Timothy R. Gaffney's Blog, page 2

July 22, 2019

Dayton Beer here! Books finally in hand

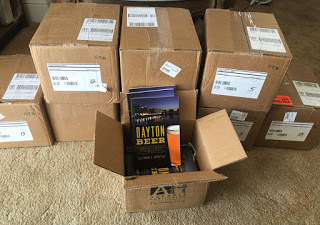

Here's what 300 copies of Dayton Beer looked like on my front porch.

Here's what 300 copies of Dayton Beer looked like on my front porch.© 2019 Timothy R. Gaffney

This is how my front porch looked the other day. I finally have books in hand—300 of ‘em. They should also be showing up in local stores, and I’ll publish a list of places carrying the book as soon as I get it.

Below is how my living room looked a few minutes later. I hope to be selling and signing a good portion of these books in the near future on my History and a Pint™ book tour.

Welcome to my living room.

Welcome to my living room.I hope you'll join me to talk about local brewing history over a pint, but you must do one of two things: 1), show up; or 2), find my event page on Facebook and click “Going,” and then show up.

I’ll save you the searching. I made all the event pages under one Facebook business page, “Dayton Beer Book Tour.”

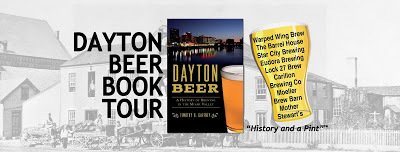

Facebook page cover image for Dayton Beer Book Tour

Facebook page cover image for Dayton Beer Book TourAnd here are links to each individual Facebook event page:

Wednesday Aug 7—5:00 pm

Warped Wing Brewing Co.

26 Wyandot St. Dayton

Thursday Aug 15—5:30 pm

The Barrel House

417 E. Third St. Dayton

Friday Aug 23—5:30 pm

Star City Brewing Co.

320 S. 2nd St. Miamisburg

Tuesday Sep 10—6 pm

Eudora Brewing Co.

3022 Wilmington Pike, Dayton

Wednesday Sep 18—6 pm

Lock 27 Brewing

329 E. First St. Dayton

Saturday, Oct 5—3 pm

Carillon Brewing Co.

1000 Carillon Blvd. Dayton

Saturday, Oct 12—1 pm

Moeller Brew Barn-Maria Stein

8016 Marion Dr. Maria Stein

Thursday Oct 17—6 pm

Mother Stewart's Brewing

109 W. North St. Springfield

If you don't use (or don't like) Facebook, you can grab a PDF copy of my schedule by clicking here.

About Dayton Beer

Beer brewing was one of the Miami Valley's first industries. From Minster's small but mighty Wooden Shoe brewery to Dayton's big brewing combine, breweries filled our glasses across the region until Prohibition obliterated them nearly overnight. Dayton Beer reveals the history and rebirth of brewing in Dayton and six Ohio counties—Auglaize, Clark, Darke, Miami, Montgomery and Shelby.

Published on July 22, 2019 03:49

July 8, 2019

Dayton brewing: lights, camera, beer

Mike Morgan (in blue) interviews me at Fifth Street Brew Pub. Photo courtesy Bret Kallmann Baker.

Mike Morgan (in blue) interviews me at Fifth Street Brew Pub. Photo courtesy Bret Kallmann Baker.

Dayton Beer isn’t out yet, but it seems to be drawing more attention already to Dayton’s brewing history.

A few weeks ago, I got a query out of the blue from Michael D. Morgan of Newport, Ky. He wanted to interview me for a web TV episode about Dayton’s brewing past.

To be honest, my book has been so all-consuming that I’ve only paid attention to Cincinnati when it related to the brewers and breweries I was writing about in Dayton and surrounding counties.

So I wasn't very familiar with Morgan, but I quickly learned he's the resident expert on brewing history in the Cincinnati region as president of Queen City History & Education. He teaches "Hops and History" at the University of Cincinnati and serves as curator of Cincinnati's Brewing Heritage Trail. He also hosts a weekly radio show called Barstool Perspective on Radio Artifact, and he’s written two books about Cincinnati’s brewing history, most recently Cincinnati Beer , released in April.

As it turns out, we have more in common than our interests in writing, history and beer. We share the same publisher, The History Press (a part of Arcadia Publishing Inc.)

But writing, teaching, leading tours and doing radio shows isn’t enough for Morgan: as I understand it, my interview is to be a part of a web TV episode about Dayton brewing, which in turn would be a part of a series he’s begun to post on YouTube.com’s “Brew Skies” channel in collaboration with Seven/Seventy-Nine, a Cincinnati video company.

So far, they’ve released one episode, “Wild Yeast and the Missing Linck.”

It’s a fascinating documentary about their discovery of a 150-year-old strain of brewing yeast in the long-abandoned cellar of the defunct Linck Brewery, and the production earlier this year of a new golden ale —dubbed Missing Linck, of course—by Josh Elliott, Urban Artifact’s head of barrel-aged beer and an expert on wild-yeast and sour beers.

So on Saturday, June 29, I sat down on the back of the patio at Fifth Street Brew Pub with Morgan and a co-interviewer, Bret Kallmann Baker of Urban Artifact, facing across a barrel at the Seven/Seventy-Nine video crew and a battery of cameras and lights.

As interviews go, it was pretty easygoing, moreso as I sipped my way though a pint of Fifth Street’s Icebreaker IPA.

I don’t know if Morgan got anything useful from me, or if I just wasted a lot of perfectly good pixels. But if an episode about Dayton brewing appears—with or without me—I’ll post an update with a link to the episode. Fingers crossed.

