Timothy R. Gaffney's Blog, page 3

April 1, 2019

The temperance movement and Dayton's 'whiskey candidate'

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 18.0px Cambria; -webkit-text-stroke: #042eee} p.p2 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 18.0px Cambria; -webkit-text-stroke: #042eee; min-height: 21.0px} span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; line-height: 16.0px; font: 13.0px 'Times New Roman'} span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; line-height: 16.0px; font: 13.0px 'Times New Roman'} span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

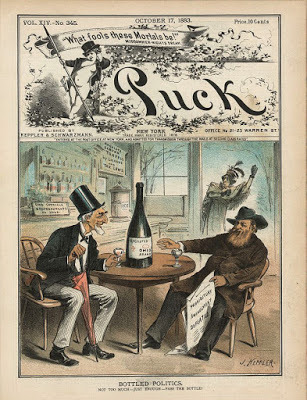

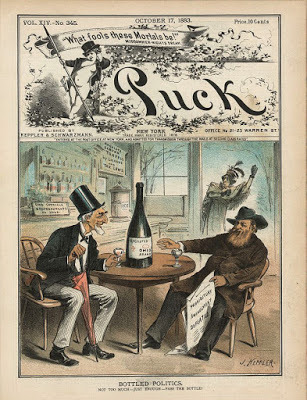

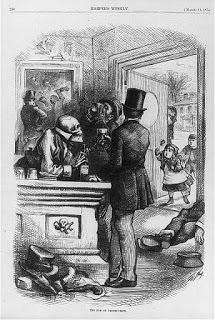

An 1878 Puck cartoon pokes fun at prohibition politics in Ohio. Source: Library of Congress

© Copyright 2019 Timothy R. Gaffney

Annie Wittenmeyer had high hopes for Dayton in the first week of April, 1874. After a month of activism, temperance crusaders here had a chance of seeing a pro-temperance candidate become the Gem City’s next mayor.

What she didn't want to see was the ascent of a type of person she loathed—a former beer brewer and a saloonist—and one of German heritage, no less. The “whiskey candidate,” she called him.

I touch on Dayton's mayoral election of 1874 in my upcoming book Dayton Beer. But here are a few details and graphics I just couldn't squeeze into my history of brewing in the Miami Valley.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; line-height: 16.0px; font: 13.0px 'Times New Roman'} span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; line-height: 16.0px; font: 13.0px 'Times New Roman'} span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

Annie Wittenmeyer. Source: History of the Woman’s Temperance Crusade .

Wittenmeyer was a native Ohioan who became a national leader of the temperance movement. Born Sarah Ann (“Annie”) Turner (1827-1900) on the Ohio River in Sandy Springs, Adams County, Wittenmeyer lived most of her life in Iowa and died in Pennsylvania. But it was back in Ohio that organizers of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) in Cleveland made her its first president in November 1874. (The WCTU still exists, by the way, in Evanston, IL.)

Wittenmeyer was a bright, educated woman who had seen and done a lot. She had opened Iowa’s first tuition-free school. During the Civil War she had visited troop encampments, organized aid programs and advocated for better treatment of wounded and sick soldiers, even overseeing all hospital kitchens for the Union army. Her organizing efforts continued after the war and eventually led her to the cause of temperance.

The WCTU grew out of the Woman’s Crusade that erupted in Ohio in the winter of 1873-74 and spread across the country. Wittenmeyer chronicled it—from her own point of view—in her 1878 book History of the Woman’s Temperance Crusade . The temperance movement was on the rise.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; line-height: 16.0px; font: 13.0px 'Times New Roman'} span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; line-height: 16.0px; font: 13.0px 'Times New Roman'} span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

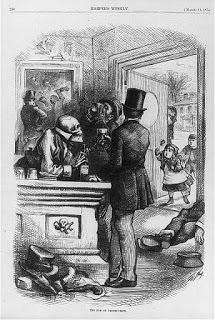

“Bar of Destruction,” a Thomas Nast cartoon in the March 21, 1874 Harper’s Weekly. Source: Library of Congress.

