Marc Goergen's Blog, page 6

October 11, 2014

How Larry Page and Sergey Brin manage to control 56% of the votes in Google Inc. with a 14% ownership stake.

Before we can proceed just a reminder what we mean by control and ownership. Ownership is defined as ownership of cash flow rights. Cash flow rights give their holder a pro rata claim to the firm's earnings and a pro rata claim to the firm's assets if the firm is to be liquidated. Control is defined as ownership of voting rights. Voting rights give their holder the right to vote for or against a number of agenda points at the annual general shareholders' meeting (AGM), including the appointment and the dismissal of the members of the board of directors.

Unfortunately, a lot of the corporate governance literature, including some of the leading textbooks, confuses control with ownership. While the shares of many corporations confer both control and ownership rights, as we shall see this is not always the case. For those corporations for which control does not equate to ownership this has important implications for the types of conflicts of interests that these corporations are likely to suffer from.

The company we shall study is the American company Google Inc. Google Inc.'s 2013 annual report (or what the American Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) calls form 10-K) is available from here. Click on the former link. Don't worry, the link will open in a new window. So you won't navigate away from this blog. If you have managed to get to the correct page, your screen should look like this (N.B. you can click on any of the screen shots included in this blog to magnify them):

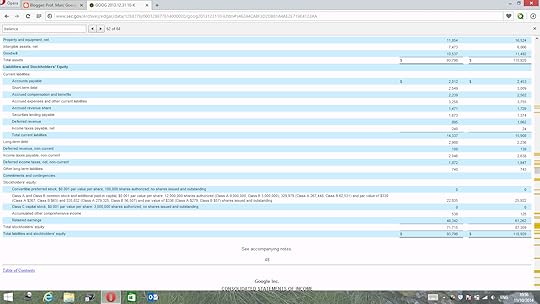

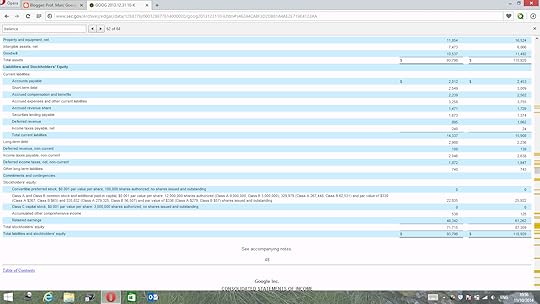

Move to the balance sheet. Towards the bottom of the balance sheet there is information about the stockholders' equity (see screen shot below), i.e. the shares (or stocks) that make up Google Inc.'s equity capital.

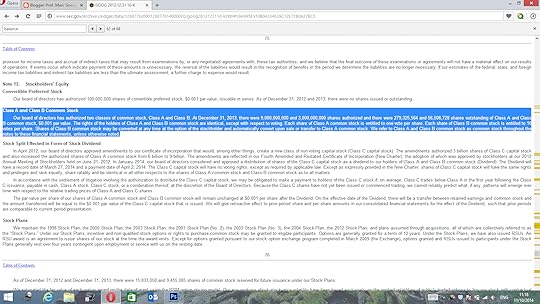

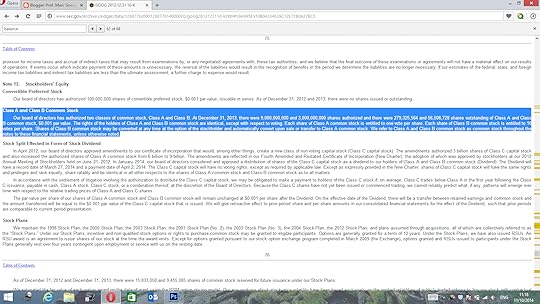

You will notice that Google Inc. has four different types of shares:preferred convertible stock,Class A common stock,Class B common stock, and Class C capital stock.However, while Google Inc. is authorised to issue the first and last type of shares, it does not currently have any such shares outstanding. A bit of a relief really as this will makes things a bit less complicated! We shall now locate the note about the stockholders' equity further down form 10-K. I have highlighted in blue the relevant passage in the note, which is note 12 (see the following screen shot).

