Jacke Wilson's Blog, page 83

April 18, 2014

A History of Jacke in 100 Objects: #2 – The Dynamints Box

I was five but remember it like yesterday. How my big sister and I were in our driveway, riding her new Kick-N-Go, and the cool kid who lived up the street came racing toward us on his bike. He had never come to play with us before; I thought maybe he was planning to ask for a ride on the exciting new Kick-N-Go, the first in our neighborhood. Good lord, that thing was cool. Self-propelled, with a handbrake. Just look at these beauties:

The only reason they’re not around now is that they’re a terrible product that are impossible to ride well, but we didn’t know that then. We just figured we were kids who hadn’t figured it out yet.

That’s the thing about being a kid. You’ve got a lot of figuring out to do.

So in rode Joel, the cool kid from up the street. It was a thrill: he was a year older than me and had sideburns and a stepbrother in high school who lived in a room over their garage. Big stuff for me at that time, who was mostly stuck with my sister and her friends. I worshiped my sister, and her friends were mostly nice to me, but it wasn’t the same. Joel could beat kids up, except he was too cool to ever need to. He reminded me of a Hardy Boy:

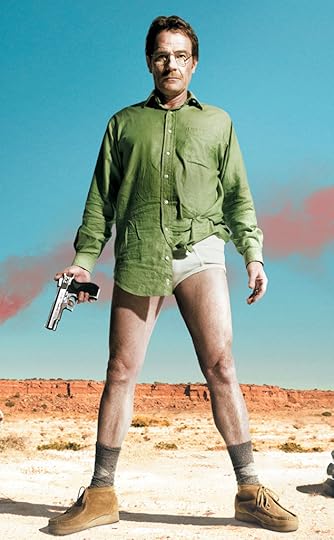

No, he was cooler than that and rode alone. More like this guy:

Supercool Joel barely noticed the Kick-N-Go. He zoomed right past us and into our garage, his younger sister Tina trailing behind. As soon as my sister and I recovered our senses and joined him, he went to the step that led to the back door of our house and pressed the garage door button. The automatic door chugged down. The four of us were now alone in near darkness in our garage.

I had no idea what was going on.

He murmured something to my sister. The two of them appeared to reach some kind of understanding. Suddenly they bolted out the back door of our garage, and then the four of us were sprinting across our backyard and behind our neighbor’s house.

Now we were trespassing. I still had no idea what was going on. My heart was pounding so hard my ribs hurt.

At the corner of the house, Joel stuck his arm up the downspout and fished something out. It was a plastic Dynamints box, with a white lid and a faded label, and it didn’t have any mints, just a single sheet of notebook paper, folded and crammed inside. He surrendered it to my sister, who removed the paper and unfolded it as we gathered around and peered over her shoulder.

The handwriting was printed with a red pen, childlike but decisive:

A bucket of water we will throw on her head.

Tina and I looked at each other and gasped. My sister’s mouth was set tight.

It was 1977, and we were at war.

#

A bucket of water we will throw on her head.

Who was the target of this nefarious plot? My sister, Ellen.

And the perpetrator? I could guess right away. It was our across-the-street neighbor. My sister’s oldest friend.

Ginny.

Ginny and Ellen had a history. They had been born weeks apart and had grown up together, thrown together by neighborhood proximity in spite of not having anything in common. Fights were frequent, but nothing had ever broken the bond they shared. They were like sisters.

But even for them, this was unusual. A sinister plot, written down and hidden in a rainspout? Escalating violence? Conspiracies?

And Ginny had enlisted other people in this battle?

I hadn’t known that any of this was happening. Now it felt like I was in way over my head.

Ellen explained that Ginny had declared that she “hated” Ellen. Ellen hadn’t retaliated, but Ginny was hell-bent on battle.

I believed Ellen because I had seen the dynamic in action, many times. Ellen was popular at school, and got good grades, and was a favorite of her teachers; Ginny struggled with all these things. Ginny took it hard whenever Ellen had a success: a spelling bee victory, a choice part in the Christmas pageant, an election to student council.

It was not as if Ginny was always the runner-up. Ellen was the best, but Ginny was not second-best, or third-best, or anything close. She wasn’t even part of the conversation.

At my church there was a picture of the Last Supper. Jesus was speaking, looking at the heavens, as eleven of the disciples gaze at him with wonder. Only Judas looks away, stares directly at the viewer, wearing a venomous expression. I always pictured Ginny as taking that posture in the classroom: lurking in the back of the room, hunched over, snarling as Ellen stood up front, a halo behind her head, winning prize after prize after prize.

It was not good to be Ginny.

#

I had not realized it, but I had been there when the war had begun.

We were playing at our house, as we usually did because Ginny’s father Frank worked the night shift at the GM plant. My memory of him is coming to the door, angry that a doorbell had rung but softening when he saw it was Ellen, because he thought she had a positive influence on his daughter.

Frank suffered from a disease that impaired his ability to walk—another thing I didn’t fully understand. All I knew was that I didn’t like going over there, with the constant reminders to keep our voices down, either because “Frank’s trying to sleep” or “Frank’s legs are bothering him.”

Thinking of him now, I can only feel pity for how hard his life must have been, but back then I didn’t understand. Why did he sleep during the day? And why did he have so much trouble walking? Why was he so big, and so angry? He made me feel like I did when I saw on television a creature that transformed into a monster at night, a vampire or a wolfman, something not quite human.

So there we were, Ellen, Ginny, and me, spending a rainy day playing school in our basement. My parents had installed two blackboards that our town’s school had discarded, and Ellen and Ginny were standing across the room from each other, each of them teaching their own imaginary class.

I was in Ellen’s class, sitting cross-legged on the rug, learning addition and subtraction as Ginny taught spelling to a row of stuffed animals.

“Class,” Ginny said, “This is how we spell please.”

Ellen looked at Ginny’s blackboard and frowned. “Ginny,” she said gently. “You might want to take another look at that.”

Scowling, Ginny looked at the blackboard. I looked too. She had not written please. She had written pasel.

“Class,” Ginny said more loudly. “I’m sorry we were interrupted. Please write the word please fifty times. You can copy it from the blackboard, where it is written correctly.”

Looking back, I wonder if Ginny may have been dyslexic. It was not something Ellen or I were equipped to understand at that age. Ellen was just trying to be helpful. She had to be helpful, just like she had to be good. She knew no other way. It was why I and everyone else admired her so much. Everyone, that is, except Ginny.

Ellen was quiet for a while. She knew she shouldn’t say anything. But she just couldn’t help herself. Ginny needed to know the right way to spell please. It was important.

“Do you want to borrow Jacke for a minute, Ginny?” Ellen said sweetly. “He could visit your class.”

“Why would I want to do that?” Ginny asked. “He’s your student.”

“Because…” Ellen said, flustered. “Because Jacke knows how to spell please.”

“Class,” Ginny screamed. “I need to close the door!” She stomped to the edge of the rug and slammed an imaginary door. “Too many annoying interruptions! I will speak to the principal about this tomorrow! Some other teachers may need to be fired.”

Ellen sighed and went back to the numbers on her blackboard. Please would be pasel, at least for today. Ginny would need to learn the hard way, as always.

I tried to pay attention but was too afraid. Ginny would often pinch my arm or poke me in the ribs when Ellen wasn’t looking. I didn’t want to turn my back on her.

But Ginny had other plans.

“Class,” she announced. “Spelling is over! It’s time for the Christmas pageant. Time for me to assign parts.”