Dayton’s was one of several local crusades she described in vivid, even lurid detail. Then a city of about 40,000, Dayton “is a beautiful, well-built town,” she wrote, with “handsome residences, fine churches” and “substantial public buildings.” But, she went on, “many of its palaces are red with the blood of murdered innocence, and many of its massive edifices have been built with the price of souls.”

What ignited Wittenmeyer’s rhetoric was “not only the usual array of saloons, and gambling-dens, and brothels, where liquors were sold and drank but there were massive breweries, and great wholesale houses… and the business was largely in the hands of a rough class of foreigners, mainly Germans.”

Beer brewing was one of Dayton's earliest industries. Pioneer George Newcom, an Irish immigrant, added a brewery to his famed Newcom’s Tavern in 1809 or 1810. True, by Wittenmeyer’s time nearly all of Dayton’s brewers were owned by German immigrants or their first-generation descendants. The Miami Valley was a land of immigrants who had displaced its native people less than a century earlier. Beginning in the 1830s, an increasing percentage of new arrivals were German.

While allowing that “some of the best people in our land are foreigners,” Wittenmeyer, who noted her own blood line went back to the Revolutionary War, blamed immigrants—German and Irish in particular—for the drunkenness, lawlessness and poverty she saw afflicting America. “We are slowly learning the fact that we are building jails and almshouses that ought to have been built in Germany and Ireland, and that America is rapidly becoming a sewer for the moral filth of Europe,” she wrote.

So it shouldn't surprise you that she had nothing nice to say about Lawrence Butz Jr. (1839-1913,) a Dayton grocer who was seeking the mayor’s seat this week in 1874. While Butz was a native Ohioan, his father had come from Baden-Württemberg. Also, in the 1860s Lawrence Jr. had been a partner with another German immigrant, Henry Ferneding, in the City Brewery then at Warren and Brown streets.

City directories and census records show Butz later joined his father’s grocery business at 260 Warren. How much it involved sales of beer or liquor isn’t clear, but some city directories in those years also listed it under saloons.

Wittenmeyer labeled Butz “the whiskey candidate.”

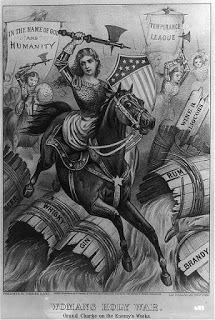

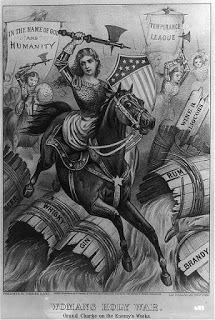

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; line-height: 16.0px; font: 12.0px Cambria; -webkit-text-stroke: #555555} span.s1 {font-kerning: none; -webkit-text-stroke: 0px #000000} span.s2 {font-kerning: none} span.s3 {font-kerning: none; color: #555555} "Woman’s holy war,” Currier & Ives lithograph, c1874. Source: Library of Congress.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; line-height: 16.0px; font: 12.0px Cambria; -webkit-text-stroke: #555555} span.s1 {font-kerning: none; -webkit-text-stroke: 0px #000000} span.s2 {font-kerning: none} span.s3 {font-kerning: none; color: #555555} "Woman’s holy war,” Currier & Ives lithograph, c1874. Source: Library of Congress.

The temperance women formed a Dayton organization in February, and on March 6 some 200 crusaders marched through rain to the saloons, which simply turned them away, according to Wittenmeyer's account. As the weather improved, more crusaders gathered in front of saloons to pray and sing.

The saloons responded. “It soon came to be known that the visit of the ladies to a saloon meant free beer and whiskey at that place, and there ‘the boys’ rallied in force like vultures over a dead carcass. The result was, more drunken men on the streets than had been since since the 4th of July,” Wittenmeyer wrote. Jeering mobs taunted them and threw “bits of bologna and crackers” at women kneeling in prayer.