P.S. Autographed copies of Cincinnati Beer are available now on Morgan's website. Dayton Beer is due out July 22. Check my previous post for a schedule of my upcoming book tour, History and a Pint™, or download this flyer.

Published on July 08, 2019 03:52

July 2, 2019

Dayton Beer's 'History and a Pint' Tour

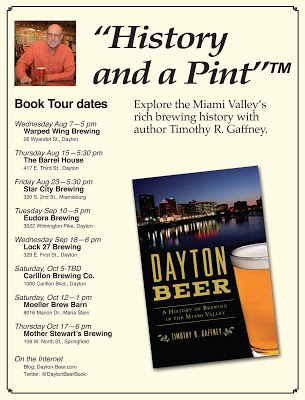

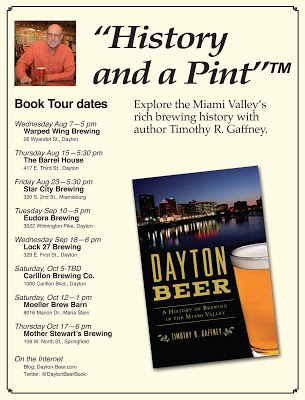

Printable flyer for 'History and a Pint'™ book tour

Printable flyer for 'History and a Pint'™ book tour© 2019 Timothy R. Gaffney

Want to know how I feel right now?

Just climb into a barrel, have someone seal it, and then have them toss you over Niagara Falls.

I always get this sense of an inexorable, uncontrollable rush as my book approaches publication. Dayton Beer is scheduled to come off the press by July 22, and less than three weeks later—August 7—I'll launch my book tour, History and a Pint™, at Warped Wing Brewing. After that, I'll be visiting one brewpub and tap house after another in rapid succession.

And there's no turning back. I'm already over the falls. Dayton Daily News food columnist Mark Fisher saw to that on Monday, July 1, when he published the first review of my book. Now, it's official.

This will be different from anything I've tried before. I'm used to signing books in book shops and at traditional speaking events. With Dayton Beer, it just seemed more appropriate to ask brewpubs and tap houses to host my events. I mean, if we're going to talk about beer history, let's do it over a beer.

Fortunately, places that sell really good beer agreed, and I'm grateful that several establishments have agreed to host me. So, here's where you'll find me from August through October:

Wednesday Aug 7—5:00 pm

Warped Wing Brewing Co.

26 Wyandot St. Dayton

Thursday Aug 15—5:30 pm

The Barrel House

417 E. Third St. Dayton

Friday Aug 23—5:30 pm

Star City Brewing Co.

320 S. 2nd St. Miamisburg

Tuesday Sep 10—6 pm

Eudora Brewing Co.

3022 Wilmington Pike, Dayton

Wednesday Sep 18—6 pm

Lock 27 Brewing

329 E. First St. Dayton

Saturday, Oct 5—3 pm

Carillon Brewing Co.

1000 Carillon Blvd. Dayton

Saturday, Oct 12—1 pm

Moeller Brew Barn-Maria Stein

8016 Marion Dr. Maria Stein

Thursday Oct 17—6 pm

Mother Stewart's Brewing

109 W. North St. Springfield

Check back with my blog for future events.

Published on July 02, 2019 07:14

June 17, 2019

Brewing history just won't stand still

Another brewer has leased the former Eudora Brewing location in Kettering, according to a news report. Gaffney photo.

Another brewer has leased the former Eudora Brewing location in Kettering, according to a news report. Gaffney photo.© 2019 Timothy R. Gaffney

Call this errata sheet no. 1. As Dayton Beer heads for the printer, this region's brewing history just won't stand still.

I've been boasting that my new history of brewing in the Miami Valley includes a complete, up-to-date directory of all the brewpubs from Dayton to Grand Lake.

But that's about to change, according to Mark Fisher, retail and restaurants reporter for the Dayton Daily News.

Last weekend, Fisher broke the news that another brewery is on its way. Pat Sullivan, the brewer behind Nowhere in Particular, has signed a lease for a space at 4716 Wilmington Pike in Kettering—the space that was the home of Eudora Brewing Co. until it moved to larger quarters at 3022 Wilmington Pike.

Sullivan (aka Charlie Navillus) is known in brewing circles as a wandering brewer who makes use (with permission) of others' systems when they have tanks to fill.

He previously set up shop with some partners in a century-old brick house in Columbus dubbed Somewhere in Particular. He will continue brewing there even as he fires up the kettle here, Fisher reported.

It's great to hear there's still energy in the craft brewery movement. But Sullivan needn't hurry on my account: Dayton Beer will be out in about a month, and I'd Iike to be able to claim it's up to date, if only for one brief, shining moment.

That's the trouble with the march of history. It never stops marching.

Published on June 17, 2019 03:32

May 13, 2019

6 brewers salute Apollo 11

© 2019 Timothy R. Gaffney

America's celebrating the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11 this year, and several brewers are stepping up to mark the occasion with special beers. This gives us an excuse to taste a lot of new beer, and it's bringing out a lot of new Apollo 11 anniversary bottles and cans for breweriana fans.

In case you missed it: the Apollo 11 mission was America's third manned mission to the moon and the first to attempt a landing. Wapakoneta native Neil A. Armstrong, mission commander, blasted off from Kenney Space Center on July 16, 1969, with Edwin E. "Buzz" Aldrin and Michael Collins. Four days later, Armstong and Aldrin touched down on the moon while Collins remained in lunar orbit. They returned to earth on July 24.

Why celebrate Apollo by brewing beer? For starters, many beers these days are made with Apollo hops, a new variety of hops created in 2000 by cross-pollinating other hop plants. Another reason is, why not?