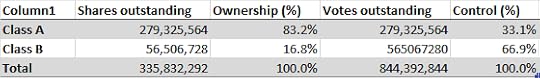

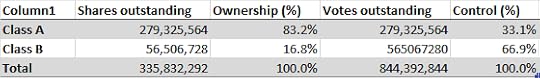

This note provides us with some very important information. Both Class A and Class B stock confer the same rights to their holders, except when it comes to the voting rights. While each Class A stock confers one vote to its holders, each Class B stock confers ten votes! Further, there are 279,325,564 Class A shares, but only 56,506,728 Class B shares outstanding. This means that Class B stock amounts to 16.8% of Google Inc.'s equity but to 66.9% of its total votes outstanding:

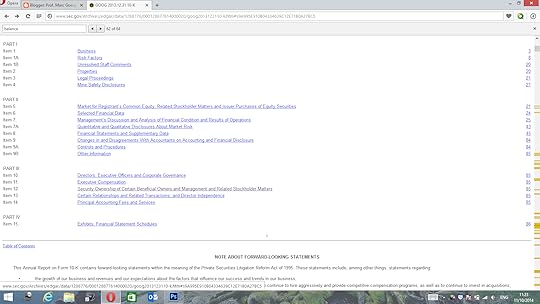

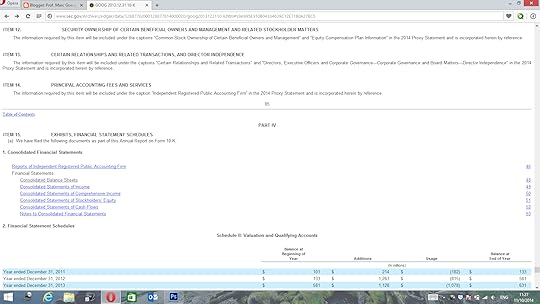

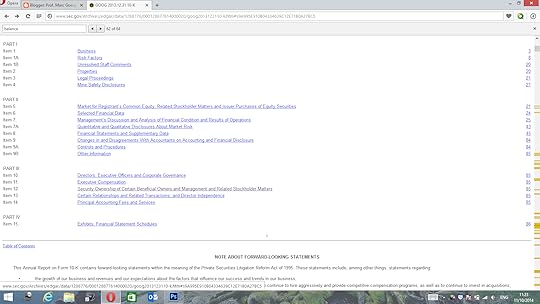

Now we need find out who owns what. Let us go back to the top of the document, more precisely the table of contents (see below).

Item 12 about "Security Ownership of Certain Beneficial Owners and Management and Related Stockholder Matters" is the item we interested in. Click on the item. This should move you to the following place in the document.

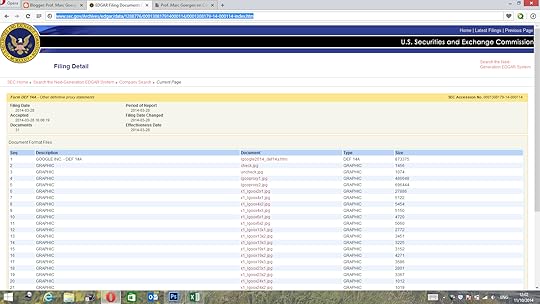

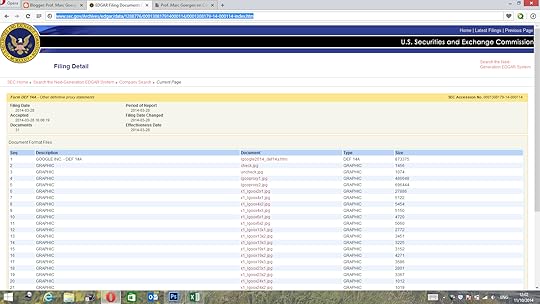

Item 12 refers to another document, the 2014 Proxy Statement. The next step is to locate Google Inc.'s 2014 Proxy Statement, which is also referred to as Form DEF 14A ("DEF" stands for definite or final), on the SEC website. The easiest way to locate it is via the SEC search engine, which can be accessed by clicking here. Enter "Google" into the Company Search Field and press the Search button. Click on CIK 0001288776 next to "GOOGLE INC" in the middle of the list with the search results. You should then see the EDGAR Search Results Screen. Enter "DEF 14A" in the "Filing Type" search field and press the Search button. At the top of the list, you should then see the 2014 Proxy Statement, with a filing date of 28 March 2014. Click on the Documents button next to that filing. If you have done everything correctly, you should arrive at the screen below:

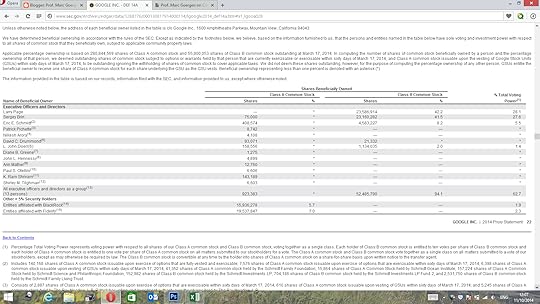

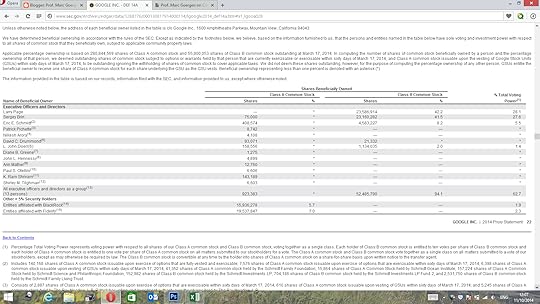

Click on "lgoogle2014_def14a.htm" in the top row of the Document column. Locate the section called "COMMON STOCK OWNERSHIP OF CERTAIN BENEFICIAL OWNERS AND MANAGEMENT" in the proxy statement. Further down the section, you should be able to locate the following table:

You will see that the virtually all of the Class B stock, i.e. 94.1%, is owned by the executive officers (the executives) and the directors (the non-executives). However, they only own 94.1% of 16.8% of the total equity. Hence, while their voting rights amount to 62.7%, their ownership is only 15.8%! The two founders of Google, i.e. Larry Page and Sergey Brin, control 55.7% of the votes while owning only 14.1% of the company!

As a further exercise, try and identify which of the four combinations of ownership and control (i.e. A, B, C or D) applies to Google Inc.(see Chapter 3 of "International Corporate Governance").

Legal disclaimer: This blog reflects my personal opinion and not necessarily that of my employer. Any links to external websites are provided for information only and I am neither responsible nor do I endorse any of the information provided by these websites.

How Larry Page and Sergey Brin manage to control 83% of the votes in Google Inc. with a 14% ownership stake.

Before we can proceed just a reminder what we mean by control and ownership. Ownership is defined as ownership of cash flow rights. Cash flow rights give their holder a pro rata claim to the firm's earnings and a pro rata claim to the firm's assets if the firm is to be liquidated. Control is defined as ownership of voting rights. Voting rights give their holder the right to vote for or against a number of agenda points at the annual general shareholders' meeting (AGM), including the appointment and the dismissal of the members of the board of directors.

Unfortunately, a lot of the corporate governance literature, including some of the leading textbooks, confuses control with ownership. While the shares of many corporations confer both control and ownership rights, as we shall see this is not always the case. For those corporations for which control does not equate to ownership this has important implications for the types of conflicts of interests that these corporations are likely to suffer from.

The company we shall study is the American company Google Inc. Google Inc.'s 2013 annual report (or what the American Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) calls form 10-K) is available from here. Click on the former link. Don't worry, the link will open in a new window. So you won't navigate away from this blog. If you have managed to get to the correct page, your screen should look like this (N.B. you can click on any of the screen shots included in this blog to magnify them):

Move to the balance sheet. Towards the bottom of the balance sheet there is information about the stockholders' equity (see screen shot below), i.e. the shares (or stocks) that make up Google Inc.'s equity capital.

