Marc Goergen's Blog, page 5

July 16, 2017

How Far That Little Candle Throws His Beams! An Interview With Mats Isaksson

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The authors received financial support for the research from the Centre for Business in Society, Faculty of Business and Law, Coventry University, United KigdomSource: Merendino, A. and. M. Goergen (2017), "How Far that Little Candle Throws His Beams! An Interview with Mats Isaksson", Journal of Management Inquiry, CC BY 4.0 licence.

CC BY 4.0

March 20, 2017

Corporate Governance. A Global Perspective.

The table of contents (subject to change) of version two is as follows:

Part I – Introduction to Corporate Governance

Defining corporate governance and key theoretical modelsCorporate control across the worldControl versus ownership rightsPart II – Macro Corporate Governance

Taxonomies of corporate governance systemsCorporate governance, types of financial systems and economic growthCorporate governance regulation in an international contextPart III – Improving Corporate Governance

Boards of directorsIncentivising managers and the disciplining of badly performing managersCorporate governance in emerging marketsContractual corporate governanceCorporate governance in initial public offeringsBehavioural biases and corporate governancePart IV – Corporate Governance and Stakeholders

Corporate social responsibility and socially responsible investmentDebtholdersEmployee rights and voice across corporate governance systemsThe role of gatekeepers in corporate governancePart V – Conclusions

Learning from diversity and future challenges for corporate governanceGlossary

Index

December 3, 2016

The Impact of Board Gender Composition on Dividend Payouts

This post was originally posted on the Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance and Financial Regulation.Legal disclaimer: This blog reflects my personal opinion and not necessarily that of my employer. Any links to external websites are provided for information only and I am neither responsible nor do I endorse any of the information provided by these websites.

December 5, 2015

International Corporate Governance – Translations

The original English version was published by Pearson Education and is available in print as well as via Kindle and CourseSmart.

Endorsements on the back cover:

'An excellent textbook which truly stands out. It is better than any book on corporate governance that I have seen', Luc Renneboog, Tilburg University

'Marc Goergen's book on corporate governance is by far the best textbook that has been published on the topic. He has done a wonderful job of covering the topics from a global perspective and I strongly recommend it to all scholars and students with an interest in corporate governance', Franklin Allen, Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania

'An excellent and very comprehensive book. It should become a standard reference on corporate governance', Colin Mayer, Saïd Business School, University of Oxford

Reviews:

James McRitchie's review of the book is available here.

David Hillier lists International Corporate Governance among the best finance textbooks and the best text on corporate governance.

October 24, 2015

The relationship between the CEO and the chairman of the board of directors

In a new study I have published in the Journal of Corporate Finance (the pre-publication version can be obtained from here) and which is co-authored with Peter Limbach and Meik Scholz from the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, we find that the age difference between the CEO and the chairman of the board of directors also matters. We argue that greater age dissimilarity between the CEO and the chair is likely to increase cognitive conflict between the two, which likely results in more scrutinising by the chair of the decisions proposed by the CEO. Such cognitive conflict is likely to be greatest when there is a generational gap, i.e. 20 years or more, between the two. Indeed, individuals from different generations have had different experiences and therefore tend to hold different attitudes and opinions.

In line with the above arguments, we find that firms with greater age dissimilarity between the CEO and the chairman tend to hold significantly more board meetings, likely reflecting the greater monitoring intensity by the board of directors. Importantly, a greater age difference between the CEO and the chair creates value in firms with a greater need for monitoring, such as firms without a large shareholder and those in more traditional industries with few intangible assets. In contrast, it destroys value in firms that require advice rather than monitoring from the board.

Again, this suggests that it is naive at best to consider that the effectiveness of the board of directors can be reduced to board independence. Relations within the boardroom are much more complex than the balance between executive and non-executive directors would suggest.

Legal disclaimer: This blog reflects my personal opinion and not necessarily that of my employer. Any links to external websites are provided for information only and I am neither responsible nor do I endorse any of the information provided by these websites.

July 13, 2015

Why we need to rethink the UK's approach to corporate governance regulation

March 20, 2015

Approach adopted by "International Corporate Governance"

The book is organised into 5 different parts. Part I introduces corporate governance, reviews the theoretical body and develops the main concepts of corporate governance that are used across the book. Part II focuses on international corporate governance; including taxonomies of corporate governance systems; how to incentivise managers and how to discipline those that perform badly; the link between corporate governance, types of financial systems and economic growth; and corporate governance regulation. Part III analyses the role of various stakeholders in corporate governance. These stakeholders include debtholders, such as banks, employees and gatekeepers. This part also studies the role of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and socially responsible investments (SRIs). Part IV looks at possible ways of improving corporate governance. This part looks at corporate governance in emerging markets, contractual corporate governance, corporate governance in initial public offerings, and behavioural biases that affect managers' decision making. Finally, Part V of the book concludes.