So, what's brewin' now?

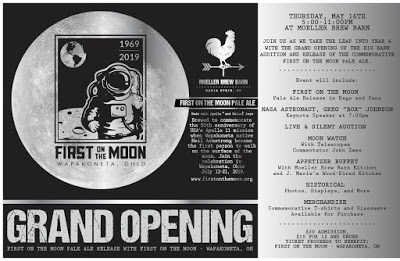

Moeller Brew Barn

Moeller Brew Barn's First on the Moon Pale Ale announcement.

Moeller Brew Barn's First on the Moon Pale Ale announcement.Here in Ohio, Moeller Brew Barn in Maria Stein has a new release on the launch pad: First On the Moon Pale Ale. Just 26 highway miles from the Armstrong Air and Space Museum in Wapakoneta, Moeller is commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission and Wapakoneta native Armstrong's achievement as the first human to walk on the moon.

It's also promoting Wapakoneta's First on the Moon community celebration, a series of events from July 12 to July 21.

Moeller will host the beer release at its Brew Barn, combining it with the brewery's fourth anniversary celebration. A variety of activities will include an appearance by former NASA Astronaut Gregory "Box" Johnson and an evening moon gaze with the moon nearly full. A silent and live auction, merchandise sales and a $20 admission fee ($10 for children) will help raise money for Wapakoneta's First on the Moon program.

Land-Grant Brewing

Land-Grant's Tranquility Base Black IPA.

Land-Grant's Tranquility Base Black IPA.Moeller isn't the only Ohio brewer celebrating Apollo. In Columbus, the Land-Grant Brewing Co. blasted off its Space-Grant Series in 2015 with EF-1, a black IPA, in celebration of the re-opening of the Center of Science and Industry's (COSI's) planetarium.

Since then it's added five more beers to the series: Gravity Wave (2016,) Godspeed (2017,) Binary Star (2018,) CubeRRT (2018) and Tranquility Base (2019.) All are black IPAs except CubeRRT, an extra pale ale.

Celestial Beerworks

Celestial Beerworks' Apollo 11 IPA. Photo courtesy Celestial Beerworks.

Celestial Beerworks' Apollo 11 IPA. Photo courtesy Celestial Beerworks.Down in Dallas, Texas, Celestial Beerworks just opened in 2018, but it boasts a series of Apollo-themed ales, from Apollo 11 and Lunar to the whimsically named Buzz Ale-Drin. A picture of its tap room in the Dallas Observer shows Apollo-themed decor.

Clandestine Brewing

Clandestine Brewing's Apollo-11 Double IPA in cans. Photo Courtesy Clandestine Brewing.

Clandestine Brewing's Apollo-11 Double IPA in cans. Photo Courtesy Clandestine Brewing.San Jose, Calif.-based Clandestine Brewing dramatically depicts the mighty Apollo-Saturn rocket on its cans of Apollo-11, a double IPA. Apollo-11 was Clandestine's first can release in 2018, and the company says it will bring it back in July for the space mission's anniversary.

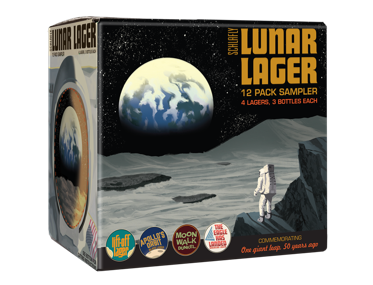

Schlafly Beer

Schlafly Beer's bottled Lunar Lager series comes in 12-packs. Photo courtesy Schlafly Beer.

Schlafly Beer's bottled Lunar Lager series comes in 12-packs. Photo courtesy Schlafly Beer.A commemorative 12-pack is available from Schlafly Beer in St. Louis, Mo. In April, Schlafly released Lunar Lager, a sampler pack that includes Lift-Off Lager, Apollo’s Orbit Black Lager, Moon Walk Dunkel and The Eagle Has Landed American Lager.

Started in 1991, Schlafly is one of the elders of the independent craft beer movement. It bills itself as "Missouri’s largest locally owned, independent craft brewery." Of course, there's this other brewery in St. Louis...

Budweiser

Six-pack of Budweiser Discovery Reserve American Red Lager. Photo: Budweiser.

Six-pack of Budweiser Discovery Reserve American Red Lager. Photo: Budweiser.Nearly simultaneously with Schlafly, Anheuser Busch-InBev announced an anniversary-themed release by its mega-brand Budweiser, the Discovery Reserve American Red Lager.

A Budweiser press release said Discovery Reserve's package design "is inspired by the past while recognizing the future; the 11 stars represent the Apollo 11 mission and the alternating bottle caps represent both our footsteps on the Moon and our next frontier, Mars. The historic Anheuser-Busch A & Eagle has also been updated to reflect the red planet with the Earth in the background. Finally, each bottle features wings and stars inspired by the original Budweiser cans."

It's entirely appropriate for Bud to salute Apollo 11. After all, NASA's mission patch looked more than a little like the Budweiser eagle.

It's entirely appropriate for Bud to salute Apollo 11. After all, NASA's mission patch looked more than a little like the Budweiser eagle.I can't end this post with a nod to irony. Leave it to Jeff Bezos, the world's richest man and founder of Amazon.com, to turn the whole Apollo-beer connection on its head. Bezos also owns a rocket company named Blue Origin, and last week he announced the company's newest venture: a moon-lander designed to carry cargo to the moon in support of the next wave of human missions there.

Its name? Blue Moon.

I wonder if it comes with a slice of orange.

Amazon.com isn't booking rides on Blue Moon, but it is taking pre-orders for my book, Dayton Beer: A History of Brewing in the Miami Valley .

