up to Cuzco and Macchu Piccu. After that it was up the west coast of South America to Ecuador and Colombia. We lived in a commune in Ecuador for six months, from where we could take all kind of trips here and there. This was the early 70’s and South America was crawling with Americans, mostly young men escaping the Vietnam draft. It was a fantastic time, but it ended dramatically for me on a Colombian island, where I was busted for a matchbox of marijuana and thrown into jail for an indefinite length of time – they didn’t know what to do with me. I finally got out, much more sober than I’d been before.

I returned to Guyana where my friends had already arrived and we founded a farm far away from civilisation. But farming wasn’t really my thing and by then I had a burning desire to go to India to deepen the spiritual practice I had started a few months earlier. I managed to get together the money for the flight to London (I had been writing articles on my South American travels) and from there I went to Switzerland to join some friends who were also India-bound. We went overland, via Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan. And that too was an unforgettable journey.

I stayed in India almost 2 years and moved to Germany in 1975, married a German, and my life became more stable thereafter. I’ve had my base in Germany ever since, and my travels are far more conventional these days.

Before you were a writer, what were you doing?

In Germany, after divorce from my first husband, I studied Social Work. Once qualified I got a job as a “probation helper”, which means accompanying people who had a criminal conviction but were spared prison, as well as those released from prison “on probation”. That was where I met my second husband. My two children were born soon after. Following the birth of my daughter in 1990 I took an indefinite time off to be a stay at home mother and when she was five I started to write seriously.

When you are not writing, what do you do to relax?

I’m now working full time again, this time in a hospital, as well as in a home for unaccompanied underage refugees, so I don’t have much “free time”. But my daughter has been living with me for the past few months and we do things together now – go for walks in the woods or to a new town we haven’t seen before. She is a qualified Yoga teacher and she has forced me to start daily Yoga again, so that’s good, if sometimes painful! I have an old dog who needs attention and I visit my husband who sadly is very ill and in a care home nearby. My daughter and I plan a trip to Athens or some other European city later this year, if only we can organise care for the dog. I still go to India once a year and spend as much time as possible with meditation, which is the main staple in my life. I also go to Guyana once a year if possible.

And, of course, I read!

If you had to choose your favourite book of those you have written, what would it be and why?

Not fair, Rebecca! It’s like asking a mother who’s her favourite child! Certainly, Of Marriageable Age is lodged there as the book that changed everything and made me know that yes, I could write a good book that others want to read. But at the moment, my favourite book is the one coming out in July, The Sugar Planter’s Daughter. It could very well be, from a professional point of view, my best, which would make sense as I do think that with every book I become a better writer.[image error]

If you had to choose one or two of your favourite books or authors of all time, what / who would they be?

Without question, The Mahabharata, the great Indian epic. No other book has ever affected my quite as profoundly as that book; it simply wiped me out when I first read it in 1973. It’s a huge book, of course, and as I didn’t like any of the English condensations I wrote my own, which is called Sons of Gods, and self-published it.

What advice do you have for aspiring writers?

Don’t bother with what’s in trend. No need to jump on the latest literary bandwagon. Don’t try to write the next Harry Potter or Fifty Shades. Write what comes from YOU, something original that only you could write. Be true to yourself, and your writing will bring deep satisfaction to you and your readers – it’s almost like magic! If you write fiction, feel with your characters as if they were real, and that will make them real to your readers. There is so much between the lines in every novel you read, and what’s between the lines is the essence of the author. Readers feel that, even if not consciously, so make sure you give them something worth feeling!

Can you give us a peek into what you’re working on right now?

Right now I’m still finishing up the edits on The Sugar Planter’s Daughter. Then it’s back to one of the already-written novels, which needs a thorough revamp. Which book? What is it about? Ah, that’s a secret!

Like Sharon’s facebook page here. The Sugar Planter’s Daughter will be published on 22 July 2016.

The post Interview with Author Sharon Maas appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.

May 22, 2016

Five Top Quotes about Creativity & Writing to Motivate and Inspire

Time and again, we all need inspiring words to help us to write or simply live creatively, without fear or inhibitions.

Stick one or more of these quotes above your desk, keep them in your bag, write them in the sand. Or just read them as often as you can, let their wisdom seep into you and BELIEVE.