No doubt the crusaders hoped a pro-temperance mayor would put an end to this sorry business. The election came Saturday, April 6—and Butz won. “This was taken by the saloon-keepers as a verdict for free whiskey,” Wittenmeyer lamented.

The police department issued a proclamation vowing to charge saloonists who permitted unruliness during temperance vigils, but the crusaders gave up the mass approach, instead visiting saloons in small groups and attempting to talk to the proprietors.

“The saloon-keepers were generally averse to these visits, and insisted that the election had settled the question,” she wrote.

Butz was mayor through 1875 and won a second term in 1878.

Wittenmeyer died in 1900 without seeing her wish fulfilled. Had it happened, Dayton today might be without its breweries and bars. And, perhaps, without many here now who are descendants of those who were immigrants in her time.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; line-height: 16.0px; font: 13.0px 'Times New Roman'} span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 18.0px Cambria; -webkit-text-stroke: #042eee} span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; line-height: 16.0px; font: 13.0px 'Times New Roman'} span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; line-height: 16.0px; font: 13.0px 'Times New Roman'} span.s1 {font-kerning: none} An 1878 Puck cartoon pokes fun at prohibition politics in Ohio. Source: Library of Congress

© Copyright 2019 Timothy R. Gaffney

Annie Wittenmeyer had high hopes for Dayton in the first week of April, 1874. After a month of activism, temperance crusaders here had a chance of seeing a pro-temperance candidate become the Gem City’s next mayor.

What she didn't want to see was the ascent of a type of person she loathed—a former beer brewer and a saloonist—and one of German heritage, no less. The “whiskey candidate,” she called him.

I touch on Dayton's mayoral election of 1874 in my upcoming book Dayton Beer. But here are a few details and graphics I just couldn't squeeze into my history of brewing in the Miami Valley.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; line-height: 16.0px; font: 13.0px 'Times New Roman'} span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; line-height: 16.0px; font: 13.0px 'Times New Roman'} span.s1 {font-kerning: none} Annie Wittenmeyer. Source: History of the Woman’s Temperance Crusade .

Wittenmeyer was a native Ohioan who became a national leader of the temperance movement. Born Sarah Ann (“Annie”) Turner (1827-1900) on the Ohio River in Sandy Springs, Adams County, Wittenmeyer lived most of her life in Iowa and died in Pennsylvania. But it was back in Ohio that organizers of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) in Cleveland made her its first president in November 1874. (The WCTU still exists, by the way, in Evanston, IL.)

Wittenmeyer was a bright, educated woman who had seen and done a lot. She had opened Iowa’s first tuition-free school. During the Civil War she had visited troop encampments, organized aid programs and advocated for better treatment of wounded and sick soldiers, even overseeing all hospital kitchens for the Union army. Her organizing efforts continued after the war and eventually led her to the cause of temperance.

The WCTU grew out of the Woman’s Crusade that erupted in Ohio in the winter of 1873-74 and spread across the country. Wittenmeyer chronicled it—from her own point of view—in her 1878 book History of the Woman’s Temperance Crusade . The temperance movement was on the rise.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; line-height: 16.0px; font: 13.0px 'Times New Roman'} span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; line-height: 16.0px; font: 13.0px 'Times New Roman'} span.s1 {font-kerning: none} “Bar of Destruction,” a Thomas Nast cartoon in the March 21, 1874 Harper’s Weekly. Source: Library of Congress.

Dayton’s was one of several local crusades she described in vivid, even lurid detail. Then a city of about 40,000, Dayton “is a beautiful, well-built town,” she wrote, with “handsome residences, fine churches” and “substantial public buildings.” But, she went on, “many of its palaces are red with the blood of murdered innocence, and many of its massive edifices have been built with the price of souls.”

What ignited Wittenmeyer’s rhetoric was “not only the usual array of saloons, and gambling-dens, and brothels, where liquors were sold and drank but there were massive breweries, and great wholesale houses… and the business was largely in the hands of a rough class of foreigners, mainly Germans.”