An extensive glossary at the end of the book enables the reader to revisit quickly the concepts and technical terms used throughout the book. Complimentary teaching support material - including a test bank with 100 multiple choice questions, an instructor's manual and a complete set of PowerPoint slides - is available from here.

Reviews of the book include James McRitchie's review at corpgov.net and Prof. David Hillier's review.

The book is also now available in a Chinese translation from China Machine Press. It will soon be available in a Greek translation from Diplographia.

Endorsements on the back cover:

'An excellent textbook which truly stands out. It is better than any book on corporate governance that I have seen', Luc Renneboog, Tilburg University

'Marc Goergen's book on corporate governance is by far the best textbook that has been published on the topic. He has done a wonderful job of covering the topics from a global perspective and I strongly recommend it to all scholars and students with an interest in corporate governance', Franklin Allen, Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania

'An excellent and very comprehensive book. It should become a standard reference on corporate governance', Colin Mayer, Saïd Business School, University of Oxford

Legal disclaimer: This blog reflects my personal opinion and not necessarily that of my employer. Any links to external websites are provided for information only and I am neither responsible nor do I endorse any of the information provided by these websites.

March 14, 2015

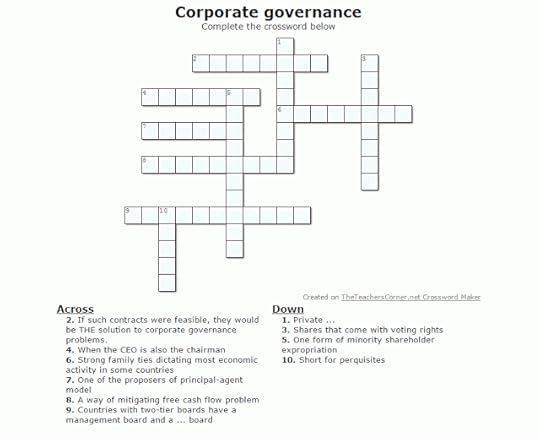

Corporate governance crossword

December 20, 2014

The private equity deals that fail to justify 'fast ...

The private equity deals that fail to justify 'fast buck' strategies

The private equity deals that fail to justify 'fast buck' strategies By Marc Goergen, Cardiff University; Geoffrey Wood, University of Warwick, and Noel O'Sullivan, Loughborough University

There is an ongoing and very heated debate between the unconditional supporters of private equity and their opponents. It’s not hard to see why. On the surface, these investors can often buy fragile companies, load on debt to fund strategic change and sack workers in a bid for efficiency. It can look ruthless, but the industry claims it simply works.

The British Private Equity & Venture Capital Association (BVCA), preach what they deem to be the undeniable benefits of private equity. For example, the trade lobby group wrote in 2010 that:

Private equity investment has been demonstrated to contribute significantly to companies’ growth. Private equity backed companies outperform leading UK businesses.

In contrast, Ed Miliband in his speech at the 2011 annual Labour Party conference accused private equity houses of “stripping assets for a quick buck and … [failing to represent] the values of British business.”

Horses for coursesTo date, studies of private equity acquisitions of firms listed on the stock exchange disagree as to the effects on employment. A major issue is that the studies typically conflate very different forms of private equity acquisitions which are likely to vary significantly in terms of their impact. At the most extreme, some of this research fails to distinguish between private equity and venture capital, which typically provides equity financing to early-stage firms that are not yet listed on the stock market.

Such firms typically face severe difficulty raising cash to fund their growth. Banks are unwilling to lend them money given their high levels of risk and the firms cannot as yet tap into stock-market equity financing (and Dragon’s Den can’t or won’t fill the gap). For such firms, venture capitalists not only provide the much needed money, but also frequently provide strategic and management advice, which can be crucial for the survival of the firm. In short, there is very little doubt about the benefits, including those relating to employment, of venture capital financing.

In contrast, private equity typically targets mature firms that are already listed on the stock market and that offer well-established products or services. In the process of the private equity acquisition, the firm’s existing shareholders are bought out – often with the use of substantial amounts of debt, the firm is taken off the stock market (it is “taken private”) and then undergoes major long-term strategic and organisational changes. Such changes would not normally have been possible had the firm kept its stock market listing given the focus on the short term of most stock market investors.