You will notice that Google Inc. has four different types of shares:preferred convertible stock,Class A common stock,Class B common stock, and Class C capital stock.However, while Google Inc. is authorised to issue the first and last type of shares, it does not currently have any such shares outstanding. A bit of a relief really as this will makes things a bit less complicated! We shall now locate the note about the stockholders' equity further down form 10-K. I have highlighted in blue the relevant passage in the note, which is note 12 (see the following screen shot).

This note provides us with some very important information. Both Class A and Class B stock confer the same rights to their holders, except when it comes to the voting rights. While each Class A stock confers one vote to its holders, each Class B stock confers ten votes! Further, there are 279,325,564 Class A shares, but only 56,506,728 Class B shares outstanding. This means that Class B stock amounts to 16.8% of Google Inc.'s equity but to 66.9% of its total votes outstanding:

Now we need find out who owns what. Let us go back to the top of the document, more precisely the table of contents (see below).

Item 12 about "Security Ownership of Certain Beneficial Owners and Management and Related Stockholder Matters" is the item we interested in. Click on the item. This should move you to the following place in the document.

Item 12 refers to another document, the 2014 Proxy Statement. The next step is to locate Google Inc.'s 2014 Proxy Statement, which is also referred to as Form DEF 14A ("DEF" stands for definite or final), on the SEC website. The easiest way to locate it is via the SEC search engine, which can be accessed by clicking here. Enter "Google" into the Company Search Field and press the Search button. Click on CIK 0001288776 next to "GOOGLE INC" in the middle of the list with the search results. You should then see the EDGAR Search Results Screen. Enter "DEF 14A" in the "Filing Type" search field and press the Search button. At the top of the list, you should then see the 2014 Proxy Statement, with a filing date of 28 March 2014. Click on the Documents button next to that filing. If you have done everything correctly, you should arrive at the screen below:

Click on "lgoogle2014_def14a.htm" in the top row of the Document column. Locate the section called "COMMON STOCK OWNERSHIP OF CERTAIN BENEFICIAL OWNERS AND MANAGEMENT" in the proxy statement. Further down the section, you should be able to locate the following table:

You will see that the virtually all of the Class B stock, i.e. 94.1%, is owned by the executive officers (the executives) and the directors (the non-executives). However, they only own 94.1% of 16.8% of the total equity. Hence, while their voting rights amount to 94.1%, their ownership is only 15.8%! The two founders of Google, i.e. Larry Page and Sergey Brin, control 83.7% of the votes while owning only 14.1% of the company!

As a further exercise, try and identify which of the four combinations of ownership and control (i.e. A, B, C or D) applies to Google Inc.(see Chapter 3 of "International Corporate Governance").

Legal disclaimer: This blog reflects my personal opinion and not necessarily that of my employer. Any links to external websites are provided for information only and I am neither responsible nor do I endorse any of the information provided by these websites.

September 15, 2014

Wall Street tries to weed out the wolves while London st...

Wall Street tries to weed out the wolves while London stays sheepish

Wall Street tries to weed out the wolves while London stays sheepish

By Marc Goergen, Cardiff University

When Mathew Martoma, the former portfolio manager of SAC Capital, was sentenced to nine years in prison for insider trading last week, much of the comment was about how harsh the punishment looked. It must have seemed particularly so to traders in the dealing rooms of light-touch London.

In truth, Martoma should take some of the blame. Federal court judge Paul Gardephe justified the length of the sentence by the exceptionally high gains that he had made from this deal, his lack of repentance and his refusal to co-operate with the authorities.

Martoma had been dealing on non-public information he had received from a doctor about clinical trials of a new Alzheimer’s drug. He received the private information on a Sunday in July 2008. The next day, SAC Capital sold its $700m stake in US-based Wyeth Pharmaceuticals and Irish Élan Corporation, the two joint developers of the drug, before the stock prices of the latter two crashed. Martoma’s trade generated roughly $275m for SAC Capital and just above $9m in bonuses for himself. Meanwhile, billionaire Steve Cohen, the only owner of now-defunct SAC Capital, managed to avoid jail and walked off with a fine of $1.2 billion.