Beer brewing was one of Dayton's earliest industries. Pioneer George Newcom, an Irish immigrant, added a brewery to his famed Newcom’s Tavern in 1809 or 1810. True, by Wittenmeyer’s time nearly all of Dayton’s brewers were owned by German immigrants or their first-generation descendants. The Miami Valley was a land of immigrants who had displaced its native people less than a century earlier. Beginning in the 1830s, an increasing percentage of new arrivals were German.

While allowing that “some of the best people in our land are foreigners,” Wittenmeyer, who noted her own blood line went back to the Revolutionary War, blamed immigrants—German and Irish in particular—for the drunkenness, lawlessness and poverty she saw afflicting America. “We are slowly learning the fact that we are building jails and almshouses that ought to have been built in Germany and Ireland, and that America is rapidly becoming a sewer for the moral filth of Europe,” she wrote.

So it shouldn't surprise you that she had nothing nice to say about Lawrence Butz Jr. (1839-1913,) a Dayton grocer who was seeking the mayor’s seat this week in 1874. While Butz was a native Ohioan, his father had come from Baden-Württemberg. Also, in the 1860s Lawrence Jr. had been a partner with another German immigrant, Henry Ferneding, in the City Brewery then at Warren and Brown streets.

City directories and census records show Butz later joined his father’s grocery business at 260 Warren. How much it involved sales of beer or liquor isn’t clear, but some city directories in those years also listed it under saloons.

Wittenmeyer labeled Butz “the whiskey candidate.”

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; line-height: 16.0px; font: 12.0px Cambria; -webkit-text-stroke: #555555} span.s1 {font-kerning: none; -webkit-text-stroke: 0px #000000} span.s2 {font-kerning: none} span.s3 {font-kerning: none; color: #555555} "Woman’s holy war,” Currier & Ives lithograph, c1874. Source: Library of Congress.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; line-height: 16.0px; font: 12.0px Cambria; -webkit-text-stroke: #555555} span.s1 {font-kerning: none; -webkit-text-stroke: 0px #000000} span.s2 {font-kerning: none} span.s3 {font-kerning: none; color: #555555} "Woman’s holy war,” Currier & Ives lithograph, c1874. Source: Library of Congress. The temperance women formed a Dayton organization in February, and on March 6 some 200 crusaders marched through rain to the saloons, which simply turned them away, according to Wittenmeyer's account. As the weather improved, more crusaders gathered in front of saloons to pray and sing.

The saloons responded. “It soon came to be known that the visit of the ladies to a saloon meant free beer and whiskey at that place, and there ‘the boys’ rallied in force like vultures over a dead carcass. The result was, more drunken men on the streets than had been since since the 4th of July,” Wittenmeyer wrote. Jeering mobs taunted them and threw “bits of bologna and crackers” at women kneeling in prayer.

No doubt the crusaders hoped a pro-temperance mayor would put an end to this sorry business. The election came Saturday, April 6—and Butz won. “This was taken by the saloon-keepers as a verdict for free whiskey,” Wittenmeyer lamented.

The police department issued a proclamation vowing to charge saloonists who permitted unruliness during temperance vigils, but the crusaders gave up the mass approach, instead visiting saloons in small groups and attempting to talk to the proprietors.

“The saloon-keepers were generally averse to these visits, and insisted that the election had settled the question,” she wrote.

Butz was mayor through 1875 and won a second term in 1878.