People working in the arts engage in street combat with The Fraud Police on a daily basis, because much of our work is new and not readily or conventionally categorised. When you’re an artist, nobody ever tells you or hits you with the magic wand of legitimacy. You have to hit your own head with your own handmade wand. And you feel stupid doing it. There’s no ‘correct path’ to becoming a real artist. You might think you’ll gain legitimacy by going to university, getting published, getting signed to a record label. But it’s all bullshit and it’s all in your head. You’re an artist when you say you are. And you’re a good artist when you make somebody else experience or feel something deep or unexpected.

Amanda Palmer

[image error]

Writing, when all is said and done, is an attempt to understand one’s own circumstances and to clarify the confusion of existence.

Isabel Allende

There is no such thing as a writer without influence. Those influences are very important; they help you define yourself, with them and against them. As you write more, the influences fall off.

Salman Rushdie

The mariner sails the sea because he longs to, because it is a challenge he needs, because each time he is testing himself, exploring, discovering. I write for the same reason.

Michael Morpugo

The artist is a receptacle for emotions that come from all over the place: from the sky, from the earth, from a scrap of paper, from a passing shape, from a spider’s web.

Pablo Picasso

[image error]

All of the above quotes need nothing adding to them. In their own ways, they all resonate strongly with me and help to validate why I do what I do.

What are your favourite creativity + writing quotes?

#amwriting

The post Five Top Quotes about Creativity & Writing to Motivate and Inspire appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.

May 15, 2016

Why should we read Historical Fiction?

I’m going to let you into a little secret: I never intended to write Historical Fiction. It’s not that I didn’t enjoy reading it from time to time, but in my pre-novel days when I focused on the short story form, they were almost always set in the present day. When I started putting my energies into longer fiction, I wanted to write sassy, contemporary women’s fiction with a bite, delving primarily into the nuances of human relationships and interaction. But that didn’t quite happen.

As I describe in this blog, I spent eighteen months living in the Andalucian city of Granada, finding myself spellbound by this city. I wanted to set my first novel there, but every time I started to write, the clock re-wound. My novel wanted to be set in the past. It wanted to tell a story of what happened in Granada many years ago. Perhaps this was because secrets from the past are etched into each cobble and shady courtyard and whispers echo from the surrounding mountains that overlook its inhabitants.

[image error]

As soon as I started to hear murmurs of the Spanish Civil War that has remained a taboo for over 70 years, that was it. It may not have been what I’d envisaged myself writing, but it became clear that this was my responsibility as a writer; to tell the story of what normal people experienced during this brutal period.

But back to the question I posed in the title of this blog: Why should we, as lovers of the written word, read historical fiction? I read something not long ago that addresses this beautifully:

‘ You row forward looking back, and telling this history is part of helping people navigate toward the future. We need a litany, a rosary, a sutra, a mantra, a war chant for our victories. The past is set in daylight, and it can become a torch we can carry into the night that is the future.’

Rebecca Solnit

In other words, in our world that is fraught with dangers, with war, with the devastating effects of climate change and so much more, we must look to the past in order to relate to our present; to pave our futures. I once had an interesting conversation with a taxi driver here in Nairobi – he couldn’t understand why I wanted to write about the Mau Mau (a guerrilla group in 1950’s Kenya that aimed to re-claim land from British settlers, terrorising their colonisers as well as their own people and that feature in my second novel) , to drag all that up again when it was done and buried. But I believe that if a historical fiction writer has done their job properly, we as readers can glean something of what does and does not work on a global and political scale as well as on a more personal and intimate level.

From The Well of Being by Jean-Pierre Weill

I’m not suggesting for a moment you only read historical fiction. I am a firm believer in reading widely and now and again out of your comfort zone. But compelling historical fiction holds the power to become this war chant for our victories as Solnit describes it. It can evolve into a moral compass which, in that subtle way that only books can do, can leave us more tolerant, more empathetic, more forgiving. For history is full of examples of hope and compassion amidst the most dire and depressing situations, and these examples can only engender further understanding of our fellow humans and this planet we call home.

Just as fiction has the power to change lives – history, arguably, can be one of our most captivating teachers if we allow it to be. In the words of author, educator and activist Parker Palmer, ‘To grow in love and service, you must value ignorance as much as knowledge and failure as much as success…clinging to what you already know and do well is the path to an unlived life.’

From The Well of Being by Jean-Pier re Weill

I’d love to know, what are your favourite historical fiction reads?

The post Why should we read Historical Fiction? appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.