RebirthThis was not the first time SAC Capital had been in the spotlight for insider trading. While several traders associated with the fund – such as Michael Steinberg who was sentenced for insider trading of Dell and Nvidia stock – had been convicted of insider trading offences, the prosecutors had never been able to go after Steve Cohen, Mr Big himself.

The Martoma case was different, though, and there was enough evidence for the courts to shut down SAC Capital. Although Cohen had to pay $600m in a settlement with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), in addition to the $1.2 billion fine and the shutting down of SAC Capital, he nevertheless managed to avoid a prison sentence. He is now in charge of

Marc Goergen does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

September 6, 2014

Quiz - How much do you know about corporate governance?

August 9, 2014

International Corporate Governance - Chinese Version

Endorsements on the back cover:

'An excellent textbook which truly stands out. It is better than any book on corporate governance that I have seen', Luc Renneboog, Tilburg University

'Marc Goergen's book on corporate governance is by far the best textbook that has been published on the topic. He has done a wonderful job of covering the topics from a global perspective and I strongly recommend it to all scholars and students with an interest in corporate governance', Franklin Allen, Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania

'An excellent and very comprehensive book. It should become a standard reference on corporate governance', Colin Mayer, Saïd Business School, University of Oxford

Reviews:

James McRitchie's review of the book is available here.

David Hillier lists International Corporate Governance among the best finance textbooks and the best text on corporate governance.

INTERNATIONAL CORPORATE GOVERNANCE - CHINESE VERSION...

The highly acclaimed textbook International Corporate Governance has now been published in a Chinese translation from China Machine Press. The book is available from Amazon China.

May 17, 2014

AMONGST FRIENDS AND FAMILY – HOW SOCIAL AND FAMILY BOARD TIES AFFECT BUSINESSES

The full study was published in the Journal of Corporate Finance and can be found here. A pre-publication version of the same study is available from the SSRN website. See also my blog on the Cadbury Code which refers to above study. Chapter 14 of International Corporate Governance reviews corporate governance issues pertaining to initial public offerings.

Legal disclaimer: This blog reflects my personal opinion and not necessarily that of my employer. Any links to external websites are provided for information only and I am neither responsible nor do I endorse any of the information provided by these websites.

April 19, 2014

COUNTRY TRUST, FIRM TRUST AND THEIR IMPACT ON FIRM FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE

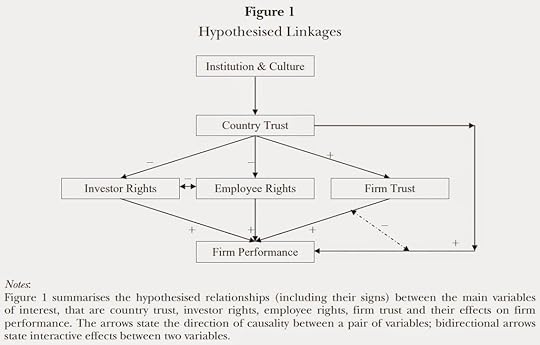

When it comes to what drives country trust, the literature is somewhat less consistent. Broadly speaking however, country trust is negatively affected by income inequality, ethno-linguistic diversity and the importance of hierarchical religions. Contradicting the "trickle-down" wealth effect, this literature finds that income inequality is bad for economic wealth, via the decrease in country trust which in turn hurts economic growth. Ethno-linguistic diversity is normally measured by the probability that two randomly selected persons from a country have different mother tongues. The idea here is that, if people within a country speak (lots of) different languages, they will find it difficult or impossible to communicate with each. The result would be mutual distrust. Hierarchical religions also seem to cause distrust. This goes back to a thesis developed by Robert Putnam, a Harvard University professor of political science. He argues that vertical associations, that is associations with hierarchical structures, engender distrust whereas horizontal associations, that is those whose members are all on a par, create trust. Some religions such as Catholicism are clearcut examples of hierarchical institutions.