Wittenmeyer died in 1900 without seeing her wish fulfilled. Had it happened, Dayton today might be without its breweries and bars. And, perhaps, without many here now who are descendants of those who were immigrants in her time.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; line-height: 16.0px; font: 13.0px 'Times New Roman'} span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 18.0px Cambria; -webkit-text-stroke: #042eee} span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

Published on April 01, 2019 03:37

March 25, 2019

How Dayton breweries stepped up after the 1913 flood

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; line-height: 13.0px; font: 14.0px Arial; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000} p.p2 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 14.0px Arial; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000} p.p3 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 14.0px Arial; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000; min-height: 16.0px} p.p4 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; line-height: 13.0px; font: 14.0px Arial; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000; min-height: 16.0px} p.p5 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; line-height: 11.0px; font: 14.0px Arial; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000; min-height: 16.0px} p.p6 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; line-height: 11.0px; font: 14.0px Arial; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000} p.p7 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; line-height: 15.0px; font: 14.0px Arial; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000} span.s1 {font-kerning: none} span.s2 {text-decoration: underline ; font-kerning: none; color: #042eee; -webkit-text-stroke: 0px #042eee}

Panoramic view of the aftermath of flood and fire in 1913 Dayton. Image from Library of Congress.

Panoramic view of the aftermath of flood and fire in 1913 Dayton. Image from Library of Congress.

© Copyright 2019 Timothy R. Gaffney

On this date in 1913, days of unrelenting rain culminated in the Great Flood of 1913. Nowhere was the destruction worse than in here in Dayton: levees collapsed and destructive floodwaters swept through the center of town. Adding to the calamity, gas lines broke and fires blazed even as rushing waters engulfed the Gem City.

Rivers have always played a huge role in the Miami Valley’s history, so it shouldn't surprise us that the region’s greatest natural disaster involved its rivers. But breweries played a role in relief efforts, as I learned while researching my book Dayton Beer.

Up and down the Miami Valley and in surrounding states, the flooding that year was one of the worst natural disasters on record. I grew up hearing stories about it from my parents, who handed them down from their parents, who had gone through it in Dayton.

The scale of the devastation is hard to imagine today. Before I tell you about the part beer played, take a look at this amazing footage of the 1913 flood, published by the University of Dayton on YouTube.

John H. Patterson (1844-1922,) founder of the National Cash Register (NCR) Company, was already famous for his pioneering business practices, while others attacked him for flaunting antitrust laws. But when the flood struck, he became Dayton’s hero for ordering NCR to shut down production and focus all of its massive resources on rescue and relief efforts. Unidentified people in an NCR boat escaping the 1913 Dayton flood. Image from Library of Congress.

Unidentified people in an NCR boat escaping the 1913 Dayton flood. Image from Library of Congress.

Among many other things, NCR turned out hundreds of boats for rescue operations. Family legend has it that my maternal grandfather, Ray Stoddard, used an NCR boat to rescue someone from a second-story window. (He loved to fish but had little money, and I’ve always wondered if NCR ever saw that boat again.)

NCR was in a good position to help. Aware of past floods that had struck the city, Patterson had NCR built on high ground. It even had its own water system, so it was able to produce clean drinking water after the flood contaminated public water supplies.

But Dayton’s breweries also had water systems. By the turn of the 20th century, breweries were increasingly producing ice as well as beer, not only to chill their lagering cellars but to sell as a commercial product. At least some breweries pumped massive amounts of water from wells sunk into the region’s aquifers rather than take it from the river.

Flood waters on Ludlow Street in downtown Dayton during the 1913 flood. Image from Library of Congress.

Flood waters on Ludlow Street in downtown Dayton during the 1913 flood. Image from Library of Congress.

Adam Schantz's Riverside Brewery was such a case. Although it was built on the bank of the Great Miami River just east of Salem Avenue, it drew its water from wells. As early as 1899, an article in the June 10 editions of the Dayton Daily News praised the “clearness and beauty” of the brewery’s well water. But the brewery also treated the water, passing it through a complex mineral-stripping process to produce what became known as “Lily water.” Schantz sold it as a separate product.

Breweries outside Dayton also chose the aquifer over the river. A June 27, 1915 article in the Auglaize Republican described the beer-making process of the City Brewing Co.in Wapakoneta: “It would afford you much satisfaction to see the water, which is soft and clear as crystal in its natural state, pumped from their deep wells into their huge boilers,” it reported. That wasn't the end of it: the Wapakoneta brewery then boiled the water, condensed it and passed it through a charcoal filter before transforming it into beer.