Published on May 13, 2019 02:59

May 6, 2019

17 Miami Valley brewpubs near bike trails

A group of cyclists at Warped Wing Brewing Co. Photo courtesy Warped Wing.

A group of cyclists at Warped Wing Brewing Co. Photo courtesy Warped Wing.© 2019 Timothy R. Gaffney

Rails to trails to... ales?

If you're riding or walking on a recreational trail in Ohio's Miami Valley, odds are good you'll pass close to a craft beer brewpub or tap house.

With Bike Miami Valley's 2019 Miami Valley Cycling Summit coming up—Friday, May 10, in Miamisburg—I decided to see how many local brew pubs and tap houses I could find within a mile of one of the region’s recreation trails in the area covered in my book Dayton Beer: A History of Brewing in the Miami Valley.

I found 17 Miami Valley brewpubs near bike trails. I wasn’t too surprised, for a couple of reasons.

First, the Miami Valley boasts a network of than 340 miles of paved, multi-use recreational trails—the nation’s largest, according to Five Rivers Metroparks. A trail runs close to many of our local destinations.

Second, brewers down through the years have tended to locate their breweries near canals, rivers or railroads. They were all important transportation arteries at different times, and brewers need to be close to sources of water or supplies. Many of the Miami Valley’s recreation trails were created by converting abandoned railroad lines—aka the rails to trails movement—and some follow scenic streams.

Wild hops grow along the Little Miami Scenic Trail between Xenia and Yellow Springs. Photo by Timothy R. Gaffney.

Wild hops grow along the Little Miami Scenic Trail between Xenia and Yellow Springs. Photo by Timothy R. Gaffney.Nowhere is this historical connection clearer than along a stretch of the Little Miami Scenic Trail between Xenia and Yellow Springs. Ride slowly or stroll along the trail in late summer and you should spot bunches of cone-shaped hop flowers hanging from woody bines that snake through the shrubs and trees along the path.

The trail follows the path of the old Little Miami Railroad. In the 1800s, many local farmers grew hops to supply the region’s breweries. These now-wild hops may be descendants of some that spilled or were blown from passing freight trains on their way to local breweries from nearby farms.

The Yellow Springs Brewery opens onto the Little Miami Scenic Trail. Photo courtesy Yellow Springs Brewery.

The Yellow Springs Brewery opens onto the Little Miami Scenic Trail. Photo courtesy Yellow Springs Brewery.This stretch of trail also sports a brew pub that opens directly onto the path: Yellow Springs Brewery in Yellow Springs. A patio off the taproom gives a pleasant view of the trail, and cyclists can pull off for a pint.

About 10 miles down the trail, Devil Wind Brewing faces South Detroit Street, which the trail follows a short distance on its way through town. It's also just 1,600 feet up the trail from Xenia Station, a major hub in the trail network.

Bicycling is fun. Drinking beer is fun. But do them together in moderation. Don’t make a fool of yourself and a danger to others; in bicycling, getting “tipsy” is more than a figure of speech. And for serious cyclists, too much alcohol can hinder your recovery for your next ride.

Barrel House tap house is close to bike trails in downtown Dayton. Photo courtesy Barrel House.

Barrel House tap house is close to bike trails in downtown Dayton. Photo courtesy Barrel House.Here are the breweries and tap houses I found within a mile of a trail marked on the Miami Valley Trails Map. I sorted by trail number, followed by towns from south to north, then by brewery in alphabetical order. I measured them on Google Maps, so distances are approximate. I might have missed a few. Also, I mainly kept within the region that I cover in Dayton Beer. Go here to find more breweries near Miami Valley trails.

Enjoy your ride and your beer, and as always, stay safe.Brewpubs and tap houses near Miami Valley trails1. Ohio-to-Erie Trail (Xenia-east)Xenia

Devil Wind Brewing, 130 S. Detroit St.: 1,300 ft. N

2. Creekside Trail (Xenia-west)

Xenia

Devil Wind, 130 S Detroit St.: 1,600 ft. NE 3. Little Miami Scenic Trail (Xenia-Springfield)

Xenia

Devil Wind, 130 S. Detroit St.: on bike laneYellow Springs

Yellow Springs Brewery, 305 N Walnut St.: on trailSpringfield

Mother Stewart’s Brewing, 109 W. North St.: 2,300 ft. N3. Simon Kenton Trail (Springfield-north)

Springfield

Mother Stewart’s, 109 W. North St.: 2,300 ft. NBellefontaine

Brewfontaine, 211 S. Main St.: 4,200 ft. NE4. Xenia-Jamestown Connector

Xenia

Devil Wind, 130 S. Detroit St.: 1,300 ft. N5. Wright Brothers-Huffman Prairie Trail

Fairborn-Beavercreek

Wandering Griffin, 3725 Presidential Drive: 1 mi. S8. Mad River Trail

Dayton

Barrel House, 417 E. Third St.: 2,500 ft. SDayton Beer Co., 41 Madison St.: 2,200 ft. SFifth Street Brewpub, 1600 E. Fifth St.: 1 mi. SLock 27 Brewing, 329 E. First St. rear: 1,100 ft. SMudlick Tap House, 135 E. Second St.: 1,100 ft. SToxic Brew Co., 431 E Fifth St.: 3,700 ft. SWarped Wing Brewing, 26 Wyandot St.: 2,300 ft. S19. Dayton-Kettering Connector