Money, money, moneyIs is important to realise that there are three main forms of private equity acquisitions which involve very different stakeholders and which are therefore likely to have very different effects on employment.

The most frequent form of private equity acquisition is a management buy-out or MBO. These involve management of a company taking the firm private, with the help of private equity houses which provide the cash. However, given that the existing management stays in place and carries on running the firm, the employment effects of MBOs are typically very positive or neutral at worst.

However, the other two main forms of private equity acquisitions – management buy-ins (MBIs) and institutional buy-outs (IBOs) – result in a change in the management. In the case of less-frequent MBIs, a new management team buys out the existing shareholders and takes the firm private and the input of private equity houses is typically limited to the financing. In the case of IBOs, the private equity house not only provides the financing, but also the management team. You can happily make the case for the positive employment effects of MBOs. The evidence on MBIs and IBOs, however, is much more mixed (see Goergen et al. 2011 for an overview).

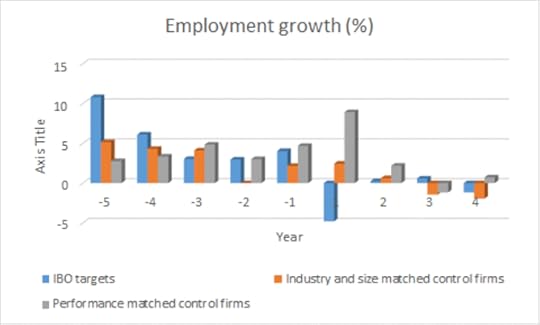

A new study that we’ve published in the European Economic Review, sheds new light on the employment effects of UK IBOs. The study is based on 106 IBO acquisitions of UK listed firms between 1997 and 2006 (during the same period there were 139 MBOs and six MBIs). The sample included well-known companies such as Churchill China (check the bottom of your restaurant crockery), Fox’s biscuits and Goodfella’s Pizza maker Northern Foods and the high street department store Debenhams.

We compared the IBO targets with two control samples of firms which were not acquired. The first sample was matched by size and industry while the second was matched by pre-acquisition financial performance.

The IBO firms were followed for up to six years before and four years after the acquisition. The findings are stark reading. The most important thing is that there is a significant decrease in employment in the year following the acquisition in the target firms of IBOs, but not in two samples of control firms that we also had. And this drop in employment is combined with a drop in wages below the market rates for the target firms.

The IBO companies’ median employment growth was 11% five years before acquisition, falling down to –4.80% the year after the deal (see figure 1). Figures on salary suggest a similar trend with IBO companies seeing a salary reduction from a mean of £29,460 before the IBO to £28,520 following it.

Stability pactThose cynical about the industry might not be surprised by the above, but there is more. Importantly, despite what could be perceived as a much needed cull of the work force, the target firms do not experience an improvement in their profitability and productivity following the acquisition. The suggestion is clear: the increased insecurity inherent in the shedding of jobs and the downward pressure on wages outweighs any of the potential benefits from a change in management brought about by an institutional buy-out.

While this new study uncovers negative effects on employment of a particular type of private equity acquisitions – so called institutional buy-outs (IBOs) – it does not imply that all private equity acquisitions are bad for employment. What the results do suggest is that the debate on the effects of private equity acquisitions needs to be much more nuanced.

Importantly, it needs to distinguish between those types of private equity acquisitions that have undeniable positive benefits for employment – as well as the survival and competitiveness of UK businesses – and those that are likely to be mostly detrimental.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

October 25, 2014

Ooh Danone – More than just yogurt

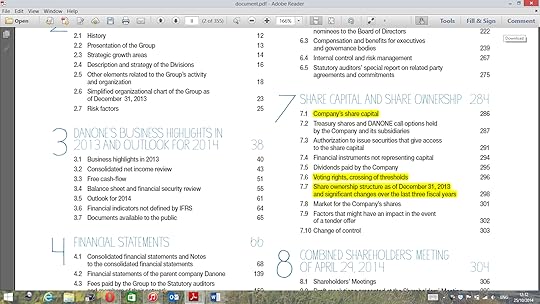

Danone S.A.'s most recent company report (or 'registration document') is available from here. You might need to click on '2013' to obtain the most recent available company report at the time of writing this blog.