This attention to water quality in the brewing process meant breweries had great capacity to produce drinking water after the flood. In Dayton at least, and perhaps elsewhere, breweries became part of the relief effort. I found just a few lines about it in a Dayton Daily News report on a Dayton Board of Education meeting: “… The Dayton Breweries Company and the Olt Brewing Company were thanked for water service furnished the schools while the city water was still in the unpurified state,” noted the May 2, 1913 article.

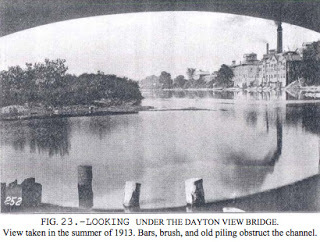

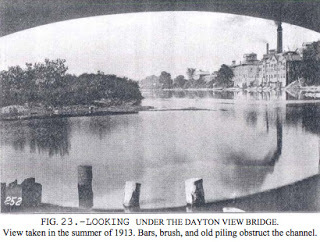

View of the Riverside Brewery from beneath the Dayton View Bridge. From Bock,

History of the Miami Flood Control Project

, page 57.

View of the Riverside Brewery from beneath the Dayton View Bridge. From Bock,

History of the Miami Flood Control Project

, page 57.

Adam Schantz Jr. (1867-1921) played an even bigger role. The son of the Riverside Brewery’s founder, Schantz had become president of the combined Dayton Breweries Co. After the flood, Governor Cox appointed him to the Dayton Citizens' Relief Committee, with Patterson as chairman, according to C. A. Bock’s History of the Miami Flood Control Project .

Beyond providing inspirational leadership, Schantz “contributed $60,000 personally and another $60,000 from the (Schantz) estate for the restoration work,” the February 15, 1921 Brewers Journal reported.

Some of Schantz’s philanthropy came in the form of the old Riverside Brewery and some of the Schantz estate’s personal property, according to the January 1919 Miami Conservancy Bulletin .

The Miami Conservancy District, formed in 1915 to create a system of dams and levees to prevent a repeat of the 1913 flood, determined it needed to widen the Miami River in downtown. Built on the river’s west bank, the Riverside Brewery stood in the way.

Its time had passed anyway, as Prohibition had forced it and Dayton's other breweries to cease beer production and the Dayton Breweries Co. itself would soon be out of business. Schantz donated not only the brewery but the neighboring site of his parents' original home, according to the Bulletin.

I found little else describing the role of brewers and breweries in the great flood of 1913, but I suspect there are other stories out there. What can you add to it?

Panoramic view of the aftermath of flood and fire in 1913 Dayton. Image from Library of Congress.

Panoramic view of the aftermath of flood and fire in 1913 Dayton. Image from Library of Congress.© Copyright 2019 Timothy R. Gaffney

On this date in 1913, days of unrelenting rain culminated in the Great Flood of 1913. Nowhere was the destruction worse than in here in Dayton: levees collapsed and destructive floodwaters swept through the center of town. Adding to the calamity, gas lines broke and fires blazed even as rushing waters engulfed the Gem City.

Rivers have always played a huge role in the Miami Valley’s history, so it shouldn't surprise us that the region’s greatest natural disaster involved its rivers. But breweries played a role in relief efforts, as I learned while researching my book Dayton Beer.

Up and down the Miami Valley and in surrounding states, the flooding that year was one of the worst natural disasters on record. I grew up hearing stories about it from my parents, who handed them down from their parents, who had gone through it in Dayton.

The scale of the devastation is hard to imagine today. Before I tell you about the part beer played, take a look at this amazing footage of the 1913 flood, published by the University of Dayton on YouTube.

John H. Patterson (1844-1922,) founder of the National Cash Register (NCR) Company, was already famous for his pioneering business practices, while others attacked him for flaunting antitrust laws. But when the flood struck, he became Dayton’s hero for ordering NCR to shut down production and focus all of its massive resources on rescue and relief efforts.