Dayton

Barrel House, 417 E. Third St.: 700 ft. E.Dayton Beer, 41 Madison St.: 1,000 ft. EFifth Street Brewpub, 1,600 E. Fifth St.: 4,900 ft. ELock 27, 329 E. First St. rear: 1,000 ft. EMudlick Tap House, 135 E. Second St.: Half a block WToxic Brew, 431 E. Fifth St.: 1,500 ft. E.Warped Wing, 26 Wyandot St.: 700 ft. EKettering

Eudora Brewing, 3022 Wilmington: 3,100 ft. E25. Great Miami River Trail

Miamisburg

Lucky Star Brewery and Cantina, 219 S. Second St.:, 1,200 ft. EStar City Brewing, 319 S. Second St.: 1,600 ft. E.Dayton

Barrel House, 417 E. Third St.: 1,700 ft. SCarillon Brewing Co., 1000 Carillon Blvd: 800 ft. SDayton Beer, 41 Madison St.: 2,400 ft. SLock 27, 329 E. First St., rear: 1,600 ft. SMudlick Tap House, 135 E. Second St.: 2,300 ft. SToxic Brew, 431 E. Fifth St.: 4,400 ft. SWarped Wing, 26 Wyandot St.: 3,000 ft. STroy

Tabernacle Brewing (Moeller, opening summer 2019,) 214 W. Main St.: 2,100 feet S40. Buck Creek Trail

Springfield

Mother Stewart’s, 109 W. North St.: 1,600 ft S (across bridge)

Dayton Beer: A History of Brewing in the Miami Valley is scheduled for release July 22, but you can pre-order it now on Amazon.com.

Published on May 06, 2019 03:13

April 29, 2019

The Rose that took Ohio counties dry

Carl Schnell's brewery in Piqua, circa 1900. Source: Piqua Public Library.

Carl Schnell's brewery in Piqua, circa 1900. Source: Piqua Public Library.© 2019 Timothy R. Gaffney

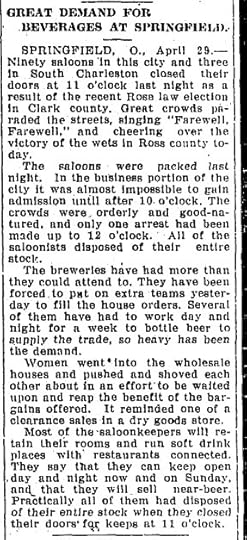

The 18th Amendment poised America for Prohibition 100 years ago. But prohibition was old news for Ohio by then. The drive to ban beer and booze swept the state a decade earlier.

On Feb. 26, 1908, The Ohio legislature passed the Rose Law, introduced by Ohio Sen. Isaiah Rose (1843-1916.) The Republican from Marietta was a farmer, a Civil War veteran and the great-great-great grandfather of singer Kelly Clarkson. More to the point, he was a champion of the temperance movement, and his namesake bill allowed voters to petition their counties for special elections to ban the sale of alcoholic beverages. In the ensuing months a majority of Ohio counties voted to go “dry.”

Dayton Daily News, April 29, 1909, page 3Tabulations showed rural voters tended to favor going dry while city-dwellers tended to want to stay “wet.” For example, a large urban core in Dayton kept Montgomery County wet, while Clark County's rural voters took the county dry by a slight margin over Springfield’s wet majority.

Dayton Daily News, April 29, 1909, page 3Tabulations showed rural voters tended to favor going dry while city-dwellers tended to want to stay “wet.” For example, a large urban core in Dayton kept Montgomery County wet, while Clark County's rural voters took the county dry by a slight margin over Springfield’s wet majority.But the local option law worked both ways. In April 1912, thirsty Clark County voters petitioned for another special election and overturned the earlier dry vote.

“The wets” argued that going dry “had robbed (Springfield) of thousands of dollars in revenue, while the bootlegger and the speak-easies flourished,” the Dayton Daily News reported on April 26. After losing by 139 votes in 1909, the “wets” won in 1912 by 2,016 votes, the News reported.

The victors celebrated. “The wets are parading the streets, headed by a band,” the paper reported. But a few sought to settle grievances: A mob of “jubilant wets” smashed windows at the home of Oran F. Hypes, a former state senator and local temperance leader.

Ohio voters repealed the Rose Law in November 1914 by approving a “home rule” amendment to the state constitution. Dry counties became wet again. Saloons reopened.

But the reprieve came too late for two breweries in Miami County, where a special election in November 1908 took the county dry. While the law went into effect on Dec. 24, the impact came even quicker.

“The saloons of Piqua and Miami County are not waiting until the limit of time to close… but are closing now,” the Dayton Daily News reported on Dec. 10, 1908. “Four have already closed in Piqua and seven in the county.”

From 'Governor Johnson Addresses Piquads,' Dayton Daily News, Dec. 10, 1908, page 10.

From 'Governor Johnson Addresses Piquads,' Dayton Daily News, Dec. 10, 1908, page 10.The next month, workers in the Schnell Brewery, on the east side of the Great Miami River, rolled out barrels of beer and lined them up on the river bank just north of the Ash Street Bridge. It was brewer Carl Schnell’s entire stock—anywhere from 40 to 135 barrels, according to differing reports in the January 23 News and the February Western Brewer.

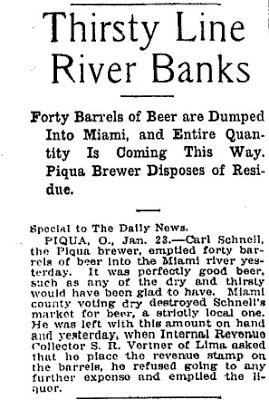

Schnell ordered the workers to empty the barrels into the river. He had chosen to dump his stock rather than pay federal revenue taxes on it. “Miami County voting dry destroyed Schnell's market for beer, a strictly local one,” the News reported.