Ellen stopped writing.

“Danny,” Ginny continued, “you can be Joseph. Little Ginny, because you are the best student in the class, you will be Mary.”

She paused for effect.

“And Little Ellen, you will be the king who tried to kill the baby Jesus.”

Ellen, who had lived with this from Ginny for her entire eight years, was nevertheless shocked. She set the chalk down and folded her arms across her chest. She shook her head sadly—sadder for Ginny, I thought, than she was for herself. It was typical of Ellen: insults didn’t bother her so much as knowing that the person delivering the insult was expressing their own pain. She was a wise kid.

And maybe this pity was what put Ginny over the edge. She stared at Ellen, her face turning redder and redder, until finally she took off, running up the steps and across the street to her house. My mother shrugged and closed the front door, which Ginny had left wide open, her usual way of departing.

Later that day, Ellen and I were riding our bikes down the block to get to the ice cream truck before it turned the corner onto a busier street. We passed Joel and Tina’s house. Ginny was there, whispering to the two siblings. As we passed by, they stopped and stared at Ellen. Ginny was smiling falsely, and all three of them had a strange look in their eyes. It looked to me like hatred or evil.

The war had begun.

#

Back in the garage, Ellen thanked Joel for letting her know about the note. Joel smiled and hopped on his bike and took off for the Spring, a very cool destination on the outskirts of town, past the trailer park, that was farther than I was allowed to go without my parents. I walked to the end of the driveway and watched my hero leave.

Ellen went inside. She took the note with her, evidence that might someday help her explain to my parents what kind of war was being waged against her. I was left behind with a brand new playmate, Tina, and the empty Dynamints box.

It pleased me to be suddenly in possession of a cool new thing. Grownups would toss this in the trash without a second thought, but what did they know? We had all kinds of toys made out of stuff like this. Coffee cans or Pringles cans (with masking tape around the sharp edges) were a good way to store stuff. Egg cartons. Pipe cleaners. Toothbrush handles. Scraps of wood. Binder twine. Stuff like this was valuable because it could be used to make other stuff.

Tina and I sat down on the oily cardboard that garages in the ’70s had because cars leaked like crazy. I unsnapped the plastic lid and sniffed inside. Wintergreen and ink, a not unpleasant combination. The fumes opened my nostrils and clarified my thinking. A kindergarten high. (What can I say? It was the ’70s.)

Tina took a turn and passed it back. We smiled at each other. What we had just shared was as exciting to my five-year-old brain as if we had just kissed on the mouth.

Tina had other thoughts.

“We need to get her,” she said. “We need to get Ginny.”

I was confused but captivated. Tina was six months younger than me—more like one of my peers than my sister’s friends. (Two and a half years older, which made them from a completely different generation. They may as well have been my aunts.) And she was so, so, so cute. I didn’t know how to deal with any of this.

The garage was dark. Without Joel and Ellen there, I was free to fall under Tina’s spell.

“Yes,” I heard myself say. “We need to do that.”

I have no idea why I said this. Maybe it was because Ellen and Ginny were only in second grade, but already it was clear that Ellen had a lot more to lose than Ginny. Ginny was already viewed as a bad kid. She could act as malevolent as she wanted and no one would be surprised or disappointed.

That didn’t seem fair to Ellen, who couldn’t fight back. And now, here was Tina, who had actually been on the other side. She knew the extent of the evil that lurked over there, across the street. She knew what justice required.

Like Joel, she seemed to know exactly where everything was in our garage. (The fact that all the houses on our street looked the same may have had something to do with that, but I hadn’t figured that out yet.) She rose from the step and went straight to a box where my dad stored an old clothesline he was keeping around as a spare.

She held up the coil.

“With this,” she said, her eyes gleaming.

I didn’t know what she was going to do. But I could not bring myself to resist.

#

A minute later we were in position: Tina was kneeling between two shrubs at the side of their front porch; I was installed behind a tree on the other side of their driveway. Each of us held one end of the clothesline.

A trip line! This was serious stuff. I had to believe that Ginny had planned to pull this very trick on Ellen. It seemed far too devious for cute, young Tina to come up with something this demonic on her own.

A bucket of water we will throw on her head.

A clothesline we will trip her with.

We practiced holding the line two inches off the ground, perfect for tripping Ginny or wiping her out if she happened to arrive on her bike. As I settled in to wait, Tina suddenly jerked her arm, pulling up her end of the line.

Her half of the line was now neck high. I looked at Tina helplessly, too scared to speak. She read it in my eyes: The neck? Really?

She smiled and nodded. My heart was pounding.

I lifted my arm too. The neck. We were going for the neck.

It was all there for me, the future all laid out. We would wipe out Ginny, then skedaddle home like the Dukes of Hazzard. We’d lock ourselves in the garage—just me and Tina, together in the dark!—and huff the Dynamints box and giggle at how we had thwarted my sister’s sworn enemy. It would be delicious.

We jerked the line up and down a few times for practice. Tina laughed. It sounded like a cackle. I laughed too.

And then I looked at the street. What I saw almost made me pee my pants.

Someone had turned up the driveway. They were coming straight toward us, close and getting closer. But it was not Ginny.

It was her father Frank.

#

He was walking heavily, as usual. The doctor had put him on this regimen, prescribing one trip around the block each night before he headed off to the second shift. Frank did his best to comply, though it was obviously painful. Stooped over, shuffling, slow, head down, breathing heavily.

I dropped my end of the line. Tina looked at me with alarm.

Pick it up, she mouthed, pointing at the cord. Do it.

This was our plan? To trip Frank? A grownup? I looked at Frank, who had not seen us. I looked at Tina. Frank again, walking like a wounded bear. Tina, my five-year-old femme fatale.

I picked up my end.

Frank grunted. He hadn’t noticed us or the clothesline, two inches off the ground.

Across the driveway, Tina stood up and raised her arm as high as it would go. Her eyes implored me to do the same.

I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. She was going for his neck.

Frank was only steps away. Head still down. Shuffling closer. I could smell him now: newspapers and engine oil and cardboard and grease. A walking garage.

Suddenly I lost my nerve. I threw down my side of the cord and took off. Tina did the same.

Frank paused as we ran past him, pounded our way across the street, and retreated to my garage. Breathing hard, standing next to Tina, I was relieved that the worst was over. The clothesline lay feebly on the driveway.

We would have to come up with some excuse for what it was doing there. Playing house and planning to hang up clothes? It was all I could think of. Maybe I needed to soak something with the hose that I could claim I was planning to dry.

But it was over, oh thank god it was over. Tina smiled at me: we had come close to doing it! She didn’t hate me! I couldn’t believe how good it felt to earn her approval, even though I had chickened out. We had almost done it and hadn’t gotten into trouble!

As we laughed, exhilarated, Frank bent down to pick up the cord. His foot somehow got twisted. He tried to unwrap the line but went the wrong way around, tangling himself further. Then the rope got hooked on his wrist somehow, and his knee, and suddenly he was doing a slow, awkward pirouette, like a dumb animal in a net, unable to figure out what was happening or how to escape.

I opened my mouth. No sound emerged.

He turned again and staggered. He was completely bound now, tied up like something about to be slaughtered, flailing around but only making things worse. Finally, with cords wrapped all around his arms and legs and shoulders and belly, he leaned, stumbled back, spun halfway around, and pitched forward face first, hitting the cement with a horrible slapping sound we could hear all the way across the street.

He lay there and groaned. He didn’t sound like a monster. He sounded like an old man about to die.