This might be obvious, but it is always a good idea to start by having a look at the table of contents. This should give you a fairly good idea where to find important information on control and ownership. Below I have highlighted in yellow what should be important sections in the company report (click on the picture to make it larger):

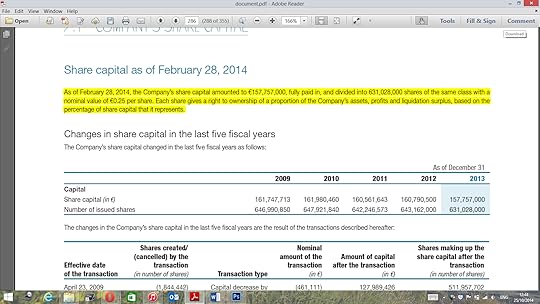

Let us start with Section 7.1 "Company's Share Capital". First of all, Danone S.A. has only one class of shares:

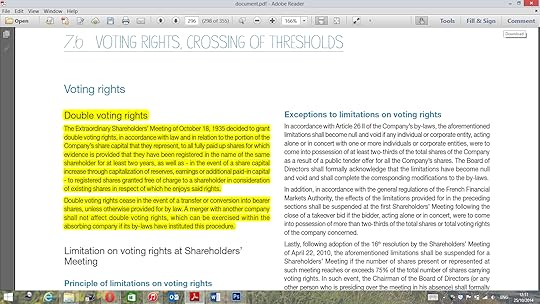

So, it is different from Google Inc. which has two classes of shares. But hey, as we are going to see this does not mean that this example is any easier than the previous one on Google Inc.! Let us now move to Section 7.6 "Voting Rights, Crossing of Thresholds". This is where things get interesting:

Danone S.A., as a lot of other French companies, confers multiple voting rights (double voting rights to be specific) to long-term shareholders who have registered their shares with the company and have owned the shares for at least two years. However, things are more complicated than that:

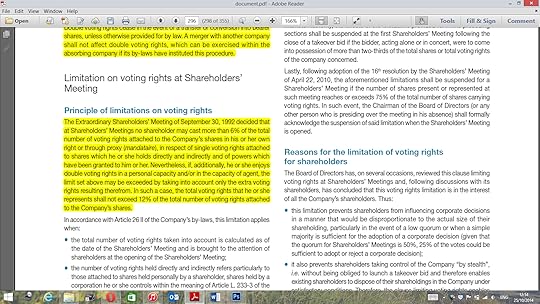

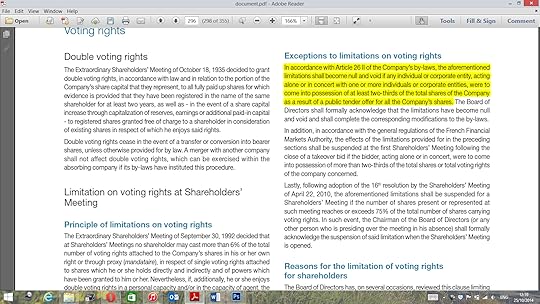

Danone S.A. also has a voting cap or limit of 6%. However, for shareholders who have double votes (see above) the limit is 12%. Nevertheless, this voting cap will become void if a single shareholder acquires more than two thirds of the company's shares as a result of a public tender offer:

There is more interesting information (such as the reasons for the voting cap) on this same page, but for the sake of brevity I shall skip it. Let us now have a look at Section 7.7 on the share ownership structure:

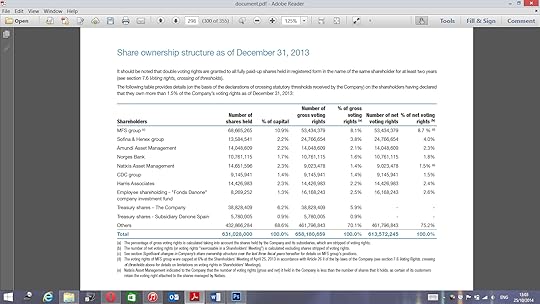

Danone S.A. does not have a majority shareholder or a shareholder with a blocking minority. This is typically the case of companies with a voting cap in place. Similar to Google Inc., there are differences between the percentages of votes and the percentages of cash flow rights individual shareholders hold. Some shareholders, such as Sofina & Henex group and the Danone employee fund, hold more votes than cash flow rights. Others, such as MFS group, hold fewer votes than cash flow rights.

Returning to Chapter 3 of "International Corporate Governance", Danone S.A. would fit under combination C given its voting cap. However, it would also fit under combination D given the provision of conferring double voting rights in its articles of association. Nevertheless, the voting cap is the strongest of the two provisions. Hence, Danone S.A. does fit under combination C as control clearly lies with the management rather than a large shareholder. This means that the main potential conflict of interests for this company is between the management and the shareholders.

Legal disclaimer: This blog reflects my personal opinion and not necessarily that of my employer. Any links to external websites are provided for information only and I am neither responsible nor do I endorse any of the information provided by these websites.