However, existing studies on trust and economic performance have neglected the firm level. I conducted a study (click here for the pre-publication version) with colleagues where, in addition to country level trust, we look at the impact of firm level trust on firm financial performance. In order to measure firm level trust, we use survey data from the Cranfield Network (Cranet). We look at five different aspects of firm level trust, based on a total of 73 questions from the Cranet survey. These aspects include (i) staff communication, (ii) profit sharing, (iii) internal promotion, (iv) staff turnover, and (v) training.

We study a total of 2,999 firm-level observations from 19 OECD countries. Apart from country trust and firm trust, we also look at the impact of a country's institutional setting on firm performance. In terms of the institutional setting, we focus on the degree of investor protection and the level of worker rights.

Source: Goergen, M., Chahine, S., Brewster, C. and Wood, G. (2013), Trust, Owner Rights, Employee Rights and Firm Performance. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 40: 589–619. doi: 10.1111/jbfa.12033What do we find? We confirm the positive effect of country trust on performance. However, firm level trust also matters and has a strong and consistently positive effect on firm performance. This suggests that firms operating in countries characterised by weak trust can overcome this institutional weakness by creating their own high-trust environment. In turn, this would improve their financial performance.

Source: Goergen, M., Chahine, S., Brewster, C. and Wood, G. (2013), Trust, Owner Rights, Employee Rights and Firm Performance. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 40: 589–619. doi: 10.1111/jbfa.12033What do we find? We confirm the positive effect of country trust on performance. However, firm level trust also matters and has a strong and consistently positive effect on firm performance. This suggests that firms operating in countries characterised by weak trust can overcome this institutional weakness by creating their own high-trust environment. In turn, this would improve their financial performance.Similar to what I wrote in an earlier blog post, the main lesson here is that companies can and often should go beyond what regulation requires them to do. Within the above context, it is often easier and quicker to improve firm level trust than country level trust. Another important lesson is that corporate governance and investor protection should not be seen in isolation from the rights of important stakeholders, such as employees. Again, this suggests that corporate governance should not be reduced to compliance and "best" practice.

April 5, 2014

CONTRACTUAL CORPORATE GOVERNANCE – OR WHY CORPORATE GOVERNANCE IS NOT JUST ABOUT COMPLIANCE

In 2007, while holding a chair in finance at Sheffield University, I organised a conference on contractual corporate governance with the help of Prof. Luc Renneboog from Tilburg University. We defined contractual corporate governance as

The ways and means by which individual companies can deviate from their national corporate governance standards by increasing (or reducing) the level of protection they offer to their shareholders and other stakeholders.The best papers from the conference were published in a special issue of the Journal of Corporate Finance . This special issue focused on three ways by which firms could deviate from their national standards. These included:cross-listings,cross-border mergers and acquisitions, andreincorporations.A cross-listing consists of a firm being listed on a foreign stock exchange, in addition to its domestic stock exchange. Within that context, Prof. John Coffee advanced the so called bonding hypothesis. According to this hypothesis, firms from countries with weak corporate governance cross-list on a stock market with stricter regulation (typically a US stock market) to commit themselves not to expropriate their (minority) shareholders. Why would firms want to do that? Well, one of the consequences from weak corporate governance is that firms will be charged a higher cost of capital by their providers of finance, including their shareholders. In other words, firms that are perceived to have weak corporate governance (possibly due to weak national law and weak law enforcement) will have to pay a premium to their shareholders, compensating them for the greater risk they incur by investing in such firms. For firms that operate in highly competitive product (or service) markets an above-average cost of capital may effectively be their death sentence. Hence, a way forward would be for such firms to opt voluntarily into a better corporate governance system. This could be achieved via a cross-listing. A study, which I conducted with my colleague Dr Wissam Abdallah and which was published in the special conference issue, finds that firms with large shareholders from countries with relatively weak law are more likely to cross-list on markets with better law. This suggests that these large shareholders make a conscious effort to show their minority shareholders that they are safe from being expropriated.