#

Illness is a terrible thing. A kid doesn’t understand it any better than anyone else. I only knew that I had caused something awful to happen to someone who was sick, which meant I was bound to get in a lot of trouble. I burst into tears. Tina jumped on her bike and pedaled home, leaving me alone.

Ellen came running out. “What’s going on?” she said. “What did you do?”

I shook my head, bawling.

She glanced across the street. “Mom!” she shouted. “Frank needs help!”

My mom emerged from the door and the two of them ran across the street to untie Frank. My mom touched his forehead, several times. He held one of his shoulders and swung his arm gingerly, as if it were broken. Finally Ginny’s mom came out and helped him into the house.

My mom picked up the clothesline. She looked confused. She did not seem to have any idea what had happened.

Ellen, of course, figured it out right away. She shook her head as the two of them walked toward me. I cried harder.

Watching them approach, I cried because I had figured something out.

While Ellen had been in the house, helping my mother, doing the right thing, I had been in the garage, seduced by the smell of the Dynamints and the thrill of doing whatever a dangerously cute little girl wanted me to do.

I cried because I was not good like my sister. I was not Ellen and I never would be.

I was Ginny.

—

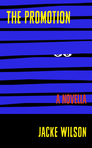

Ugh, this one dug a little deep. But there you go, readers. Anything for you. You can read about another grown man falling down in Object #1, which tells the story of a disastrous football team and a coach at the end of his rope, or the end of his bolt cutter, or something. Oh yes, we have plenty of posts on failure here at the Jacke Blog, including this one about the great Penelope Fitzgerald. And of course, if you’re truly looking to get in touch with your “intrigue and deadpan comedy” side, with lots and lots of failure thrown in for good measure, The Promotion and The Race are there waiting for you for less than five bucks (and the e-reader/smartphone versions even less than that). I also have free review copies for all my friends—shoot me an email and I’ll shoot you a copy!)

April 17, 2014

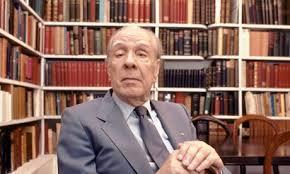

Borges on Fiction and Philosophy

Image Credit: guardia.co.uk

Borges on fiction and philosophy? You could devote an entire blog just to this subject, of course. But for today, I’ll focus on this interview from 1976, which is full of gems.

Interviewer: Can a narrative, especially a short narrative, be rigorous in a philosophical sense?

Borges: I suppose it could be. Of course, in that case it would be a parable. I remember when I read a biography of Oscar Wilde by Hesketh Pearson. Then there was a long discussion going on about predestination and free will. And he asked Wilde what he made of free will. Then he answered in a story. The story seemed somewhat irrelevant, but it wasn’t. He said – yes, yes, yes, some nails, pins, and needles lived in the neighborhood of a magnet, and one of them said, ‘I think we should pay a visit to the magnet.’ And the other said, ‘I think it is our duty to visit the magnet.’ The other said, ‘This must be done right now. No delay can be allowed.’ Then when they were saying those things, without being aware of it, they were all rushing towards the magnet, who smiled because he knew that they were coming to visit him. You can imagine a magnet smiling. You see, there Wilde gave his opinion, and his opinion was that we think we are free agents, but of course we’re not.

Borges’ spoken words are a lot like his writing: concise, dreamy, and packed with ideas.

Interviewer: Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius is a good example of one of your stories where, however the story ends, the reader is encouraged to continue applying your ideas.

Borges: Well, I hope so. But I wonder if they are my ideas. Because really I am not a thinker. I have used the philosophers’ ideas for my own private literary purposes, but I don’t think that I’m a thinker. I suppose that my thinking has been done for me by Berkeley, by Hume, by Schopenhauer, by Mauthner perhaps.

Interviewer: You say you’re not a thinker -

Borges: No, what I mean to say is that I have no personal system of philosophy. I never attempt to do that. I am merely a man of letters. In the same way, for example that – well, of course, I shouldn’t perhaps choose this as an example – in the same way that Dante used theology for the purpose of poetry, or Milton used theology for the purposes of his poetry, why shouldn’t I use philosophy, especially idealistic philosophy – philosophy to which I was attracted – for the purposes of writing a tale, of writing a story? I suppose that is allowable, no?

Borges is so good, and so obviously profound, that it would be easy for him to be grandiose. But his humility – which I think comes from both his sincere appreciation for the many thinkers who came before him and his astonishment at the mysteries of life and the universe – always shines through. The interviewers, who are philosophers comfortable with their status as great arbiters of profundity, try to draw him into their world, and if he doesn’t quite bite, he does at least nibble at the bait…

Interviewer: You share one thing certainly with philosophers, and that is a fascination with perplexity, with paradox.

Borges: Oh yes, of course – well I suppose philosophy springs from our perplexity. If you’ve read what I may be allowed to call “my works” – if you’ve read my sketches, whatever they are – you’d find that there is a very obvious symbol of perplexity to be found all the time, and that is the maze. I find that a very obvious symbol of perplexity. A maze and amazement go together, no? A symbol of amazement would be the maze.

But he’s quick to add something else, which so good it makes me want to pick up the pen:

But I would like to make it clear that if any ideas are to be found in what I write, those ideas came after the writing. I mean, I began by the writing, I began by the story, I began with the dream, if you want to call it that. And then afterwards, perhaps, some idea came of it. But I didn’t begin, as I say, by the moral and then writing a fable to prove it.

Another dreamer (in a very different context) would, I think, approve…

April 16, 2014

Who’s Cheating America: A Matter of Integrity

Artistic reenactment:

Attorney: Hi there. I’m Chris Linton from Birmingham, Alabama. I’m an attorney, but don’t hold that against me.

Investor: Hello. What can I do you for?

Attorney: Hahahahaha, good one. [Gets serious.] Look, I’ve got a great new business going and the sky’s the limit. How would you like to get in on the ground floor?

Investor: I don’t know…you look a little young…

Attorney: I’m thirty-four years old!

Investor: That’s all?

Attorney: That’s enough! Look, here’s what I’m going to do. I’m setting up what’s called a factoring business. Lawyers who work for the state will submit vouchers to me so they can get paid quickly. I then get the money from the state for the work they performed.

Investor: How do you make money on that?

Attorney: I receive a cut of the money.

Investor: How much money?

Attorney: Enough to pay for my home, construction projects at the residence, private jet flights, vacations, recreational vehicles, furniture, luxury items, Auburn University football tickets and a donation to the Heisman Trophy Trust. All without committing wire fraud, mail fraud, money laundering, securities fraud, or bank fraud. it’s win-win-win-win-win-win-win.

Investor: That sounds like a lot…are you sure that’s all from your business?

Attorney: Mostly from my business.

Investor: Mostly?

Attorney: Some might be from investments in my business. I occasionally dip into the fund. Here and there. Make ends meet. Keep the lights on. You know how it is.

Investor: Investments? You mean from people like me?

Attorney: Sure. But you don’t need to worry. My business is called Integrity Capital.

Investor: Oh! Why didn’t you say that in the first place? [reaches for wallet]

Attorney: Has a nice ring to it, doesn’t it?

Investor: [writing check] It sure does.

Cut to: exposure, scandal, arrest, guilty plea, and a former attorney now facing up to 65 years in prison. Argh! Live up to your name, Integrity Capital! Stop cheating America!