Dayton Daily News, Jan. 23, 1909, page 5.

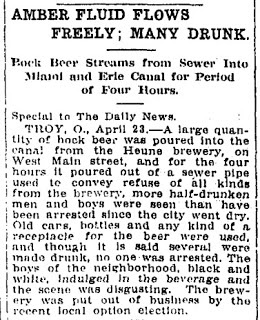

Dayton Daily News, Jan. 23, 1909, page 5.A livelier scene played out three months later in Troy, when beer began splashing into the Miami and Erie Canal from the Henne Brewery's sewer pipe. As word of the discharge spread, many adults and even some youngsters scrambled for old cans, bottles or any handy vessel.

“For the four hours it poured out of a sewer pipe used to convey refuse of all kinds from the brewery, more half-drunken men and boys were seen than have been arrested since the city went dry,” the News reported on April 23.

Dayton Daily News, April 23, 1909, page 19

Dayton Daily News, April 23, 1909, page 19The Rose Law was short-lived, but some of its effects were permanent. Neither brewery opened again.

Read more about the impact of temperance and Prohibition in Dayton Beer: A History of Brewing in the Miami Valley. Its release date is July 22, but you can pre-order it now at Amazon.com.

Published on April 29, 2019 03:21

April 22, 2019

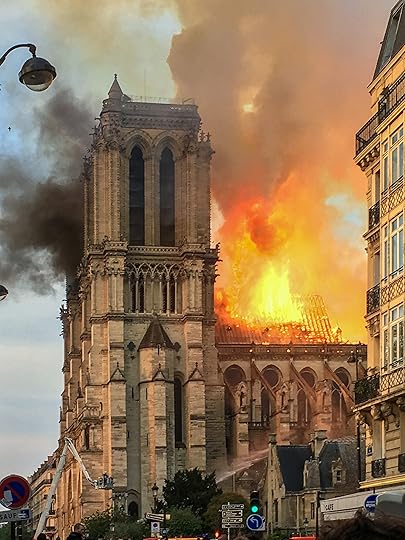

Notre Dame, breweries tell us history is fragile

Notre Dame burning on April 15. Photo: LeLaisserPasserA38 [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...)

Notre Dame burning on April 15. Photo: LeLaisserPasserA38 [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...)The flames that erupted through the roof of the majestic Notre Dame de Paris last week gave us a shocking reminder of the fragile nature of history.

Architecture is a part of the record of our existence on earth. Old buildings tell us what times were like in our communities and around the world before we came. They're like postcards from the past.

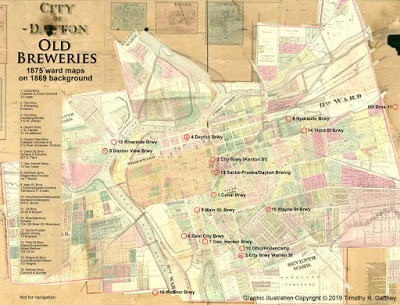

When it comes to breweries, a lot of those postcards are missing. When I researched Dayton Beer: A History of Brewing in the Miami Valley, I wanted to locate as many original breweries as I could. Dayton itself had so many I had to make a map to help me keep track of them.

Map of old Dayton breweries. Composite graphic by Timothy R. Gaffney, with 1875 and 1869 maps.

Map of old Dayton breweries. Composite graphic by Timothy R. Gaffney, with 1875 and 1869 maps.But when I went looking for them, I found very few still standing. In most cases, newer buildings, parks or parking lots had replaced them. Some had burned. Some had been torn down. Those that survived were masquerading as other kinds of buildings, their histories generally unknown.

Sachs-Pruden brewery in Dayton. Photo by Timothy R. Gaffney

Sachs-Pruden brewery in Dayton. Photo by Timothy R. GaffneyA rare exception is the former Sachs-Pruden brewery at 120 S. Patterson Blvd. Edward Sachs (1851-1901) and David Pruden (1855-1910) built it with great expectations, commissioning the prominent Dayton architectural firm Peters and Burns (later Peters, Burns & Pretzinger) and pouring $150,000 into its construction, according to an 1893 Dayton Daily News report. It towered over the canal where South Patterson now runs and featured a 300-barrel brew kettle.

But its business failed after a few years. The Lowe Brothers Paint Company bought it in 1920, and later the Hauer family restored it for use as a music store. It's now the Dayton Metro Library's administration center.

Remaining building of the Olt Brothers brewery on N. McGee Street. Photo by Timothy R. Gaffney

Remaining building of the Olt Brothers brewery on N. McGee Street. Photo by Timothy R. GaffneyA long. two-story building with an ornate facade at the southwest corner of Second and McGee is a former horse stable of the Olt Brothers brewery. Incorporated in 1906, it brewed until 1940, surviving prohibition with dairy products and Polar Distilled Water. In 2018, Warped Wing Brewing revived its once-popular Superba brand with a hoppy pilsner of the same name.

Two counties north, I found another old brewery hiding in plain sight.

Part of the Wagner brewery in Sidney, Shelby County. Photo by Timothy R. Gaffney

Part of the Wagner brewery in Sidney, Shelby County. Photo by Timothy R. GaffneyOn Poplar Street close to the Great Miami River, what remains of the once-prominent John Wagner Sons Brewing Co. lurks undercover as a storage building for Sidney Public Schools. Sidney was once famous for its Wagner cooking ware, but a branch of the Wagner family also operated a brewery there from as early as 1850. The brewery prospered until the early 1900s.

It isn't the brewery but another structure that testifies to the wealth that brewing once generated in Sidney.