Unidentified people in an NCR boat escaping the 1913 Dayton flood. Image from Library of Congress.

Unidentified people in an NCR boat escaping the 1913 Dayton flood. Image from Library of Congress.Among many other things, NCR turned out hundreds of boats for rescue operations. Family legend has it that my maternal grandfather, Ray Stoddard, used an NCR boat to rescue someone from a second-story window. (He loved to fish but had little money, and I’ve always wondered if NCR ever saw that boat again.)

NCR was in a good position to help. Aware of past floods that had struck the city, Patterson had NCR built on high ground. It even had its own water system, so it was able to produce clean drinking water after the flood contaminated public water supplies.

But Dayton’s breweries also had water systems. By the turn of the 20th century, breweries were increasingly producing ice as well as beer, not only to chill their lagering cellars but to sell as a commercial product. At least some breweries pumped massive amounts of water from wells sunk into the region’s aquifers rather than take it from the river.

Flood waters on Ludlow Street in downtown Dayton during the 1913 flood. Image from Library of Congress.

Flood waters on Ludlow Street in downtown Dayton during the 1913 flood. Image from Library of Congress.Adam Schantz's Riverside Brewery was such a case. Although it was built on the bank of the Great Miami River just east of Salem Avenue, it drew its water from wells. As early as 1899, an article in the June 10 editions of the Dayton Daily News praised the “clearness and beauty” of the brewery’s well water. But the brewery also treated the water, passing it through a complex mineral-stripping process to produce what became known as “Lily water.” Schantz sold it as a separate product.

Breweries outside Dayton also chose the aquifer over the river. A June 27, 1915 article in the Auglaize Republican described the beer-making process of the City Brewing Co.in Wapakoneta: “It would afford you much satisfaction to see the water, which is soft and clear as crystal in its natural state, pumped from their deep wells into their huge boilers,” it reported. That wasn't the end of it: the Wapakoneta brewery then boiled the water, condensed it and passed it through a charcoal filter before transforming it into beer.

This attention to water quality in the brewing process meant breweries had great capacity to produce drinking water after the flood. In Dayton at least, and perhaps elsewhere, breweries became part of the relief effort. I found just a few lines about it in a Dayton Daily News report on a Dayton Board of Education meeting: “… The Dayton Breweries Company and the Olt Brewing Company were thanked for water service furnished the schools while the city water was still in the unpurified state,” noted the May 2, 1913 article.

View of the Riverside Brewery from beneath the Dayton View Bridge. From Bock,

History of the Miami Flood Control Project

, page 57.

View of the Riverside Brewery from beneath the Dayton View Bridge. From Bock,

History of the Miami Flood Control Project

, page 57.Adam Schantz Jr. (1867-1921) played an even bigger role. The son of the Riverside Brewery’s founder, Schantz had become president of the combined Dayton Breweries Co. After the flood, Governor Cox appointed him to the Dayton Citizens' Relief Committee, with Patterson as chairman, according to C. A. Bock’s History of the Miami Flood Control Project .

Beyond providing inspirational leadership, Schantz “contributed $60,000 personally and another $60,000 from the (Schantz) estate for the restoration work,” the February 15, 1921 Brewers Journal reported.

Some of Schantz’s philanthropy came in the form of the old Riverside Brewery and some of the Schantz estate’s personal property, according to the January 1919 Miami Conservancy Bulletin .

The Miami Conservancy District, formed in 1915 to create a system of dams and levees to prevent a repeat of the 1913 flood, determined it needed to widen the Miami River in downtown. Built on the river’s west bank, the Riverside Brewery stood in the way.

Its time had passed anyway, as Prohibition had forced it and Dayton's other breweries to cease beer production and the Dayton Breweries Co. itself would soon be out of business. Schantz donated not only the brewery but the neighboring site of his parents' original home, according to the Bulletin.

I found little else describing the role of brewers and breweries in the great flood of 1913, but I suspect there are other stories out there. What can you add to it?

Published on March 25, 2019 03:00