Oh the irony… first “London Associates” and now this…the irony, the irony…

Previous entries in our Who’s Cheating America? series:

Breakfast at Tiffany’s

The Bad Penny

Zip-A-Dee-Doo…D’Oh!

Lovers of Literature

Let’s Go Fly a Kite!

Sharing Time (or Doing It?)

The Lonesome Highway

The Overzealous Recyclers

The Opera Lover

Unclean Hands

The Smoke-Filled Room

Gung Ho!

The Billionaire vs. the People

The Highly Profitable Non-Profit

The Murky Coin Collector

April 15, 2014

Small Press Shout-Out: Luath Press!

Our globetrotting search for good people putting out good books continues! Last week we journeyed to Australia for a visit to the kindhearted and energetic Pantera Press. Up this week: the land of mountains high-cover’d with snow, straths and green vallies, forests and wild-hanging woods, torrents and loud-pouring floods…that’s right! We’re going to visit the Land of Rabbie Burns…

Scotland!

And this time I’m not so fearful of blundering into stereotypes, since Luath Press has taken its name from the old Ploughman Poet himself. But what’s a Luath? As their website explains:

Luath Press takes its name from Robert Burns, whose little collie Luath (Gael., swift or nimble) tripped up Jean Armour at a wedding and gave him the chance to speak to the woman who was to be his wife and the abiding love of his life.

Abiding love of his life! What a great story!

Their connection to Burns runs deeper than taking the name of the wee little collie:

Luath Press was established in 1981 in the heart of Burns country, and is now based a few steps up the road from Burns’ first lodgings on Edinburgh’s Royal Mile. Luath offers you distinctive writing with a hint of unexpected pleasures.

We’ll check out that distinctive writing in a minute, but first, take a look at the view from their offices:

Stunning. It would be hard not to be inspired by a view like that.

Edinburgh’s literary history needs little detailing, but let me just say that I myself have spent several good nights in Edinburgh, soaking up the charged intellectual atmosphere, and many, many other nights enjoying the works of Scottish authors from Robert Louis Stevenson and Robert Burns and Sir Walter Scott and John Buchan all the way through to Muriel Spark, Ian Rankin, J.K. Rowling, and Kate Atkinson (with plenty of room in my heart (and mind) for David Hume and Adam Smith). And as for the Greatest Biographer of All Time…well, let’s just say I nearly named my first-born son Boswell.

So back to Luath Press, with their gorgeous view of their gorgeous city. They’re a classic gap-filler small press, bringing out books that readers are looking for but other presses have missed. Their catalog sports an eclectic mix of subjects, from walking guides to poetry to crime thrillers. A huge Scottish flavor. Like Rabbie Burns. And the Old Course. And the little daughter of the owner of the Western Isles guesthouse, who asked me as I was checking in, “Have you got a weeboy?” I smiled and shook my head, with no idea what a weeboy was. Some kind of video game? Her mother explained that the last guests who stayed there had had a small (wee) boy, who had been a good playmate. “No,” I had to tell the disappointed little one. “I haven’t got a wee boy.”

Scotland!

Given my own literary tastes, I’d start with the Crime and Literary Fiction sections of their catalog. But if I were headed to Scotland soon (and how I wish I were!) I’d be loading up on their Scottish history, their Scottish storytelling, and their extensive Scottish travel sections.

Then I’d cap it all off with a little of my old friend Balvenie (the Doublewood, naturally):

And of course, a special onward and upward (no, not bagpipes):

(Okay, they’re from Glasgow, but let’s not be splitting a bristl’d hair!)

You can check out my own adventures in small pressing…eh, we’ve done that one enough. Amazon author page is here. Or how about reading about the Friday Night Failures of a woeful Wisconsin football coach desperate to stay relevant? Or the latest excerpt from the insane asylum known as the Greater Washington D.C. area? Or the genius who bet his car on the Rose Bowl in one of our recent Terrible Poems? Or just check out Little Pickle or Bobbledy Books or Pantera Press and get your smile on.

Who am I missing? What other small presses deserve some attention? Let me know in the comments or shoot me an email at jackewilsonauthor@gmail.com.

Previous Small Press Shout-Outs:

Pantera Press

Bobbledy Books

The New Press

Les Figues Press

Little Pickle Press

Black Balloon Publishing

Akashic Books

Ugly Duckling Presse

OR Books

SALT Publishing

The Permanent Press

Kaya Press

Tiny TOE Press

Atticus Books

Soho Press

Graywolf Press

Overlook Press

Other Press

April 14, 2014

Awaking to Find You’re a Monstrous Vermin (The Promotion Excerpt #6)

In Which the Narrator Tiptoes into the World of the Mysterious Mina Meinl

Even now it gives me chills to think of that moment when I heard the name for the first time. The way the words sounded, coming through those teeth. It was a name at the heart of the strangest experience of my life. And yet it sounded so foreign to me—I, who was then so innocent—that I initially thought it was the name of a corporate entity. Mina-Meinl. A company that made industrial machinery, perhaps. An investment vehicle that shipped grain out of the Ukraine. Not a person. Not a woman. Not someone I would ever, ever meet.

“What’s that?” I asked.

“Not a what but a who,” Linn explained. “An investor of some kind.”

She explained what was known. During the exam, the accountants had discovered that this woman, Mina Meinl, had been offered co-invest opportunities on all the investments for all of the funds.

I was familiar with the concept of co-invest. Fortinbras Capital Management spent a ton of money looking for good investments—a hotel chain in Abu Dhabi, say, or an office park in Kuala Lumpur, or a string of mines in South Africa. After the Fortinbras funds had invested as much as they wanted, Fortinbras would open up investment to other investors as well.

Sometimes these opportunities were used as favors—a sweetener to get a prospective investor into one of the large funds. All this was fully disclosed, of course, and consistent with their fiduciary obligations. Nevertheless the SEC examined co-invest carefully. The first thing the SEC staff looked for was people who had gotten more than their fair share. According to Linn, the odd thing about Mina Meinl was not how much she got but how little.

“Five million in co-invest blends in,” she said. “Fifty thousand stands out.”

“Who is she?”

“Nobody knows.”

“How did this happen?”

Linn shrugged.

My internal investigation antennae were twitching. I specialized in this! I casually said that it sounded like they could use my services.

“Maybe I should call Darrin?” I suggested, referring to the general counsel of Fortinbras.

Linn shook her head. “No need. They decided it’s not material. The SEC didn’t notice it, and the next exam won’t be for a couple of years.”

“Aren’t they trying to figure it out?”

Linn said she didn’t know. She suspected that Darrin had other problems to deal with.

“Mina Meinl,” I said. Saying the name out loud gave me goosebumps.

“The great mystery,” Linn said.

We had to talk about recruiting. I made a few general remarks about process and goals, and she nodded as she checked the messages on her phone, but in fact my mind was just as preoccupied as hers.

A lot had changed. I had a new set of responsibilities, giving me a sense of purpose. We would be hiring a lot of new people, which was a large commitment of resources. And for the people we’d be hiring, it would be life-changing. It was important to make sure the new hires fit in our culture and wanted to do what we had in mind for them. The entire firm depended on its people, and I would be a major contributing factor to the future of the firm.

Looking back, I can see that something else was already growing in me. A seed had been planted and had already taken root. Soon it would sprawl across my mind like fast-growing kudzu, dominating all other foliage with its tangled, smothering vines.

Mina Meinl. The great mystery indeed.

Next: In Which the Narrator Begins to Realize His Deputy Could Destroy His Life-Changing Plans

Need to catch up? Check out Excerpt #5: In Which the Narrator Hears the Name That Will Forever Alter His Future. Or start at the beginning.