John Wagner House in Sidney. Photo by Timothy R. Gaffney

John Wagner House in Sidney. Photo by Timothy R. GaffneyUp the street from the brewery site stands the home of John Wagner (1834-188,) built in the 1860s with money from Wagner's brewery. It's now the home of the Aspen Family Center, which has preserved the house's Victorian splendor.

Hollencamp House in Xenia. Photo by Timothy R. Gaffney

Hollencamp House in Xenia. Photo by Timothy R. GaffneyIn Xenia, meanwhile, the Hollencamp brewery is long gone. Its only reminder the once-opulent house at 339 E. 2nd St., built on the north side of the brewery by Bernard Hollencamp (1913-1872.) While the house earned inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places, it's now boarded up and in decay. It's a sad, tattered postcard from the Miami Valley's brewing past—still salvageable, but sliding quietly toward oblivion.

You'll find more stories about the Miami Valley's old breweries and their brewers in my book. Pre-order it now at Amazon.com.

Published on April 22, 2019 03:01

April 15, 2019

Black holes, gravity wells and... beer?

A black hole. Event Horizon Telescope image, courtesy National Science Foundation.

A black hole. Event Horizon Telescope image, courtesy National Science Foundation.© 2019 Timothy R. Gaffney

Astronomers made headlines last week when they released the first-ever picture of a black hole—an unimaginably weird place with a gravitational field so strong nothing that falls into it can escape—not even light.

What does that have to do with beer? Um, well, nothing. But, strangely enough, it has a lot to do with my book.

One way to think of a black hole and its gravitational field is as a hole in the bottom of a funnel-shaped well—a gravity well.

“Gravity well” was a term I learned as a teen when I read Arthur C. Clarke’s The Promise of Space —a non-fiction book the great science fiction writer published in 1968 as a kind of companion to his novel (and the film) 2001: A Space Odyssey . Every planet, moon and chunk of rock has its own “gravity well,” where its gravitational field can influence other objects.

The concept popped back into my mind in 2017 as I was trying to map out the area to cover in my book.

My publisher wanted the title to be “Dayton Beer,” following the style of its other books about brewing history in cities across the United States. It begged the question: What’s Dayton?

It wouldn’t make sense to write a book that only examined brewing history within Dayton’s corporate boundaries. City limits have little to do with how people live or what we consider local. More to the point, where was the potential audience for this book?

I reasoned it was in places where local craft breweries were thriving. If people like local beer, they just might want to learn a little about their local beer history. So, I decided “Dayton Beer” would encompass a region. Fine, but… what region?

For help, I turned to Google Maps and searched for breweries near Dayton.

A pattern immediately appeared. Numerous breweries surrounded Dayton like satellites orbiting a planet. Crooked Handle Brewing in Springboro seemed to define the southern edge of this region, while Hairless Hare marked the northern edge. Devil Wind in Xenia and Yellow Springs Brewery formed an eastern boundary in Greene County.

But I knew Google Maps wasn’t showing me every brewery. I turned to the Ohio Craft Brewers Association’s website. There, a map of craft breweries gave me a clearer picture. It showed a pattern of craft breweries gathered in clusters around metropolitan areas.

The clusters looked familiar. They looked like… yes, gravity wells. Dayton had its own distinct gravity well of breweries. Mother Stewart’s and Pinups and Pints in Clark County were off to the northeast, but closer to Dayton than anywhere else. The same was true of Moeller Brew Barn and Tailspin Brewing Co., far to the northwest in Mercer County.

This pattern made sense to me. It reflected the historical pattern of breweries that appeared as settlers moved up the Miami Valley and built communities. It also—I hoped—showed me where I would be likely to find the most readers. (The valley extends down to Cincinnati, of course, but its brewing history is already the subject of several books.)

So, this is the area you will find covered in Dayton Beer. And it’s why I added the subtitle, “A History of Brewing in the Miami Valley.”

Was I right? Will my book find its proper orbit in Dayton’s gravity well? Or will it spiral irreversibly into the proverbial black hole of literature?

Maybe I should get some expert advice. Hey, HAL… can I buy you a beer?

Published on April 15, 2019 03:32

April 8, 2019

Miami Valley's small breweries then and now

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 18.0px Calibri} p.p2 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 18.0px Calibri; min-height: 22.0px} p.p3 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 18.0px Calibri; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000} p.p4 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 18.0px Calibri; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000; min-height: 22.0px} span.s1 {-webkit-text-stroke: 0px #000000} span.s2 {font-kerning: none}

Infographic: "The Illusion of Choice," by Jeff Desjardins, visualcapitalist.com.

Infographic: "The Illusion of Choice," by Jeff Desjardins, visualcapitalist.com.© Copyright 2019 Timothy R. Gaffney

A 2016 infographic titled “The Illusion of Choice,” by Jeff Desjardins at the Visual Capitalist, shows how a handful of megabrewers own most of the myriad brands you find on supermarket shelves.

In my research for Dayton Beer , I learned this trend was much older and deeper than I’d ever considered, and I saw how it transformed the brewing scene in the Miami Valley.

Well before Prohibition smashed the brewing industry a century ago, the trend in the beer business was one of mergers and takeovers. For example, by the late 19th century, English investment groups were on the hunt for hometown American breweries they could buy up and consolidate for greater profits. That’s how Springfield’s two local breweries became one company, the Springfield Breweries, in 1890.

The turn of the 20th Century found local brewers in cities nationwide forming combines in the face of growing competition from national brands. Here, a half-dozen Dayton brewers merged as the Dayton Breweries Co. in 1904.

But this decade has seen small craft breweries proliferate and thrive. Changes in consumer demand and state laws have dramatically reshaped the market, as Derek Thompson wrote last year in The Atlantic .