Another way for a firm to go beyond its national standards would be a cross-border merger & acquisition (M&A). Without going into too much detail, the firm could be the bidder or the target in the cross-border M&A. More importantly, the two papers on cross-border M&As published in the special issue of the Journal of Corporate Finance suggest that the better corporate governance of one of the counter-parties typically spills over to the counter-party with the weaker corporate governance. Hence, alongside cross-listings cross-border M&As seem to be one way for firms to exceed their national standards of corporate governance.

Finally, firms may reincorporate in a country with better corporate governance. However, this is not always the case as the example of the USA suggests. Indeed, the vast majority of US firms that reincorporate in another US federal state do so in Delaware. Delaware is known for favouring managers over shareholders by e.g. offering anti-takeover devices which may shield the former from the disciplinary role of hostile takeovers. Hence, as reincorporations are concerned, the jury is still out there as to whether they will result in a race to the bottom (whereby firms would all move to countries with weaker corporate governance and law) or a race to the top (whereby firms would all move to countries with better corporate governance and more efficient law).

Returning to contractual corporate governance, it is important to realise that for some firms best practice is not good enough and that they may want and need to do better than that. More generally, investors should be very suspicious about firms that follow the herd. Every firm is different and is likely to suffer from particular corporate governance problems and conflicts of interests. Firms can only gain from having a grown-up approach to corporate governance rather than a boiler plate approach. To put it bluntly, good corporate governance is about spelling out one's firm's potential weaknesses and then putting in place mechanisms that mitigate these weaknesses. Let us stop reducing corporate governance to compliance. Indeed, some firms need to do more than just to comply. This also calls for rethinking how corporate governance is taught in business schools.

Note: See also chapter 13 of my book 'International Corporate Governance' which provides an introduction to contractual corporate governance.

Legal disclaimer: This blog reflects my personal opinion and not necessarily that of my employer. Any links to external websites are provided for information only and I am neither responsible nor do I endorse any of the information provided by these websites.

March 29, 2014

CORPORATE GOVERNANCE – MODULE OUTLINE

On completion of the module you should be able to: Evaluate the current state of corporate governance in an international context; describe differences in corporate control and managerial power across the world; assess the potential conflicts of interests that may arise in various corporate governance environments; critically evaluate the effectiveness of the main corporate governance mechanisms and their impact on firm value; explain the potential consequences of weak corporate governance as well as behavioural biases on corporate decision making and firm value; analyse the development of corporate social responsibility. SYLLABUS CONTENTDefining corporate governance and key theoretical modelsCorporate control across the world – Control versus ownership rightsTaxonomies of corporate governance systemsThe disciplining of badly performing managers under different systems of corporate governance Corporate governance regulation in an international contextCorporate governance in emerging marketsBehavioural biases and corporate governanceCorporate social responsibility and socially responsible investment READING Goergen, M. (2012), International Corporate Governance, Harlow: Pearson Education, ISBN 978-0-273-75125-0.

Defining corporate governance and key theoretical modelsGoergen (2012), chapter 1.

Corporate control across the world Control versus ownership rightsGoergen (2012), chapters 2-3.

Taxonomies of corporate governance systemsGoergen (2012), chapter 4.

Incentivising managers and disciplining badly performing managersGoergen (2012), chapter 5.

Corporate governance regulation in an international contextGoergen (2012), chapter 7.

Further resources

An extensive library covering most national and international codes of corporate governance can be found on the website of the European Corporate Governance Institute (ECGI): http://www.ecgi.org/codes/index.php Corporate governance in emerging marketsGoergen (2012), chapter 12.

Behavioural biases and corporate governanceGoergen (2012), chapter 15.

Corporate social responsibility and socially responsible investmentGoergen (2012), chapter 8.

ADDITIONAL MODULE RESOURCES PowerPoint Slides

100 multiple choice questions

End-of-chapter discussion questions and exercises – Instructor’s manual

European Corporate Governance Institute (ECGI)

Andrei Shleifer’s dataset website with investor protection and anti-director rights indices

Social Sciences Research Network

NOTEThe above module outline is just one of the many paths through Goergen (2012). There are others, some of which are depicted in the diagram below.