Can’t wait to read the whole thing? A full version of The Promotion is available on Amazon.com in paperback and Kindle versions.

April 11, 2014

Formatting a CreateSpace Book in 2014: One Quick Tip

I’ve gotten some good feedback from the post touting the still-timely advice of Guido Henkel and his e-book formatting guide. But what about formatting for print-on-demand? That’s no less confusing – and I never found a Guido Henkel to serve as my Virgil.

So it’s Googling, and more Googling, and a lot of trial and error. Eventually I came up with something I was very happy with and a second try that turned out even better, so I thought I’d mention at least one CreateSpace trick that worked for me.

Like many readers, I was frustrated by the faintness of the text in my initial attempt. Comparing it with the paperbacks on my shelf, I would say the print readability was somewhere in the third quartile of printed books (is that the right way to say worse than half but still better than about a quarter?). But was it a problem with the font? The pdf creation? Or was it merely a CreateSpace issue I would have no control over? Online research took me in circles and got me nowhere.

I’m happy to say it’s fixed in The Promotion, and I’m so pleased I have a retro project in store for The Race.

For the font of The Race, I went with the default font employed in the CreateSpace template, which was Garamond 11. As I said, I thought it looked pretty good, but I thought it could be improved. On some Internet advice I tried Palatino Linotype, which is a bigger font, so I reduced to 10 point. And then – and this is really the key – I switched the line height setting from 1.0 to 1.2. I gather this is an obvious move for an experienced typographer, but I was not experienced. (I don’t know why the CreateSpace template didn’t help me out a little more here. Seems like an obvious move.)

In any case, the difference (based on my sample size of five books of each) is striking. The Promotion‘s text looks darker and more professional, and (most importantly) is much more legible. I’ve seen some who complain about adding to page length (and therefore cost of printing), so maybe that’s why the template is what it is. But for me, because these are novellas, the added length is actually a plus. I’m getting close to the out-of-danger zone of 130 pages, which will let me put text on the spine without fear of the dreaded “slippage” running the text onto the front or back cover.

In any case, I thought I’d share my results, which I’ll update if subsequent printings prove me wrong. And since with print-on-demand, every book has the chance to be a little bit different, I’ll need to count on reader feedback to let me know if the print becomes feeble. Let’s channel our inner Mario Soldati and try to view that as a feature and not a bug, and keep things moving onward. (And upward. Cannot forget that part!)

A History of Jacke in 100 Objects: #1 – The Padlock

I have a theory that everyone has what I call the Personal Singularity. This is the period in your life when some trend or phenomenon so defines you, so matches where you are in life, so inspires you to be all that you can be in a particular direction (for better or worse), that you will never be that in sync with anything else in your sorry little life, ever again.

For a long time I thought my own moment of Personal Singularity had come when I was in high school and David Letterman’s show was on NBC (I want to be Dave! I can be Dave! I AM DAVE!). Now that I’m a warped and frustrated old man I realize it was actually the years I spent with this guy:

The odd thing about the Personal Singularity is that it’s rarely disputed. People around you—all your loved ones—can agree on what it is, and you yourself probably won’t argue.

Saturday Night Fever? Yep (embarrassed laugh) I was REALLY into that. Young Tiger Woods tearing up Augusta? Hey, my golf clubs are still in the trunk of my car.

For my friend’s father, it was Sanford & Son. Nothing has made him laugh harder than Redd Foxx and his son Lamont in the junkyard. He still does the “I’m coming to join you, Elizabeth” routine.

Yes, yes: life was good for Monte Strunz when he had Sanford & Son to look forward to each week.

For our high school football coach, the Moment of Personal Singularity was the 1985 Chicago Bears.

Jim McMahon, Mike Singletary, Willie Galt, the Superbowl Shuffle, the Fridge(!), and Sweetness (the one Bear who was so awesome that even we Packers fans could not help but admire him). And of course, Coach Ditka. Coach Olin didn’t just admire Mike Ditka. He wanted to be Ditka. He was Ditka. He was powerfully built, just like Iron Mike, and he had the same coloring and the scowl. He had brushed his hair back and sported a moustache several years before Ditka arrived on the scene, as if he had sensed that Ditka was going to come along and look like that. The universe rarely exhibits that kind of cosmic harmony, but when it does, it is awesome.

It hardly mattered that our team was terrible and had been for five years. His career record was something like two-and-fifty. Not too good! And yet he was out there every fall, enduring heat and mosquitoes in August and rain and wind and cold in November, pacing the muddy turf like a stallion with a clipboard, chomping gum, barking out commands. Leading his men, like a hero—like his hero, in fact, the much more successful avatar who had won a Super Bowl just a few years before. Back then there was something dignified in resembling Coach Ditka, even when your team was losing a game 55-0. My senior year we lost by that score—by that exact score—two weeks in a row.

Once at halftime we came into the locker room down 20-0. Coach Ditka (we all called him that) gave the best speech of his life, a true barnburner. I felt like weeping, knowing we were not worthy of such a speech.

“Men,” he said at the end. “You have two choices. You can go out there and play another half like that and you can lose 40-0. Or you can go out, play like men, and WIN! THIS! GAME!”

We stomped and shouted and pounded each other’s shoulder pads…and went out and lost by the score of 40-0. It was incredible. I mean, what were the odds? We were cursed like that.

After the game, Coach Ditka came in to address us again. This time there was no speech. This time he could only shake his head.

“See you Monday, boys,” he said.

Yet somehow in spite of all that he managed to maintain his dignity. I always thought that about ninety percent of that was because he looked just like Ditka.

His assistant coaches, on the other hand, had little dignity to spare. I’m not sure how much was due to substance abuse. Maybe that was the cause. Maybe a symptom. Either way it dragged them down.

Coach Spangler had a constant sniff from an “air conditioner cold” that we thought was a euphemism for cocaine. For all I know he was snorting steroids. It wouldn’t have surprised me. It would at least explain his psychotic intensity, which reached its peak during pre-game warmups when he ran around like a crazed animal, grabbing facemasks and head-butting players. It did not seem to bother Coach Spangler that the player was wearing a helmet and he very much wasn’t, or that the collision between his face and the player’s facemask bent his glasses sideways and shredded his skin and sent blood streaming down from the bridge of his nose. (“War wounds,” he would growl, as he batted his face against another player’s uniform to sop up the blood.)

We called him “Sparky” because what else do you call a guy like that?

Another assistant had a different demon, a more conventional one for an ex-athlete in Wisconsin: beer. Or as he put it, “cold ones.” Coach Cold Ones (a nickname we called him to his face) had “seen some shit” in his life. He had been divorced five years earlier and the rumor was he had not dated since then. He lived in a trailer. Once in a while he talked about his son, a “deadbeat” who lived in Florida. Doing the math it seemed that Cold Ones had gotten his ex-wife pregnant when she was a fifteen-year-old sophomore and he was a senior about to leave for Vietnam. College had never been in the cards for Cold Ones.

Maybe it was the war, or the ex-wife, or the son, or us—something chased him into alcoholism. He started out competent, more or less. A few weeks in—around the time we were 0-3 or 0-4—he began coming to practice in a giddy mood. He made up new plays for us and laughed at our attempts to run them. (Once he had us run a reverse, then a double reverse, then a triple, a quadruple, and finally a quintuple reverse, which we executed with all the grace of a wrecking ball tearing into a building. By the end of the play he had fallen on the ground, giggling and admitting that he “had a few cold ones” on his way to practice.)