Tailspin Brewing Co. in Coldwater, Ohio. Photo by Timothy R. Gaffney

Tailspin Brewing Co. in Coldwater, Ohio. Photo by Timothy R. GaffneyCan a brewery be too small? I'm not a business expert, but so far, the craft brewery marketplace seems to have enough space for local breweries to grow without crowding out smaller ones. And I've seen tiny breweries sustaining themselves themselves in very different business environments.

A couple of examples are the Heavier than Air Brewing Co., located in the suburban Normandy Square Shopping Center in Washington Twp. near Centerviile, and the Tailspin Brewing Co. in the rural village of Coldwater in Mercer County. Both are tiny microbreweries that seem to have found niches in very different circumstances.

Opened in 2017, Heavier than Air is a small, storefront brewpub with its brewery and taproom sharing 2,000 square feet in a suburban shopping center. It’s managed to survive its first year despite being surrounded by bars, pubs and restaurants.

Tailspin’s situation is just the opposite: it’s located deep in Ohio farm country west of Grand Lake. Started in 2015 by a retired Air Force fighter pilot, it occupies a picturesque, repurposed dairy barn on the edge of town.

Coldwater’s population was only about 4,400 in 2010, according to Wikipedia, but founder-owner Jack Waite deliberately planned small: Tailspin's capacity is only 700 barrels per year, he told me last year. And Waite is located in the heart of the “Land of the Cross-Tipped Churches,” a region that strongly reflects the heritage of its German settlers.

“If I can’t sell a beer here, I’m doing something wrong,” he said.

A century or more ago, microbreweries were common in small communities across the Miami Valley. Many fell victim to the pre-Prohibition temperance movement—especially a 1908 Ohio law that allowed “dry votes” to ban the sales of alcoholic beverages at the county level.

I found records of breweries existing for years in communities far smaller and more isolated than Coldwater—but they, too, faced challenges. Here are two examples I found.

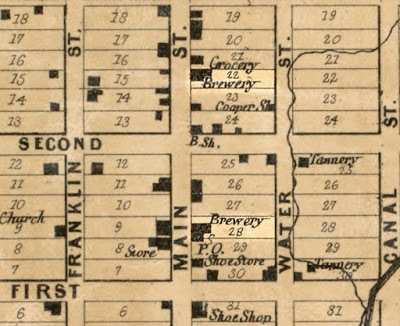

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; line-height: 13.0px; font: 14.0px Times; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000} span.s1 {font-kerning: none} 1860s map of Auglaize County shows two breweries in New Bremen.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; line-height: 13.0px; font: 14.0px Times; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000} span.s1 {font-kerning: none} 1860s map of Auglaize County shows two breweries in New Bremen.New Bremen is a small village of about 3,100 people in Auglaize County, 13 miles southwest of Wapakoneta. Its population was only about 2,000 in 1875, according to a state directory. But an 1860s map of Auglaize County marked two New Bremen breweries just a block apart, straddling Second Street on the east side of North Main. Records indicate saloons also operated at both locations, so the breweries might simply have been supplying their own establishments.

Were they too small to survive? Land records saw a succession of owners for both properties over the second half of the 1800s. The brewery north of Second turned out 425 barrels in 1870, according to an industrial census taken that year. By 1878, under different owners, production had dropped to 320 barrels. The other brewery was of a similar size.

By the 1870s, they must have started feeling pressure from a new brewery just four miles away in Minster—the Star Brewery, whose Wooden Shoe beer would become legendary. Both New Bremen breweries appear to have ceased production by 1880.

Remoteness might have been a blessing for very small breweries.

Tiny New Madison in Darke County lies 30 miles northwest of Dayton and 13 miles northeast of Richmond, Ind. Home to about 900 people today, it was half that size in 1870, yet it already supported a brewery.

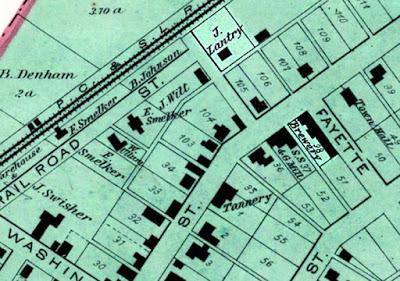

1875 map of Darke County shows brewery in New Madison.

1875 map of Darke County shows brewery in New Madison.John Lantry, an Irish immigrant, built New Madison's brewery in 1858 and expanded it several times. By the 1870s, it stretched 144 feet down the west side of Fayette Street from Main. Lantry billed himself as “Manufacturer of Ale and Beer,” and his products were “guaranteed to be of the latest style and to give entire satisfaction,” according to an 1866 newspaper ad.

The brewery seemed to prosper: census records show the property's value grew from $300 to $10,000 between 1860 and 1870. But Lantry’s health failed. He closed the brewery in 1875 after a run of 27 years.

“Mr. Lantry is disabled so that he seldom leaves the premises,” W. H. McIntosh wrote in The History of Darke County , published in 1880. The census that same year described Lantry's illness as “rheumatism”—a rheumatic disorder that could have painfully afflicted his joints, eventually disabling him.

Land and census records indicate Lantry was a sole proprietor with no children to carry on the business. Evidently, Lantry found no one else with the interest, capital or skills to take it over. As far as I could learn, the brewery never reopened.

Read more about these breweries and others that once dotted the region in my upcoming book, Dayton Beer: a History of Brewing in the Miami Valley (Arcadia/The History Press, July/August 2019.) Meanwhile, do you have a brewery story of your own? Share it!

Published on April 08, 2019 03:39