By mid-October the giggling days were over. Now he showed up in a dark, foul mood, stumbling over words and screaming at anyone who so much as smiled.

“You think it’s all a joke. Why are you milesing? Sah-mile-ing. You think it’s a co-in-di-cence that you’re losing allatime? You’re out there gabassing… grassabbing… bassgrabbing… goddammit stop laughing football is SERIAL.”

But it wasn’t serious, not for us—there was just no way to deny that our team was a joke. Someone pointed out that every single road game we played that year was the other school’s homecoming game. That’s what we represented, what we were best at: a guaranteed win for another team. We got used to waiting through long halftimes as bands played and convertibles bearing royalty pulled onto the field, the victory already secured. By the second or third time this happened, it stopped bothering us. We had our dignity to maintain too. So we stopped warming up, stood in a line, and traitorously waved at the King and Queen of our enemies. Our coach didn’t like it, but that’s what we did. We laughed at ourselves. I didn’t feel great about it—it didn’t feel like the right way to deal with failure, as if we were dooming ourselves to a long lifetime of not caring. I sort of knew that it would be better to be serial. But I joined in anyway.

That was our team, and those were our leaders. Ditka, Sparky, and Cold Ones. It’s amazing we finished the season.

And for a moment it looked like we might not.

#

No one seemed to know just who had put the gleaming new padlock on the equipment shed. All we knew was that none of us could open it. And that everyone who knew the combination had gone home. And that all of our equipment—the cones, the tires, the tackling dummies, the footballs—were inside.

The team gathered around the battered old structure as Coach Ditka stood in his group of three, shrewdly assessing the situation.

“It’s locked,” Sparky said, talking faster than anyone else on the field could think. “We don’t know the combination. Who put this here? Who put this here? Everything’s inside. Everything, everything, everything. The pads are in there the footballs the dummies everything we need is in there where’s the combination who put this here how’re we gonna open it how’re we gonna practice?”

It was cold and had been raining for days. We started to make our plans —if practice were cancelled, we could head to the Pizza Hut, maybe make it to a movie…

“We’re NOT canceling practice!” Cold Ones roared. “We can run sprints! We can do pushups! We don’t need no e-pick-quent for anyathat!”

A couple of guys shrugged and started walking off the field, toward the edge of the hill that sloped down to the locker room.

Cold Ones took offense. “You leave now and you’re QUITTING THE TEAM!” he hollered at them.

“That’s the point,” one of them hollered back.

“Don’t come back then!” Cold Ones said.

Ordinarily that is not something you need to say to someone who has just quit. But sometimes Cold Ones’ responses were a little delayed.

Coach Ditka stood staring at the padlock, chewing his gum slowly. The shed was so old and decrepit—you could practically see the white paint flaking off in the drizzle. We probably could have just torn the thing down, if he’d asked. Maybe he was afraid we wouldn’t be able to do it. Maybe he was afraid we would lose to a shed.

“Have to cut it,” he said at last.

Cut it! We looked at one another. That would be cool. Not something you saw every day. And better than running, or doing pushups, or whatever physical torture Cold Ones and Sparky would come up with.

“Need a tool,” Coach Ditka announced, as if he were the captain of an endangered vessel initiating some highly technical maneuver. Think of Captain Aubrey, preparing to take down the Acheron:

Until the signal calls, you’re to spill the wind from our sails, this will bring us almost to a complete stop. Gun crews, you must run out and tie down in double quick time. With the rear wheels removed, you’ve gained elevation. and without recoil, there’ll be no chance for re-load, so gun captains, that gives you one shot from the lardboard battery… one shot only. You’ll fire for her mainmast.

“Need a tool,” our captain said again. “A cutter of some kind.”

And Sparky the first mate sprinted across the hill, down to the maintenance room. We all made sniffing noises, our sophomoric cocaine joke whenever he disappeared from view. We were still laughing about this when he returned, lugging a tool for the captain, a giant bolt cutter with rubber handles and a disproportionately tiny head. It was three and a half feet long, heavy and not easy to carry.

Coach Ditka chewed his gum at least a dozen times before he said anything. Maybe he was reflecting on his lot in life. Maybe he was thinking, behind his Burt Reynolds moustache and under his Chicago Bears baseball cap, that he could not quite believe that he was here, that his fate was to coach nineteen—well, now it was seventeen—players with no ability or hope. Maybe it suddenly struck him that his loyal deputies were completely insane.

Or maybe it was not an epiphany. Maybe this was something he had thought many times, and this was only the latest instance. Like a recurring chest pain you know is probably trouble, but which you’re powerless to do anything about.

“Cut it off,” Coach Ditka finally said.

Sparky leaped forward, swinging the heavy tool, which took on its own momentum, like a mace with a ball and chain at one end. Holding it waist high, he waggled the notch of the bolt cutter into place against the padlock’s hook. He squeezed.

The handles did not move.

Sparky grunted. He clenched again. Nothing. He took a breath, set his shoulders, and clenched a third time. Nothing.

“Ayah-yah-yah-yah-yah-yah-yah,” he shouted, grunting and squeezing. He squatted down and looked kind of like Angus Young strutting across the stage with his guitar sticking out.

The padlock stayed where it was. Implacable. Unyielding. We were losing to a padlock. Well, why not? We lost to everything else. The joke running around the conference was that we held an intrasquad scrimmage and finished the day 0-2.

“Give me that!” Cold Ones shouted. He was a much larger man, probably twice Sparky’s weight, and he moved in to take away the tool. Sparky was embarrassed and refused to surrender it.

“Give it me!” Cold Ones shouted. “GIVE IT.”

He managed to wrest one of the handles away. Sparky was hopping on one foot, refusing to let go of the other. He looked at Coach Ditka for help. One more try, Coach, his eyes said. I can do it.

Coach Ditka refused to acknowledge him. Captains must do what’s best for the ship. Sparky hopped to the side, defeated.

Cold Ones lifted the tool with ease. He set it up with nonchalance and flexed his biceps.

Nothing happened.

He squeezed again, harder this time.

Nothing.

Two more kids walked off the field. Nobody said anything to them. Down to fifteen.

I couldn’t leave—I couldn’t take my eyes off our mountainous, half-drunk, angry coach, unable to complete what seemed like a ridiculously simple task. How could this little piece of metal stand up to this enormous tool and this man—this Paul Bunyan of a man, all two hundred and seventy-five pounds of him, whose whole life was football and wrestling and bar fights and loading trucks and lowering engine blocks into muscle cars and crushing beer cans against his forehead and clenching his eyes against the dark memories of combat—how could such a man be defeated by such a simple thing?

He put the bolt cutter between his knees and spit on his hands. Another kid left.

It was raining harder. “Might need to cancel,” Coach Ditka said. “Come back tomorrow.”

That was the cue for half a dozen more people to flee. Sparky chased after them, shouting something about doing pushups in the hallway.

Cold Ones lifted the tool.

I looked around. It was raining hard now. Everyone else was gone, headed back to the locker room. It was only me, and Coach Ditka, and a desperate man engaged in the struggle of his life.

“Let’s go, Cold Ones,” Coach Ditka said. “Get it done.”

“Yaaaaaaaaaarghhhhh,” the coach cried, pouring everything that remained of his futile life into squeezing those handles. His arms shook. His shoulders quaked. Tendons popped out of his neck. His face turned bright red, then purple.

I waited for Coach Ditka to say something else—more encouragement, or to tell him to stop. No, John Henry! Don’t race the steam engine! You’ll die! But I didn’t want him to call it off. I wanted Cold Ones to succeed—or rather I was afraid of what might happen if he didn’t. In general he didn’t seem to have much to live for. If it had been a mental task—let’s say he didn’t know what seven times eight was—he’d have laughed it off. But what effect would failing at such a simple physical task have on him? Humiliation? More drinking? Serious depression?

Suddenly I thought that if he couldn’t get that stupid padlock off we might never see him again. He’d stop coming to practice and years later we’d hear that he lived in a tent by the river.

Coach Ditka may have been thinking the same thing. “Let’s go, Cold Ones,” he growled. “It’s Go Time, Big Man.”

Cold Ones had a wild look in his eyes. The tool was cinched against the lock now, gripping it like Beowulf’s hand clamping down on Grendel’s arm before ripping it out of its socket. The handles started to rise. Cold Ones was on his tiptoes, exerting maximum strength.

“Come on, Cold Ones,” Ditka said, his voice rising with excitement. “You got this!”

In a burst of inspiration, Cold Ones changed his grip on the tool, lifting it higher, as if he were a weightlifter jerking the weight above his head. His hands were now on either side of his ear, allowing him to bring the full force of his biceps—his favorite muscles, his pistons, his engines, the ones he used to kiss and say “this one’s called Pride and this one’s called Joy”—to bear on his foe.

It thundered. I wondered if lightning might strike this metal tool and this giant working man. It would be an incredible end. I was not sure it was something I should see. If that happened, maybe I should turn away, like Indy at the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark.

Cold Ones gave a final, life-affirming squeeze.

The padlock broke. I’m convinced that the breaking of the padlock was his moment of Personal Singularity, when he proved, on a rain-drenched field, in front of a man he admired, that he could do what he was put on this earth to do.

Yes, it was his moment. And it did not even last a second.

The padlock finally broke. But the snap of metal was instantly followed by a dull, hollow thud. With no resistance, the two handles suddenly flew together, hammering the two sides of Cold Ones’ head. The tool fell to the side. Cold Ones staggered to the ground. Not in any kind of quick, dignified fall. No, it was much worse than that. His body crumpled down, and he fell in stages, like a tranquilized elephant.

When the bolt had snapped, Coach Ditka had raised a fist in the air, pumping it in triumph before realizing what had happened. Now he was so shocked he didn’t know what to do. His arm stayed where it was, suspended in mid-air. His fist unclenched. The arm didn’t move.

Cold Ones lay on his side. He was not moving either.

Coach Ditka and I looked at each other. I thought there was fear in his eyes. There must have been in mine as well. The spooky sound of metal against skull still rang in my ears. It had sounded like a baseball bat being dropped on concrete in an empty tunnel.

Cold Ones’ eyes were closed.

Coach Ditka’s smirk came back. “Come on, Cold Ones. Get up.”

“Don’t be dead,” I said, my voice ghostly. “Please, Cold Ones. Please don’t be dead.”

He shuddered.

Coach Ditka shook his head. “He’s not dead. Get up, Cold Ones. Stop loafing.”

Tough love was effective with Cold Ones. His eyes fluttered open. He blinked several times, eyes rolling. He did not appear to know where he was. Then he rolled over, lifted his body to one knee like a truck being hoisted by a jack, and squeezed his head with both hands.

Coach Ditka and I tried to help him stand. He wriggled away from both of us and walked back to the school of his own accord. Slowly, very slowly, but of his own accord.

I thought I could see the anger and shame in every step. Life had dealt Cold Ones yet another blow. How many more of these could one man take and remain intact? How much dignity can you lose before you’re no longer a man?

#

As we were stretching the next day—down to 11, the magic number below which our remaining games would be lost by forfeit (not that it would matter to our record)—the athletic director arrived with a new padlock. Cold Ones got there early, scowling as they were installing the new padlock. The athletic director distributed the combination to all the coaches, but this wasn’t enough for Cold Ones. As soon as the AD left, he went into the maintenance room and returned with a can of spray paint. Then he walked slowly to the the equipment shed and sprayed the combination on the side in giant blue numbers. Later we would find that it was also spray-painted on the side of the school by the junior high gym, on the floor of the men’s locker room, and on the athletic director’s truck, which had been parked in the faculty parking lot.

For the rest of the season we were mocked as the school so stupid we painted the combination to the padlock on the side of our equipment shed. Players from other schools robbed us blind, interfering with our ability to practice as if they needed a competitive advantage. Every day brought fresh misery: we would open the door to the shed only to find it cobwebbed with toilet paper, for example. On our last day of practice we were greeted by the top half of our mascot’s costume—an oversized Viking head—dangling from a noose.

It was a tough season filled with failure. We had been the laughing stock of our conference. But now, after the padlock incident, even our own school turned on us. Even our parents were ashamed. I could understand why some of them demanded that Cold Ones be fired, and why some players—embattled as they were, embarrassed as they were—piled on. Cold Ones had problems. Cold Ones was a joke. Cold Ones had to go.

And maybe they had earned that. Maybe they had their own dignity to preserve. The guys who hadn’t quit, who toughed it out—they all had lives to live, futures to look forward to. Why did they deserve to be stigmatized? Maybe it’s better to blame the coach than accept your own failure—not as a general rule, but maybe in this case it was warranted. Maybe having someone to blame was a positive thing. Maybe, in the face of so much failure, it was necessary.

So yes, I could understand why the guys mocked Cold Ones, whose real name was Gary. I could see why they told everyone about his ridiculous plays and his drunken comments and the time he smashed his own head with the bolt cutter (which none of them had witnessed). I knew why spray-painting a padlock’s combination onto a shed became our community’s shorthand way of calling a grown man such a hopeless moron he should never be anywhere near a high school. Because what kind of example could he possibly set? What could a guy like that have within him to help kids like us learn anything?

I understood why everyone laughed at Cold Ones. I just never did.

#

Enjoy this post? Are you that sadistic? Or in need of catharsis? In any case, you can read more about Wisconsinites taking a shot at redemption in The Race, in which a scandal-plagued governor tries to overcome an even greater obstacle than the one faced by Cold Ones. Or you can read about a lawyer gone mad in The Promotion. All books available in print and electronic format. Enjoy, my fellow miserables!

April 10, 2014

Who’s Cheating America: Breakfast at Tiffany’s

Image Credit: guardian.co.uk

No, no, this isn’t about the divine Audrey Hepburn. We didn’t catch her cheating, thank god. It’s just a boring old insurance company dispute with Tiffany’s, the world-famous jeweler’s. So boring, in fact, I had to jazz it up with a photo. Here’s another:

Image Credit: Elegant Audrey

Sigh. Now onto the case, which is captioned Those Interested Underwriters at Lloyd’s, London who subscribed to the policy of insurance numbered BO80111433 v. Lederhaas-Okun et al.

Huh?

I thought this was about Tiffany’s? You mean there’s more…?

Lloyd’s of London underwriters brought a suit in New York state court Wednesday against a former Tiffany & Co. executive about to enter prison on charges of stealing merchandise from the luxury retailer and the jewelry trader that allegedly fenced her loot, seeking to recover the resulting $5.4 million loss.

Fenced her loot? From Tiffany’s? And she was a Vice President of Product Development?

Oh boy.

In her plea, Lederhaas-Okun admitted that she took routinely checked out pieces of jewelry from her employer and took them home to Connecticut before selling them to a leading international buyer and seller with an office in midtown Manhattan.

Hmm. She checked them out, saying they were damaged and needed to be written off for insurance anyway. Then she took them home and sold them. How in the world did she ever get caught?

Although prosecutors never named the alleged fence in open court, Lloyd’s asserts that checks from the jeweler show payments for the stolen goods totaling roughly $1.3 million in connection with at least 31 different transactions.

Checks??? The fence paid her by check??? I thought that’s what bitcoins were for! (Just kidding, authorities with subpoena power!)

The good thing about executives getting caught is that they’re not stupid enough to lie.

After she was fired in February, Lederhaas-Okun allegedly stated that she only recently checked out the missing jewelry to create a PowerPoint presentation for her supervisor, a draft of which could be found on her office computer.

In actuality, the missing jewelry had been checked out months earlier and her supervisor knew nothing of any planned presentation, while a search of her office computer revealed no draft, according to prosecutors.

One little fib!

At another point, Lederhaas-Okun claimed the missing jewelry was in a white envelope in her office, but a search following her departure from the company turned up nothing, prosecutors said.

Okay, two!

This second one is really hand-in-the-cookie-jar thinking. “Um, the jewels? Which jewels? Oh, those jewels…um…they’re in my office…in a white envelope…go look!” [Gulp.]

So there we go. From Breakfast at Tiffany’s to Breakfast at a Correctional Facility in West Virginia. Moon River to Up the River. And to an ignominious spot on our list of Who’s Cheating America.

Previous entries in our Who’s Cheating America? series:

The Bad Penny

Zip-A-Dee-Doo…D’Oh!

Lovers of Literature

Let’s Go Fly a Kite!

Sharing Time (or Doing It?)

The Lonesome Highway

The Overzealous Recyclers

The Opera Lover

Unclean Hands

The Smoke-Filled Room

Gung Ho!

The Billionaire vs. the People

The Highly Profitable Non-Profit

The Murky Coin Collector

April 9, 2014

Self-Publishing Update: Reading on a Smartphone

Ugh, is there anything worse for today’s author than to think about someone reading their book on a smartphone? We like the image of a reader luxuriating with a stately hardcover, a sleek paperback, or—in a pinch—an e-reader. But a tiny-screen phone? Is no tradition sacred? Why not throw words out too, while we’re at it?

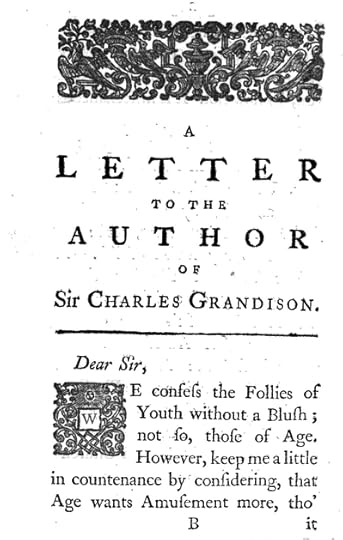

Ah, reader. You probably know me well enough by now to know I am a positive thinker. (When I’m not cowering in fear of my Dark Lord.) So I direct your attention to Clive Thompson, who points out that 18th-century books looked like smartphone screens:

Image Credit: Google Books via Clive Thompson

Thompson explains:

That small-page format was quite common back in the 18th century. It’s known as octavo with pages that are about 6 inches by 9 inches. The entire Conjectures is only about 8,000 words long, but it was common to print essays in this pretty little style, because it had great ergonomics: It made for easy one-handed reading and portability.

Thompson has much more on his blog, including a brief history of printmaking (explaining the size) and photos comparing it with today’s smartphone screens. He even offers this personal benefit of the format:

In fact, one of the oddly useful things about reading War and Peace on your phone is that the octavo-like format makes the epic enormity of the tome less intimidating: It’s just one little page after another, each one oddly inviting. I tend to blow up the font on my phone to quite large, so each page has only a few hundred words on it, precisely the way that [an 18th-century book] is laid out…

Fascinating. And of course, I would be remiss if I didn’t point out that my books The Promotion and The Race are available in a variety of formats, and from a variety of booksellers. Happy reading!

April 8, 2014

Small Press Shout-Out: Pantera Press!

We’re headed down under for this week’s small press shout-out. And what a trip it is! Even the most seasoned, curmudgeonly book buyer will find it hard to return from the Pantera Press website without wearing a smile. This press exudes friendliness and charm, from their mission-like statement “our passion is publishing books readers rave about by discovering & nurturing talented new authors, & fostering debate,” to their trademarked slogan “good books doing good things,” to their “strong ‘profits for philanthropy’ foundation.”

This is a press that’s unashamed to say, “We’re thrilled about what we’re doing. We hope you get excited too!”

I’m getting there, Pantera!

Actually, their entire statement is worth quoting:

Some great businesses have started in home garages. Think Disney, Amazon and Google. Pantera Press sprang to life around the story-loving Green family’s kitchen table because their garage was full.

We view the so-called ‘slush pile’ of Australian unsolicited manuscripts differently. To us, it’s a valuable resource, an underexplored diamond mine. When we started, we felt that if everyone’s supposed ‘to have a book in them’, Australia must be bursting with 22 million stories, many of them gems waiting to be discovered, polished and set for readers to enjoy! As well as publishing great stories, we aim to contribute to the wider community, hence our unique ‘good books doing good things’ approach.

Awesome! How is it working out?

Pantera Press has grown so fast since our start that we’ve had to quit the kitchen table for a real office, but at least our board table sports a ping pong net. Having released our first titles in 2010 (in print and in e-books), we were short-listed in 2013 for the Australian Book Industry’s Small Publisher of the Year Award. We’ve been developing a stable of talented new authors writing gripping tales getting rave reviews, and assembled a team of seasoned industry professionals from some of the biggest names in publishing, such as editors and designers and our distribution partners at Simon & Schuster.

I’m in! And what kinds of books are they delivering?

Good ones! Of course!

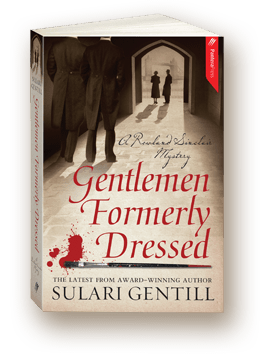

Well, okay, to be more specific, it’s mostly historical crime fiction (think bowler hats and bludgeons, church ladies and candlesticks) and page-turning thrillers on the fiction side:

And engaging political topics on the non-fiction side. Their WHY vs. WHY series offers both sides of a debate (nuclear power, gay marriage, etc.), combined into one book:

Onward and Upward, Pantera Press!

I tried so hard not to make terrible Australia jokes in this post. I hope the tribute to Luc Longley at the end didn’t ruin my post. He’s one of my favorite players, on my all-time favorite team! No irony or backhanded compliments intended! You can read about my own adventures in publishing, including my tips on e-book formatting for 2014, or you can travel to my new author page at Amazon.com to see the latest results.

Who am I missing? What other small presses deserve some attention? Let me know in the comments or shoot me an email at jackewilsonauthor@gmail.com.

Previous Small Press Shout-Outs:

Bobbledy Books

The New Press

Les Figues Press

Little Pickle Press

Black Balloon Publishing

Akashic Books

Ugly Duckling Presse

OR Books

SALT Publishing

The Permanent Press

Kaya Press

Tiny TOE Press

Atticus Books

Soho Press

Graywolf Press

Overlook Press

Other Press